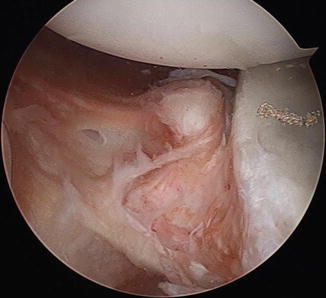

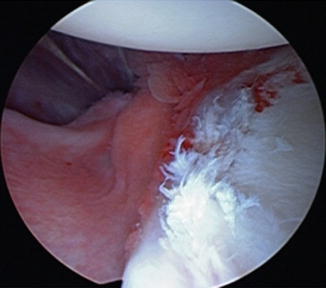

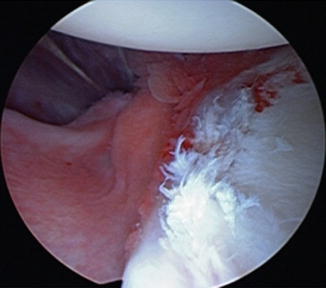

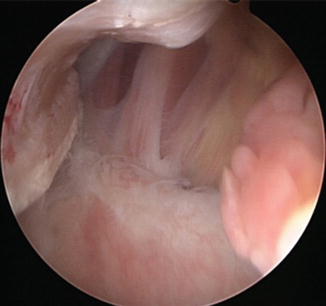

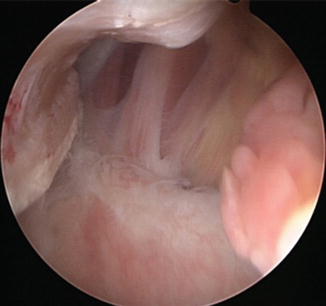

Fig. 13.1

Bankart lesion. The Bankart lesion is the avulsion of the anterior labroligamentous structures from the glenoid rim and the most common pathologic lesion in the traumatic anterior glenohumeral instability. The anterior labrum is disrupted from the glenoid along with disrupted periosteum of the scapular neck and it typically lies anterior to the glenoid

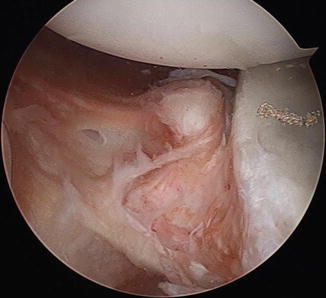

ALPSA, Anterior Labroligamentous Periosteal Sleeve Avulsion, is first described by Neviaser in 1993 [2]. The torn labroligamentous structures are displaced and healed on the medial surface of the anterior glenoid neck (Fig. 13.2). The ALPSA lesion is often found in shoulders with recurrent dislocation [3]. Arthroscopically, it is difficult to identify from the standard posterior portals and often the lesion is not evident even from the anterior portal. When the ALPSA lesion contains a small bony fragment, the lesion is strongly healed to the glenoid neck and often difficult to mobilize during the arthroscopic procedure. ALPSA lesions would be repaired by elevating the labroligamentous complex of the scapular neck and bringing it back to the anatomic position on the glenoid face.

Fig. 13.2

ALPSA lesion. The torn labroligamentous structures are displaced and healed on the medial surface of the anterior glenoid neck

The anterior labral failure, either as the Bankart or ALPSA lesion, can be limited at the anterior glenoid area (Limited Bankart lesion) or it can be extended to the inferior and posterior area, which is coined as an extended Bankart lesion (Fig. 13.3).

Fig. 13.3

Extended Bankart lesion. The anterior labral tear can be extended to the inferior and posterior area of the glenoid

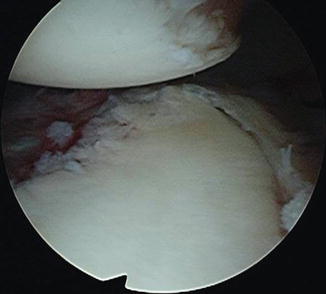

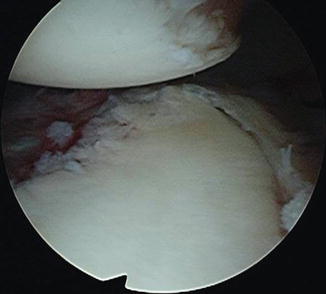

GLAD, Glenolabral Articular Disruption, is also described by Neviaser in 1993 [4]. The GLAD lesion is disruption of articular cartilage from the anterior inferior glenoid surface either as a flap tear or cartilage loss and is caused by a forced adduction injury to the shoulder from an abducted and external rotated position (Fig. 13.4a, b).

Fig. 13.4

GLAD lesion. The GLAD lesion is disruption of articular cartilage from the anterior inferior glenoid surface: (a) flap tear (courtesy of Dr Richard Page, Melbourne Australia); (b) cartilage loss

Bony Bankart lesion occurs with a significant injury, which causes fracture of the anterior inferior glenoid margin in varying sizes. The bony Bankart lesion is very common. Sugaya et al. evaluated the morphology of the glenoid rim and 90 % of the shoulder with traumatic anterior instability showed bony deficiency as a fragment type in 50 % and erosion type in 40 % [5]. The bony Bankart lesion is different from the glenoid erosion. The erosion of the anterior glenoid without bony fragment jeopardizes the stability of the glenohumeral joint even after Bankart repair. The glenoid defect greater than 21 % of the glenoid length or 25 % of the glenoid width requires reconstruction of the glenoid concavity [6].

HAGL, Humeral Avulsion of Glenohumeral Ligament, is detachment of the glenohumeral ligament from the humeral attachment and first described by Bach in 1988 [7]. Later in 1995, Wolf et al. coined the name “HAGL” and the incidence being 1–9 % of the shoulders with anterior glenohumeral instability [8]. The HAGL lesion has clinical significance in planning the type operative procedures. A small HAGL lesion can be managed by arthroscopic side-to-side repair while a large defect may require open surgical repair (Fig. 13.5).

Fig. 13.5

HAGL lesion. HAGL, Humeral Avulsion of Glenohumeral Ligament, is detachment of the glenohumeral ligament from the humeral attachment

Posterior HAGL lesion is a typical finding in shoulders with traumatic posterior instability. We noted that the posterior HAGL lesion is also found in shoulders with traumatic anterior instability. The glenohumeral ligament is avulsed from the posterior humeral attachment. It closely lies in the area of the Hill–Sachs lesion. The posterior HAGL lesion is associated with a large Hill–Sachs lesion (Fig. 13.6).

Fig. 13.6

Posterior HAGL. The glenohumeral ligament is avulsed from the posterior humeral attachment

Capsular lesion is not uncommon in shoulder with anterior glenohumeral instability. It is more common in elderly patients with recurrent dislocation in our experience. It can be an isolated entity. However, the capsular lesion is commonly associated with other pathology such as a Bankart or ALPSA lesion. The clinical significance of the capsular lesion is that the lesion is frequently masked by a thin layer of the fibrous scar tissue.

Bipolar lesion is a combination of any pathoanatomic lesion of the anterior instability.

A common form in ipsilateral bipolar lesion is a combination of Bankart lesion and HAGL or capsular lesion (Video 13.1). The contralateral bipolar lesion is the combined lesion of Bankart and posterior HAGL lesion (Video 13.2). We observed that the bipolar lesion is more common in patients over 30 years in age who have recurrent dislocation.

Hill–Sachs lesion is a bony defect in the posterolateral humeral head and is an impaction injury to the anterior glenoid rim. The incidence is more common in recurrent instability and greater than 20–25 % of the humeral head may develop clinical instability [9, 10]. During arthroscopic surgery, the arm is elevated to bring the shoulder in abduction and external rotation. In this position, if the Hill–Sachs lesion engages with the anterior rim of the glenoid, it is assessed as an engaging Hill–Sachs lesion [11, 12]. Glenoid tract is a zone of contact of the humeral head to the glenoid in the arm position of abduction and external rotation. When the Hill–Sachs lesion remains within the glenoid tract, the humeral head defect is in the risk of engagement and instability [13]. The extent of the Hill–Sachs lesion should be considered in association with the glenoid bone loss. With a small Hill–Sachs defect, a larger degree of glenoid bone loss will increase the risk of recurrent instability.

Rotator cuff tear in the recurrent anterior instability is usually partial-thickness tear of the articular surface of the tendon. However, in elderly patients with significant traumatic dislocation, full-thickness tears of entire supraspinatus and infraspinatus can develop anterior dislocation with or without Bankart lesion.

13.3 Pathoanatomy of Posterior and Multidirectional Instability

Posterior or multidirectional instability occurs usually by atraumatic or repetitive microtraumatic origin. There has been no universal agreement in the classification, terminology, and treatment options. The clinical presentation of the atraumatic instability is not as clear as traumatic anterior instability and many of patients with posterior instability are easily overlooked or treated under other diagnosis. Recent advances in the concept of the posterior instability have provided us reasonable insight into the pathology, pathogenesis, diagnostic examinations, and treatment options. The posterior instability very often presents as bidirectional posteroinferior instability, which has various degrees of inferior component of instability. Also the posterior instability is overlapping with the multidirectional instability in its diagnosis, clinical presentation, and management.

13.3.1 Pathogenesis

Several anatomic structures have been implicated including bony and soft tissue abnormalities. Bony abnormalities include increased humeral retroversion, glenoid retroversion, and glenoid hypoplasia. Although, several studies on the glenoid version have been focused on the bony glenoid measured, the stability of glenohumeral joint is an integral function of both bone and soft tissue stabilizer. Lazarus et al. showed a 65 % decrease in mechanical stability ratio and an 80 % reduction in the height of the glenoid associated with the creation of an anteroinferior chondrolabral defect [14]. Accordingly, the measurement of the glenoid version can be more ideal when the articular cartilage and labrum are considered as a whole. Soft tissue abnormality of the atraumatic instability has been an excessive capsular laxity. However, increased capsular ligamentous laxity alone cannot entirely explain the whole pathogenesis of the atraumatic instability, which often occurs in the mid-range of motion where normally the capsular ligaments become loose.

Kim et al. emphasized that loss of chondrolabral containment is a consistent finding in shoulders with atraumatic posteroinferior instability and is principally due to the loss of posterior labral height [15]. Kim et al. suggest that the loss of chondrolabral containment is a result of cumulative microtrauma to the posteroinferior glenoid labrum which initially has normal height and undergoes gradual change to retroversion by the rim-loading mechanism [15, 16]. With the loss of chondrolabral containment, the static restraint loses its function and the dynamic stabilizer of the shoulder becomes less effective in maintaining concavity compression of the glenohumeral joint. Bradley et al. similarly measured the posterior inferior chondrolabral version and bony glenoid version for each MR at the inferior one third of the glenoid rim [17]. In this study, there was increased bony and chondrolabral retroversion in the symptomatic group, which suggests that loss of anatomical containment predisposes to atraumatic instability (Video 13.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree