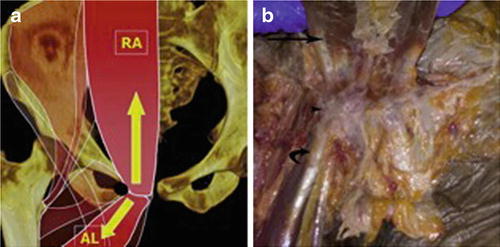

Fig. 1

Diagram of the pubic symphysis demonstrates the midline fibrocartilage pubic disk in red and the anteroinferior arcuate ligament in green (Reprinted from [17] with permission from Elsevier)

The pubic symphysis acts as a fulcrum for forces generated at the anterior pelvis. Musculoaponeurotic plate attachments at the pubic symphysis are important for core stability, and coordinated contraction of the muscles that directly attach to the fulcrum produces a slight anterior tilt of the pelvis. The abdominal muscle attachments include the rectus abdominis and internal oblique, external oblique, and transversus abdominis. The medial thigh compartment attachments include the pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, and gracilis. Functionally, the most important attachments for anterior pelvis stabilization are where the rectus abdominis and the three adductor muscles join to the fibrocartilage plate of the pubic symphysis [16, 18, 19]. The rectus abdominis attaches to the anterior and anteroinferior aspects of the pubic symphysis. The origin of the pectineus and adductors is confluent with the rectus insertion and is defined as the rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis [19].

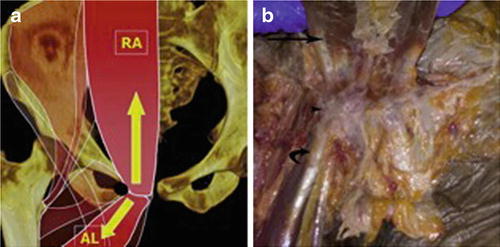

During core rotation and extension, the rectus abdominis and the adductor longus act as antagonists (Fig. 2). The rectus elevates the pelvis, while the adductor depresses it. Injuring one of the components tends to cause abnormal biomechanical forces on opposing muscles and tendons leading to further injury at the aponeurosis and the tenoperiosteal attachments [20]. Detachment of the aponeurosis itself can lead to instability of the pubic symphysis, as can injury to the arcuate or anterior pubic ligaments. Performing activities such as running with an unstable pubic symphysis can lead to detachment of the fibrocartilage plate from the periosteum of the pubis, exacerbating the instability and increasing shearing forces. This may cause an increased stress reaction in the bone and can ultimately lead to fluid crossing the cortex, cyst formation, and symphyseal arthritis [7, 11–13, 17, 21].

Fig. 2

(a) Diagram of the opposing forces of the rectus abdominis (RA) and adductor longus (AL) at the pubic tubercle. The rectus abdominis creates superoposterior tension, whereas the adductor longus creates inferoanterior tension. Disruption of either leads to altered biomechanics. The black circle represents the superficial inguinal ring. (b) Gross specimen demonstrates the rectus abdominis (arrow), the adductor longus (curved arrow), and the pubic tubercle attachment of the rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis (arrowhead) (Reprinted from [17] with permission from Elsevier)

Differences in anatomy of males and females exist due to demands of childbirth on the female anatomy. The female pelvis is a more stable pelvis in that it has fewer shifts in forces and has a relatively wider subpubic angle leading to a different distribution of forces. These forces are likely protective with regard to the development of core injuries in women [22]. The fibrocartilaginous disk and the inner dimensions are also wider in women. The symphysis has 2–3 mm more mobility in women as well, which can increase by up to 10 mm during pregnancy [16].

Patient Presentation

Groin injuries are most common in athletes who participate in sports that require repetitive twisting, pivoting, cutting motions, and frequent acceleration and deceleration. Ice hockey, soccer, and rugby have a particularly high incidence [1–5]. Initial presentation of osteitis pubis typically includes gradual onset of pain over the medial and anterior groin. In some cases pain is present directly over the pubic symphysis, which may be tender to palpation. Other times, tenderness may be palpated over the superior pubic rami, and pain may be felt in the adductor musculature, lower abdominal muscles, perineal region, inguinal region, or scrotum. This pain can progress to the point where the patient is unable to participate in sports. Pain is usually aggravated by athletic activity, particularly with cutting, twisting, and kicking activities as well as with resisted hip adduction or flexion and eccentric loads to the rectum abdominis [1, 2, 15, 23, 24].

It is important to consider the differential diagnosis of osteitis pubis given it shares many of its symptoms with other groin injuries. These include other musculoskeletal etiologies of groin pain such as athletic pubalgia, adductor strain, stress fracture, inguinal hernia, intra-articular hip pathology, femoroacetabular impingement, iliopsoas injury, and abnormality of the lower lumbar spine.

Perhaps the most important differential diagnosis is osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis, which presents in a similar fashion as osteitis pubis and has been reported in the literature to spontaneously occur in athletes [6, 25, 26]. Osteomyelitis can be differentiated based on the acute, atraumatic onset of symptoms that mimic osteitis pubis, along with signs of systemic signs of infection, such as fever, or elevated markers of inflammation such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and leukocytosis [25, 26]. It is important to differentiate the two because the treatments for the two conditions radically differ.

Other atraumatic acute onset groin pains that must be ruled out include testicular torsion, cystitis, appendicitis, nephrolithiasis, and other intra-abdominal and pelvic non-musculoskeletal conditions.

Physical Exam

After a thorough history, a comprehensive physical examination is required to evaluate a patient with groin pain. The physical exam can help with the diagnosis as well as which particular type or sequence of diagnostic imaging to obtain.

Assessment for osteitis pubis should begin with palpation of the pubic symphysis and pubic rami, insertion of the rectus abdominis, adductor origin, external and internal obliques, transversus abdominis, pectineus, gracilis, and inguinal ring for areas of tenderness. Exam findings for osteitis pubis frequently overlap with athletic pubalgia and include tenderness of the pubic symphysis (67 %), adductor origin tenderness (59 %), pain with adductor squeeze test (96 %), and apprehension throughout hip range of motion, particularly with internal rotation. Pain can also be elicited by hip flexion or eccentric loading of the rectus abdominis and with resisted adduction [1, 2, 27–29]. More severe cases may present with a typical “waddling” gait pattern [23].

It is important to rule out intra-articular hip pathology with a thorough physical exam of the hip including hip range of motion (flexion, extension, adduction, and abduction), internal and external rotation, and any provocative testing, i.e., to assess for femoroacetabular impingement with the anterior impingement test (flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) which can suggest intra-articular pathology [30]. Palpation of the insertion of the gluteus medius and minimus, short external rotators, and trochanteric bursa should be performed as well, and a lower extremity neurologic exam and straight leg raise may be useful for ruling out lumbar spine pathology.

Imaging

Radiographic Analysis

Plain radiographs obtained for athletes presenting with groin pain are essential for proper diagnosis. They should be evaluated for osteoarthritis, femoroacetabular impingement, dysplasia, fracture, apophyseal avulsion, and osteitis pubis. The series should include an appropriately oriented weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, a Dunn lateral, and a false profile view [32, 33].

The AP view should be used to evaluate for a crossover sign (cephalad acetabular retroversion), the center edge angle of Wiberg (dysplasia and lateral overcoverage), the acetabular index (dysplasia), the joint space (arthritis), and the pubic symphysis. The Dunn lateral should be used to evaluate the alpha angle for any decreased head- neck offset (cam), pincer trough, or synovial herniation pits. The false profile should be used to evaluate for anterior overcoverage or dysplasia, for anterior center edge angle (dysplasia), for anterior and posterior joint space, and for the morphology of the anteroinferior iliac spine.

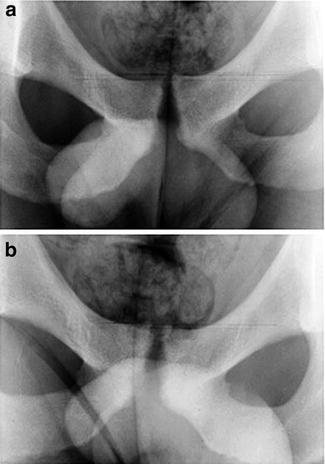

Some authors suggest the use of a “flamingo view,” which is a one-legged AP view of the symphysis used to evaluate for pubic instability. Vertical shift of greater than 2 mm or widening greater than 7 mm indicates instability (Figs. 3 and 4) [4, 28].

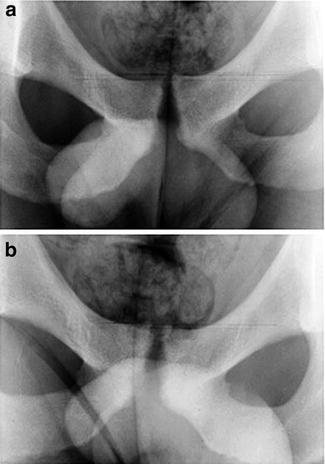

Fig. 3

Standing AP plain film of the pelvis illustrating the classic radiographic features of osteitis pubis: sclerosis, cystic change, and rarefaction of the medial portions of the pubic rami. Reprinted from [28] with permission from Elsevier

Fig. 4

Vertical symphyseal instability demonstrated by AP flamingo view radiographs. (a) Patient standing on left leg. (b) Patient standing on right leg. Reprinted from [28] with permission from Elsevier

Osteitis pubis appears normal in acute cases, but in chronic cases (>6 months), radiographs show cystic changes, sclerosis, fragmentation, widening, or narrowing of the symphysis, and one-legged stance films may suggest instability (Figs. 3 and 4) [13, 31]. These changes need to be correlated with the patient’s symptoms as similar findings can be seen in asymptomatic athletes or athletes with different pathologies [7]. One recent study evaluating radiographic predictors of groin pain found that radiographic evidence osteitis pubis (sclerosis, lytic changes, and cystic changes) was symptomatic only 64.2 % of the time, and it was not independently predictive of groin/hip pain [34].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI has become the diagnostic modality of choice when advanced imaging is required. It has excellent visualization of soft-tissue abnormalities as well as bone marrow changes, and it can help diagnose core injuries of the abdominal musculature and throughout the pelvis region [6]. When patients present with anterior pelvic pain with concern of groin pathology outside of the hip joint, the MRI study should include dedicated high-resolution imaging of the pubic symphysis and its musculotendinous attachments, as well as a large field view of the entire pelvis, to help exclude other pathologies that can mimic osteitis pubis [17, 21].

Osteitis pubic has acute and chronic forms that can manifest differently on imaging. Acute osteitis pubis on MRI shows bone marrow edema involving the subchondral bone spanning the entire symphysis. The edema is usually bilateral but often asymmetric with more advanced edema involving the symptomatic side (Fig. 5a) [13, 20, 31]. This is best seen using STIR (short tau inversion recovery) or T2 fat-suppression sequences in the coronal plane [36]. The increased signal may be noted over a broad area of the parasymphyseal bone. It can also occur as a hyperintense line paralleling the subchondral bone plate of the pubis that has been found in the majority of symptomatic athletes and may prove to be more clinically relevant than bone marrow edema alone, which can be seen in asymptomatic athletes [27]. This should be differentiated from focal marrow edema at the pubic tubercles, which can be seen with avulsive injuries of the rectus abdominis-adductor aponeurosis.

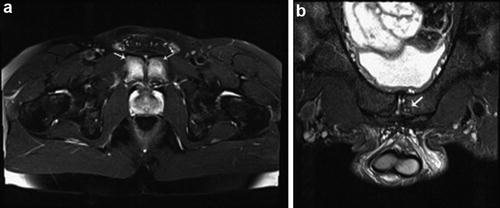

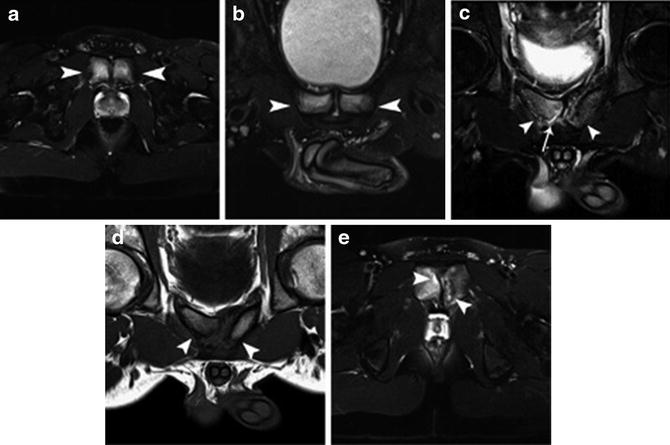

Fig. 5

(a) Bone marrow edema spanning the subchondral region of the pubic symphysis anterior to posterior on an axial FSE fat-saturated T2-weighted image (arrows) typical for severe osteitis pubis. (b) Coronal oblique FSE fat-saturated T2-weighted image shows chronic osteitis pubis with osseous productive change and subchondral cyst formation (arrow) (Reprinted from [35] with permission from Elsevier)

Severe osteitis pubis can show extensive subchondral marrow edema with articular erosion similar to distal clavicular osteolysis at the acromioclavicular joint. With theses severe lesions, healing potential is unknown [37, 38]. An MRI of chronic osteitis pubis can show less edema but more osseous productive changes with osteophytes, sclerosis, and subchondral cysts secondary to chronic instability at the symphysis (Fig. 5b) [37].

In some cases, on the axial sequences, an abnormal inferior extension of the cleft in the symphyseal fibrocartilage can be seen and has been called a secondary cleft sign (Fig. 5) [20, 39]. This likely represents a microtear of the adductor enthesis. This is important because adductor dysfunction and osteitis pubis frequently coexist, and it has been speculated that adductor dysfunction may precede the development of osteitis pubis [39, 40]. If both pathologies are present, treatment options may need to expand to focus on both pain generators (Fig. 6).

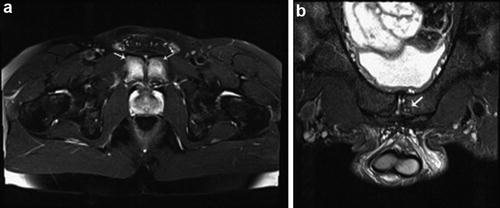

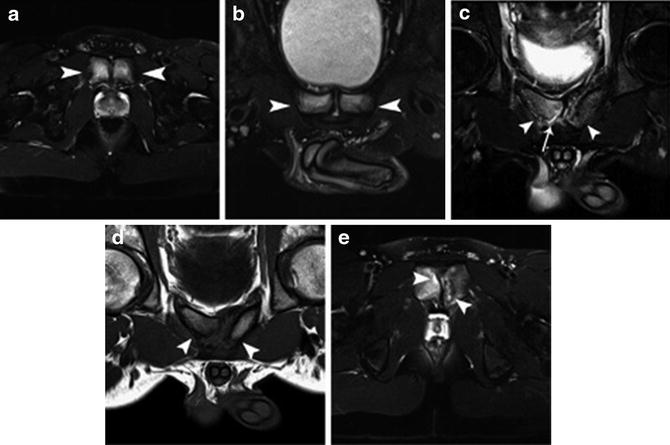

Fig. 6

Osteitis pubis. (a, b) College football player with typical appearance of severe acute osteitis pubis. (a) Large field-of-view axial T2 fat-saturated FSE image of the bony pelvis shows severe acute osteitis pubis (arrowheads). Osteitis pubis extends in the anteroposterior direction involving the pubic body rather than the focal edema localized to the pubic tubercle, which is often seen in unilateral caudal rectus abdominis detachments. (b) Small field-of-view coronal oblique T2 fat-saturated FSE image using a pubalgia protocol demonstrates the severe acute osteitis pubis (arrowheads). No chronic changes are seen, such as degenerative cysts, sclerosis, or osteophytes in this case. (c–e) College soccer player with severe acute or chronic osteitis pubis. (c) Small field-of-view coronal oblique T2 fat-saturated FSE image using a pubalgia protocol demonstrates severe acute or chronic osteitis pubis (arrowheads) with disorganization and resorption predominantly affecting the left pubis. A right secondary cleft is present (arrow). (d) Small field-of-view coronal oblique proton density image using a pubalgia protocol demonstrates severe acute or chronic osteitis pubis (arrowheads) with disorganization and resorption predominantly affecting the left pubis. (e) Large field-of-view axial T2 fat-saturated FSE image of the bony pelvis demonstrates severe acute or chronic osteitis pubis (arrowheads) with disorganization and resorption predominantly affecting the left pubis. Reprinted from [17] with permission from Elsevier

Intra-articular hip pathology such as acetabular labral tears are very common in athletes and are a common differential diagnostic consideration that should be ruled out in patients with groin pain. MRI arthrography has been used for the assessment of intra-articular hip pathology as it has been shown to be superior to conventional MRI in detecting labral tears (87 % vs. 66 % sensitivity and 64 % vs. 79 % specificity, respectively) [41]. The addition of a local anesthetic to the directly injected contrast can also help distinguish intra-articular from extra-articular causes of pain [42].

CT

Computed tomography can be used to more accurately evaluate the bony morphology of the hip joint in the setting of femoroacetabular impingement or osteitis pubis. Measurements of acetabular and femoral neck version and the alpha angle are taken in addition to three-dimensional reconstructions to better characterize pincer and cam morphology. In osteitis pubis, the CT scan may also show marginal “stamp erosions” of the parasymphyseal pubis better than plain X-rays and MRI (Fig. 7) [43].

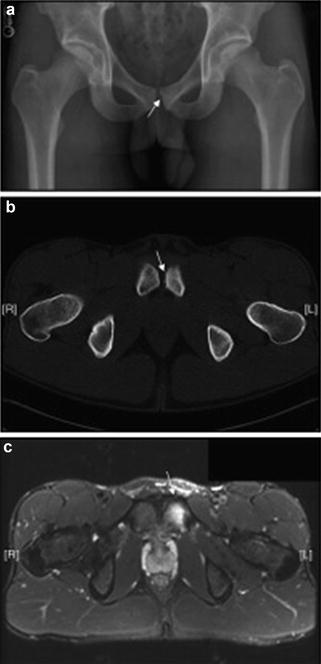

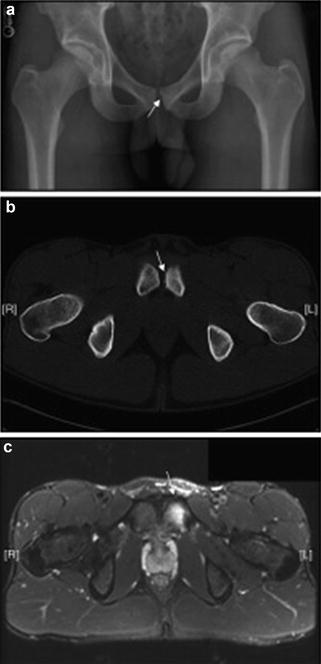

Fig. 7

(a) Anteroposterior radiograph and (b) axial CT of the pelvis demonstrate stamp erosions of the pubic symphysis on the left (arrow). (c) Axial T2-weighted image with fat saturation demonstrates prominent bone marrow edema within the left pubis (arrow). Reprinted from [23] with permission from Elsevier

Bone Scan

Historically the 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate triple-phase bone scan has been used with standard radiographs to evaluate osteitis pubis. The bone scan can also be a helpful screening tool for acute bony pathology including stress fracture or osteomyelitis. Positive bone scans show increased tracer uptake in the region of the pubic symphysis and the parasymphyseal bone, especially on delayed images, but the degree of uptake is poorly correlated with the duration and severity of symptoms [4, 23, 38].

Treatment

Nonoperative

Initial treatment of osteitis pubis should begin with conservative measures typically including rest or activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and physical therapy [26]. As mentioned previously, one theory is that osteitis pubis is caused by increased stress at the pubic symphysis due to imbalance between hip adductors and abdominal muscles. It has been shown that active rehabilitation programs that improve coordination and strength of the counterbalancing muscles that attach to the pelvis can help decrease pain in patients with chronic groin pain [44]. Physical therapy should progress from trunk, pelvic, and hip range of motion to stability exercises and to a more complex strength program. Sport-specific exercises are then introduced. Return to activity is usually based on incremental improvement in pain and the athletes’ willingness to continue with nonsurgical treatment [44]. One case series demonstrated that earlier diagnosis and initiation of treatment led to fewer symptoms and quicker return to play in athletes [44]. Another small case series demonstrated that use of compression shorts reduced groin pain during exercise in 11 patients with osteitis pubis [45].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree