35 Occupational and Recreational Musculoskeletal Disorders

“When job demands … repeatedly exceed the biomechanical capacity of the worker, the activities become trauma-inducing. Hence, traumatogens are workplace sources of biomechanical strain that contribute to the onset of injuries affecting the musculoskeletal system.”2

This chapter discusses the possible association of certain occupational and recreational activities with musculoskeletal disorders. It has been conventional wisdom that “wear and tear” from at least some activities leads to reversible or irreversible damage to the musculoskeletal system.2–5 Despite the apparent logic that work or recreational activities might cause rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders or soft tissue syndromes, this putative association is controversial and perhaps seriously flawed. There are confounding aspects to many of the available data including imprecise diagnostic labels, subjectivity of complaints, anecdotal and survey data, inadequate controls, differing definitions of disease and disability, limited duration of follow-up observations, inadequate epidemiology, inferential observations, difficulty quantifying activities and defining health effects, assumptions of the validity of claims data, variable quality of reported observations, psychologic factors influencing symptoms, and conflicting data.

Occupation-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

Many presumptive work-related musculoskeletal disorders have been described and are summarized in Table 35-1.1–11 These have been reported as sprains, strains, inflammations, dislocations, and irritations. Work-related musculoskeletal injuries comprise at least 50% of nonfatal injury cases resulting in days away from work.12 The cost of work-related disability from musculoskeletal disorders has been equivalent to approximately 1% of the United States’ gross national product, making these entities of considerable societal interest.13 Industries with the highest rates of musculoskeletal disorders include meatpacking, knit-underwear manufacture, motor vehicle manufacture, poultry processing, mail and message distribution, health assessment and treatment, construction, butchery, food processing, machine operation, dental hygiene, data entry, hand grinding and polishing, carpentry, industrial truck and tractor operation, nursing assistance, and housecleaning. There have been imprecise associations between work-related musculoskeletal syndromes and age, gender, fitness, and weight.6,10,11

Table 35-1 Occupation-Related Musculoskeletal Syndromes

| Cherry pitter’s thumb | Gamekeeper’s thumb |

| Staple gun carpal tunnel syndrome | Espresso maker’s wrist |

| Bricklayer’s shoulder | Espresso elbow |

| Carpenter’s elbow | Pizza maker’s palsy |

| Janitor’s elbow | Poster presenter’s thumb |

| Stitcher’s wrist | Rope maker’s claw hand |

| Cotton twister’s hand | Telegraphist’s cramp |

| Writer’s cramp | Waiter’s shoulder |

| Bowler’s thumb | Ladder shins |

| Jeweler’s thumb | Tobacco primer’s wrist |

| Carpet layer’s knee |

From Mani L, Gerr F: Work-related upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders, Primary Care 27:845–864, 2000; and Colombini D, Occhipinti E, Delleman N, et al: Exposure assessment of upper limb repetitive movements: a consensus document developed by the technical committee on musculoskeletal disorders of International Ergonomics Association endorsed by International Commission on Occupation Health, G Ital Med Lav Ergon 23:129–142, 2000.

A number of work-related regional musculoskeletal syndromes have been described. These include disorders of the neck, shoulder, elbow, hand and wrist, lower back, and lower extremities10 (Table 35-2); some of these are discussed in greater detail in other chapters. Neck musculoskeletal disorders were associated with repetition, forceful exertion, and constrained or static postures. Shoulder musculoskeletal disorders occur with work at or above shoulder height, lifting of heavy loads, static postures, hand-arm vibration, and repetitive motion. For elbow epicondylitis, risk factors were overexertion of finger and wrist extensors with the elbow in extension, as well as posture. Hand-wrist tendinitis and work-related carpal tunnel syndrome were noted with repetitive work, forceful activities, flexed wrists, and duration of continual effort.1,10 Hand-arm vibration syndrome (Raynaud-like phenomenon)14 has been linked to the intensity and duration of vibrating exposure. Work-related lower back disorders are associated with repetition, the weight of objects lifted, twisting, and poor biomechanics of lifting.14,15 Other risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders involving the back included awkward posture, high static muscle load, high-force exertion at the hands and wrists, sudden applications of force, work with short cycle times, little task variety, frequent tight deadlines, inadequate rest or recovery periods, high cognitive demands, little control over work, cold work environment, localized mechanical stresses to tissues, and poor spinal support.1

Table 35-2 Selected Literature Describing Regional Occupation-Related Musculoskeletal Syndromes

| Syndrome | No. of Epidemiologic Studies | Odds Ratio/Relative Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Neck pain | 26 | 0.7-6.9 |

| Shoulder tendinitis | 22 | 0.9-13 |

| Elbow tendinitis | 14 | 0.7-5.5 |

| Hand-wrist tendinitis | 16 | 0.6-31.7 |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 22 | 1-34 |

| Hand-arm vibration syndrome | 8 | 0.5-41 |

The development of recommended treatment methods (rehabilitation) for these so-called occupational musculoskeletal disorders has included collaboration by workers, employers, insurers, and health professionals. The process has been divided into three phases: protection from and resolution of symptoms, restoration of strength and dynamic stability, and return to work. This process included symptomatic therapies, physical therapy, and ergonomic evaluation.7 Prognosis for these maladies has not been well studied or defined.8

Until recently, the prevailing view was that many musculoskeletal disorders were consistently and predictably work related. That understanding has now come under considerable scrutiny and criticism.2,16–25 Despite the quantity of published information (see Table 35-2), the previously cited literature about occupational musculoskeletal disorders is now considered flawed; its quality was uneven and perhaps poor in some instances. Definitions of musculoskeletal disorders were imprecise; diagnoses, by rheumatologic standards, were infrequent; studies were usually not prospective, and there were selection biases; psychologic influences and secondary gain were often ignored; questionnaires were often used without validation of subjective complaints; and quantification of putative causative factors was difficult. Indeed, a review of this literature concluded that none of the published studies satisfactorily established a causal relationship between work and distinct medical entities.21 In fact, certain experiences argued powerfully against the notion of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. In Lithuania, for example, where insurance was limited and disability was not a societal expectation or entitlement, “whiplash” from auto accidents did not exist.20 In Australia, when legislation for compensability was made more stringent, an epidemic of whiplash and repetitive-strain injuries abated.22,24 In the United States, too, expressed symptoms correlated closely with the likelihood of obtaining compensation.26 In other cases, ergonomic interventions had no effect on alleged work-related symptoms and close analysis of epidemics of work-related musculoskeletal disorders revealed serious inconsistencies.18 These concerns led the American Society for Surgery of the Hand to editorialize that “the current medical literature does not provide the information necessary to establish a causal relationship between specific work activities and the development of well-recognized disease entities. Until scientifically valid studies are conducted, the society urges the government to exercise restraint in considering regulations designed to reduce the incidence of these conditions because premature regulations could have far-reaching legal and economic effects, as well as an adverse impact on the care of workers.”19

One review summarized that “most believe scientific data are insufficient to establish a definite causal relationship of these so-called cumulative trauma disorders to the worker’s occupation, and many believe the issue has become a sociopolitical problem.”9 Hadler2,16–18 has written particularly forcefully that popular notions about work-related musculoskeletal disorders have been based on inadequate science. Others, too, have expressed serious reservations about the cumulative trauma disorder hypothesis including the Industrial Injuries Committee of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, the Working Group of the British Orthopaedic Association, and the World Health Organization.2,16–18,21,23

An appreciation of the importance of psychosocial factors influencing work disability has emerged. These factors included lack of job control, fear of layoff, monotony, job dissatisfaction, unsatisfactory performance appraisals, distress and unhappiness with co-workers or supervisors, repetitive tasks, duration of work day, poor quality of sleep, perceptions of air quality and ergonomics, poor coping abilities, divorce, low income, less education, poor social support, presence of chronic disease, poor sleep quality, self-rated perception of poor air quality, and poor office ergonomics.2,16–30 This is reminiscent of the story of silicone breast implants and their presumed association with rheumatic disease. In this instance—as seems to be the case with work-related musculoskeletal disorders—there was a coalescence of naïvely simplistic assumptions, untested hypotheses, confusion between the repetition of hypotheses and their scientific validation, media exaggeration, and public advocacy intertwined with politics and governmental regulatory agencies, dollar jackpots, litigation, and inadequate science. All these elements confounded and perverted the silicone breast implant story31,32 and may have confused the interpretation of evidence-based work-related musculoskeletal disorders as well. More good-quality, standardized investigation is necessary to learn about work-related musculoskeletal disorders and to clearly identify the circumstances in which they occur. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders probably exist, but they are likely to be less pervasive and less noxious than originally thought.

Occupation-Related Rheumatic Diseases

Osteoarthritis

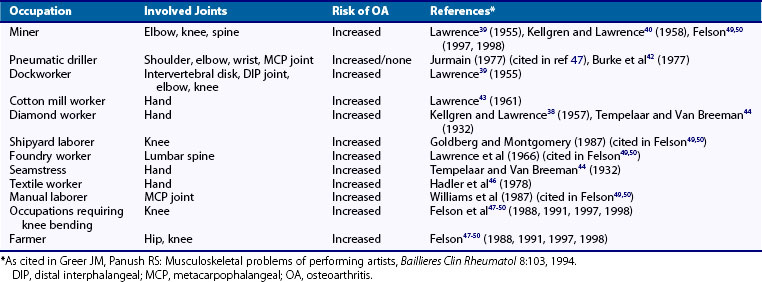

Is osteoarthritis (OA) caused, at least in part, by mechanical stress? One analytic approach to determining a possible relationship between activity and joint disease is to consider the epidemiologic evidence that degenerative arthritis may follow repetitive trauma. Most discussions of the pathogenesis of OA include a role for “stress.”33–50 Several studies have suggested an increased prevalence of OA of the elbows, knees, and spine in miners38–40; of the knees in floor layers and in other occupations requiring kneeling; of the knees in shipyard workers and a variety of occupations involving knee bending; of the shoulders, elbows, wrists, and metacarpophalangeal joints in pneumatic drill operators42; of the intervertebral disks, distal interphalangeal joints, elbows, and knees in dockworkers39; of the hands in cotton workers,43 diamond cutters,38,44 seamstresses,44 and textile workers45,46; of the knees and hips in farmers; and of the spine in foundry workers47 (Table 35-3). Population studies have noted increased hip OA in farmers, firefighters, mill workers, dockworkers, female mail carriers, unskilled manual laborers, fishermen, and miners and have reported increased knee OA in farmers, firefighters, construction workers, house and hotel cleaners, craftspeople, laborers, and service workers.47–50 Activities leading to an increased risk for premature OA involve power gripping, carrying, lifting, increased physical loading, increased static loading, kneeling, walking, squatting, and bending.47–50 Recent studies and systematic reviews have confirmed/adduced that heavy lifting and crawling but not climbing were associated with knee and hip OA; individual studies were variable, often small, and with interpretive limitations.51–54 The effect of body mass index in work-related osteoarthritis appeared to predispose toward the development of knee osteoarthritis, with primarily valgus malalignment.55–57

Studies of skeletons of several populations have suggested that age at onset, frequency, and location of osteoarthritic changes were directly related to the nature and degree of physical activities.58 However, not all these studies adhered to contemporary standards, nor have they been confirmed. One report, for example, failed to find an increased incidence of OA in pneumatic drill users and criticized inadequate sample sizes, lack of statistical analyses, and omission of appropriate control populations in previous reports.40 The investigators further commented that earlier work was “frequently misinterpreted” and that their studies suggested that “impact, without injury or preceding abnormality of either joint contour or ligaments, is unlikely to produce osteoarthritis.”42

Do epidemiologic studies of OA implicate physical or mechanical factors related to disease predisposition or development? The first national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1971 to 1975 (HANES I) and the Framingham studies explored cross-sectional associations between radiographic OA of the knee and possible risk factors.47–65 Strong associations were noted between knee OA and obesity and those occupations involving the stress of knee bending, but not all habitual physical activities and leisure-time physical activities (running, walking, team sports, racquet sports, and others) were linked with knee OA.33–35,66–68 (See Chapter 98 for more information concerning the pathogenesis of OA.)

Other Occupational Rheumatologic Disorders

Certain rheumatic diseases other than repetitive strain or cumulative trauma disorders have been associated with occupational risks. These included reports of reflex sympathetic dystrophy after trauma; Raynaud’s phenomenon with vibration or exposure to chemicals (polyvinyl chloride); autoimmune disease from teaching school, farming and occupations with exposure to animals and pesticides, mining, textile machine and decorating operations50,69; scleroderma from chemicals, silica, solvents, and use of vibrating tools70–74; scleroderma-like syndromes from rapeseed oil and l-tryptophan73; systemic lupus erythematosus from sun, silica, mercury, pesticides, nail polish, paints, dye, canavanine, hydrazine, solvents75,76; lupus, scleroderma, and Paget’s disease from pets77; granulomatous vasculitis from mercury and lead78; primary systemic vasculitis from farming, silica, solvents, and allergy70,79; gout (saturnine) and hyperuricemia with lead intoxication80; and rheumatoid arthritis (Caplan’s syndrome) with silica, farming, mining, quarrying, electrical work, construction and engine operation, nursing, religious, juridical, and other social science–related work81,82(Table 35-4).

Table 35-4 Other Occupation-Related Rheumatic Diseases

| Disease or Syndrome | Occupation or Risk Factor |

|---|---|

| Reflex sympathetic dystrophy | Trauma |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Vibration |

| Chemicals (polyvinyl chloride) | |

| Autoimmune disease | Teaching school |

| Scleroderma | Chlorinated hydrocarbons |

| Organic solvents | |

| Silica | |

| Scleroderma-like syndromes | Rapeseed oil |

| l-Tryptophan | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Canavanine, hydrazine, mercury, pesticides, solvents |

| Lupus, scleroderma, and Paget’s disease | Pet ownership |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (Caplan’s syndrome) | Silica |

| Gout (saturnine) | Lead |

Recreation- And Sports-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

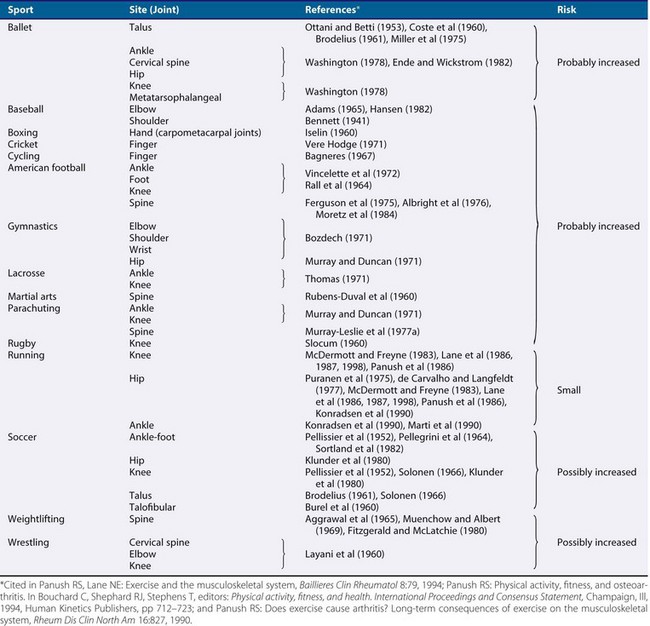

Do recreational or sports-related activities lead to musculoskeletal disorders? It has been suggested that the risk of joint degeneration is increased by participation in sports that have high impact levels with torsional loading.83 The presence of prior joint injury, surgery, arthritis, joint instability and/or malalignment, neuromuscular disturbances, and muscle weakness also predisposed to higher risks of joint damage during sports participation.83 Patients with sports injuries (such as from downhill skiing and football) to the anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligaments frequently developed the chondromalacia patellae and radiographic abnormalities of OA (20% to 52%).33–35 Retrospective studies suggest that the development of OA may be associated with varus deformity, previous meniscectomy, and relative body weight.84,85 Both partial and total meniscectomies have been associated with degenerative changes. Early joint stabilization and direct meniscus repair surgery may decrease the incidence of premature OA. These observations supported the concept that abnormal biomechanical forces, either congenital or secondary to joint injury, are important factors in the development of exercise-related OA.33–35 Other factors considered important in the development of sports-related OA included certain physical characteristics of the participant, biomechanical and biochemical factors, age, gender, hormonal influences, nutrition, characteristics of the playing surface, unique features of particular sports, and duration and intensity of exercise participation, as has been reviewed extensively elsewhere.33–35 It is increasingly recognized that biomechanical factors have an important role in the pathogenesis of OA.

Is regular participation in physical activity associated with degenerative arthritis? Several animal studies (of tentative scientific relevance, but interesting) have suggested a possible relationship between exercise and OA. For example, it has been stated that the husky breed of dog has increased hip and shoulder arthritis associated with pulling sleds, that tigers and lions develop foreleg OA related to sprinting and running, and that racehorses and workhorses develop OA in the forelegs and hind legs, respectively,86 consistent with their physical stress patterns.33,35 Rabbits with experimentally induced arthritis in one hind limb did not develop progressive OA when exercised on treadmills,87–92 but sheep in normal health walking on concrete did develop OA.93 Other studies found that beagle dogs running 4 to 20 km a day did not develop OA.94 Although these observations were not entirely consistent, they suggested that physical activities in some circumstances might predispose to degenerative joint disease.

There have been some pertinent observations in human studies33–35 (Table 35-5). Wrestlers were reported to have an increased incidence of OA of the lumbar spine, cervical spine, and knees; boxers, of the carpometacarpal joints; parachutists, of knees, ankles, and spine, which was not confirmed36; cyclists, of the patella; cricketers, of the fingers; basketball and volleyball, of the knees55; athletes involved in sports requiring repetitive overhead throwing such as baseball, tennis, volleyball players, and swimmers, of early glenohumeral arthritis95; meniscal and anterior cruciate ligament injuries incurred in youth-related sports, of knee osteoarthritis96; soccer players of talar joint, ankle, cervical spine, knee, and hip OA.33–35,97–99 Studies of American football players have suggested that they are susceptible to OA of the knees, particularly those who sustained knee injuries while playing football.37 Among football players (average age, 23 years) competing for a place on a professional team, 90% had radiographic abnormalities of the foot or ankle, compared with 4% of an age-matched control population; linemen had more changes than did ball carriers or linebackers, who in turn had more changes than did flankers or defensive backs. All those who had played football for 9 years or longer had abnormal findings on radiography.33–37 Most of these studies suffered in several respects: criteria for OA (or “osteoarthrosis,” “degenerative joint disease,” or “abnormality”) were not always clear, specified, or consistent; duration of follow-up was often not indicated or was inadequate to determine the risk of musculoskeletal problems at a later age; intensity and duration of physical activity were variable and difficult to quantify; selection bias toward individuals exercising or participating versus those not exercising or participating was not weighted; other possible risk factors and predispositions to musculoskeletal disorders were rarely considered; studies were not always properly controlled, and examinations were not always “blind”; little information regarding nonprofessional, recreational athletes was available; and little clinical information about functional status was provided.

Table 35-5 Sports Participation and Alleged Associations with Osteoarthritis

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|