Nerve Entrapment Syndromes

Anish R. Kadakia

Aaron A. Bare

Steven L. Haddad

Pain from nerve entrapment is often misdiagnosed and incorrectly understood. Nerve entrapment disorders of the foot and ankle require an understanding of both anatomy and clinical symptoms to lead the clinician to a correct diagnosis. The differential diagnosis should always include proximal neural lesions from the spine or conditions such as systemic disease. Isolated nerve problems may be static or functional. Functional symptoms are often seen during athletics, when increased activity causes temporary impingement. In this situation, the common workup of radiographs or other imaging studies usually does not assist in making a diagnosis. These diagnoses require dynamic activity with testing. An appreciation of nerve conduction tests as well as their applications often helps to confirm the diagnosis. For entrapment syndromes, the physical examination generally provides sufficient information to institute treatment. Treatment for these disorders is often conservative and entails relieving pressure in the affected region. Surgical management is reserved for refractory cases and requires careful preoperative planning and intraoperative execution to avoid postoperative scarring and complications. Such complications may lead to increased pain and significant patient dissatisfaction.

INTERDIGITAL NEUROMA (MORTON NEUROMA)

The interdigital neuroma was first described in 1845 as a condition involving “the plantar nerve between the third and fourth metatarsal bones.” In 1876, Morton related it to the fourth metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint and hypothesized that this represented a neuroma or possibly hypertrophy of the lateral plantar nerve. The term Morton neuroma is used now commonly to describe an interdigital neuralgia of the forefoot.

PATHOGENESIS

Etiology

An interdigital neuroma is thought to evolve as an entrapment neuropathy of the common digital nerve. Chronic pressure on the digital nerve as it courses beneath the transverse intermetatarsal ligament results in perineural and endoneural fibrosis with frequent degeneration of the myelinated fibers as verified histologically. Seldom are the histologic changes seen proximal to the intermetatarsal ligament, which lends further support to a compressive etiology.

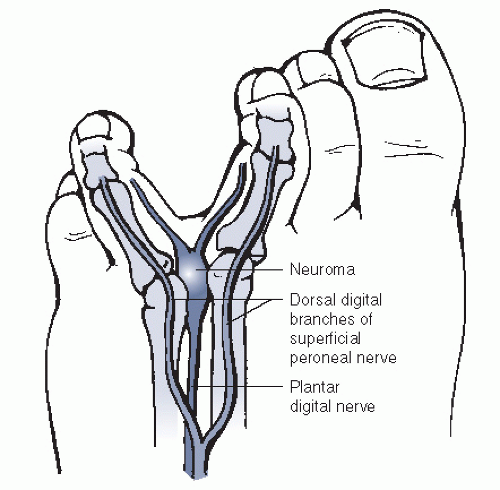

The anatomy of the digital nerves was previously considered to predispose a patient to a Morton neuroma in the third web space. Branches from the lateral and medial plantar nerves enter the web spaces as common digital nerves. Traditionally, it was thought that both the medial and the lateral plantar nerves send branches to the third web space creating a nerve tethered over the flexor digitorum brevis that predisposed it to increased microtrauma (Fig. 4.1). However, it has been shown that a medial communicating branch to the third web space is present in only 27% of the population. This study proposed that the middle web space etiology of interdigital neuroma may instead be related to the anatomic finding of increased narrowness of the second and third interspaces.

Metatarsal mobility may also contribute to the pathology. The medial three rays are firmly attached to the cuneiform bones and are more rigidly fixed than the lateral two metatarsal attachments to the cuboid. The third web space is imbalanced by an immobile third ray and a mobile fourth ray, which may lead to abnormal motion within the web space. However, this theory does not explain the prevalence of interdigital neuromata in the second web space.

Narrowed toe box shoes and high heels may also contribute to neuroma formation. Dorsiflexion of the MTP joints causes plantarflexion of the metatarsal heads. Theoretically, as the metatarsal heads translate plantarward, the digital nerve may become tethered beneath the transverse intermetatarsal ligament, resulting in entrapment. High-fashion shoes cause this deformity—making the tethered nerve subject to repetitive trauma through increased compression

by the metatarsal heads and stretching over the intermetatarsal ligament. Occasionally, traumatic mechanisms such as falls, penetrating injuries, or crush injuries may lead to neuroma development. Extrinsic factors may also influence neuroma formation. Ganglions or synovial cysts arising from the MTP joint may cause direct pressure on the digital nerve. Degeneration of the MTP joint capsule from inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis often causes subluxation of the MTP joint and stretches the nerve. Such distortion of the MTP joint may also compress the bursae surrounding the ligament, resulting in increased pressure on the surrounding tissues, which may cause symptoms in approximately 10% to 15% of patients with interdigital neuromata.

by the metatarsal heads and stretching over the intermetatarsal ligament. Occasionally, traumatic mechanisms such as falls, penetrating injuries, or crush injuries may lead to neuroma development. Extrinsic factors may also influence neuroma formation. Ganglions or synovial cysts arising from the MTP joint may cause direct pressure on the digital nerve. Degeneration of the MTP joint capsule from inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis often causes subluxation of the MTP joint and stretches the nerve. Such distortion of the MTP joint may also compress the bursae surrounding the ligament, resulting in increased pressure on the surrounding tissues, which may cause symptoms in approximately 10% to 15% of patients with interdigital neuromata.

Epidemiology

Women have an 8 to 10 times increased prevalence of interdigital neuromas, which is believed to be secondary to constrictive, high-heeled footwear.

Pathophysiology

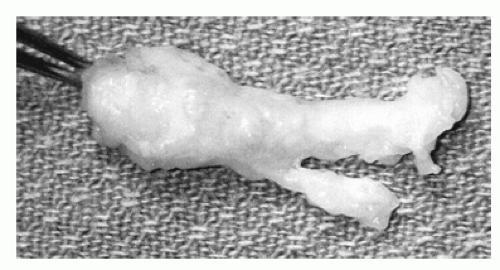

Histologic analysis has revealed that the nerve is affected distal to the intermetatarsal ligament. Fusiform swelling of the nerve has generated the term neuroma. Chronic entrapment leads to sclerosis and edema of the endoneurium, thickening of the perineurium, deposition of eosinophilic material, and demyelination of nerve fibers distal to the ligament. The culmination of this pathologic process is an increased diameter of the affected nerve through intrasubstance hypertrophy and swelling (Fig. 4.2).

DIAGNOSIS

History and Physical Examination

Classically, a patient with a symptomatic interdigital neuroma complains of pain located on the plantar aspect of the foot at or distal to the metatarsal heads. The pain is described as burning, often with radiation to the toes. Seldom do the symptoms radiate proximally. More than 50% of patients with a documented Morton neuroma report at least one of the following symptoms: plantar pain that increases by walking (91%), relief of pain by rest of the involved foot (89%), relief of pain by removing the shoe (70%), pain radiating into the toes (62%), and burning pain (54%). Occasionally, a patient may report a feeling of an object “moving around” in the offending area or the feeling of walking on a marble that is thought to be a result of the nerve becoming temporarily entrapped beneath the metatarsal head and then released. The symptoms are generally aggravated by activity or footwear that compresses the forefoot or elevates the heel. Patients often report improvement with wearing of athletic shoes.

Figure 4.2 A specimen of an interdigital neuroma illustrates its bulbous shape and size, located at the digital nerve branch point. |

The historically reported rate of double neuromas has been 1.5% to 3.0%. This has been recently disputed with a more contemporary reported rate of 8.9%. Although the rate of concurrent neuromas may be higher than previously reported, it is imperative that alternate causes for the forefoot pain be excluded before making this diagnosis.

Physical examination elicits tenderness in the plantar web space, with radiation to the toe.

The patient should be examined standing for a hammer toe, claw toe, or crossover toe.

The presence of an equinus deformity should be determined.

The web space should be examined for fullness.

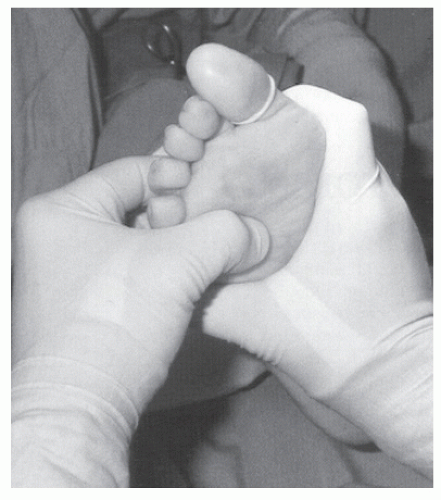

The examiner can grasp both metatarsal heads adjacent to the suspected neuroma and, with one thumb, apply dorsal pressure to the plantar web space, which displaces the nerve between the metatarsal heads.

Increasing pressure is applied on both metatarsal heads in a mediolateral direction, forcing each metatarsal head toward the nerve.

With this increased pressure on the nerve, the nerve is forced plantarward, creating a clicking sound as it leaves the interspace.

This maneuver, called Mulder sign (Fig. 4.3), causes a crunching or clicking perception in the second or third web interspace.

If this sensation also creates pain or reproduction of the patient’s symptoms, it is diagnostic of an interdigital neuroma.

Palpation of the plantar aspect of the foot may reveal a ganglion or synovial cyst.

The overall sensory and vascular examination is typically normal. However, any signs of dysvascularity, including lack of palpable pulses or hair loss should be further evaluated before surgical intervention.

Figure 4.3 Mulder sign can be elicited by palpating the space between the metatarsal head with pressure applied both dorsally and plantar.

The metatarsal heads should be palpated and checked for fat pad atrophy.

Differentiating between metatarsalgia and interdigital neuromata is critical, and the location of pathology is merely a few millimeters apart.

If pain exists in the web space as well as over the metatarsal heads, care should be taken in diagnosing a Morton neuroma (Box 4.1).

Repeat evaluation or further imaging is warranted.

BOX 4.1 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF AN INTERDIGITAL NEUROMA

MTP Joint Disorders

Degeneration of plantar pad or capsule

Synovitis of MTP joint caused by nonspecific synovitis or rheumatoid arthritis

Subluxation or dislocation of MTP joint

Freiberg infraction

Arthrosis of MTP joint

Pain of Neurogenic Origin Unrelated to Interdigital Neuroma

Degenerative disk disease

Tarsal tunnel syndrome

Lesion of medial or lateral plantar nerve

Peripheral neuropathy

Lesions of Plantar Aspect of the Foot

Synovial cysts

Soft tissue not involving MTP joint (e.g., ganglion, lipoma, synovial cyst)

Soft tissue tumor (e.g., lipoma)

Tumor of metatarsal bone

From Mann RA. Disease of the nerves. In: Coughlin MJ, ed. Surgery of the adult foot and ankle. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1993:507.

Radiologic Features

Most patients with a symptomatic interdigital neuroma can be diagnosed with physical examination and history, without the need for additional studies.

Three weight-bearing views of the foot can be performed to help rule out any pathologic process of the MTP joint.

Soft-tissue imaging is not routinely required to obtain the diagnosis of a neuroma. For clinical cases with a questionable diagnosis, some experts have advocated the use of ultrasonography or high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Ultrasonography has demonstrated a high sensitivity with a variable specificity in the diagnosis of a neuroma. One study noted that ultrasound accurately predicted the size and location of the neuroma in 98% of 55 neuromas without a false-positive reading. However, other studies have demonstrated a 95% sensitivity, with only a 65% specificity rate.

The use of MRI remains controversial. Before the development of high-resolution scanners, the predictive value of MRI was low. Currently, an MRI scan may detect aberrant pathology such as a cyst or ganglion. However, its use for detection and diagnosis of an interdigital neuroma remains open to debate.

In general, the diagnosis is usually made without the use of ultrasound or MRI and should be considered with rare clinical presentations.

Diagnostic Workup

For a patient with a classic presentation, diagnosis of an interdigital neuroma can be made based solely on the history and physical examination. For patients with an inconclusive physical examination, further evaluation is warranted.

Ultrasonography can be considered.

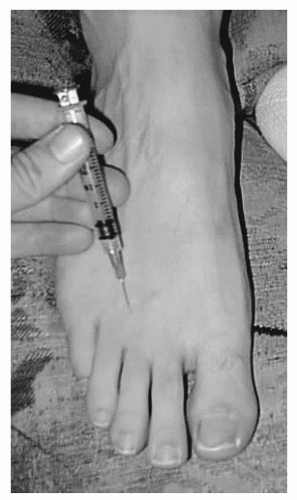

Alternatively, a diagnostic injection can be performed.

With the needle penetrating the transverse intermetatarsal ligament, 2 mL of lidocaine is injected into the web space through a dorsal approach. The tip of the needle should abut on the plantar skin and backed off 1 to 2 mm to reliably place the medication adjacent to the nerve, and not through the nerve. The physician should not place his or her opposite hand on the plantar surface of the foot, as the patient may produce a sudden dorsiflexion movement of the ankle during injection, injuring the physician’s hand through direct penetration of the injection needle.

A successful injection should result in numbness in the appropriate web space and cessation of pain temporarily. This result, however, should be interpreted with caution because other pathologic processes in the region, such as MTP arthritis or bursal inflammation, can also be partially relieved with local injection owing to spillover of the medication. Injections that result in numbness without relief of pain are not consistent with a neuroma.

Some clinicians advocate the addition of cortisone to the injection; others avoid cortisone in younger patients with a suspected neuroma. The hypothesized effect of cortisone is reduction in the inflammation of the neuroma along with atrophy of the web space tissue to decrease compression. Detractors of cortisone injections believe that the potential for fat pad atrophy,

degeneration or rupture of the plantar plate or collateral ligaments, outweighs the potential benefits of the injection. Such injections can lead to a claw toe or crossover toe deformity developing as a result of weakened tissues. These complications are more closely associated with repeated cortisone injections into the web space.

The success rates with cortisone injections have varied. Retrospective reviews have reported results that range from transient pain relief to 80% resolution of pain at 2 years of follow-up. A recent prospective study utilizing ultrasound guided injections demonstrated complete relief in 28% of patients and significant relief with minor residual pain in 44% of patients at 9 months of follow-up. The authors reported no complications with this injection technique. The use of a single cortisone injection is appropriate in the workup and management of a neuroma and has the potential to provide long-term pain relief with a low reported rate of complications. However, multiple injections can lead to fat pad atrophy and potential soft-tissue disruption and should only be used with caution.

TREATMENT

Nonsurgical Treatment

Footwear modification is the hallmark of treatment of an interdigital neuroma.

Recommending wider toe box shoes, metatarsal pads to alter the position of the metatarsal heads, and an arch support may help the patient.

Patients should avoid shoes that constrict the forefoot or have elevated heels.

If a metatarsal pad is used, it is placed proximal to the involved interspace. This device helps to splay the metatarsal heads and decompress the thickened nerve.

Cortisone injection is an option for patient’s refractory to footwear adjustments (Fig. 4.4).

The success of multiple injections has not been clearly elucidated and should be considered with caution because of the potential complications.

The use of multiple ethanol injections has also been advocated as a surgical alternative. The basic science behind intralesional alcohol injection is the ability of 20% dehydrated alcohol to inhibit neuron cell function in vitro. Espinosa et al. have recently demonstrated a 22% success rate with an average of 4.1 injections required. This is in contrast to previously reported results that have suggested a 71% to 82% rate of complete pain relief after 1 year of follow-up. No major complications have been reported; however, the injection can result in extreme pain leading to cessation of the injection before completion. Given the variable reported relief and the discomfort associated with multiple injections, this technique is not currently performed by the authors.

Surgical Treatment

When conservative management fails, surgical excision of the neuroma should be considered. The authors do not advocate isolated release of the intermetatarsal ligament secondary to the known histopathologic changes that occur with a Morton neuroma. Release of the ligament does not correct the pathologic process and thus may not result in cessation of pain. In the setting of adjacent neuromas, the excision of one neuroma and transection of the intermetatarsal ligament of the web space that has a macroscopically normal appearing nerve can be performed to prevent anesthesia of the middle digit. However, if both nerves appear thickened and abnormal, resection should be performed.

Figure 4.4 Local injection of an interdigital neuroma is performed from the dorsum of the foot, directly over the neuroma, directing the needle between the metatarsal heads. |

Successful results of both the dorsal and the plantar approaches have been reported. A retrospective review performed by Akermark et al. reviewed the results at 2 years from neuroma resection by either a dorsal or a plantar approach in 125 patients. The intermetatarsal ligament was transected with the dorsal approach and left intact with the plantar approach. Confirmation of neuroma resection was performed with histology in all patients. No significant difference with respect to overall satisfaction was identified between the groups. However, the patients who underwent a plantar approach had significantly less complication rates, sensory loss, and sick leave weeks. They did note a 5% missed neuroma resection rate with a dorsal approach and a 5% hypertrophic painful scar formation in the plantar group. The surgeon should utilize the approach that they are most comfortable with, given the similar rates of patient satisfaction for the treatment of a primary neuroma.

A plantar approach is advocated for revision surgery secondary to superior visualization and to allow for more proximal resection. As previously mentioned, advanced imaging studies can be obtained before surgical intervention in patients with failed conservative management and atypical presentation.

Both the dorsal and the plantar approaches allow visualization of the intermetatarsal ligament and the involved nerve (Fig. 4.5).

The nerve should be completely visualized and transected proximal to the metatarsal heads to help prevent the development of a painful residual stump neuroma.

The nerve can be released distally first to prevent retraction before amputation.

Dorsiflexion of the ankle following nerve transection pulls the nerve proximally into the midfoot.

Meticulous hemostasis before closure is critical for two reasons:

It lessens the risk of postoperative scarring, which

may cause entrapment of the nerve.

It lowers the risk of a postoperative hematoma in the “dead space” that may lead to subsequent infection.

Some clinicians advocate sparing the intermetatarsal ligament if possible to preserve continuity of the metatarsals following nerve transection. This modification of the traditional procedure carries with it the risk of inadequate visualization of the nerve and subsequent insufficient resection with a dorsal approach (Fig. 4.6).

Postoperatively, a compression dressing is applied over the forefoot, and the patient is allowed to walk in a postoperative shoe.

Sutures are traditionally removed around 2 weeks following surgery. This, of course, is based on the type of incision closure.

Transition to an athletic shoe is routinely achieved by 2 weeks. The patient is instructed to perform active and

passive ranges of motion exercises of the digits to prevent postoperative contracture.

Occasionally, physical therapy with ultrasound is required to mobilize proliferative scar tissue, which may cause a secondary nerve entrapment.

Results and Outcomes

Surgical excision of the involved nerve has a success rate ranging from 75% to 90%. Mann and Reynolds reported 71% “essentially asymptomatic” patients and a 14% failure rate more than 1 year following the procedure. The results did not vary with nerve removal from either the second or the third web space. Patients can be expected to have numbness in the interspace as well as plantar numbness adjacent to the interspace.

The most frustrating complication of neuroma surgery is a painful stump neuroma. Recurrence of pain can be attributed to two causes:

The nerve was excised as a result of an incorrect diagnosis. Usually, these patients present with recurrent symptoms soon after the surgery was performed.

A stump neuroma may develop, leading to similar symptoms. Up to 12 months is required for the development of a symptomatic, painful stump neuroma after the original surgery. Thus, the recurrence of symptoms after more than a year of relief suggests a recurrent neuroma.

Treatment for a recurrent neuroma is similar to index neuroma surgery, although the plantar approach is preferred because it allows improved visualization proximal to the metatarsal heads. Patients should be informed that a secondary exploration for recurrent neuroma through either approach results in poor outcome of 20% to 40% of the time.

TARSAL TUNNEL SYNDROME

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is caused by entrapment of the tibial nerve or one of its terminal branches (the medial or lateral plantar nerve) in the lower leg or ankle region. The flexor retinaculum lies superficial to the path of the tibial nerve, creating the roof of the tarsal tunnel; this structure originates from the posterior medial malleolus and inserts into the calcaneus. The clinical presentation varies depending on the location of entrapment within the tarsal tunnel. Specific attention to the patient’s complaints and as an understanding of the involved anatomy helps the physician localize the area of impingement.

PATHOGENESIS

Etiology

The different causes for tarsal tunnel syndrome include the following:

Trauma: It is the most common identifiable cause of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Fractures of the hindfoot can reduce the space within the tarsal tunnel. In addition, traumatic synovitis of the flexor tendons decreases the available space within the tarsal tunnel.

Space-occupying lesions: They can create increased pressure within the tarsal tunnel, such as ganglion cysts, lipomas, neurilemomas, varicosities, accessory muscles, and proliferative synovitis.

Bony architecture: A talocalcaneal coalition, an enlarged or displaced os trigonum.

Flexor retinaculum: Covers the tarsal tunnel and may impinge on the tibial nerve.

Hindfoot deformity: Heel valgus with an abducted forefoot has been demonstrated to increase the tension on the tibial nerve. Heel varus with a pronated forefoot results in a shortened abductor hallucis, and this is hypothesized to increase the diameter of the muscle, therefore decreasing the available space of the distal tarsal tunnel.

Pathophysiology

The tarsal tunnel comprises a fibrosseous tunnel beginning in the posteromedial leg and traveling behind the medial malleolus.

The tunnel is bordered by the distal tibia anteriorly and by the posterior border of the talus and calcaneus posteriorly.

Covering the tunnel is the flexor retinaculum, which begins up to 10 cm proximal to the medial malleolus.

The contents of the tunnel include the tibial nerve, the posterior tibial artery and vein, the posterior tibial tendon, the flexor hallucis longus tendon, and the flexor digitorum longus tendon.

Bifurcation of the tibial nerve into the medial and lateral plantar nerves proximal to the tarsal tunnel may predispose patients to tarsal tunnel syndrome. The incidence varies from 4% to 7% of patients and creates a larger cross-sectional area that can lead to compression within the tarsal tunnel.

The tibial nerve has an extensive blood supply through the course of the tarsal tunnel. Thus, nerve ischemia does not appear to contribute to the clinical picture.

Symptoms often arise distal to the site of compression, although this is not mandatory.

Classification

Attempts have been made to categorize tarsal tunnel syndrome by location. Tarsal tunnel syndrome can be separated into proximal and distal subsets based on the location of the pathology.

Proximal compression results from compression proximal to the branching of the tibial nerve into the plantar nerves. Therefore, the entire tibial nerve distribution is affected below the ankle.

The distal syndrome results from impingement distal to a terminal nerve branch, commonly at either the medial or lateral plantar nerves.

Distal or plantar nerve entrapment can be divided into two separate entities—medial and lateral plantar nerve entrapments.

Medial plantar nerve impingement occurs at the fibromuscular tunnel formed by the abductor hallucis

and the navicular tuberosity. Afflicted patients may suffer from pes planovalgus or they may be distance runners, leading to a predisposition for this condition. Often referred to as “jogger’s foot,” this syndrome causes a burning pain along the medial arch that radiates into the first, second, third, and part of the fourth toes.

Lateral plantar nerve entrapment, more common than medial plantar nerve entrapment, occurs as the nerve crosses beneath the foot. One such manifestation is entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve, which can lead to significant heel pain. Distal to this nerve branch, the lateral plantar nerve courses obliquely in a separate tunnel across the plantar surface of the foot. The acute bend in this tunnel, along with its relatively decreased vascular supply compared with that of the medial plantar nerve, is believed to lead to its greater incidence.

DIAGNOSIS

History and Physical Examination

The clinical presentation of this disorder can vary significantly. In general, patients describe a diffuse radiating, burning, tingling sensation, or numbness on the plantar aspect of the foot. Eliminating tendon or joint pathology is important in the differential diagnosis. Proximal radiation of the pain occurs in one-third of patients and is termed the Valleix phenomenon. Usually, tarsal tunnel symptoms are too diffused to originate from a specific tendon around the ankle. Some patients may generalize their symptoms to the posteromedial ankle or describe global paresthesias of the foot. Symptoms are generally exacerbated by activity or exercise and improve with rest. Some patients may complain of sympvtoms at night from their sleeping posture or from direct pressure on the tunnel.

It is important to ascertain from the history the presence of concomitant injuries or illnesses. Rheumatologic diseases can lead to extensive tenosynovitis within the tarsal tunnel. Lumbar spine disorders, such as herniated nucleus pulposus, can cause lower extremity radiculopathy, mimicking symptoms. Systemic diseases causing nerve damage include, but are not limited to, alcoholism, diabetes, and vitamin deficiencies. Furthermore, the “double crush” phenomenon, which includes a proximal lesion or systemic condition in conjunction with the distal lesion, should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Percussion of the tibial nerve or its branches within the tunnel should recreate the paresthesias.

Direct compression of the tibial nerve within the tunnel may recreate plantar symptoms. Often, the compression must be held for 30 seconds or more to duplicate the patient’s symptoms.

The sensory and vascular examinations are usually unremarkable.

Long-standing symptomatic nerve compression may lead to intrinsic muscle weakness and atrophy, most often manifested as a cavus foot and/or as claw toes.

Evaluating the patient’s stance and gait may reveal pes planovalgus or forefoot abduction, either of which may create increased tension on the tibial nerve within the tunnel.

Palpation along the entire tunnel may reveal space-occupying lesions, such as ganglia.

A lumbar spine examination to evaluate for spinal pathology or the double crush phenomenon is mandatory.

Radiologic Features

Radiographs of the ankle and foot can be obtained to identify primary bone pathology such as an exostosis or a tarsal coalition.

Computed tomography is useful to further evaluate suspected primary bone pathology.

MRI may reveal a space-occupying lesion or varicosities creating tunnel impingement. One study found that nearly 90% of patients with clinically diagnosable tarsal tunnel syndrome had identifiable MRI abnormalities.

Electrodiagnostic Studies

Electrodiagnostic studies can have up to 90% accuracy in diagnosing tarsal tunnel syndrome. The complete electro-diagnostic evaluation includes both motor and sensory nerve conduction studies and electromyography. Slowed conduction through and distal to the tunnel as well as fibrillation potentials in the intrinsic musculature are positive findings. Abnormal sensory conduction velocity is a more sensitive (90%) finding compared with abnormal terminal motor latency (54%). Lack of abnormal motor latency therefore is insufficient to rule out tarsal tunnel syndrome. Even though the tests can be accurate, the electrodiagnostic results do not correlate well with the surgical findings or postsurgical clinical results. Therefore, electrodiagnostic testing confirms the suspected clinical diagnosis or rules out a coexisting proximal lesion rather than making the specific diagnosis.

TREATMENT

Nonsurgical Treatment

In general, space-occupying lesions causing tarsal tunnel syndrome respond best to surgical management (Fig. 4.7). For patients without identifiable lesions, conservative management should be attempted before surgical intervention.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications can be used to decrease inflammation and local irritation around the nerve.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree