Physical Examination and Orthotics

Ryan C. Goodwin

James J. Sferra

Eva Asomugha

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A thorough history and physical examination constitute the cornerstone of any medical encounter that ultimately leads to a correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment. This chapter focuses on physical examination elements specific to the foot and ankle and underscores the fact that a systematic approach provides consistent, reproducible information in an effort to minimize missed diagnoses and simultaneously optimize efficiency. General principles of orthotic management and specific examples related to the foot and ankle are discussed.

PATIENT HISTORY

The importance of a carefully obtained history can never be overstated. Even though a comprehensive history is helpful, certain key historical aspects specific to the foot and ankle are essential. Patient age, gender, occupation, and recreational activities provide a foundation for the patient encounter. Occupational requirements and shoe-wear preferences are also helpful.

The patient’s chief complaint should always be elicited. Pain is typically the primary complaint for which people seek care; however, other complaints such as deformity, swelling, instability, and stiffness may be the patient’s main concern. Precipitating and relieving factors that affect the patient’s symptoms should be sought, as should the timing of symptoms (e.g., worse in the morning or progression over weeks to months). The presence or absence of sensory disturbances including numbness, burning, or tingling and any associated radiation of symptoms should be elicited and may indicate neurologic pathology. Prior therapies and their efficacies should also be noted.

Associated relevant medical history is important because various systemic illnesses may render the foot and ankle more susceptible to certain problems. Specifically, patients should be questioned about a history of diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, inflammatory arthritis, and neurologic conditions. Current medications and medical allergies should be noted. A prior surgical history—specifically prior foot and ankle procedures—is also helpful. Patients should also be questioned regarding a history of trauma. Prior adverse reactions to anesthetics should be noted in patients who are candidates for surgery.

History of tobacco use, specifically cigarette smoking, and alcohol use should be routinely obtained because they can significantly affect the outcomes of both surgical and nonsurgical therapies. Pending litigation and worker’s compensation claims may influence the diagnostic approach, the treatment plan, and ultimately the patient outcome.

History taking in the athlete deserves special mention as a thorough, focused history on injury mechanism, chronicity of symptoms, and compensatory mechanisms may provide important clues to the diagnosis. With acute injuries, details should be elicited, including the position of the foot or ankle relative to the body during injury; whether there was any particular sensation experienced including a pop, locking, or crunching; whether weight-bearing was possible immediately after the injury; and whether any reduction maneuvers had to be performed immediately after the injury. For chronic symptoms, athletes may be questioned on previous treatments; whether symptoms were initiated by a distant trauma, experienced only with athletic activity, or were exacerbated by external factors such as shoe wear or athletic pads. Precipitating athletic activity such as cutting, jumping, or running may also provide important clues.

INITIAL PRIMARY EXAMINATION

A systematic and reproducible primary examination should be performed on every patient to gather accurate and

complete objective information consistently. This overview may provide insight that may not be specifically related to the patient’s chief complaint. Following a reproducible primary survey, a more focused physical examination can be undertaken based on the patient’s complaints and other findings. By performing the same primary examination with each patient, critical omissions are avoided.

complete objective information consistently. This overview may provide insight that may not be specifically related to the patient’s chief complaint. Following a reproducible primary survey, a more focused physical examination can be undertaken based on the patient’s complaints and other findings. By performing the same primary examination with each patient, critical omissions are avoided.

Inspection and Observation

Shoe Wear

Inspection of the patient’s shoe wear can be valuable in various foot and ankle disorders and should not be omitted. Improper shoe wear and shoe size have been implicated as causative factors in various foot pathologies. Studies have demonstrated significant discrepancies between actual measured foot size and the patient’s perceived shoe size in certain populations. Furthermore, many patients will have an actual mismatch in shoe size between the right foot and left foot, which is often unaccounted for in footwear sizing.

Specific patterns of shoe wear may be observed:

An oblique as opposed to a transverse crease in the shoe’s forefoot may suggest hallux rigidus.

Scuffing of the toe box may indicate a drop foot.

A significant flatfoot deformity may result in broken medial shoe counter.

Excessive in-toeing or high-arched feet may create excessive lateral sole wear.

Standing Inspection

The remainder of the initial examination should proceed in a systematic manner, beginning with standing inspection of the foot and ankle from both anterior and posterior.

The patient’s legs should be exposed from the knee to the toes.

Overall alignment of the hindfoot and forefoot should be assessed as should any focal deformity.

The status of the longitudinal arch should be noted. Quantitative clinical indices of arch height have been described such as the Staheli, Chippaux-Smirak, truncated arch, and arch length indices; however, these are primarily for research purposes. Navicular height and normalized navicular height (normalized to foot length) have been shown to be the most accurate clinical measures of arch height.

The importance of the standing, weight-bearing examination cannot be overemphasized.

The foot structure may appear normal while sitting, but can be strikingly different when subjected to weight-bearing forces, as may be the case with hypermobile flatfoot deformity, flexible toe deformities, and hypermobile metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints.

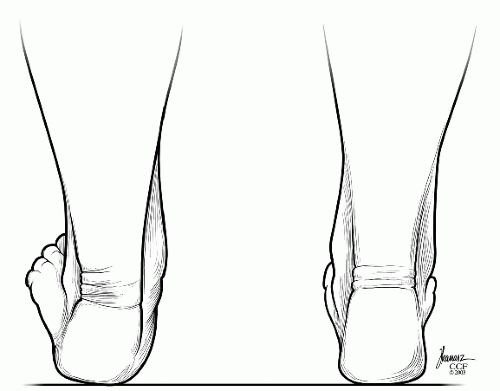

The “too many toes” sign is indicative of hindfoot valgus (Fig. 2.1).

Examination of gait is an essential part of the initial primary examination.

Observations should include assessment of any side-to-side asymmetry, ability to achieve a plantigrade foot, foot placement, and general flow of the heel strike, foot flat, toe-off progression as well as any avoidance patterns.

Single- and double-limb heel rises should be observed from behind the patient with the knees extended.

Side-to-side comparison is helpful in identifying pathology.

The inability to perform a single-limb heel rise or lack of symmetrical inversion of the hindfoot strongly suggests tibialis posterior tendon pathology (Fig. 2.2).

Seated Evaluation

Figure 2.2 Double heel rise test. Calcaneal inversion is normal on the right and absent on the left. (Reprinted with permission of the Cleveland Clinic.) |

The vascular evaluation includes palpation of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses.

The dorsalis pedis pulse is typically located between the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) and the extensor digitorum longus tendons, just proximal and lateral to the dorsal prominence of the first metatarsal base and medial cuneiform.

The posterior tibial pulse is palpable behind the medial malleolus, approximately one-third of the distance to the medial border of the Achilles tendon.

If pulses are weak or absent, a more comprehensive vascular evaluation is warranted, especially if surgery is being considered or if the patient has an open wound.

This evaluation may include pulse volume recordings with toe pressures or transcutaneous oxygen levels.

Skin and nail abnormalities are noted.

The presence of callosities may be indicative of regions of increased loading and are strong clues to abnormal foot mechanics.

Skin changes indicative of vascular disease, edema, and erythema are also noted.

A gross sensory evaluation helps prevent omission.

Light-touch sensation is evaluated grossly at the dorsal first and fourth web spaces (deep and superficial branches of the peroneal nerve) as well as the plantar surface of the foot (tibial nerve).

The medial and lateral aspects of the foot should also be briefly tested (saphenous and sural nerves).

More specific neurologic testing can be carried out later during the examination.

A brief range of motion examination with the patient in the sitting position may also provide insight into the presence of possible foot and ankle pathology.

Passive and active motions can be briefly and easily tested and should be part of the routine initial primary examination.

Normal passive ankle motion is approximately 20° of dorsiflexion to 50° of plantarflexion.

Subtalar motion can also be tested with the patient seated.

The examiner grasps the patient’s hindfoot with one hand while the other hand passively ranges the subtalar joint.

Normal range is approximately 15° in both subtalar inversion and eversion and is usually referenced as a fraction of the uninvolved side.

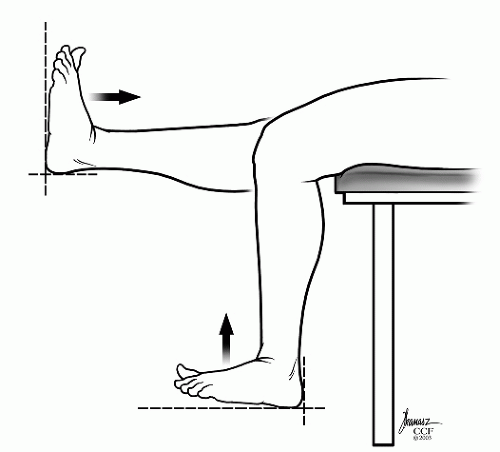

Ankle motion should be tested with the patient’s knee flexed to eliminate the effect of the gastrocnemius with the hindfoot held in neutral alignment to prevent dorsiflexion through the transverse tarsal joints (Fig. 2.3).

Forefoot abduction and adduction are tested with the hindfoot stabilized and passive force applied to the forefoot.

Normal range of forefoot motion is 20° of adduction and 10° of abduction.

Limitation of passive motion or pain with passive motion may indicate degenerative disease of a particular joint, prior fusion, or other pathology associated with that joint.

Active motion is grossly assessed by having the patient trace a circular pattern in the air with his or her toes. Alternatively, having patients walk on their toes and on the medial and lateral borders of their feet is also an indicator of whether a relatively normal range of motion is present.

Resistance strength testing should be performed in all major planes of active motion of the foot and ankle. This may provide insight into tendon, muscle, or nerve pathology.

Figure 2.3 Ankle dorsiflexion—knee extended and knee flexed. The hindfoot must be held in neutral alignment. |

This brief initial primary examination provides an excellent foundation for the remainder of a problem-focused physical examination. A basic assessment of the patient’s overall alignment, appearance, neurovascular status, range of motion, and strength can be obtained in a relatively short period without omission of any critical elements. Problem-focused physical examination can then proceed in a concise and orderly fashion.

FOCUSED EXAMINATION

Skin and Nails

The integrity of the soft-tissue envelope about the foot and ankle is important to note in any foot and ankle examination, especially if surgery is contemplated.

Prior surgical scars should be noted, as should the overall quality of the skin.

Trophic changes and hair loss may indicate peripheral vascular disease.

Dependent rubor is indicative of poor perfusion to the foot.

Venous insufficiency may manifest with pigmentation in the supramalleolar region.

Swelling, erythema, and increased skin temperature may be due to a number of causes including cellulitis, inflammatory arthritis, or neuropathic joints.

Ulcerations should be noted and characterized based on their location and appearance.

Callosities may form in regions subjected to higher than normal axial or shear load.

Although the function of callosities is to prevent blistering and protect deeper structures, they may become pathologic in that they paradoxically lead to increased pressure, especially in the neuropathic patient, frequently leading to ulceration.

Viral agents can cause plantar warts, which produce callosities that may be difficult to distinguish from mechanically induced callus. Trimming the overlying

callus usually reveals punctate black capillaries at the base of a wart. Pinching a wart usually causes significant pain, whereas it is relatively pain free with calluses.

Skin prints diverge around warts, whereas they course through a callosity.

Malignant melanoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of the foot.

Pedal lesions may be subtle and may present as a small area of subungal or epidermal discoloration. In the absence of recent trauma, a high index of suspicion is necessary to prevent delayed treatment or misdiagnosis.

Toenail disorders are often the cause of patient concern.

The closed environment of shoe wear can predispose the toenails to problems not seen in the hand. Eponychia, paronychia, and onychomycosis are common infectious processes seen in the toenail and are easily diagnosed by inspection alone.

Eponychia is an infection of the proximal nail fold, whereas paronychia refers to an infection of either the lateral or medial nail fold. These are commonly referred to as ingrown toenails.

Onychomycosis refers to a fungal infection of the nail and results in thickening, yellow-brown discoloration, discoloration, splitting, pitting, or ridging of the nail plate.

Pitting of the nail is also seen with psoriasis.

Bones and Soft Tissues

Bones

Because pain is frequently the patient’s chief complaint, localization and reproduction of the patient’s pain is invaluable in achieving a correct diagnosis. Much of the bony and soft-tissue anatomy of the foot and ankle is subcutaneous and relatively easy to palpate. With a thorough knowledge of the anatomy, localization of the painful structure is usually relatively straightforward.

The examination should be focused on the region of the patient’s complaint.

Asking the patient to point with one finger to the area of maximal pain is a simple way to begin a focused examination.

Pain can typically be reproduced by palpation of one or more bony or soft-tissue structures.

Bony landmarks that are easily palpable on the medial aspect of the foot include the first MTP joint, first metatarsal, medial cuneiform, navicular tuberosity, talar head, sustentaculum tali, medial malleolus, and medial calcaneus.

The first MTP joint is frequently associated with a bunion deformity or degenerative changes.

The navicular tuberosity is the primary attachment for the tibialis posterior tendon, and pain with palpation may indicate insertional pathology.

Avascular necrosis of the navicular or stress fracture may lead to tenderness.

The talar head can be more prominent in a pes planus deformity.

The medial malleolus is easily palpable and is the medial buttress for the tibiotalar joint.

The sustentaculum tali is located approximately one fingerbreadth below the medial malleolus. It may not be palpable, but it is important in that it serves as the attachment for the spring ligament and provides support for the talus.

Bony landmarks that are easily palpable on the lateral aspect of the foot include the fifth MTP joint, the fifth metatarsal, base of the fifth metatarsal, the cuboid, lateral calcaneus, including the anterior process and peroneal tubercle, lateral malleolus, and the talar dome and neck.

The base of the fifth metatarsal provides the insertion for the peroneus brevis tendon, and tenderness could indicate insertional pathology or a fracture.

The peroneal tubercle is palpable on the lateral aspect of the calcaneus below the lateral malleolus and serves as the point where the peroneal tendons (longus and brevis) separate as they turn around the lateral calcaneus.

The lateral malleolus provides a lateral buttress to the ankle joint.

It extends further distally than the medial malleolus and slightly posteriorly, allowing the ankle mortise to occupy a position of approximately 15° of external rotation relative to the long axis of the tibia.

It is susceptible to fracture.

The talar dome is palpable just anterior to the lateral malleolus with the foot held in plantarflexion and slight inversion.

Tenderness here may suggest an ostechondral lesion, fracture, or synovitis.

The sinus tarsi region is the soft spot that is easily palpable on the lateral aspect of the hindfoot and is the site most specific for subtalar joint pathology.

Deep palpation may reveal tenderness at the anterior process of the calcaneus, a potential site of fracture or arthrosis.

The lateral process of the talus can be palpable and may be a site of injury (snowboarder’s fracture).

The lateral neck of the talus may also be palpable in some patients. Areas of edema, tenderness, or pain should be noted and deep palpation should be applied on the lateral aspect of the talar neck. If pain is elicited, further imaging with CT or MRI should be obtained to rule out an occult fracture if there is a history of trauma. Up to 39% of ankle and midfoot fractures may be missed on initial examination and radiographic evaluation. Palpation of the posterior aspect of the foot is performed with the patient seated.

Grasping the calcaneus and applying gentle compression may elicit pain indicative of a calcaneal stress fracture.

The retrocalcaneal bursa can be palpated with the thumb and fingers in the depressions adjacent to the Achilles tendon.

The medial tubercle of the calcaneus is palpable on the medial plantar surface and serves as the attachment for the abductor hallucis and flexor digitorum brevis, and is a common source of heel pain in adults.

Tenderness to palpation centrally along the plantar surface of the calcaneus may indicate a periostitis.

The posterior aspect of the calcaneus may be a site of tenderness in children as a manifestation of an

apophysitis (Sever disease) or insertional Achilles tendinitis in adults.

The bony landmarks to examine on the plantar surface of the foot include the sesamoid bones and the metatarsal heads.

Deep palpation at the plantar surface of the first MTP joint reveals two palpable sesamoid bones.

These sesamoid bones lie within the substance of the flexor hallucis brevis tendons and help distribute weight borne by the first ray, as well as provide mechanical advantage for the flexor hallucis brevis tendons.

Tenderness may reveal a sesamoiditis, stress fracture, or avascular necrosis.

Their location may be altered with hallux valgus.

The lesser metatarsal heads are easily palpable on the plantar surface of the forefoot and may be tender if poorly padded or with MTP synovitis.

Callosities may be present in areas of overuse.

Tenderness at the metatarsal heads can be due to avascular necrosis (Freiberg disease).

Soft Tissues

Palpation of the soft tissues should likewise proceed in a systematic and focused fashion based on the patient’s complaints.

At the forefoot medially, the first MTP joint is a common source of pathology, especially if hallux valgus deformity is present.

Bursal formation at the first MTP joint may be present and may be tender to palpation at the medial aspect of the joint.

Gouty tophi may be present and painful.

Callus formation and tenderness may be present in a longstanding pes planus deformity.

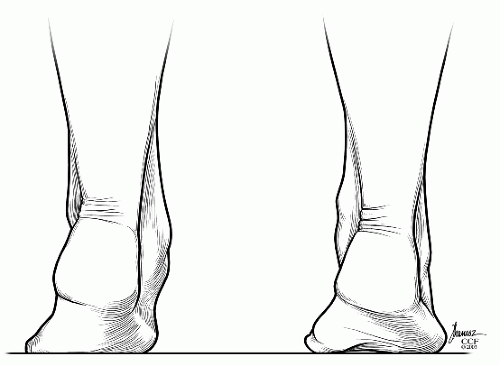

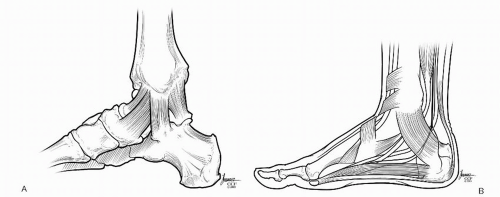

On the medial side of the hindfoot and ankle, the deltoid ligament is typically palpable beneath the medial malleolus (Fig. 2.4).

The soft-tissue depression between the medial malleolus and the Achilles tendon includes the tibialis posterior tendon, flexor digitorum longus tendon, neurovascular bundle (posterior tibial artery and tibial nerve), and flexor hallucis longus tendon.

The tibialis posterior tendon is most readily palpable from behind the medial malleolus to its insertion on the navicular tuberosity.

The flexor hallucis longus is typically not palpable because of its deep location.

A Tinel sign is present if paresthesias along the distal course of the tibial nerve are elicited by tapping on the nerve, possibly indicating the presence of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

On the dorsum of the foot, the tibialis anterior (TA) tendon is easily palpable along the medial aspect of the ankle, extending to its insertion at the medial base of the first metatarsal.

The EHL tendon is lateral to the TA tendon and can be traced distally along the first ray.

Tenderness may indicate tendon pathology.

A lump beneath the extensor retinaculum along the ankle may represent a ruptured anterior tibialis tendon.

Along the lateral aspect of the ankle, the three primary lateral ankle ligaments—the anterior talofibular ligament, posterior talofibular ligament, and calcaneofibular ligament—are palpated (Fig. 2.5).

Tenderness may indicate injury to the lateral ligaments.

The peroneal tendons are palpable along the lateral aspect of the ankle.

Distally, the head of the fifth metatarsal may be a site of bursal formation resulting from a bunionette.

The Achilles tendon is the largest tendon in the human body and is palpable in the subcutaneous hindfoot down to its insertion into the calcaneus.

A defect may be palpable in cases of rupture.

Nodularity may be present and tender in cases of chronic inflammation or tendinosis.

The retrocalcaneal and calcaneal bursae may be tender on the anterior and posterior surfaces of the Achilles tendon, respectively.

Figure 2.4 Medial view of the ankle. (A) Deep layer—deltoid ligament. (B) Superficial layer—retinacular/tendon structures. (Reprinted with permission of the Cleveland Clinic.)

Figure 2.5 Lateral view of the ankle. (A) Deep layer—lateral ligaments. (B) Superficial layer—retinacular/tendon structures. (Reprinted with permission of the Cleveland Clinic.)

The plantar fascia is also palpable from its insertion at the medial tubercle of the calcaneus and along its course on the plantar medial surface of the foot. Tenderness may indicate inflammation, and nodularity may be present with plantar fibromatosis.

Nerves

Certain complaints, symptoms, and concurrent medical conditions mandate a more thorough neurologic examination than is done in the initial primary assessment.

Peripheral neuropathy due to a systemic process such as diabetes mellitus may be present.

Decreased or absent sensation is present symmetrically in a stocking distribution.

Absence of the Achilles reflex and decreased vibratory sensation may indicate peripheral neuropathy.

The ability to detect a 5.07 (10-g) Semmes—Weinstein monofilament is typically indicative of the presence of protective sensation.

More specific peripheral nerve pathology such as nerve entrapment or a surgical or traumatic lesion should be sought in cases of neurologic complaints.

The common peroneal nerve may become entrapped at the fibular neck, producing symptoms of numbness on the dorsum of the foot and weakness in foot and toe dorsiflexors.

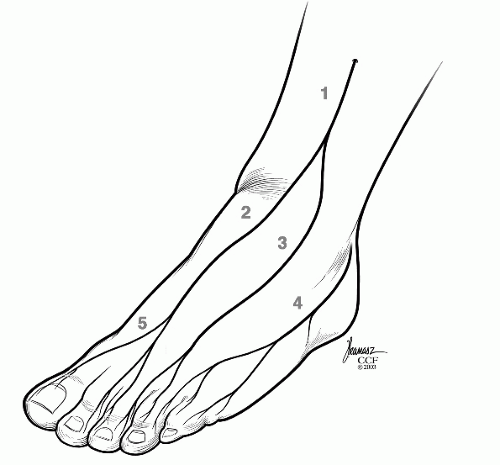

The superficial branch of the peroneal nerve can become entrapped just anterior to the fibula as it penetrates the superficial fascia approximately 8 to 10 cm above the ankle joint (Fig. 2.6).

Percussion along the course of the nerve may elicit paresthesias or pain.

The posterior tibial nerve and its branches may become entrapped in the tarsal canal posterior to the medial malleolus (Fig. 2.7).

Patients typically complain of burning, aching, or numbness on the plantar surface of the foot.

Tenderness and a positive Tinel sign with propagation of paresthesias with percussion aid in the diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Isolated peripheral nerve injuries are often the result of trauma, sometimes the consequence of a prior surgical procedure.

The sural nerve is at risk with lateral hindfoot approaches resulting in numbness of the lateral border of the foot.

Figure 2.7 Nerves—plantar medial view. (1) Tibial nerve; (2) medial plantar nerve; (3) lateral plantar nerve; (4) medial calcaneal nerve; (5) medial plantar hallucal nerve. (Reprinted with permission of the Cleveland Clinic.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access