Degenerative Joint Disease of The Midfoot and Forefoot

Chad B. Carlson

Michael E. Brage

11.1 MIDFOOT ARTHRITIS

A variety of forms of arthritis affect people of all ages and have significant impact on employment, activities of daily living, and quality of life. It is estimated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States and affects nearly 21 million people. The commonest form of arthritis encountered is osteoarthritis (OA), but there are more than 100 other rheumatologic conditions that can cause arthritis-related disability in every age group, ethnicity, and sex.

As physicians, we must be prepared to not only manage the chronic disabilities that fail conservative care but also recognize systemic disease that presents as an isolated foot problem such as the swollen forefoot that on careful examination reveals peripheral symmetric joint involvement as in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

This chapter encompasses the midfoot and forefoot arthritides, such as primary OA and secondary posttraumatic arthrosis as well as the related topics of hallux rigidus, forefoot RA, crystal-induced arthropathy, and turf toe. The general format will focus stepwise on epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and classification. We then turn to diagnosis clinically and radiographically, giving algorithms when needed. Finally, treatment will be discussed by pinpointing surgical versus nonsurgical modalities, the indications, outcomes, and follow-up of each.

INTRODUCTION

Arthritic disease of the midfoot includes primary degenerative arthritis (OA), secondary posttraumatic arthritis, inflammatory arthritidies (such as RA), seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and crystal-associated arthritis, which includes gout and pseudogout (chondrocalcinosis). The most common forms, primary degenerative arthritis and posttraumatic arthritis of the midfoot, will be the emphasis of this section.

The ability to understand, diagnose, and appropriately treat the midfoot is greatly facilitated by understanding the articular divisions, or columns, of the midfoot, including the following:

Medial—the first metatarsocuneiform joint

Central (middle)—the second and third metatarsocuneiform joints and the intercuneiform joints

Lateral—the cubometatarsal joints.1

Some authors combine the medial and middle columns into the medial column as the three tarsometatarsal (TMT) joints are relatively immobile. These columns are enveloped in a stout soft-tissue complex of various ligaments, and the bony architecture of the three cuneiforms and the cuboid forms the transverse arch of the midfoot (Fig. 11.1.1). The significance of the columnar division of the midfoot relates to the amount of motion occurring at each of these articular surfaces. Studies have shown that about 10° of midfoot motion occurs in the sagittal and rotational planes at the lateral column and much less motion in the medial and middle columns. In one cadaver study, it was shown that with increased loads, the medial and middle columns showed significant increases in articular contact forces, whereas the lateral column did not show increased contact forces despite loading up to twice the body weight.2 Thus, the increased motion and decreased injury incidence occurring in the lateral

column are two important reasons why it is much less involved in arthritis than the other two columns. For this reason and owing to the importance of lateral column motion to foot biomechanics, preservation of lateral motion during midfoot fusions is beneficial and much less debilitating.

column are two important reasons why it is much less involved in arthritis than the other two columns. For this reason and owing to the importance of lateral column motion to foot biomechanics, preservation of lateral motion during midfoot fusions is beneficial and much less debilitating.

Stabilization of the midfoot is based on the ligamentous and bony integrity of the second TMT joint. Lisfranc ligament, the interosseous ligament that runs obliquely from the second metatarsal base to the medial cuneiform, is the largest midfoot ligament and along with the second plantar ligament (intermetatarsus ligament between the second and the third metatarsals) is the strongest ligament in the midfoot.3 The Lisfranc joint (transverse TMT joint) provides the primary stabilization to the midfoot and is the keystone in creating a “Roman arch-like” effect that resists midfoot collapse (Fig. 11.1.1). As a consequence, small disruptions (displacement and/or alignment changes) to this joint can result in considerable loss of articular contact surface area. Indeed, even subtle injuries with small amounts of displacement or ligamentous disruption to this region can affect midfoot stability and biomechanics, thus predisposing to posttraumatic degenerative changes.

PATHOGENESIS

Epidemiology

OA is a slowly developing degenerative disease affecting many joints of the body. As the most common musculoskeletal disorder worldwide, it exacts a tremendous toll socially and economically in developed countries, establishing itself as the major cause of morbidity in these nations. OA prevalence increases significantly with age and correlates with obesity and high levels of activity or impact loading on the foot. However, secondary arthritis of the midfoot, often the result of previous trauma, is more common than primary OA and can be induced by various injuries. The most common posttraumatic injury leading to midfoot arthritis is injury to the Lisfranc joint, but others include navicular and/or cuboid fracture dislocations as well as metatarsal fractures and ligamentous injuries to the TMT complex.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

In the midfoot TMT complex, arthritis is typically either a primary arthrosis of the TMT complex or a secondary

degenerative arthrosis most commonly because of previous trauma or osteochondritis dessicans. Primary degenerative arthrosis (i.e., OA) of the midfoot, regardless of the specific joints affected, generally occurs in older patients and, owing to the gradual nature of disease progression, is typically more advanced and produces greater deformity than that of posttraumatic arthrosis (unless severe). This is especially true when multiple joints are involved, but OA can be present with little deformity when a single joint is involved. A thorough evaluation of associated conditions should always be done including an evaluation to determine whether a gastrocnemius and/or soleus contracture is present.

degenerative arthrosis most commonly because of previous trauma or osteochondritis dessicans. Primary degenerative arthrosis (i.e., OA) of the midfoot, regardless of the specific joints affected, generally occurs in older patients and, owing to the gradual nature of disease progression, is typically more advanced and produces greater deformity than that of posttraumatic arthrosis (unless severe). This is especially true when multiple joints are involved, but OA can be present with little deformity when a single joint is involved. A thorough evaluation of associated conditions should always be done including an evaluation to determine whether a gastrocnemius and/or soleus contracture is present.

Posttraumatic midfoot arthrosis is the most common etiology of arthrosis in the midfoot. Both subtle and severe traumatic injuries can result in significant degenerative midfoot arthrosis. Three predisposing factors that will lead to joint degeneration include (a) articular cartilage injury, (b) joint displacement with medial longitudinal arch collapse, and/or (c) persistent joint malalignment. Usually there is a history of high-energy traumatic injury, but even low-energy trauma with Lisfranc complex compromise, which may have been missed or overlooked, can result in significant posttraumatic arthrosis. Along with Lisfranc injuries, other injuries predisposing to midfoot arthrosis are multiple metatarsal fractures, posterior tibial tendon injuries resulting in medial longitudinal arch collapse, and intercuneiform instabilities. Lateral column arthrosis can result from cuboid compression or “nutcracker” fractures. Understanding of the complex anatomy of this region and how it is stabilized is vital to both diagnosis and treatment of primary and secondary arthroses of the midfoot.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Features

As with arthritis in general, the commonest complaint of midfoot arthritis is pain. Patients may also complain of shoe wear problems owing to bony prominences or deformity. Physical examination should reveal tenderness and often limited motion at these painful areas. A standing and sitting examination of both feet should be included to determine whether deformity, motion limitations, neurovascular compromise, or focal tenderness is present and to what extent. A weight-bearing examination is essential to determine the degree and extent of deformity. In both primary and posttraumatic midfoot arthroses, deformity and swelling may be present and the characteristic flatfoot appearance of pronation, dorsiflexion, and abduction seen (Fig. 11.1.2). In general, midfoot pain is due to articular surface injury/wear/inflammation with normal joint movement and no obvious instability or abnormal movement at a joint—with or without articular surface changes. Ligamentous injuries at the Lisfranc joint often result in the latter (abnormal movement), whereas, at least initially, primary arthrosis typically results from the former (articular surface changes). When it is difficult to assess exact origins of pain, localized injections have been advocated. These may be difficult to interpret owing to the different compartments of the foot, the diffusion into or from the joint where the anesthetic is injected, and the plane in which it enters. However, when anesthetic injections are assisted by radiography and result in prolonged pain relief, they can be extremely valuable in determining the joint that is the source of pain.4,5

Radiologic Features

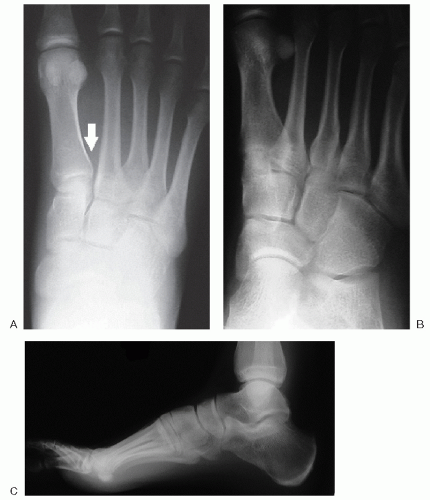

Standing images of both feet in the anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and 30° oblique planes are most helpful. In assessing the degree of deformity, comparison with non—weight-bearing views and with the other foot is useful, as is evaluating for loss of talar head coverage by the navicular. Joint space narrowing and subchondral bone sclerosis may be seen (Fig. 11.1.3). Although significant bony displacement or arthrosis of the midfoot articulations may be easily seen, subtle injuries or single joint involvement may be difficult to appreciate on plain radiographs. Furthermore, physical examination findings and plain radiographic appearance may not be easily correlated with the significant painful symptoms of arthritic disease. Therefore, some advocate CT or bone scan for further determination of the specific location and extent of arthrosis in the midfoot, especially in cases of preoperative planning. This, however, remains controversial, and CT results should be evaluated for consistency with plain radiographs, examination, and intra-operative findings.

In the presence of posttraumatic arthrosis, it is still important to decipher whether the Lisfranc midfoot injury exists. Careful evaluation of weight-bearing X-rays should include colinearity of the medial aspect of the middle cuneiform with the second metatarsal on an AP view; the medial border of the cuboid should be colinear with the medial aspect of the fourth metatarsal on the oblique view; and any dorsal displacement of the metatarsal complex on the lateral view is indicative of a ligamentous injury. Further evaluation can include abduction/pronation and adduction/supination stress radiographs of the foot, contralateral films for comparison, and perhaps CT scan, bone scan, or MRI

of the affected foot. Chronic Lisfranc injuries, possibly missed after a previous injury, often present only with painful gait and minor tenderness and might be identified only by stress radiographs that reveal widening between the first and the second metatarsals. Both weight-bearing and stress radiographs may be more representative and better tolerated by using an ankle block anesthetic. These further studies can be helpful in the posttraumatic setting to evaluate the extent of medial, middle, and lateral column arthroses, especially when operative intervention is being considered.

of the affected foot. Chronic Lisfranc injuries, possibly missed after a previous injury, often present only with painful gait and minor tenderness and might be identified only by stress radiographs that reveal widening between the first and the second metatarsals. Both weight-bearing and stress radiographs may be more representative and better tolerated by using an ankle block anesthetic. These further studies can be helpful in the posttraumatic setting to evaluate the extent of medial, middle, and lateral column arthroses, especially when operative intervention is being considered.

TREATMENT

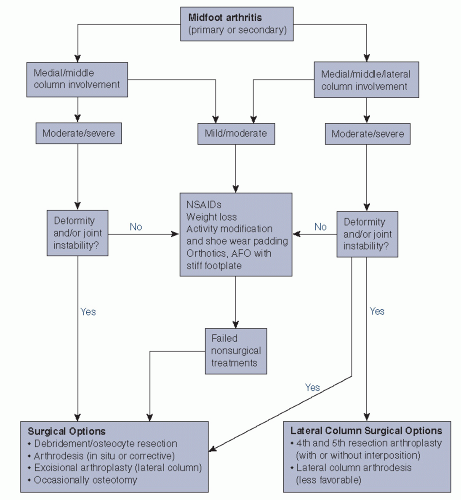

The options for the treatment of primary or secondary degenerative arthrosis in the midfoot depend on the patient’s pain and activity levels (Algorithm 11.1.1). Nonoperative treatment may alleviate enough pain to allow for increased levels of activity and function for a variable time while not being overly restrictive. Decisions to operatively intervene should come after nonoperative measures have been tried and pain/loss of function remains unacceptable.

Nonoperative Treatment

Nonsurgical management should be focused on relieving pain and providing midfoot stability and support. This is especially valuable to the osteopenic patient and should begin early in the course when arthrosis of the midfoot or forefoot is suspected. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) often help, as do weight loss and activity modifications, especially in conjunction with supportive shoe wear. Bony osteophytes often protrude around the joint and into soft tissues, needing pressure relief by padding or stretching of the overlying shoe. Orthotic devices can provide padding, with added support for the longitudinal arch and relief of some pain at the metatarsal head. However, when significant deformity is present, arch support is often not well tolerated. An ankle—foot orthosis (AFO) with a stiffened foot plate may also provide some relief. In general, orthotics that decrease motion of painful degenerative joints will contribute significantly to pain control. Dorsal osteophytes may be especially troublesome, but padding and modifying shoe wear can decrease pressure in that region to relieve some pain.

Surgical Considerations

Surgical indications for patients with primary and secondary midfoot arthroses include instability and/or continued pain that affects activities of daily living, despite attempts at nonoperative management. Although debridement and resection of osteophytes—especially when skin irritation or nerve impingement is occurring—are useful and can bring symptomatic relief, the main surgical options for degenerative arthrosis generally involve arthrodesis, excisional arthroplasty, and sometimes osteotomy of the involved joints. In general, medial and middle column midfoot arthrodesis is the preferred surgical modality for arthrosis in these regions, whether the cause is primary degenerative disease, posttraumatic arthrosis, or inflammatory arthritis in particular (Fig. 11.1.4). The operative management of lateral column midfoot arthrosis is discussed later.

In Situ Fusion

When deformity is not present, in situ fusion is indicated and should include rigid internal fixation of every involved joint. Surgical approaches vary, but in general the first TMT joint can be approached dorsally or dorsomedially. When approaching the second and third TMT joints or the

fourth and fifth TMT joints, longitudinal incisions between the second and the third metatarsals or the fourth and the fifth metatarsals, respectively, can be used. Following the approach, the joint should be exposed and all articular cartilage removed. Underlying subchondral bone should be perforated using an osteotome or multiple drill holes. For fixation and compression, standard lag screw techniques can be utilized using 3.5-mm fully threaded screws in a number of screw configurations crossing the joint involved. Some surgeons also use dorsal plates—locked or unlocked (Fig. 11.1.4). Fixation of intercuneiform or intermetatarsal joints can be achieved often in a medial to lateral fashion. Supplemental bone grafting is usually not necessary but can be used either with local bone graft or from drillings. Lateral midfoot motion should be preserved if not affected by painful arthrosis, and in general the cubometatarsal joints infrequently require arthrodesis. Naviculocuneiform joint fixation can be accomplished in medial to lateral fashion as well and may be facilitated by joint release. Fixation at each level should consider the anatomic positions and weight-bearing function of each TMT (and even metatarsophalangeal [MTP]) joint. For example, first metatarsocuneiform joint arthrodesis accomplished by fixation and shortening of the medial column may require first metatarsal plantarflexion to distribute forces evenly for weight-bearing.

fourth and fifth TMT joints, longitudinal incisions between the second and the third metatarsals or the fourth and the fifth metatarsals, respectively, can be used. Following the approach, the joint should be exposed and all articular cartilage removed. Underlying subchondral bone should be perforated using an osteotome or multiple drill holes. For fixation and compression, standard lag screw techniques can be utilized using 3.5-mm fully threaded screws in a number of screw configurations crossing the joint involved. Some surgeons also use dorsal plates—locked or unlocked (Fig. 11.1.4). Fixation of intercuneiform or intermetatarsal joints can be achieved often in a medial to lateral fashion. Supplemental bone grafting is usually not necessary but can be used either with local bone graft or from drillings. Lateral midfoot motion should be preserved if not affected by painful arthrosis, and in general the cubometatarsal joints infrequently require arthrodesis. Naviculocuneiform joint fixation can be accomplished in medial to lateral fashion as well and may be facilitated by joint release. Fixation at each level should consider the anatomic positions and weight-bearing function of each TMT (and even metatarsophalangeal [MTP]) joint. For example, first metatarsocuneiform joint arthrodesis accomplished by fixation and shortening of the medial column may require first metatarsal plantarflexion to distribute forces evenly for weight-bearing.

Corrective Fusion

When deformity is present, corrective fusion using bone graft and soft-tissue lengthening or shortening is indicated. The extent of deformity required for correction will vary, but in general, any deformity with greater than 2 mm or 15° of displacement should be corrected. For midfoot medial column deformity, bony resection is often necessary and fixation can be achieved by interfragmentary screw fixation after meticulous joint preparation. Plating the medial column may be helpful as well, especially in osteoporotic bone, or if screw purchase is poor. More important, the lateral column may require lateral soft-tissue lengthening (especially the peroneus brevis tendon) to achieve appropriate medial column deformity correction. Kirschner wires (K-wires), laminar spreader, or external fixator on the lateral column can assist in achieving adequate reduction/correction as well.

Lateral Column Arthrosis

The most common long-term complication of midfoot arthrodesis is the development of symptomatic arthritis in adjacent motion segments, albeit the midfoot has a lower incidence of this than other areas of the foot and ankle.6 Other causes of lateral column midfoot arthrosis include Lisfranc complex injuries as well as degenerative and inflammatory arthritidies, isolated lateral midfoot trauma (cuboid “nutcracker” type fracture) and base of fifth metatarsal fracture sequelae.7 TMT joint arthrodesis for posttraumatic arthrosis is well reported where the incidence of lateral column symptoms is fairly small (from 6% to 25%).1,8,9 In the study by Komenda et al.,1 2 of 32 patients were symptomatic enough to require lateral column fusion. This study, as well as those by Mann et al.8 and Sangeorzan et al.,9 did not reveal complications specific to lateral column fusions but suggested that an alternative was “welcomed” and that appropriate diagnosis of lateral column arthrosis as the true source of pain was imperative. Indeed, the majority of midfoot motion is through the cuboid-fourth/fifth metatarsal articulation, and fusion of this region can be disabling, leaving the patient with a very stiff foot.

An alternative to lateral column arthrodesis is tendon arthroplasty for basal fourth and fifth metatarsal arthritis, as proposed by Berlet and Anderson.7 In this study, 12 patients who failed nonoperative treatment for lateral column arthrosis underwent resection arthroplasty of the base of the fifth or fourth and fifth metatarsals with tendon interposition. Average follow-up was 25 months, and patients were evaluated with the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) clinical midfoot scale— a visual analogue scale for pain and disability perception and a satisfaction index. The AOFAS score was 64.5, and pain scores improved an average of 35%, whereas disability scores improved by 10%. Overall, the operation was deemed satisfactory in 75% of patients. All patients had lateral column motion preservation, although the amount of motion was not used as an assessment tool as the authors felt there was too much inaccuracy in its measurement and was difficult to reproduce in the clinical setting. The authors believe that lateral column TMT resection arthroplasty “is an effective salvage operation when lateral column midfoot arthritis is confirmed by differential injection and nonoperative measures have provided inadequate relief.”7 This procedure gives the surgeon a motion-sparing alternative for lateral column arthritis and stresses the importance of truly identifying the lateral column as the source of a patient’s arthritic complaints by differential injection. Indeed, patients with higher postoperative AOFAS scores were statistically more likely to have had a positive differential anesthetic injection preoperatively.7 This is important because lateral column arthritic changes identified on radiographs do not always lead to lateral midfoot pain or functional impairment.1,10

Technique. Following local (ankle block), regional or general anesthesia, limb exsanguination and tourniquet placement, a dorsolateral incision is made paralleling the long axis of the foot. Center the incision on the fourth metatarsocuboid joint, taking care to avoid sural nerve injury. Expose the fourth toe long extensor tendon as well as the peroneus tertius tendon—the latter should be released proximally and retracted out of the wound. The long extensor tendon of the fourth toe can be used when this tendon is absent. Open the fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joint capsule dorsally and debride the joints. Debridement should be carried down to subchondral bone distally to create an approximately 1-cm space (proximal-distal) while maintaining the plantar and medial ligamentous supports as well as the lateral capsule. Insert the rolled up peroneus tertius tendon graft into the joint(s).7 Joint alignment in approximately neutral can be maintained by 0.062-in K-wire insertion from distal-lateral to proximal-medial and through the tendon graft. If inadequate tendon is available, an allograft or synthetic ball can be used for interposition.

Postoperative care comprises rigid splint placement in the operating room and non-weight bearing for 6 to 8 weeks, at which time the K-wire is removed. Weight bearing as tolerated commences at 6 to 8 weeks, and the patient is kept in a walker boot or short leg cast for four additional weeks. A shoe is then used after this time. Concomitant procedures may modify this regimen.

RESULTS AND OUTCOMES

Patients undergoing nonoperative treatment have a variable course, depending on the location, extent, and duration of arthrosis of the midfoot. A significant proportion will go on to require midfoot arthrodesis and/or osteophyte resection. Studies indicate that the outcome of midfoot arthrodesis for primary and posttraumatic degenerative arthrosis is good, with one study showing a 93% satisfaction rate and 98% union rate (176 of 179 joints) in 40 patients followed for an average of 6 years.8 Deformity correction was approximately 8° in this study. Another study by Komenda et al.1 in 32 patients requiring midfoot arthrodesis for posttraumatic arthrosis demonstrated only one asymptomatic nonunion and substantial improvement in the clinical foot score. Extent or location of the arthrodesis, patient age, or need for revision surgery did not have a significant effect on outcome in this study. Malunion occurred in 7 of the 32 patients. The malunions involved second metatarsal plantarflexion in all seven patients and in addition, third or first metatarsal plantarflexion in four patients. Surgical correction for these malunions was required only in two patients and involved dorsal closing-wedge osteotomies.

11.2 FOREFOOT ARTHRITIS

INTRODUCTION

Arthritis typically affecting the forefoot includes OA, RA, the seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and the crystal-induced arthritidies. Some of these arthritic conditions have a predilection for the forefoot (e.g., RA, gout). The focus of this section will be on hallux rigidus, RA of the forefoot, gout, pseudogout, and turf toe injuries, a predisposing factor for first MTP joint arthrosis.

HALLUX RIGIDUS

PATHOGENESIS

Epidemiology

Hallux rigidus is a painful arthritic condition of the first MTP joint characterized by restricted dorsiflexion and dorsal osteophytes. Normal range of motion is approximately 30° of plantarflexion and nearly 100° of dorsiflexion with approximately 60° of dorsiflexion required for normal gait and activities of daily living. It is generally seen in a younger population of patients than with other conditions of arthritis, and the incidence is estimated to be 1 in 45 of the adult population aged 60 years or older. However, this disorder occurs in two age groups. The much less common subset of patients affected are adolescents, with an incidence of 1 in 4,500. The adolescent form is characterized by localized osteochondral lesions rather than the more generalized diffuse arthrosis seen in the adult form.

Etiology

The precise etiology of hallux rigidus is still unknown; however, many authors have noted predisposing factors that have been proposed to cause increased stress across the hallux MTP joint. These include flat metatarsal head, a long first metatarsal, a dorsiflexed first metatarsal, improper shoe wear, a long slender foot, congenital deformities, gastrocnemius contracture, pes planus, and a pronated foot. Besides these factors, the degenerative process can be caused by trauma, accumulated microtrauma secondary to eccentric loading, systemic diseases, osteochondritis dissecans, turf toe injuries, or infection. Even with this list of predisposing conditions and anatomic factors, many cases have an unknown cause.

Pathophysiology

In understanding first MTP joint pathology, it is important to recall that the first MTP joint is cam shaped with a convex metatarsal head and concave proximal phalangeal base. Stability comes mainly through strong medial and lateral collateral ligaments, a thick plantar plate, and metatarsosesamoid suspensory ligaments. Motion at the first MTP joint is mainly dorsiflexion (with less plantarflexion) and functions by a sliding action along the metatarsal head.

The pathology of hallux rigidus, whatever the cause, is the result of an imperfect ball and socket joint and altered joint kinematics leading to early compressive forces during dorsiflexion and subsequent arthrosis.11 The degenerative process begins with synovitis and associated articular degeneration of the dorsal metatarsal head. Impingement of the base of the proximal phalanx on the dorsal metatarsal head occurs with forced dorsiflexion leading to chondral or osteochondral injuries of the articular cartilage. Cartilage erosions and dorsal and lateral osteophyte formations follow. The osteophytes become larger and more prominent thus restricting range of motion. The mechanical impingement dorsally causes jamming instead of gliding of the proximal phalanx on the metatarsal head. The pain associated with this destructive joint process is secondary to synovitis, motion of the arthritic joint, and dorsal impingement of the

osteophytes with dorsiflexion. Stretching in plantarflexion of the synovium, digital nerves and capsule over the osteophytes also causes irritation and produces pain.

osteophytes with dorsiflexion. Stretching in plantarflexion of the synovium, digital nerves and capsule over the osteophytes also causes irritation and produces pain.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Features

Hallux rigidus usually presents with an insidious onset of a painful, stiff, and swollen first MTP joint without any history of trauma. Most often the pain is activity related and progresses to a point that makes shoe wear difficult, especially those with elevated heels. Occasionally patients with acute osteochondral lesions may remark about a clicking or catching sensation with range of motion. It is important to elicit from the history not only the hallmarks of this condition, pain, loss of dorsiflexion, and increased bulk of the first MTP joint but also the limitations of the patient’s activity level. This will help guide treatment recommendations.

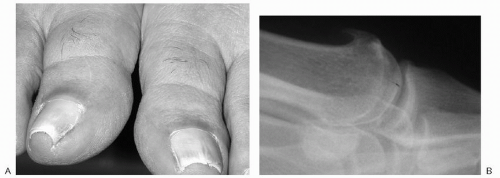

Physical examination findings can vary with the severity of the disease but the characteristic finding is restricted active and passive dorsiflexion, which reproduces the patient’s pain. This dorsal impingement syndrome is caused by marginal osteophytes—typically present dorsally and, less commonly, laterally. The first MTP joint is usually tender to palpation about the dorsal prominence and the dorsolateral ridge. There may also be dorsal skin changes over a prominent osteophyte (Fig. 11.2.1A). The first MTP joint can demonstrate varying degrees of swelling, which can be both seen and palpated. Neuritic signs, pain, and paresthesias with percussion along the dorsal medial and lateral digital nerves to the great toe can also be a finding on physical examination. Gait abnormalities, such as supination of the forefoot and walking on the lateral border of the foot to avoid pushing off through the first MTP joint, occur as a late finding because normal walking requires only 15° of dorsiflexion.

Patients with osteochondral injuries do not have bony proliferative changes until late. Early physical examination findings with osteochondral lesions can include clicking and pain with passive range of motion and compression across the first MTP joint. This may be relieved with joint distraction during range of motion.

Radiologic Features

Radiographic evaluation should comprise weight-bearing AP, lateral, and oblique views of the foot. These views are used to evaluate the degree of joint space narrowing. The AP view is also useful for evaluating the presence of medial or lateral osteophytes and is the best view to assess osteochondral lesions. The lateral view demonstrates the presence of dorsal osteophytes and the degree of impingement as well as the presence of any loose bodies (Fig. 11.2.1B). The oblique projection can show flattening of the metatarsal head and can also be useful for assessing the amount of joint space remaining if the joint space is obscured by dorsal osteophytes on the AP view. Other radiographic modalities are seldom indicated, but occasionally a bone scan or MRI will detect early degenerative changes or an osteochondral defect before any plain radiographic evidence can be seen.

Classification

Classification schemes based on plain radiographic findings have been developed. However, radiographic images can range from totally normal to severe joint destruction, and the degree of radiographic involvement of the first MTP joint does not necessarily correlate with the degree of symptoms. One such classification system comprises three grades: grade I—minimal to no joint space narrowing with dorsal osteophytes, grade II—more extensive narrowing with only the plantar joint space preserved, and grade III—complete joint space narrowing and severe arthrosis.12 The utility of this classification system in developing treatment algorithms is debatable owing to poor correlation between radiographic involvement and symptom level. Another system includes a grade IV, where in addition to complete loss of joint space, the patient has pain throughout the MTP joint range of motion.

TREATMENT

Treatment for hallux rigidus is based on the patients’ complaints, age, and degree of interference with their activity requirements. Conservative care comprises mainly orthotic devices directed at preventing and relieving symptoms by relieving stress across the first MTP joint. Shoe modifications must provide a wide/deep toe box to accommodate the increased bulk of the arthritic joint and provide a rigid rocker sole to diminish joint motion. For work shoes, a stiff-soled shoe can be used, and for athletics, a rocker-sole insert across the MTP joint can be used with a sneaker. Occasionally a rocker bottom sole, metatarsal bar, or steel-shanked shoe can be tried, but the cumbersome nature of these orthotic devices has a low degree of patient acceptance. Although orthotics can be used to stiffen the sole and decrease motion, they also occupy space within the toe box. This diminished room in the toe box can aggravate symptoms, and therefore, if these devices are used, the shoe must be large enough to house the enlarged MTP joint as well as the orthotic. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, both oral and transdermal, can also be used to relieve symptoms, and intra-articular steroid injections can provide temporary relief in acute flare-ups.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree