122 Musculoskeletal Syndromes in Malignancy

Musculoskeletal syndromes may be associated with malignancy in a variety of ways. Cause and effect are difficult to define clearly in many situations, however. Certain chronic rheumatic diseases have been associated with increased risk of the subsequent development of malignancy; one example is lymphoma in an individual with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. The converse situation also exists, in that certain rheumatic diseases, such as dermatomyositis, are seen more frequently in the presence of an underlying malignancy. Little is understood regarding the pathogenesis of connective tissue disease in association with neoplastic disease. Other factors can contribute to the association of musculoskeletal syndromes and malignancy. Many of the medications used to treat rheumatic diseases modulate the immune system and may be associated directly or indirectly with increased risk for the subsequent development of malignancy. In unusual circumstances, musculoskeletal involvement occurs as a paraneoplastic process, defined as a hormonal, neurologic, hematologic, or biochemical disturbance associated with malignancy, but not directly related to invasion by the neoplasm or its metastases.1

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

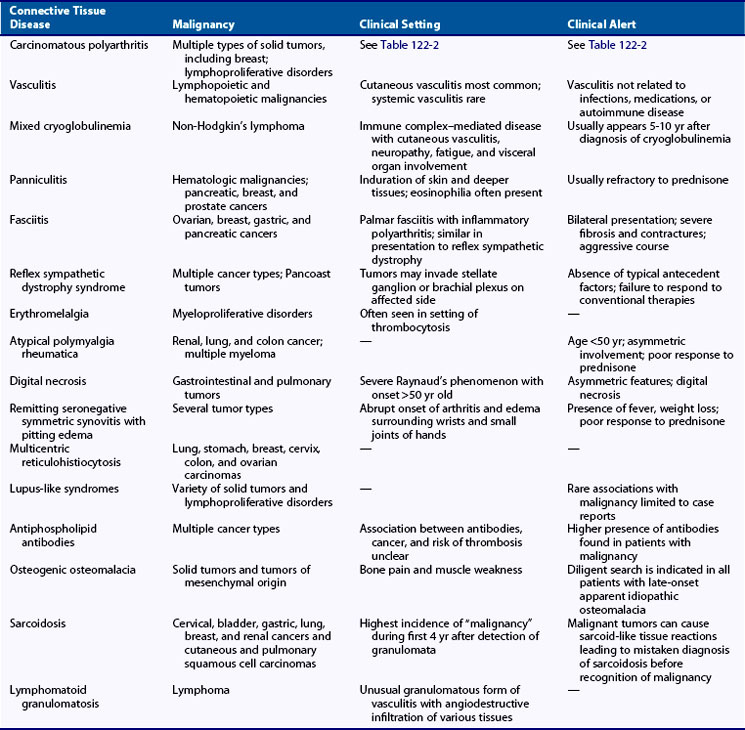

Musculoskeletal syndromes can develop as a manifestation of a paraneoplastic process and occasionally can be the first presentation of an underlying malignancy. Hematologic malignancies, lymphoproliferative disorders, and solid tumors are associated with a wide variety of paraneoplastic rheumatic syndromes. Older age of onset, atypical features of rheumatic disease, and absence of response to glucocorticoids or other conventional therapy may suggest a paraneoplastic process. Knowledge of the associations with rheumatic syndromes and underlying malignancy is crucial when caring for these patients. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, amyloidosis, and secondary gout are reviewed in Chapters 102, 116, 94, and 95. Table 122-1 lists common paraneoplastic associations.

Carcinomatous Polyarthritis

The term carcinomatous polyarthritis is used to describe the development of arthritis in association with malignancy, but it is distinct from arthritis associated with metastasis or direct tumor invasion. Table 122-2 lists common features of carcinomatous polyarthritis. It generally occurs in patients who are older; it has an explosive onset and often develops in close temporal correlation with discovery of the malignancy. Although it can have various presentations and may mimic the appearance of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)2 or asymptomatic migratory polyarthritis,3 carcinomatous polyarthritis is more often a seronegative asymmetric disease with predominant involvement of the lower extremities and some sparing of the small joints of the hands. No evidence of direct tumor extension or metastasis has been found, and no specific histologic or radiographic appearance has been identified. Carcinomatous polyarthritis can occur in association with many types of malignancy, but has been reported in greatest frequency in association with breast, colon, lung, and ovarian cancers and with lymphoproliferative disorders.4 The underlying pathogenesis of this process has not been elucidated; however, the arthritic symptoms may be improved with successful treatment of the malignancy.5

Table 122-2 Features of Carcinomatous Polyarthritis

Vasculitis

Vasculitis in association with malignancy is uncommon and has a reported prevalence of only 8% among patients with malignancy.6 The association seems to be significantly higher with lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative disorders than with solid tumors, and vasculitis commonly predates the identification of malignancy. The vasculitic process is most often small vessel and cutaneous and only rarely involves significant organs. Up to 5% of patients with cutaneous vasculitis have an underlying neoplasm.7 Treatment often requires the use of glucocorticoids and therapy directed against the underlying malignancy, although it seems that this is often ineffective. Table 122-1 shows malignancies associated with vasculitis. In the setting of malignancy, it is believed that persistent antigen stimulation from the tumor results in T cell activation or immune complex formation and deposition.

The development of small vessel vasculitis has been reported to antedate and postdate the development of lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases. One group looked retrospectively at 222 patients with vasculitis and identified 11 who had developed an associated malignancy.8 Of these 11 patients, 7 had hematologic neoplasia, and 4 had malignant solid tumors. Nine of the patients manifested cutaneous vasculitis, and the remaining 2 had vasculitic involvement in the bowel. In 4 patients, the development of vasculitis antedated the diagnosis of malignancy.8 Similar findings were reported by investigators, who found an underlying malignancy in 8 of 192 patients with cutaneous vasculitis. Most malignancies were hematologic (6 of 8) and predated (5 of 8) the diagnosis of cancer.9 In a retrospective analysis of 23 patients with cutaneous vasculitis and hematologic malignancies, the authors were able to attribute the presence of vasculitis to the malignancy itself in 61% of cases.10

Systemic vasculitis is much less commonly associated with underlying malignancy. Case reports and small series have found antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–negative and ANCA-positive vasculitis associated with hematologic malignancies.11–13 Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis) has likewise been associated with the development of several types of malignancies, including lymphoproliferative disorders, bladder cancer, and renal cell carcinoma.14,15 In some cases, the malignancy was diagnosed within months of the diagnosis of GPA,14 and in other reports, cancer developed many years after diagnosis and treatment of vasculitis,15 making it unclear whether the malignancies were a result of the vasculitis or possibly the treatment. A group from the Cleveland Clinic did a retrospective study to assess directly the temporal relationship between vasculitis and cancer.16 During an 18-year study period, the authors found only 12 cases of vasculitis and cancer diagnosed within the same 12-month period: Six patients had lymphoproliferative disorders, and 6 had solid tumors. In most cases, the vasculitis responded partially to immunosuppressive therapy, but investigators observed a more impressive improvement in vasculitis with definitive treatment for the underlying malignancy. A more recent study found 20 cases of malignancy among 200 patients with ANCA-positive vasculitis; 6 were diagnosed concurrently with a diagnosis of vasculitis, and 14 predated vasculitis by a median of 96 months.17 Only 4 of 20 malignancies in this series were lymphoproliferative; the remaining malignancies were solid organ tumors.

Vasculitis associated with underlying malignancy is often poorly responsive to conventional therapy directed against the vasculitis. In one series of 13 patients with cutaneous vasculitis and lymphoproliferative or myeloproliferative disorder, symptoms of vasculitis were poorly responsive to therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and antiserotonin agents. Although investigators described lessening of the severity of vasculitis after chemotherapy directed against the malignancy, they generally found chemotherapy to be ineffective. Of 13 patients identified, 10 died as a direct result of the malignancy.18 Similarly, Hutson and Hoffman16 found general concurrence between improvement in vasculitic syndrome and definitive treatment for the associated underlying malignancy. More recently, a study of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis associated with solid tumors (most commonly lung, breast, and prostate) found a significant response to immunosuppressive therapy directed against the vasculitis, although concurrent treatments for the underlying malignancy were undertaken.19

Cryoglobulinema

Type I: Monoclonal immunoglobulin, either IgG or IgM; this type is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders.

Type II: Monoclonal IgM directed against polyclonal IgG; type II cryoglobulins were initially thought to be idiopathic and were known as mixed essential cryoglobulinemia. With the identification of hepatitis C virus (HCV), it has been discovered that most of these patients have HCV infection that is directly involved in the pathogenesis of the cryoglobulins. Specific epitopes of HCV antigens are recognized by IgG components of immune complexes, and viral particles are found in the cryoprecipitate.20 One study found clonal B cell populations in the peripheral blood of 48% of HCV-positive patients with type II cryoglobulinemia, many of whom were eventually diagnosed with a B cell malignancy.21 Overall, it is estimated that approximately 5% to 8% of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia may go on to develop non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, usually after 5 to 10 years of cryoglobulinemia.22,23 The risk of developing non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma among HCV-positive cryoglobulinemic patients may be 35 times higher than in the general population.24 Other data suggest that HCV infection may be associated with other hematologic malignancies.25,26 At this time, the subset of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia who will develop lymphoma cannot be predicted.

Type III: Mixed polyclonal IgG and IgM; type III cryoglobulins are commonly seen with a variety of illnesses, including connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE] and RA) and infections. In one study of 607 patients diagnosed with mixed cryoglobulinemia, 27 cases of hematologic malignancy were identified. Of these, systemic autoimmune diseases were detected in 56% of cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.26

Panniculitis

The fasciitis-panniculitis syndrome, which includes eosinophilic fasciitis, is characterized by swelling and induration of the skin that extends into deeper subcutaneous tissues and is associated with fibrosis and chronic inflammation. Patients may develop arthritis and subcutaneous nodules similar to those seen in erythema nodosum. The arthropathy seems to be secondary to periarticular fat necrosis, can be monoarticular or polyarticular,27 and may mimic RA or juvenile RA.28 Blood and tissue eosinophilia is commonly, but not always, present.29 This syndrome can be idiopathic and have a benign course, or it can be secondary to a variety of infectious, vascular, or traumatic events. In a few patients, the fasciitis-panniculitis syndrome is associated with an underlying malignancy. Hematologic malignancies are most often associated with this syndrome and are usually diagnosed concurrently or within the first year.30,31 Pancreatic cancer and pancreatitis also can be associated with this syndrome.27,28 Patients with cancer-associated fasciitis-panniculitis syndrome are predominantly female and are generally refractory to prednisone.29

Palmar Fasciitis

Palmar fasciitis with arthritis is a syndrome characterized by progressive bilateral contractures of the digits, fibrosis of the palmar fascia, and inflammatory polyarthritis.32,33 The metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints are most commonly affected; other affected joints include the elbows, wrists, knees, ankles, and feet. Indurated reticulate palmar erythema can also be seen as part of the palmar fasciitis spectrum.34 Palmar fasciitis is almost uniformly associated with the presence of an underlying malignancy, most often ovarian, breast, gastric, and pancreatic tumors.33,35,36 Although initially thought to be an atypical variant of reflex sympathetic dystrophy, the severity of manifestations, bilateral presentation, and strong association with occult malignancy suggest that, in these cases, palmar fasciitis is a distinct entity that behaves as a paraneoplastic syndrome. Glucocorticoids, chemotherapy, or both do not seem to result in improvement, although fasciitis occasionally regresses with treatment of the underlying malignancy.32

Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy and a variant, shoulder-hand syndrome, are characterized by regional pain, swelling, vasomotor instability, and focal osteoporosis in a given limb; this condition is thought to be caused by sympathetic dysfunction. Absence of associated antecedent factors, such as stroke, myocardial infarction, or trauma, and failure to respond to conventional therapy warrant a search for an underlying malignancy. A variety of malignancies have been associated with the development of reflex sympathetic dystrophy or its variants.37,38 Pancoast tumor of the lung apices and other malignancies that infiltrate the stellate ganglion or brachial plexus have been described in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy.39–41 Therapy directed against the underlying malignancy may lead to some amelioration of symptoms associated with reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

Erythromelalgia

Erythromelalgia is an enigmatic condition characterized by attacks of severe burning, erythema, and warmth of the extremities with symptoms predominantly involving the feet.42,43 Symptoms are often exacerbated when the extremities are placed in a dependent position, during ambulation, or during exposure to increased temperatures. Partial relief can be obtained through elevation or cooling of the extremity. This disorder can occur idiopathically (60%) or secondary to another disease (40%).42,44 Myeloproliferative disorders, including polycythemia vera and essential thrombocytosis, are common primary causes and have been found to precede the diagnosis of erythromelalgia by several years.7,43,45 The underlying pathophysiology of this disease is unknown; however, it is often associated with thrombocythemia. In the largest published retrospective cohort, 168 patients at the Mayo Clinic were identified with this diagnosis between 1970 and 1994.46 The authors found that after a mean follow-up of 8.7 years, 31.9% of patients reported worsening of disease, 26.6% reported no change, 30.9% reported improvement, and 10.6% reported complete resolution of symptoms. Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed a significant decrease in survival compared with controls. A history of myeloproliferative disease was found in 15 of 168 patients. The exact cause of the symptoms is unclear, but microvascular arteriovenous shunting has been hypothesized.47 In cases of secondary erythromelalgia, platelet breakdown products and platelet microthrombi may underlie disease pathogenesis.7 The most effective therapy seems to be the use of daily aspirin, leading to significant relief of symptoms, which is believed to be related to inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1. A host of other therapies have been tried with varying success.48 Because of the association with myeloproliferative diseases, routine monitoring with complete blood counts is prudent.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Polymyalgia rheumatica is a disorder affecting older adults that manifests with discomfort and stiffness in the shoulder and hip girdle, fatigue, anemia of chronic disease, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Classically, this condition responds to moderate doses of prednisone within 48 hours. A variety of other conditions can have presentations that mimic polymyalgia rheumatica, including other rheumatic disorders, systemic infections, and malignancy.49 Although the association between polymyalgia rheumatica and malignancy has been controversial, atypical features of polymyalgia rheumatica may suggest the presence of occult malignancy, including age younger than 50 years, limited or asymmetric involvement of typical sites, ESR less than 40 mm/hr or greater than 100 mm/hr, severe anemia, proteinuria, and poor or delayed response to 20 mg daily of prednisone. Kidney, lung, and colon cancer and multiple myeloma are most often found in patients presenting with atypical polymyalgia rheumatica.50–52 One study of patients undergoing evaluation for possible polymyalgia rheumatica found 10% to have a diagnosis of malignant neoplasms.53 In contrast, several prospective studies have shown that patients who present with classic polymyalgia rheumatica or temporal arteritis do not seem to have an increased risk of developing malignancy over age-matched controls.54–58

Raynaud’s Phenomenon and Digital Necrosis

The development of digital necrosis or profound Raynaud’s phenomenon may suggest the presence of infection, inflammatory disease, or an underlying malignancy. In patients older than 50 years, the development of Raynaud’s phenomenon, particularly in an asymmetric fashion or in association with digital necrosis, should raise the possibility that this is a paraneoplastic process. These features often antedate the diagnosis of the malignancy by an average of 7 to 9 months.59,60 A variety of solid tumors and lymphoproliferative disorders have been associated with this syndrome.59–65 Certainly, the presence of digital necrosis in patients with dermatomyositis is highly suggestive of the presence of an underlying malignancy. Mechanisms proposed include cryoglobulinemia, immune complex–induced vasospasm, hypercoagulability, marantic endocarditis with emboli, and necrotizing vasculitis.65 Therapy with interferon-α also has been reported in association with the development of Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital necrosis.66–68

Remitting Seronegative Symmetric Synovitis with Pitting Edema

Remitting seronegative symmetric synovitis with pitting edema (RS3PE) is an uncommon disorder primarily affecting the metacarpophalangeal joints and the wrists. Although the underlying cause and pathogenesis of this illness are unclear, lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndromes, and several solid tumors, mostly adenocarcinoma, all have been reported in association with it.69–73 One retrospective study from a single center in the United States found that 3 of 14 patients with RS3PE developed cancer.74 Characteristics that suggest possible underlying malignancy include the presence of systemic features, such as fever or weight loss, and a poor response to glucocorticoids.71,72

Multicentric Reticulohistiocytosis

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is a rare condition characterized by the presence of cutaneous papules often associated with a destructive arthritis of the interphalangeal joints of the hands. The papules are flesh-colored to brown-yellow and are classically present in the periungual region and on the dorsal hands and face. Arthritis mutilans may develop in 50% of cases. The characteristic histologic appearance of tissue infiltration with histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells can be found in affected skin, joints, and occasionally internal organs.75 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis has been reported in association with hyperlipidemia, malignancies, and autoimmune diseases. Malignancy has been associated in 25% to 31% of cases, although most literature consists of individual case reports.76,77 The most frequently seen malignancies include carcinoma of the lung, stomach, breast, cervix, colon, and ovary.75

Lupus-like Syndromes

Lupus-like syndromes are rarely associated with underlying malignancy. Isolated case reports have described lupus-like syndromes with ovarian carcinoma78,79 and hairy cell leukemia80; subacute cutaneous lupus was reported in a patient with breast carcinoma.81 Studies on the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) in patients with cancer have yielded mixed results. Two studies were unable to find a significantly increased prevalence of ANAs in patients with solid tumor or lymphoma compared with healthy controls.82,83 In contrast, one smaller study found an increased prevalence in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma compared with controls (21% vs. 0),84 and another study found a prevalence of ANAs of 27.7% in 274 patients with various malignancies compared with 6.45% of 140 healthy controls.85 No predictive features seem to suggest occult malignancy in patients presenting with lupus-like syndromes or positive ANAs.

Antiphospholipid Antibodies

Several studies have shown the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with solid tumors and lymphoproliferative disorders at a higher frequency than the 1% to 5% seen in the general population.86,87 An early study of 216 consecutive patients with cancer found 22% positive for anticardiolipin antibodies compared with 3.4% in controls. This study found a two-fold increase in the development of thromboembolism in patients with positive antibodies compared with patients with negative serologies; it also indicated that most thromboembolic events occurred in patients with higher antibody titers.88 Other studies have confirmed the association between malignancy and antiphospholipid antibodies (12.5% to 68%), but have been unable to show a correlation with thromboembolic events.84,86,89–93 A correlation between antibody titer and disease activity has been shown in some studies,81,83 and decreased survival in others.93,94 A review of the literature concluded that antiphospholipid antibodies resolve in one-third of cancer patients after treatment for the underlying malignancy.95

Studies of the prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in unselected patient populations have shown an association with underlying malignancy. A prospective study in France found that 7% of 1014 consecutive patients admitted to a medical ward had antiphospholipid antibodies.96 In antibody-positive patients, cancer was the most frequently associated disease. A more recent study in patients presenting with a first ischemic stroke found a significantly higher rate of development of cancer within 12 months in patients who had anticardiolipin antibodies (19% vs. 5%).97

Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia is the softening of bones often associated with failure of adequate calcification secondary to renal dysfunction or to lack of vitamin D. Osteomalacia has been associated with benign and malignant solid tissue and mesenchymal tumors.98 Tumors causing oncogenic osteomalacia have been shown to overproduce fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), and elevated serum levels of FGF-23 can be detected in patients with this paraneoplastic condition.99,100 Octreotide scintigraphy may be a useful tool for identifying occult tumors.101 With removal of the tumor, there often seems to be resolution of the osteomalacia and normalization of serum FGF-23 levels.100

Sarcoidosis

Noncaseating granulomata can occur in numerous settings and are not pathognomonic for sarcoidosis. Granulomata resembling those of sarcoidosis may be found in lymph nodes that drain sites of malignancy. These tumor-related tissue reactions resulting in granuloma formation have been described with many types of malignant lesions, including solid tumors and lymphomas.102,103 The clinical and radiographic presentation of sarcoidosis and cancer can be virtually indistinguishable, making it important to pursue aggressive evaluation in a patient with sarcoidosis.104,105

The risk of malignancy developing in patients with an established diagnosis of sarcoidosis is controversial. Some studies have shown an increased risk of developing lung cancer and lymphoma,106–108 whereas others have shown no increased risk of cancer over the general population.104,109,110

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a rare disorder with angiodestructive and lymphoproliferative features involving the lung and, less often, the skin and central nervous system. Although lymphocytic infiltration of vessels is a hallmark of the disease, lymphomatoid granulomatosis now seems to fall within the spectrum of lymphoproliferative disorders.111 Despite the predominance of T cells within inflammatory infiltrates, studies have suggested that an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated B cell proliferation may underlie the pathogenesis of the disease.112,113 Prognosis is generally poor, with a median survival from diagnosis of 14 months,114 although more recent reports suggest some response to rituximab therapy.115,116 Frank lymphomas evolve in 25% of cases.117

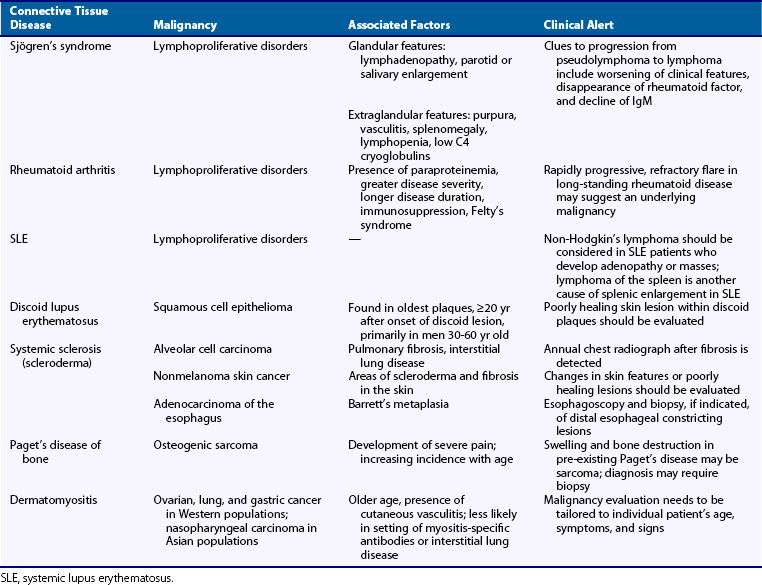

Inflammatory Myopathies

The inflammatory myopathies in adult populations encompass a group of illnesses characterized by an idiopathic immune-mediated attack on skeletal muscle resulting in muscle weakness. Many associations between the inflammatory myopathies and the presence of malignancy have been noted, but the reason for the association remains unknown.118 Dermatomyositis has classically been associated with occult malignancies, whereas associations between polymyositis and inclusion body myositis are becoming increasingly recognized. A further issue is whether the inflammatory myopathy predates the malignancy and can be considered a primary rheumatic disease with known risks of developing malignancy, or whether it simply represents a manifestation of a paraneoplastic process.

On average, the prevalence of malignancy in association with inflammatory myopathies has been approximately 15% to 25%, which appears to be consistent across populations studied. The frequency of malignancy has ranged, however, from 6% to 60% in patients with dermatomyositis, and from 0 to 28% in patients with polymyositis.118,119 Other estimates have placed the incidence of cancer in patients with inflammatory myopathies at five to seven times that of the general population.118

Dermatomyositis has been associated with a wide range of malignancies; solid tumors are most often seen in cancer-associated myositis as opposed to lymphoid malignancies. Ovarian, lung, and gastric tumors are most common in European populations, and nasopharyngeal malignancies in Asian populations. Studies have confirmed a strong association between dermatomyositis and malignancy. Hill and colleagues120 studied a pooled cohort of patients from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland and found 198 cases of cancer in 618 patients with dermatomyositis. The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for malignancy with dermatomyositis was 3. Similar results were found in a Scottish cohort of 286 patients with dermatomyositis.121 Of these patients, 77 were found to have underlying malignancies, with an SIR of 3.3 to 7.7. Buchbinder and co-workers122 used strict histopathologic criteria to classify myositis in patients from Victoria, Australia. This group found 36 cases of cancer in 85 patients diagnosed with dermatomyositis and an SIR of 4.3 to 6.2. All of these studies have suggested that cancers are most commonly diagnosed within 1 to 2 years of diagnosis of dermatomyositis.

In contrast to previous work, studies of Asian populations have shown a higher association of nasopharyngeal carcinomas with dermatomyositis. In a nationwide Taiwanese study, 9.4% of 1012 patients with dermatomyositis were found to have an underlying malignancy, the most common of which was nasopharyngeal cancer, followed by lung cancer.123,124 In a smaller study, 66.6% of 15 dermatomyositis patients in Singapore had malignancies, most of which were nasopharyngeal carcinoma.125 Eight white patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma within 1 year of diagnosis of dermatomyositis were reported more recently in Tunisia.126 A similar study from Japan found that cancer was diagnosed in 24% of dermatomyositis patients; most cases involved gastric cancer, a common malignancy in the Japanese population.127

In polymyositis, the relative risk for developing internal malignancies seems to be lower than that for dermatomyositis, but it is consistently increased over that expected in the general population. Studies have found a 14% to 30% prevalence of cancer among patients with polymyositis, with SIRs increased to 1.2 to 2.1.120–123 The nationwide Taiwanese study found a 4.4% incidence of cancer among 643 patients with polymyositis, with an SIR of 2.15 compared with the general population.124 Small numbers of many types of cancers were found. These studies confirm results reported in previous large studies of Swedish and Finnish populations and a 1994 meta-analysis of all published case-control and cohort studies of malignancy and myositis, which identified an odds ratio for the association of cancer with dermatomyositis of 4.4, and of cancer with polymyositis of 2.1.128

In amyopathic dermatomyositis, a variant of dermatomyositis in which typical cutaneous manifestations are present with subclinical or no identifiable muscle disease, the association with underlying malignancy is now becoming clear. Whereas previous published reports were limited to small groups of patients,125,129–131 recently published cohort studies and a systematic review of the amyopathic dermatomyositis literature have suggested similar associations between amyopathic dermatomyositis and internal malignancies.127,132,133

Far less is known about the association of inclusion body myositis with underlying malignancy. In Buchbinder’s study from Northern Europe, 52 patients were identified with inclusion body myositis.122 Of these patients, 12 were found to have internal malignancies, with an SIR of 2.4. The numbers of each type of cancer seen are too small to reveal specific associations.107

Not all studies concur regarding the association between the inflammatory myopathies and malignancy.134,135 In a study done at the Mayo Clinic, patients with myositis did not seem to be at statistically significant risk for the development of malignancy. No clinical differences were seen between patients who developed a malignancy and patients who did not.135

Despite the negative results of some studies, it seems that most work supports the notion of an increased risk of malignancy in association with dermatomyositis and polymyositis. For patients in whom an inflammatory myopathy has been diagnosed, a workup for the presence of malignancy should be done. The extent of this workup has been debated, however, because extensive undirected searches often result in a very low yield. It is probably rare for an undirected workup to yield evidence of malignancy in polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients136; any workup should be tailored to the individual patient’s age, symptoms, and signs. Studies have suggested that imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis may increase the potential for discovery of underlying malignancy.137,138 Other studies have suggested the use of serum tumor markers (CA125 and CA19-9) to augment detection of patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis at highest risk for associated malignancy.139 More recently, a prospective study of whole body positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) was found to be comparable with broad conventional screening (including chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT scans, among other tests).140 Malignancies associated with inflammatory myopathies have been known to develop many years after the diagnosis of muscle disease, so continued vigilance and repeated screening for malignancy are warranted.

In certain cohorts, the risk of malignancy may be higher, including those with older age at diagnosis,141 evidence of distal extremity weakness,142 and prominent pharyngeal and diaphragmatic involvement.142 Patients with myositis-associated autoantibodies may be at less risk for the development of malignancy.142–144 More recent work has suggested that the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis145 and cutaneous ulceration,142 as well as the absence of pulmonary involvement,141 increases further the possibility that an underlying malignancy is present.

Although the pathogenesis is unknown, the types of malignancy associated with inflammatory myopathies have been varied, including adenocarcinomas of the breast, ovaries, and stomach. Most cases of dermatomyositis and malignancy seem to occur within 1 year of each other, with myositis diagnosed first in most cases.118 When identified, removal of the malignancy may result in improvement of the myopathic process, which further supports the paraneoplastic nature of myositis in some cases.146

Risks of Developing Lymphoproliferative Disorders in Rheumatic Diseases

Since the 1960s, increasing numbers of reports have described the association between rheumatic disease and the development of malignancy, particularly lymphoproliferative disorder. Table 122-3 shows pre-existing connective tissue diseases that have been associated with malignancy. Much of what is known about associations between rheumatic disease and malignancy is drawn from retrospective and prospective cohort studies, registry linkage studies, small series, and case reports. This is thought to be mediated, at least in part, by chronic immune stimulation and hyperactivity that may lead to malignant transformation. In addition, certain confounding factors need to be considered when the risk of development of malignancy is assessed, including the potential oncogenic properties of many of the immunosuppressive and cytotoxic medications prescribed to treat autoimmune diseases. Lymphoproliferative disorders have developed in patients with rheumatic diseases and in recipients of solid organ transplantations treated with immunosuppressive agents. EBV has been implicated in the development of lymphoid neoplasia in immunosuppressed patients. In the following sections, many of the rheumatic diseases and the therapies used to treat them are discussed.

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune exocrinopathy, is characterized by a benign lymphocytic infiltrate of salivary and lacrimal glands that leads to the development of sicca syndrome (keratoconjunctivitis and xerostomia).147 The development of lymphoproliferative disorders in the setting of Sjögren’s syndrome is perhaps the prototypic example of chronic autoimmune disease with increased risk of malignancy. In 1964, investigators first reported the development of four cases of lymphoproliferative disorders in a cohort of 58 patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.148 In 1978, 7 of 136 patients with sicca syndrome were identified as having developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Compared with the expected incidence of cancer among women of the same age range, a 44-fold increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was noted.149 These findings have been reproduced numerous times in other cohorts. Lymphoproliferative disorders complicate approximately 4% to 10% of cases of primary Sjögren’s syndrome.150–157 The relative risk for development of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome ranges from 6 to 44,149,158–163 and a meta-analysis of cohort studies has found a pooled SIR of 18.8.160 Most lymphoproliferative disorders were non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, specifically mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, other marginal-zone lymphomas, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma.155,156 Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and multiple myeloma were more rarely reported.149,153,154,159

Generally, the development of lymphoma is a late manifestation of Sjögren’s syndrome, often seen after 6.5 years of disease.151,152,164 Clinical and laboratory features seem to be associated with or predictive of development of lymphoproliferative disorders, including palpable purpura,148,153,154,163 cutaneous ulcerations,150 cryoglobulinemia,154,155 low serum complement levels,,153–155165 monoclonal gammopathies,166,167 cytopenias,148,155,163 splenomegaly,148,155 and adenopathy.150 Progression to high-grade lymphoma portends a poor prognosis.* In contrast, the incidence of other malignancies or all-cause mortality was not increased in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome compared with the general population.159,163,164,168 It is believed that chronic B cell stimulation may lead to the malignant transformation of clonal lines characteristic of Sjögren’s syndrome.147 The presence of a viral trigger accounting for malignant transformation is one possible theory. EBV, among other viruses, has been implicated, but studies have failed to find EBV or other viral particles in lymphoma specimens associated with Sjögren’s syndrome.169

Other reports have described the presence of chromosomal translocations with increased frequency in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome who have developed lymphoma. One group of investigators identified the presence of translocations of the proto-oncogene bcl-2170 in 5 of 7 patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and lymphoma by the use of polymerase chain reaction. Such translocations were found in peripheral blood or bone marrow in 5% of unselected patients with Sjögren’s syndrome without evidence of lymphoma in another study.171 Conversely, no evidence of bcl-2 translocations was present in 50 salivary gland biopsy specimens of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome without evidence of lymphoma.172 Analysis of biopsy specimens taken before the development of lymphoma from the 7 patients previously mentioned revealed no evidence of bcl-2 translocation. Translocation seemed to correlate with the development of lymphoma in at least a subset of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, and the use of polymerase chain reaction technology may allow early detection of malignant transformation.171–173

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Data from numerous studies since the 1970s are persuasive that RA is associated with a twofold to threefold increased risk for the development of lymphoproliferative disorders, the magnitude of which has remained constant despite dramatic changes in therapy. Many factors, including chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation, in addition to potential oncogenic properties of immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of RA, must be considered when the risk of development of hematologic malignancies is evaluated. It is often difficult to separate the effects of medication use from the underlying severity of inflammation that makes medication use necessary or indicated, a concept termed confounding by indication.174 This association has been highlighted further by widespread use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for patients with refractory disease and the potential for these medications to interfere with innate immune tumor surveillance.

In 1978, an SIR of 2.7 for lymphoma was reported in a group of 46,101 Finnish RA patients compared with the general population.175 A similarly increased risk of 2.4 for lymphoma was seen later in a group of 20,699 Danish patients,176 and an SIR of 1.9 to 2 was reported in a large cohort of 76,527 Swedish patients.177,178 In the United States, an increased risk of 1.9 was found in a cohort of 18,527 patients,179 and an SIR of 2.2 was noted in a separate cohort of 8458 patients 65 years old and older.180 In the United Kingdom, an SIR of 2 to 2.4 for lymphoma was observed in an inception cohort of 2015 patients with inflammatory arthritis compared with the general population,181 and an SIR of 2.04 to 2.39 was seen for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a cohort of 26,623 RA patients in Scotland.182 A meta-analysis of nine cohort studies of RA patients found a pooled SIR of 3.9 for lymphoma using a random effects model.161 Canadian investigators found an increased risk of leukemia (SIR, 2.47) among RA patients, but were unable to confirm elevated rates of lymphomas compared with the general population.183 Data from case-control studies of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma have shown similar results: Odds ratios of 1.3 to 1.5 were found for underlying RA.160,162 These associations have been recently confirmed in other populations, including patients from Japan,184 Taiwan,185 California,186 and Spain.187 In general, lymphomas in patients with RA seem to be predominately diffuse large B cell type and recently have been shown to favor nongerminal center subtypes.188

Most studies have suggested that the risk for development of lymphoma is related to the degree of inflammation. The Swedish group identified high inflammatory activity (defined by ESR, swollen and tender joint counts, and the physician’s global assessment of disease activity) as a significant risk factor, with an odds ratio of 25.8 compared with low disease activity.189 No association between any specific drug and the development of lymphoma was identified; however, the cohort examined was treated between 1965 and 1983, and few of these patients were apparently treated with immunosuppressive drugs, making the lack of association less certain. In a follow-up case-control study of 378 lymphomas in a Swedish group of RA patients published more recently, a 71-fold increased risk of lymphoma was reported in patients with high cumulative disease activity compared with low disease activity.190 Immunosuppressive therapy did not seem to modify risk for lymphoma in this study. Patients did not have increased rates of lymphoma development before disease onset.191 Patients with Felty’s syndrome (a variant of RA associated with neutropenia and splenomegaly) were found in a Veterans Affairs study of 906 men to have a twofold increase in total cancer incidence, but a 12-fold increase in risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.192

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drug Therapy

Several studies have looked at the contribution of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy to the elevated risk of malignancy in RA patients. A prospective, observational study was performed in a group of Canadian RA patients enrolled in a DMARD registry.193 Although this study found an increased rate of lymphoproliferative disorders in this cohort compared with the general Canadian population (SIR, 8.05), no significant differences in DMARD exposure were noted between patients who developed malignancy and patients who did not. A second group of Canadian investigators similarly identified an increased risk for the development of lymphoma and myeloma in RA patients overall compared with control groups.194 In this study, the risk of lymphoma and myeloma seemed to be fourfold greater in the RA group when DMARD use was not controlled for and 3.4-fold greater when individual DMARD use was controlled for. Despite the low level of DMARD exposure in this population, no strong effect of DMARD use was seen.

Similar effects of DMARD use were seen in the study of Swedish patients with RA and lymphoma: Treatment with any DMARD (odds ratio [OR], 0.9) or specific use of methotrexate (OR, 0.8) did not seem to be associated with increased risk of lymphoma compared with DMARD-naïve RA patients; however, no patients had been treated with TNF inhibition.177 In contrast, a European cohort of RA patients enrolled in a DMARD registry was evaluated longitudinally for the development of malignancies.195 Investigators found an increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with the highest cumulative exposure to DMARDs compared with patients with less than 1 year of exposure (SIR, 4.82).

Although inconclusive, data from these studies when taken together suggest a possible increased risk for the development of lymphoproliferative disorders in RA patients treated with DMARDs. More recent studies have suggested, however, that this increased risk may be due to the duration and severity of the underlying disorder, rather than to specific medication use. Associations of specific immunosuppressive therapy for the treatment of autoimmune diseases are discussed further in Chapters 61 and 62.

Risk of Solid Tumor in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Despite persuasive evidence of increased risks of lymphoproliferative disorders associated with underlying RA, overall rates of all-site malignancies do not seem to be higher compared with the general population.175–177,182,183,196,197 The overall “null” result of all malignancies is due to the combination of increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders offset by an apparently decreased risk of colorectal malignancies.175–177,182,183,198 The decreased risk of colorectal cancer has been attributed to long-term use of NSAIDs among RA patients. Aside from lymphoproliferative disorders, only a few solid tumors, including lung cancer and skin cancer, have been associated with RA.

Increased risk of lung cancer in RA patients has been seen in multiple studies.175–177,182–187,196–198 A study evaluating three separate RA cohorts (an inpatient registry of 53,067 prevalent cases of RA, an inception cohort of 3703 incident RA cases, and a registry of 4160 RA patients treated with TNF inhibitors) found a consistently increased risk of lung cancer in all cohorts (SIR, 1.48 to 2.4) compared with the general population.81,198 This association may be related to tobacco use, which seems to be a common risk factor for the development of RA, in addition to its well-known association with lung cancer,199 although the particular association of lung cancer among RA patients who smoke is unknown. Similarly, a study of lung cancer in a cohort of 8768 U.S. veterans (92% male) with RA found an increased risk of lung cancer (OR, 1.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23 to 1.65) after adjustment for covariates such as age, gender, and tobacco exposure.200

A slightly increased risk for the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer (most commonly basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma) has been noted in several studies,175,176,198,201,202 although the significance of these tumors, which carry a low probability of metastasis, is unclear. Unfortunately, nonmelanoma skin cancer is rarely captured in national cancer registries, so its incidence among the general population or subpopulations such as RA is difficult to quantify or compare. Furthermore, important risk factors for nonmelanoma skin cancer, including ultraviolet light exposure, are almost impossible to quantitate in observational studies. What is of greater concern, however, are newer data suggesting an increased rate of melanoma among patients with RA.180,185,202–204 Because of the suggestion of increased risk of skin cancer, whether attributed to underlying disease or immunosuppressive therapies, it is reasonable to suggest periodic skin examinations in RA patients, particularly those with other risk factors, including smoking and increased ultraviolet light exposure. Certainly, all suspicious lesions should be evaluated by a dermatologist and biopsy strongly considered.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The risks of developing malignancy in association with SLE have been difficult to estimate in the past. Small series and cohort studies have noted that patients with SLE might be at increased risk for malignancy, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, sarcoma, and breast carcinoma.205–209 Other small series have not found differences,210 however, or have found infrequent associations211 in number or type of malignancy between patients with lupus and the general population.210 Conflicting results also are seen in case-control studies of larger groups of patients, with some cohorts showing an increased overall risk of malignancy,212–214 although others have failed to do so.215–218 Some studies that did not find increased risk of overall malignancies in patients with SLE have shown increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders, however.160,162,216–218 Confounding factors complicating interpretation of these studies include possible incomplete ascertainment of malignancies, inclusion of nonrepresentative cohorts of patients with SLE, and selection of inappropriate control populations.219

To determine more adequately whether individuals with SLE are at increased risk, studies of large multinational cohorts, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses of pooled data are necessary. The SIR of individual studies has ranged from 1.1 to 2.6.220 A meta-analysis of six of the clinical cohort studies found a slightly increased risk of overall malignancies in cohorts of patients with SLE, with an SIR of 1.58.221 This analysis showed an increased risk of lymphoma in these cohorts, with an SIR of 3.57 for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and 2.35 for Hodgkin’s disease. A separately performed meta-analysis of the incidence of lymphoma in patients with SLE found an SIR of 7.4.161 Individual hospital discharge database studies have shown a consistently higher risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (SIR, 3.72 to 6.7), but these studies examined only hospitalized patients with SLE.200 Pooled analysis showed a slightly elevated risk for the development of breast cancer, with an SIR of 1.53, but they did not find an increased risk of lung or colorectal cancer in these patients.221 The same confounding factors influencing individual studies are a factor in interpreting these pooled data.

A more recent series of studies analyzing nearly 9500 lupus patients (≈77,000 patient-years of observation) in a multinational cohort study has helped to define better potential associations with malignancy.222,223 The authors found a slightly increased risk of malignancies overall (SIR, 1.15) with higher risks for the development of hematologic malignancies (SIR, 2.75), particularly non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (SIR, 3.64).222 Forty-two cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma were identified, most of which were of aggressive histologic subtypes.224 The incidence of lymphoma in this study was evident early in the course of SLE, rather than after many years of chronic disease activity or use of multiple immnosuppressive medications.223,225 The elevated risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in this cohort seemed to be independent of race or ethnicity, although white patients seemed to have higher rates of malignancy in general compared with patients of other ethnicities.226 In a case-control study within the multisite international SLE cohort, age, disease-related damage, and smoking were found to be associated with increased risk of malignancy; use of immunosuppressant medications (particularly lagged 5 years) may contribute to increased risk of hematologic malignancy.227

Although the exact cause of the association is unknown, several theories have arisen to explain the possible connection between SLE and malignancy, especially B cell lymphoma. Some authors have postulated that certain immunologic defects may predispose patients to SLE and B cell lymphoma, including apoptosis dysfunction, chronic antigenic stimulation, and overexpression of bcl-2 oncogene.220,228 Viruses, EBV in particular, also have been postulated as part of the development of SLE and lymphoma.220,228 Studies have not conclusively validated any of these theories to date, however.

The relative prevalence of cervical cancer in SLE patients is difficult to estimate because national cancer registries often do not record malignancies in situ. Cervical cancer remains an important issue for women with SLE, and an increased risk may come about for different reasons, including (1) reduced clearance of human papillomavirus (HPV), the causal agent in most cases of cervical cancer; (2) increased risks of cervical cancer associated with immunosuppressive medications; and (3) reduced rates of routine Pap smears and other screening procedures in a population of patients with chronic illnesses. In the large multinational study performed more recently, the SIR for invasive cervical cancer was found to be elevated at 1.26, albeit with confidence intervals that cross the null.222 Other studies have confirmed increased risks of abnormal Pap smears and cervical dysplasia in women with SLE.229,230 Different studies have implicated increased prevalence of HPV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases,230–233 and immunosuppression232–235 may partly explain this association. As with mammography, women with SLE seem less likely to undergo routine Pap testing than women in the general population.236,237

Several studies have identified a link between SLE and the development of lung cancer.225 Indeed, the largest multinational cohort of SLE subjects found an increased incidence of lung cancer compared with the general population (SIR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.76).222 Further analyses of the cases of lung cancer in this cohort revealed a variety of tumor types, including adenocarcinoma, bronchoalveolar carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and carcinoid tumor.238 Most cases (71%) occurred in smokers, 25% of cases were in men, and few (20%) had previous exposure to immunosuppressive agents.238 To date, no particular demographic or clinical features have been found to explain this apparently increased risk.

Overall, the presence of SLE seems to carry a small increased risk for the development of cancer, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lung cancer, and cervical cancer. The underlying causes of these associations are unknown, but they do not seem to be exclusively related to the use of immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents.* Data suggest that lupus patients may be less likely to receive recommended cancer screening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree