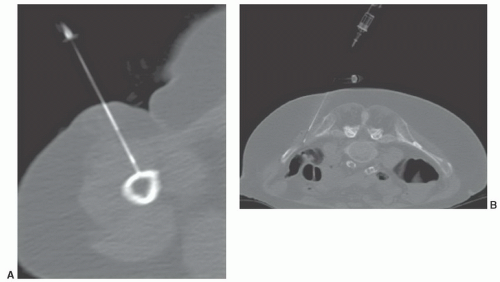

but scored at 4). MRI is also scored at 9 if radiographs are suspicious for malignancy with CT scored at 5 and FDG-PET imaging also scored at 5.10 CT is still recommended if osteoid osteoma is suspected (scored 9 with bone scans as an alternative and scored 6 of 9).10

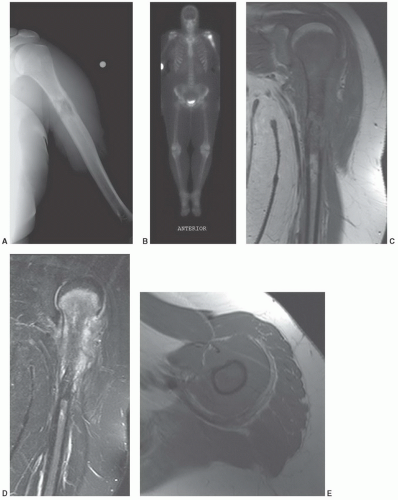

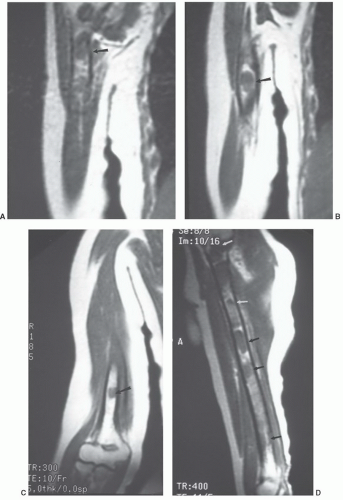

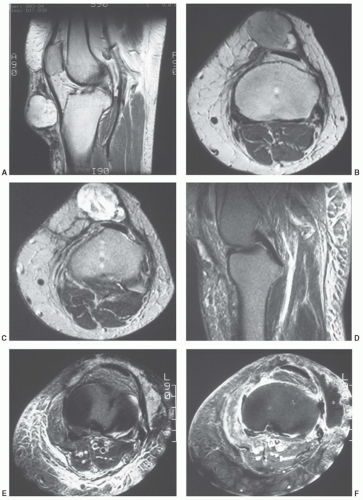

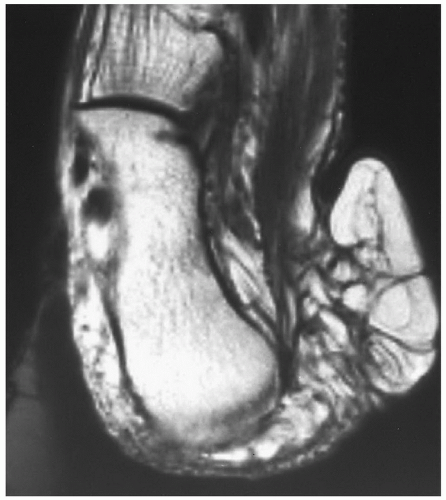

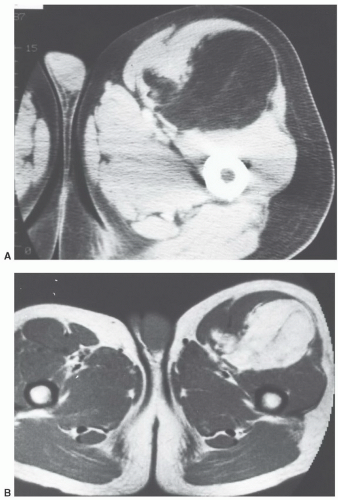

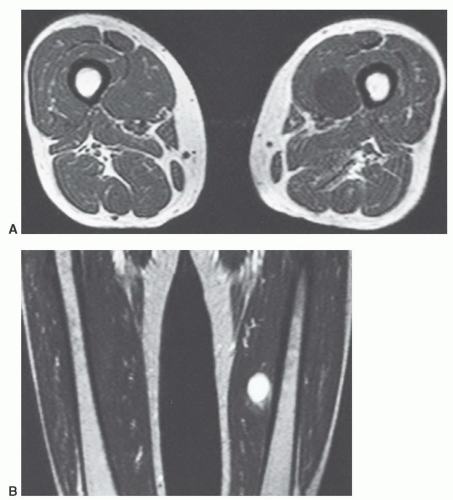

additional imaging plane or planes will vary with the involved body part, the lesion location, and its relationship to crucial structures. In general, the additional plane is sagittal with anterior or posterior masses and coronal with medial or lateral lesions. Oblique planes may also be a useful adjunct to reduce the problems from partial volume effects (Figs. 12.4 and 12.5). In these additional planes, a combination of conventional T1- and T2-weighted spin-echo (SE) images, turbo (fast) spin-echo images, gradient images, and STIR imaging is useful, as the cases require.

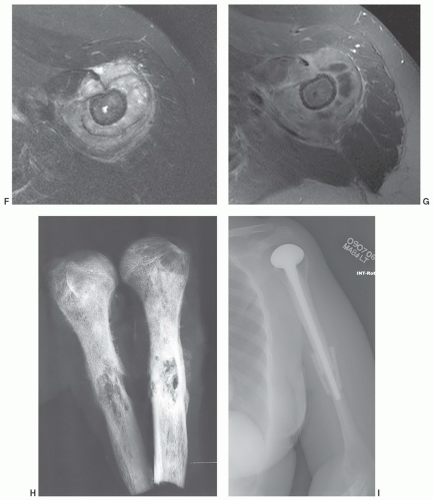

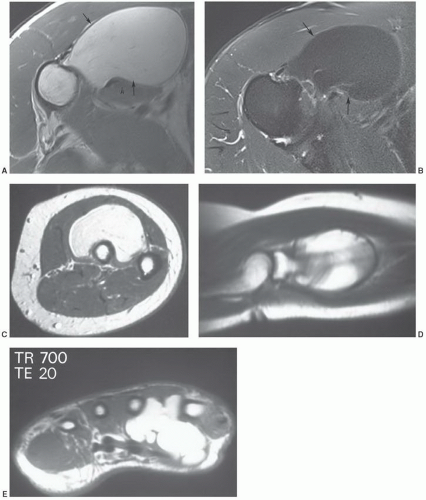

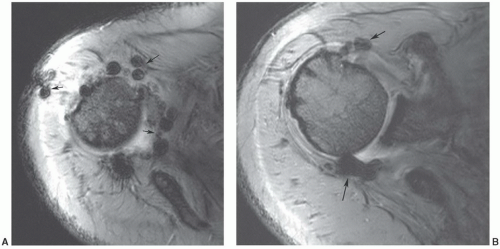

Figure 12.7 Gradient-echo axial images of the shoulder (A and B) following rotator cuff repair. There are multiple blooming artifacts (arrows) due to metal debris. |

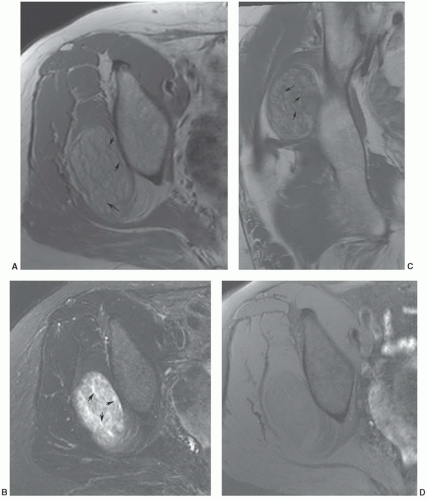

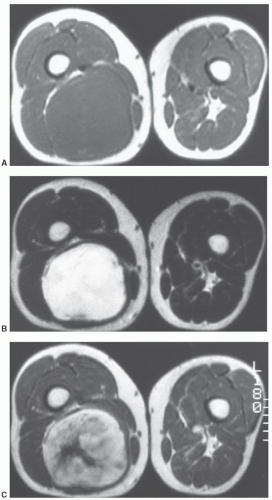

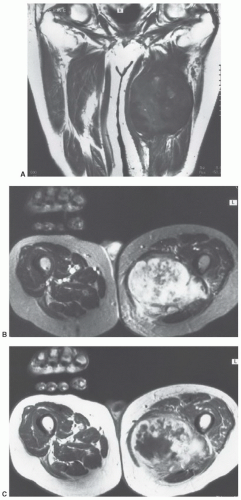

malignant lesions.30,32 Dynamic studies using fast scan techniques were initially reported by Erlemann et al.27,28 Others have also studied these techniques, but with inconsistent results. In our practice, we reserve the use of dynamic gadolinium studies for selected cases (see below, limitations of MRI) (Figs. 12.8 and 12.9).

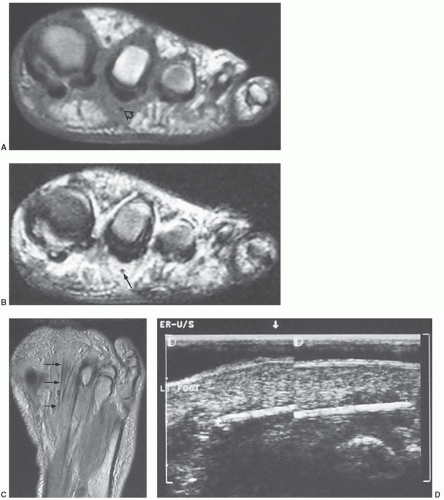

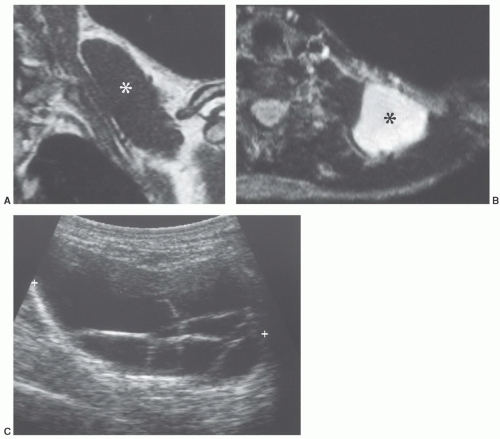

MR images will show the changes associated with the foreign body, although the foreign body itself may have no signal and may be difficult to identify. We have found ultrasound a useful adjunct in such cases (Fig. 12.10).40

Table 12.1 Enneking System: Staging of Musculoskeletal Neoplasms | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

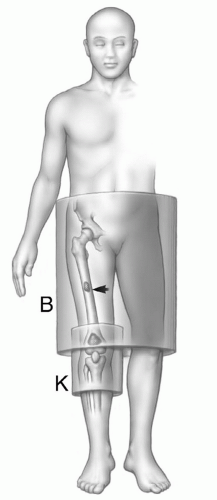

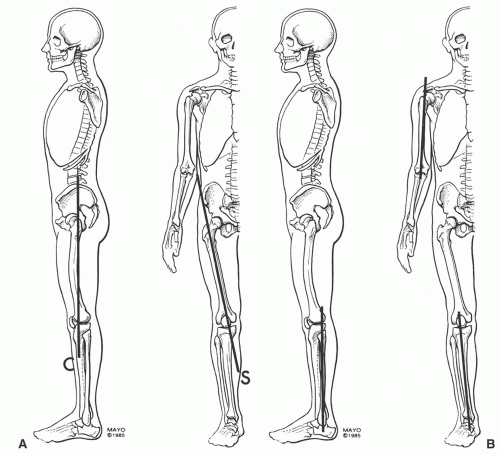

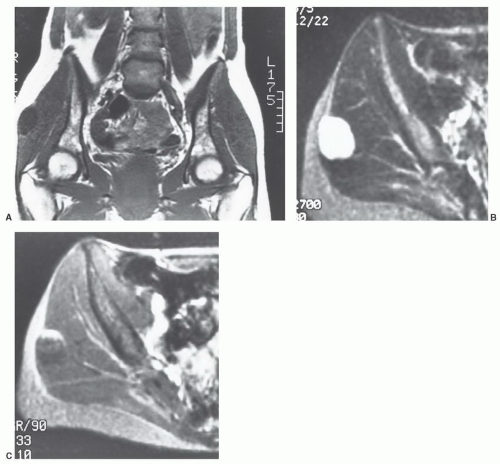

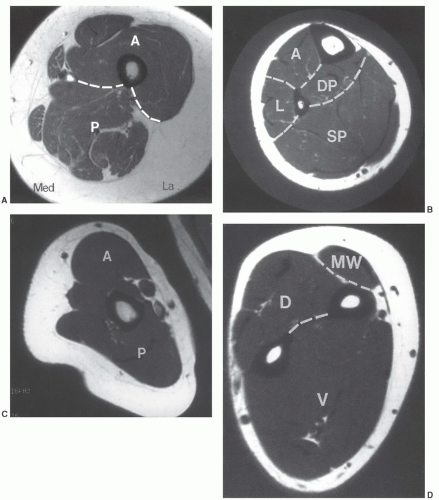

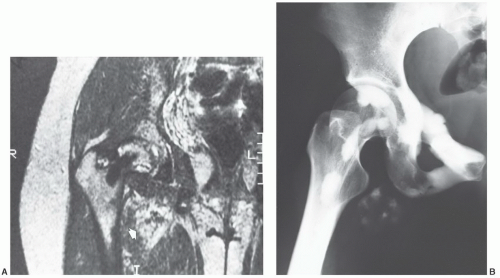

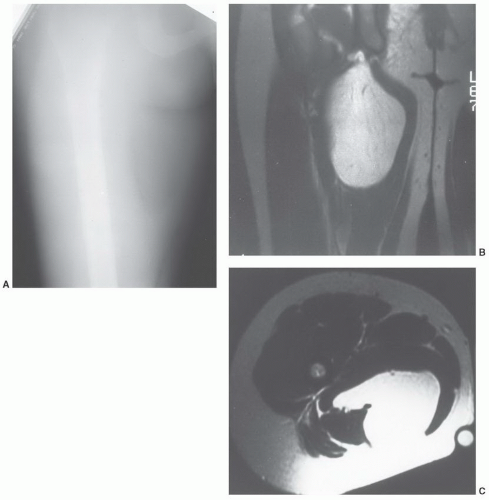

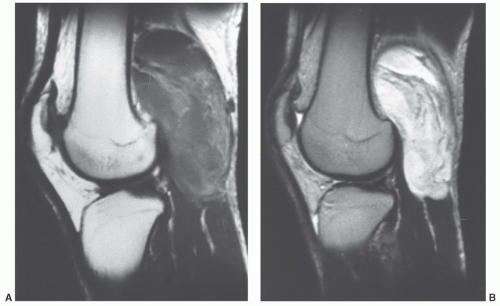

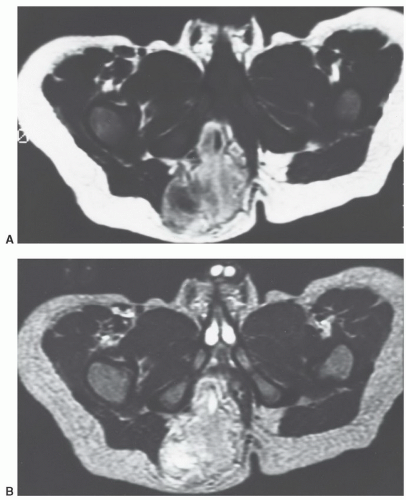

MRIis the technique of choice for detection and local staging of soft tissue lesions. Certain benign lesions, such as lipomas, myxomas, hemangiomas, and cysts have characteristic appearances that may obviate the need for biopsy or surgical intervention (Fig. 12.13). Malignant or indeterminate lesions are evaluated using T1- and T2-weighted conventional or fast spin-echo sequences with or without fat suppression. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images are also obtained. Two image planes are necessary to fully evaluate the extent, compartment, and neurovascular involvement (Fig. 12.3). Dynamic gadolinium techniques may be of value for differentiating benign form malignant lesions. Angiography is not often performed, but can be used for indications noted above.

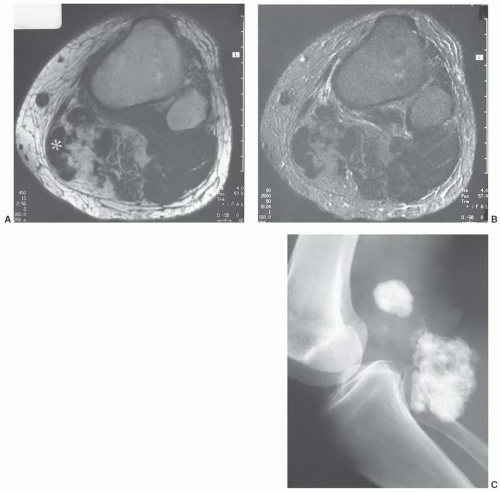

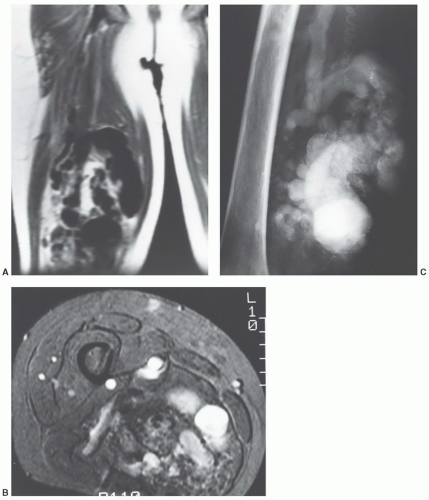

an underlying skeletal deformity (such as exuberant callus related to prior trauma) or bony exostosis that may masquerade as a soft tissue mass. Radiographs may also reveal the presence and nature of soft tissue calcifications, which can be suggestive and at times very characteristic of a specific diagnosis. For example, they may reveal the phleboliths within a hemangioma, the juxta-articular osteocartilaginous masses of synovial osteochondromatosis, the peripherally more mature ossification of myositis ossificans, or the characteristic bone changes of other processes with associated soft tissue involvement (Fig. 12.15).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

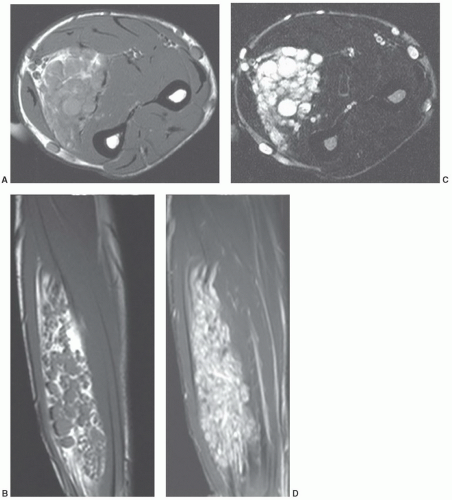

of pulse sequence (Fig. 12.17).59,60,61,62,70 When significant fibrous tissue is present, these lesions may be termed fibrolipomas. It is important to remember that when a fatty lesion does not meet the imaging requirements for a lipoma, liposarcoma is typically the diagnosis of exclusion; however, lipoma variants are encountered more commonly than liposarcoma.59,71

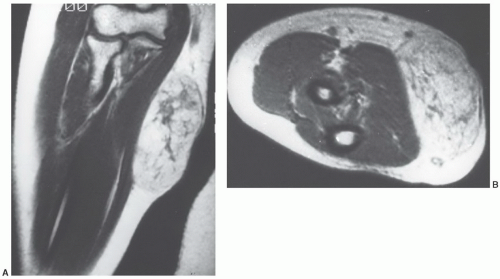

tissues; however, involvement isolated to the intermuscular region (intermuscular lipoma) is less common. Intramuscular lipoma occurs in patients of all ages but predominantly in adults, with most cases presenting in patients between 30 and 60 years of age.52 There is a slight male predominance. Patients typically present with a mass in the large muscles of the extremities, especially the thigh, shoulder, and upper arm. The fat within the intramuscular lipoma may infiltrate between skeletal muscle fibers, giving the intramuscular lipoma a striated appearance on gross inspection.

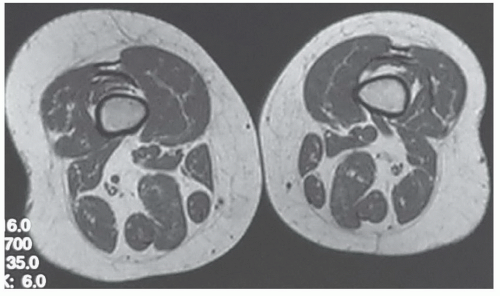

MRI as a predominantly fatty mass (with signal intensity equal to that of the subcutaneous fat), infiltrating the adjacent skeletal muscle. The mass is usually well defined and sharply circumscribed, with imaging characteristics similar to that of an “ordinary lipoma.” This lesion has also been referred to as “infiltrating lipoma.” Despite being well-defined radiologically, margins are frequently infiltrating at microscopy, with adipose tissue intermingled with skeletal muscle fibers that are variably atrophic (Figs. 12.20 and 12.21). Matsumoto et al.75 reported the MR appearance of intramuscular lipoma in 17 cases and found the lesion to be homogeneously pure fatty tissue in 12 (71%), with the remainder being fat with intermingled muscle fibers, the latter showing a signal intensity identical to that of skeletal muscle on T1- and T2-weighted pulse sequences. An infiltrative margin was seen in 7 cases (41%).

and foot. Lipoma arborescens usually involves the knee.60,76 About 20% of the time, knee involvement is bilateral.77

hamartoma of nerve, perineural lipoma, fatty infiltration of the nerve, and intraneural lipoma.80,81 The term “neural fibrolipoma” was originally preferred because it better describes the underlying pathology.80 More recently, the WHO has adopted the term lipomatosis of nerve.62 The cause of this disorder remains unclear; it may be related to hypertrophy of mature fat and fibroblasts in the epineurium.81

appearing as a tan yellow mass within the nerve sheath.84 Microscopy demonstrates infiltration of the epineurium and perineurium by fibrofatty tissue.81 Cases in which there is macrodactyly are histologically indistinguishable from those in which there is no macrodactyly.81

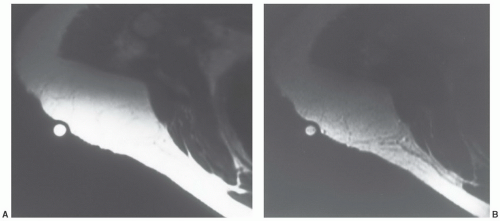

mass.86 The adjacent bone may demonstrate solid periosteal reaction, cortical thickening, saucerization, or osseous excrescences.68,91 Osseous changes are seen in 67% to 100% of cases,68,91,92 although these may be subtle. The periosteal reaction in two cases reported by Murphey et al.91 was minimal, being identified only on magnification radiography. The osseous excrescences do not demonstrate the cortical and medullary continuity or hyaline cartilaginous cap seen with a true osteochondroma.68

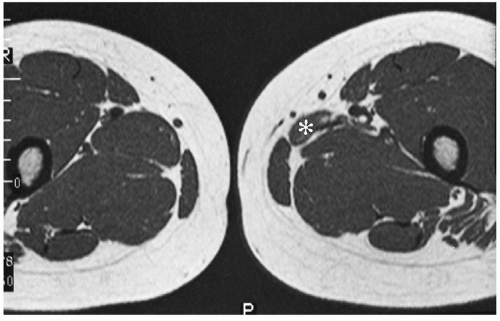

that adult cases represent delayed presentation. Diffuse lipomatosis typically affects the limbs, although involvement of the trunk and chest wall may be seen.93 Lipomatosis may be associated with coexistent osseous hypertrophy, but unlike macrodystrophia lipomatosa, the nerve is unaffectedand the disease is not confined to an extremity. Reported as rare,52 we believe that mild cases of lipomatosis are not uncommon and may be easily overlooked (Fig. 12.6).

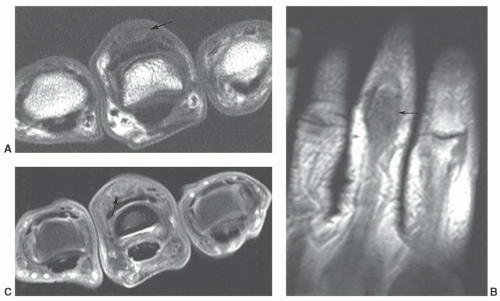

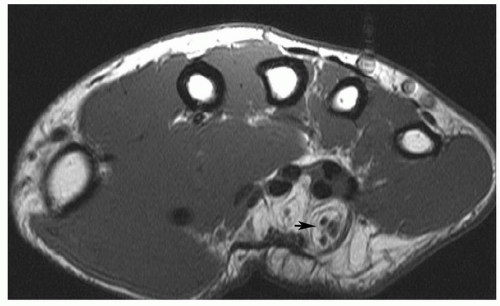

Figure 12.24 Neural fibrolipoma. Axial T1-weighted image of the wrist demonstrating a fibrolipoma of the ulnar nerve (arrow). |

recurrence and metastasis. While the round cell liposarcoma was previously identified as distinct subtypes by the WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumors, the myxoid and round-cell liposarcoma are now combined under the designation of myxoid liposarcoma.62 These lesions were known to form a histological continuum, and represented the ends of a common spectrum.58 Now under a single diagnosis, the pure myxoid lesion is considered an intermediate grade tumor at the low-grade end of this spectrum, while the hypercellular (round cell) morphology represents the histologically similar, high-grade counterpart. The presence of the hypercellular component is associated with a more aggressive clinical course and a significantly worse prognosis.95 Well-differentiated liposarcomas are most common, accounting for about 54% of all classified liposarcomas. Myxoid liposarcoma is next most common,

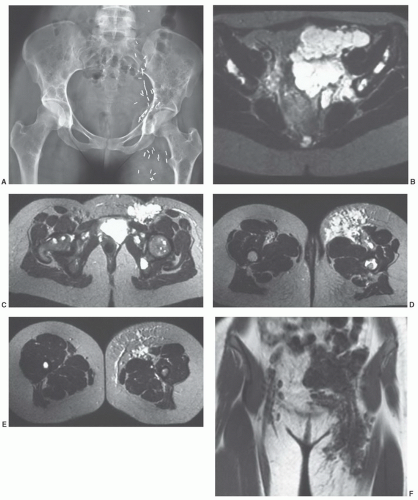

accounting for 28%, followed by dedifferentiated (10%), and pleomorphic liposarcomas.96 Liposarcomas tend to occur in both the retroperitoneum and extremities, with extremity lesions presenting about 10 years earlier than those in the retroperitoneum. Dedifferentiated liposarcomas are most common in the retroperitoneum, whereas the other subtypes are more common in the extremities.96

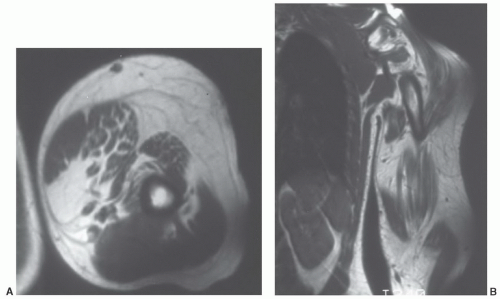

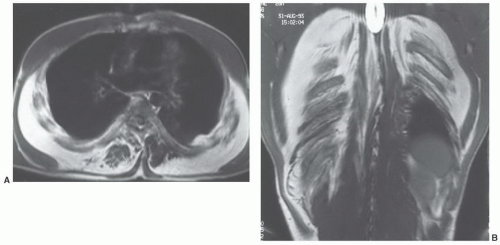

Figure 12.26 Upper extremity lipomatosis in a 23-year-old man. Axial (A) and coronal (B) T1-weighted SE MR images of the left upper extremity show diffuse overgrowth of adipose tissue. |

Figure 12.27 Symmetric lipomatosis in a 28-year-old man. Axial (A) and coronal (B) T1-weighted MR images show extensive, but symmetric, lipomatosis of the chest wall. |

from a well-differentiated liposarcoma, lipoma variants occur with an imaging appearance that will overlap that of a well-differentiated liposarcoma. The distinction of lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma is simple when the former is homogeneous with an imaging appearance identical to that of the subcutaneous adipose tissue. When nonadipose elements are present, however, this distinction may be quite problematic. Recent literature has documented awider spectrum for the imaging features of lipoma than had been previously appreciated, with a small but significant number of lipomas demonstrating prominent nonadipose areas and an imaging and appearance that may mimic that traditionally ascribed to well-differentiated liposarcoma.96 In these cases, the nonadipose areas represent fat necrosis and associated calcification, fibrosis, inflammation, and myxoid change. As a generalization, lesion size may also be useful, in that well-differentiated liposarcoma tends to be significantly larger than lipoma. In a recent review of 60 well-differentiated fatty tumors, the average largest dimension of malignant lesions was nearly twice that of benign lipomas (24 cm vs. 13 cm).96 Enhancement pattern may also be useful, with well-differentiated tumors showing contrast enhancement.98 Kransdorf et al.,61 noted that statistically significant features of liposarcoma included lesions more than 10 cm in size (p <.001), thick septa (p = .001), lesion less than 75% fatty tissue (p <.001), and globular or nodular areas of non-fatty tissue.61

histologically indistinguishable, and the term “atypical lipoma” has been advocated by some to spare the patient a malignant diagnosis and prevent unnecessary radical surgery for well-differentiated lipomatous tumors of the extremity. However, other investigators prefer the term “well-differentiated liposarcoma” for deep fatty tumors of the extremities because of the propensity of these tumors to recur and because of the remote possibility of dedifferentiation; either de novo or in recurrences. One could theoretically categorize both atypical lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma as atypical lipomatous tumors, because both have a propensity to recur locally but no tendency to metastasize.99 Lesions with similar histology in the retroperitoneum have retained the designation of well-differentiated liposarcoma because of their association with multiple local recurrences (presumably because they are frequently incompletely resected) and because such lesions may eventually be fatal.102,103,104,105

lesions in the deep somatic soft tissues, we would agree with Weiss and Goldblum and use the term “atypical lipoma” only for subcutaneous extremity lesions, reserving the term “well-differentiated liposarcoma” for lesions with similar histologies in all remaining sites.52,58

Weiss authored by Weiss and Goldblum121 have devised a more anatomic approach to benign vascular lesions. The subtypes include synovial hemangiomas arising in the synovium, intramuscular which is a proliferation of benign vessels in muscle, venous hemangiomas, and arteriovenous hemangiomas with shunts and a mix of venous and arterial structures.118,119,120,121 Other categories include the epithelioid hemangioma, a feeding artery, and well-defined mature vessel lined by epithelioid endothelial cells and stroma mimicking lymph nodes.118 Angiomatosis is another category with a diffuse hemangioma affecting large anatomic regions that crosses tissue planes and compartments.118,122

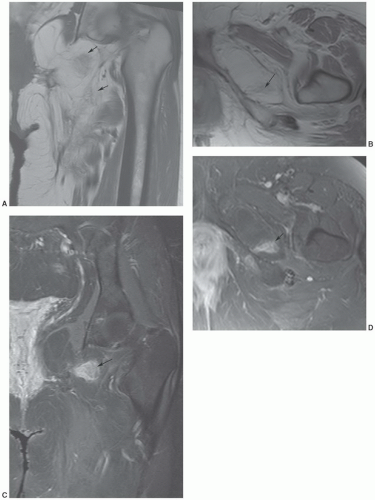

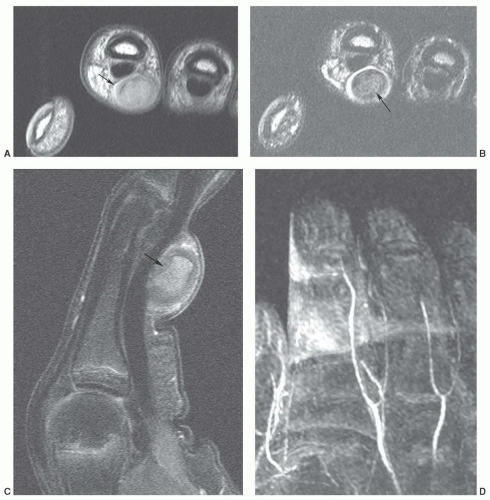

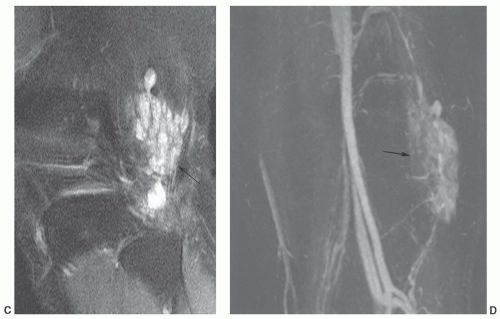

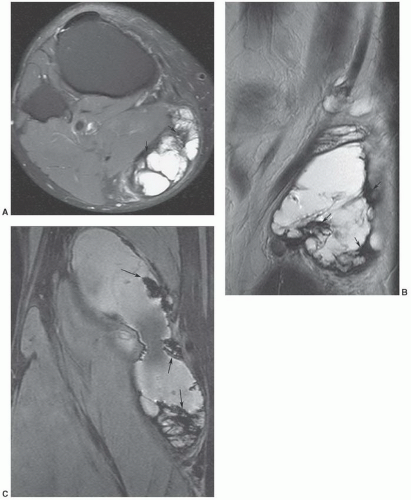

compared with subcutaneous fat (Fig. 12.41).125,128 Segments of the lesion are isointense to either fat and/or muscle. MR angiography is useful for evaluation of the vascular supply of the lesion (Fig. 12.41). Phleboliths (within the hemangioma) may be detected as small rounded areas of signal void on MRI, but these are more readily apparent on radiographs or CT.116 Marrow signal abnormalities may be seen adjacent to large hemangiomas. Although their nature is not known, they are hypothesized to represent either marrow edema or hematopoietic conversion with localized hyperemia.126

of congenital obstruction of lymphatic drainage.138,139 Its progressive nature, however, has suggested that it may be a benign mesenchymal neoplasm.136

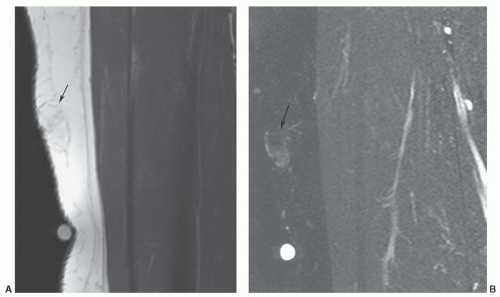

Figure 12.42 Superficial angiolipoma in the thigh. Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighted images (B) demonstrate the subtle angiolipoma (arrow). |

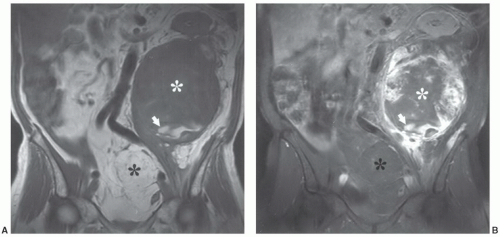

large uniloculated or multiloculated cystic spaces, lined by lymphatic endothelium.136,141 It contains serous or chylous fluid.137 Cystic lymphangiomas are most common in the neck (typically in the posterior cervical space) and axilla, with these locations accounting for 75% and 20% of lesions, respectively.142,143 The prevalence of these locations has been suggested to be the result of sequestered lymphatic anlage, which lack adequate drainage. Other rare locations include the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, bone, omentum, and mesentery.143 Up to 10% of cervical cystic lymphangiomas will extend into the mediastinum.144 Cystic lesions (cystic hygromas) are typically found in regions in which the loose fatty connective tissue allows relatively unlimited growth.139,141 The overwhelming majority of lesions present in children, with more than half presenting at birth and 90% discovered by the age of 2 years.136,137,144,145,146 Fewer than 10% are found in adults.141 Retroperitoneal cystic lymphangiomas are usually found in older children and adults. Acute symptoms result from infection, rupture, hemorrhage, or pressure on adjacent structures.137 Cystic lymphangiomas are usually isolated lesions, although posterior neck cystic lymphangiomas may be associated with Turner syndrome.147

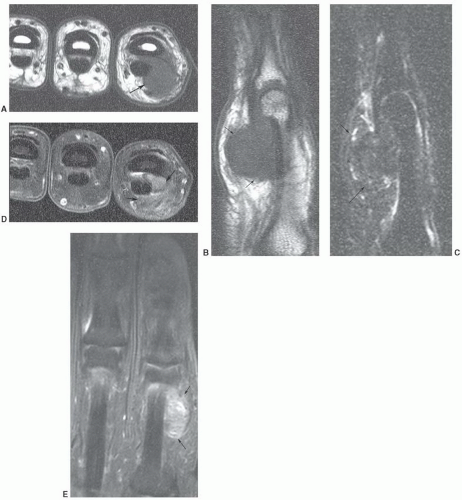

Multiple lesions are unusual but have been reported.153 Local recurrence is not uncommon and may be seen in approximately 9% to 20% of cases.153,156 A malignant giant cell tumor of tendon sheath with metastases was reported by Carstens and Howell158; however, such lesions are quite rare.

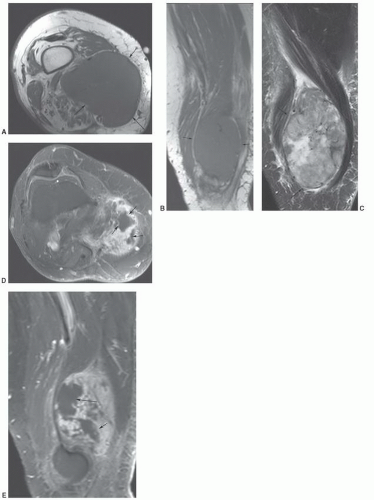

of histiocytic-fibroblastic-myofibroblastic lesions.161,162 Maluf et al.161 noted that the lesions have an overlapping clinical presentation, with similar patient age and gender as well as lesion location and distribution. In addition, these lesions share similar growth patterns, showing a lobulated architecture. Although the microscopic appearance varies, both lesions contain spindle cells and multinucleated giant cells and share similar immunohistochemical attributes. Hence, the fibroma and giant cell tumor of tendon sheath may represent end points of a spectrum of cellular proliferation.162,163 It has been our experience that these lesions will show a similar appearance atMRI (Fig. 12.47).163

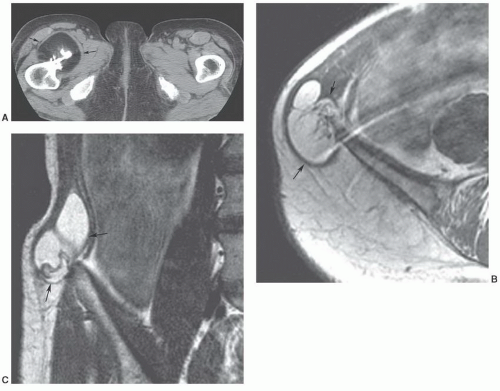

the knee (26%).164 Bone erosive changes are usually geographic lytic lesions with well-defined thinly sclerotic margins. They are most characteristic when they are multiple and are seen on both sides of the joint. The joint space is usually preserved, as is bone density.164 Uncommonly, radiographs will demonstrate an osteoarthritis appearance, with typical osteophytes, sclerosis, cysts, and joint narrowing, or an arthritis-like appearance, with concentric joint space loss, osteoporosis, and erosions.167 Radiologic calcification within the mass has been reported174 but is extremely

unusual and should suggest an alternative diagnosis. Calcification has also been reported in diffuse giant cell tumor of tendon sheath.175

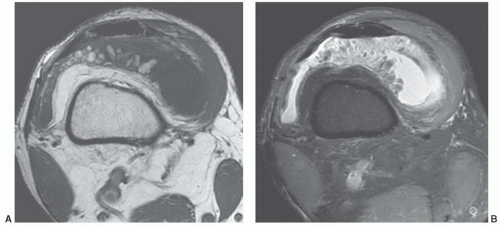

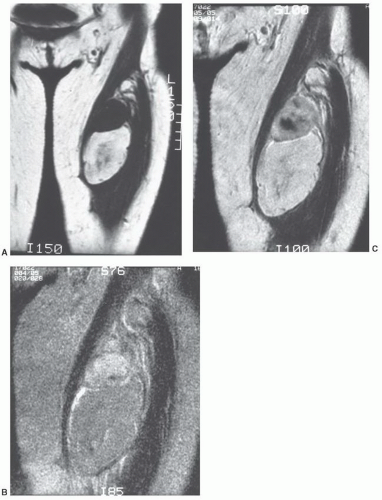

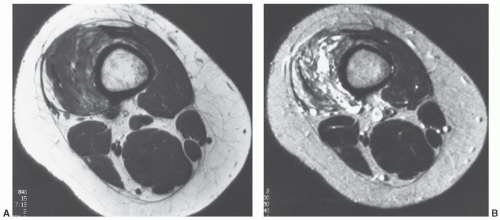

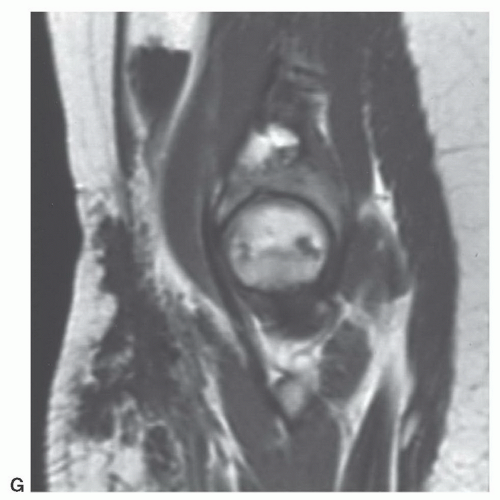

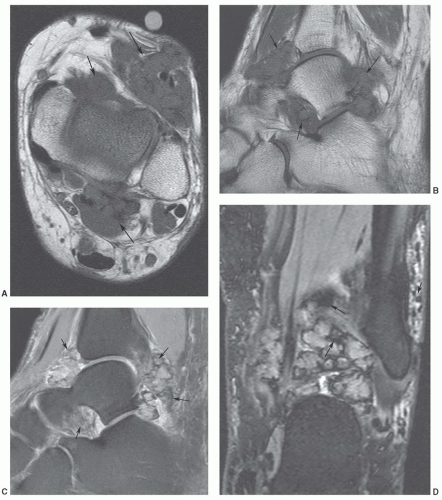

synovial inflammation and proliferation.152,169 The lytic bone lesions seen on radiographs and joint effusions are typically seen well on MRI.152 The diffuse giant cell tumor of tendon sheath has a skeletal distribution similar to that of PVNS and is often considered an extra-articular extension of PVNS. Its MRI signal intensity characteristics are similar to PVNS (Fig. 12.49).

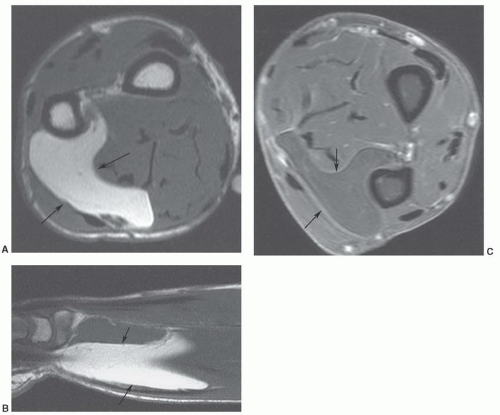

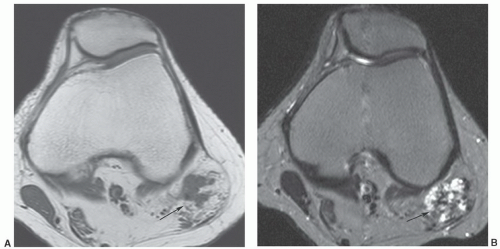

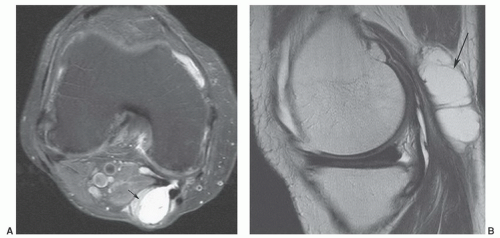

Figure 12.50 Popliteal cyst. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) fat-suppressed proton density-weighted images demonstrating fluid extending into the gastrocnemius semimembranosus bursa (arrow). |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree