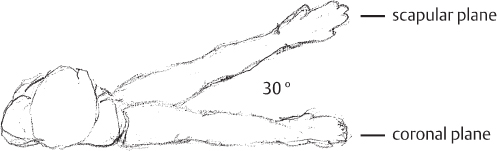

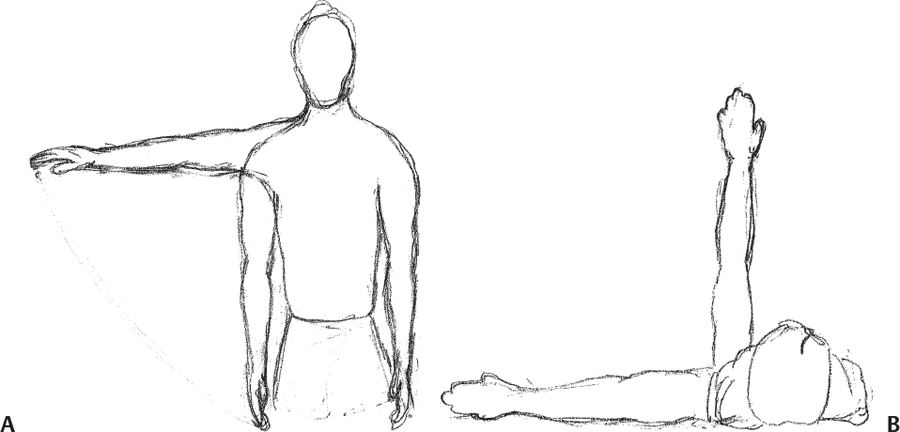

II 7. Modification of Traditional Exercises for Shoulder Rehabilitation and a Return-to-Lifting Program 8. Use of Taping and External Devices in Shoulder Rehabilitation 9. Use of Interval Return Programs for Shoulder Rehabilitation Jake Bleacher and Todd S. Ellenbecker Traditional upper-body weightlifting exercises such as the bench press, military press, and latissimus dorsi (lat) pull-downs are just a few of the regularly performed resistance exercises included in many training programs utilized by the recreational weightlifter, bodybuilder, or competitive athlete to enhance strength, performance, body composition, and aesthetics. The unique anatomy and biomechanics of the shoulder girdle present an increased risk of injury with many of the traditional weightlifting exercises, which exceed the mobility and stability requirements of the shoulder complex.1 Although many of these exercises are recognized by physical therapists and athletic trainers as inappropriate during shoulder rehabilitation, many patients hope to return to performing these exercises at some point following their recovery from shoulder injury or surgery. Furthermore, high resistance, low-repetition formats using traditional weight-lifting exercises are not a recommended component of rehabilitation programs but do form the mainstay of many strength and conditioning programs for athletes.2 During rehabilitation of the shoulder following injury or surgery, patients whose primary recreational activity involves traditional weightlifting at the local gym must be given some exercise guidance and parameters to prevent reinjury and allow a continued exercise program for general health and performance enhancement. In this chapter, we will give an overview of the specific stresses on the human shoulder inherent in many traditional weightlifting exercises and provide modifications to these exercises to protect the static and dynamic stabilizing structures. We will also outline specific strategies and concepts for patients following shoulder injury and/or surgical procedures such as rotator cuff tendonitis, acromioclavicular (AC) joint pathology, gleno-humeral (GH) joint instability, and labral repair. Although many stresses are indeed present during the performance of upper-extremity resisted exercise, we will focus on the impingement stresses inherent in exercises using overhead positioning, as well as the tensile loading to the GH joint capsular ligaments during performance of movements or exercises behind the scapular and coronal planes of the body. The stresses inherent in traditional weight-lifting exercise can exaggerate the compressive forces against the undersurface of the acromion outlined by Wuelker et al.3 Many traditional exercises such as the lateral raise, triceps pullover, and military press utilize ranges of motion (ROM) with greater than 90 degrees of elevation. Wuelker et al3 found that peak subacromial forces occur between 85 and 120 degrees, with peak forces estimated at 0.42 times body weight or 10.2 times the weight of the upper extremity in unloaded conditions.4 These stresses are magnified in the presence of subacromial spurs, AC injury, and acromial types II and III, which increase the incidence of rotator cuff tears5,6 and can be present in the skeletally mature weightlifter presenting with shoulder pain. Additionally, many traditional resistance exercises used by weightlifters and body builders place large stresses on the anterior glenohumeral ligament complex.1,7 The anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament is an important structure responsible for stabilizing against anterior, posterior, and inferior GH translation with 90 degrees of GH abduction.7 The stresses on this structure are increased during exercise movements that place the shoulder behind the coronal plane of the body (Fig. 7-1) such as the end-range descent phase of the bench press, the pushup, the pec deck, as well as during the behind-the-head lat pull-down, and during exercises such as the dip and behind-the-head overhead shoulder press. Fees et al2 have termed the abduction external rotation (ER) position inherent in many of these aforementioned exercises as the high-five position and have recommended modifications to this position for patients returning to traditional weightlifting programs following injury or surgery as well as for high-risk groups, which include overhead athletes and those with underlying GH joint hypermobility. Many of the traditional overhead pushing and pulling lifts (military press, pull-downs, chin-ups, deltoid laterals) cause an increased stress to the inferior and anterior portion of the GH capsule and ligaments, along with an increased risk of subacromial impingement. Overhead lifting movements that position the shoulder in end-range abduction increase the stress to the static stabilizers of the shoulder, while at the same time decreasing the mechanical efficiency of the dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder girdle.8 The mechanical disadvantage in these end-range overhead positions is because of a decrease in the anatomic length-tension relationship of the shoulder abductors and rotators with the scapular stabilizers. This less-than-optimal relationship between the dynamic stabilizing muscles of the shoulder and scapular muscles places increased demands on the static and dynamic stabilizers, and attenuation of these structures should stability requirements not be met.9 The scapular plane position, which is 30 to 45 degrees anterior to the coronal plane, reorients the humerus and scapula to a more advantageous position (Fig. 7-2).10 The scapular plane position of the shoulder reduces the capsuloliga-mentous stress and creates an optimal anatomic length-tension relationship for the scapular and rotator cuff muscles.11 Figure 7-2 Glenohumeral joint abduction in the scapular and coronal planes. (Figure 7-2 courtesy of Veronica Serna.) There is a greater risk for injuries to the shoulder than in other large synovial joints such as the hip and knee because of the inherent instability of the GH joint, which is characterized by incongruity of the articulating surfaces and lack of osseous stability.8 Coupled with the excessive range of motion afforded to the shoulder complex, there exists a vulnerability to the static and dynamic restraints in the shoulder when the arm is loaded with resistance beyond optimal anatomic safe zones. The safe zone, as identified by the second author9 in the development of an upper-extremity tennis conditioning program, consists of performing resistive exercises below shoulder level (90 degrees of shoulder elevation) and anterior to the coronal plane (optimally the scapular plane) to minimize subacromial impingement and prevent abnormal stress to the anterior GH joint capsule and capsular ligaments (Fig. 7-3).2 In the remainder of this chapter, we will identify traditional weightlifting exercises that are potentially harmful to a patient recovering from a shoulder injury, and suggest modifications to traditional exercise(s) to gain the benefit of stressing the targeted muscle without placing undue strain on the stabilizing structures of the shoulder. Specific recommendations are given for each exercise along with detailed photos to facilitate the proper application of the exercise modifications. Figure 7-3 Safe-zone general guideline depicting range of motion limitation for modification of traditional weightlifting exercises. (Figure 7-3 courtesy of Veronica Serna.) It is assumed that the patient or individual for whom these exercises are intended has reached a level of recovery and function, particularly acceptable levels of rotator cuff and scapular strength, endurance, and optimal external-internal rotation balance and force couple relationships. The treating physician or the appropriate rehabilitation personnel should discuss with the patient and approve any resumption of an exercise program, particularly weightlifting or sports activities. Before individually covering specific weightlifting exercises and movement patterns, we will review several concepts in relation to grip position and hand placement that apply to many traditional weightlifting exercises. In addition to maintaining the shoulder in a position near the scapular plane, other components of a lift, such as the hand spacing and grip type (overhand, underhand, and neutral rotation) can be modified to decrease shoulder torque and tendon impingement. In general, hand placement is typically gauged relative to the width between the lifter’s acromion process. Wider hand spacing (>1.5 × shoulder or biacromial distance) (Fig. 7-4) for traditional lifts such as the flat, incline, and decline bench press, military press, barbell squats, and pull-downs are generally not recommended in patients with either anterior shoulder instability or subacromial impingement and rotator cuff pathology because of the increased stability requirements and torque generated at the shoulder.2,12 When the rotator cuff is either compromised or has insufficient strength, there is a greater likelihood of GH instability when greater demands are placed on the dynamic stabilizers and they are not met. To minimize this stress, hand spacing should be no greater than 1.5 × the biacromial width, unless there is evidence of posterior shoulder instability. In patients with posterior instability, it is generally recommended to utilize wider hand spacing to limit the stress on the posterior restraints (hand spacing greater than 1.5 × the biacromial width) (Fig. 7-5). The wider hand spacing allows for better approximation of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa.2 The actual grip type will also affect subacromial spacing for the supraspinatus and long head of the biceps tendon. Consideration of the type of pathology present will affect grip selection. The overhand (fully pronated forearm) grip (Fig. 7-6) will remove the long head of the biceps from below the acromion because of the internally rotated position of the humerus, but at the same time will draw the supraspinatus tendon under the acromion.2 This overhand position can cause tethering of the supraspinatus tendon if a hooked acromion or primary impingement is present. Using the overhand grip will place the biceps tendon in a position where it will be less likely to be contacted under the acromion.13,14 The underhand grip (fully supinated forearm) (Fig. 7-7) allows the supraspinatus to be drawn outside of the subacromial space, but at the same time brings the tendinous portion of the long head of the biceps tendon under the acromion; this may cause impingement of the long head of the biceps tendon.2 A neutral hand positioning (forearms resting in neutral pronation and supination) allows for a more anatomically optimal relationship for the tendinous attachments to the anterolateral humeral head when the arm spacing is shoulder-width apart. This neutral forearm position is possible with dumbbells (Figs. 7-8 and 7-9) or on weight machines designed with variable grip types. Additional grip modifications are pictured in Figures 7-10 and 7-11 for the seated row and lat pull-down, respectively. Figure 7-4 Bench press exercise with hand spacing 1.5 × the biacromial width. This position is recommended for individuals with a history of rotator cuff pathology and anterior glenohumeral joint instability. Figure 7-5 Bench press exercise with hand spacing >1.5 × the biacromial width. This hand position would be recommended for individuals with a history of posterior glenohumeral joint instability. Figure 7-6 Bench press with traditional overhand or pronated grip. Figure 7-7 Bench press with underhand or supinated grip. Figure 7-8 Photo of dumbbell bench press with neutral forearm grip. Figure 7-9 Photo of dumbbell shoulder press with neutral forearm grip. Tables 7-1 to 7-5 provide summaries of the recommended modifications of traditional weightlifting exercises, which are based on the anatomic and biomechanical concepts discussed in this chapter. They provide the clinician or therapist with an objective guide to returning a patient to traditional weightlifting exercises. The bench press, of all the chest exercises is one of the most widely used for developing and measuring upper-body strength and performance.15 Because of the importance of the bench press exercise to weightlifters and many athletes, modifications to various elements of the exercise are necessary for those who are recovering from shoulder injury or surgery. Modifications to resistance, hand spacing, grip selection, and ROM in the GH joint are needed to minimize excess strain to the static and dynamic structures of the shoulder (Table 7-1). Early focus should be on adhering to correct form with lighter resistance and higher repetitions (12 to 15 RM loads). As mentioned in a previous section, hand spacing should be slightly wider than shoulder width apart (1 to 1.5 × biacromial width) with grip type (overhand, underhand, and neutral) varied based on the type of underlying pathology.

Special Topics in Shoulder

Rehabilitation

7

Modification of Traditional Exercises for Shoulder Rehabilitation and a Return-to-Lifting Program

Anatomic and Biomechanical Rationale for Range-of-Motion Limitation in Traditional Upper-Extremity Resistive Exercise

General Strategies to Protect the Shoulder during Weightlifting Exercises

Specific Concepts for Modification of Weightlifting Exercises

The Bench Press

The Cable Fly, the Pec Deck, the Dumbbell Fly, and the Pushup

The Shoulder Press

Lateral Raises and Upright Rows

Bent-over Rows

Overhead Triceps Extension and Dips

Lattisimus Dorsi Pull-Downs

Behind-the-Back Squats

Stresses on the Shoulder of Traditional Upper-Extremity Resistive Exercise

Stresses on the Shoulder of Traditional Upper-Extremity Resistive Exercise

Anatomic and Biomechanical Rationale for Range-of-Motion Limitation in Traditional Upper-Extremity Resistive Exercise

General Strategies to Protect the Shoulder during Weightlifting Exercises

Specific Concepts for Modification of Weightlifting Exercises

Modifications of Specific Weightlifting Exercises

Modifications of Specific Weightlifting Exercises

The Bench Press

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree