8 Anna E. Thatcher and George J. Davies The glenohumeral (GH) joint is an inherently unstable joint and injuries are often related to or result in a decrease in joint stability. Many of the shoulder pathologies discussed in this book are influenced by improper GH and scapulothoracic (ST) biomechanics. In addition to the strengthening and proprioceptive exercises discussed in previous chapters, external devices such as taping and bracing are used clinically in an attempt to increase shoulder stability and improve function. The lack of stable structures in the shoulder joint makes it more difficult to stabilize with tape or a brace than the knee and ankle joints. Compared with the studies on taping and bracing lower extremity joints,1–5 there is considerably less research on taping and bracing the shoulder complex. In this chapter, we will summarize the current literature on the use of shoulder taping and bracing in the nonoperative treatment of shoulder pathologies. The purpose of taping is to provide protection and support for a joint while still allowing necessary movement for sport activities.6 Tape is believed to have both mechanical and proprioceptive effects that assist in improving shoulder stability, correcting faulty biomechanics and posture, and ultimately decreasing pain and increasing function. There are numerous clinical assumptions on why tape may be effective in decreasing subjective complaints of pain and increasing function (Table 8–1). According to Morrisey,7 taping methods may be used to inhibit or activate muscles. When tape is applied under tension in the direction of lengthened muscle fibers, it is thought to facilitate underlying muscle contraction by shortening the muscle. As the lengthened muscle becomes shortened, the length–tension relationship is optimized and maximal muscle contraction is possible.16 Tape applied to lengthen a shortened muscle is thought to inhibit the muscle. It is theorized tape may increase afferent input that will decrease volitional drive to the motor neuron pool from the descending pathways, resulting in muscle inhibition.8 Although taping may decrease subjective complaints of pain and improve function as a result of any combination of the above factors, much of the rationale for shoulder taping is based on anecdotal clinical reports.10–12,17–19 As discussed later in this chapter, there is no strong evidence to support shoulder taping in the current scientific literature.

Use of Taping and External Devices in Shoulder Rehabilitation

Clinical Rationale for the Use of Shoulder Taping

Methods of Shoulder Taping

Effectiveness of Shoulder Taping in Orthopaedic Conditions

Use of Shoulder Braces in Return to Athletic Activity

Evidence-Based Effectiveness of Shoulder Braces

Shoulder Taping

Shoulder Taping

Clinical Rationale for the Use of Shoulder Taping

|

Methods of Shoulder Taping

Clinicians use tape as an adjunct to other non-operative methods of treating various shoulder pathologies.10–12,17–19 Methods of shoulder taping have been described in the treatment of shoulder impingement,10,20 multidirectional instability11 and laxity,9 acromioclavicular (AC) joint sprains,19,20 GH subluxation due to underlying neurologic injury,21,22 and to improve posture.20,21 We will describe the use of tape in the treatment of multidirectional instability, anterior instability, scapular stabilization, and AC joint sprains.

General Taping Instructions

- Skin in the area to be taped is cleaned to remove any lotions, oils, etc. If desired, adhesive taping spray may be used.

- The patient sits in an upright posture with the scapula and GH joint actively or passively held in the desired position.

- An undertape (i.e., Hypafix; Smith & Nephew Healthcare Ltd., Hull, UK) is used to minimize skin irritation.

- A rigid tape (i.e., Leukotape; 3M, Maplewood, MN) is placed over the undertape. This tape is applied under tension in the desired direction to support the shoulder.

Multidirectional Shoulder Instability Taping Instructions

Three strips of tape are applied in an attempt to stabilize the GH joint. This taping procedure was used in the study by Hiltbrand et al9 and is pictured in Figure 8–1.

- Place a pillow under the arm to position the GH joint in slight abduction.

- Begin with tape over the anterior aspect of proximal humerus and pull superiorly, anchoring tape over the posterior shoulder.

- Place a second strip of tape over the middle aspect of the proximal humerus and anchor over the superior shoulder.

- The third strip of tape begins over the posterior aspect of the proximal humerus and ends over the anterosuperior shoulder.

Anterior Instability Taping Instructions

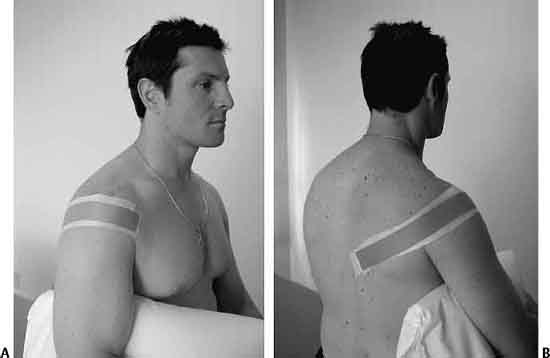

This taping procedure is used in patients with pathologies related to anterior instability. One or more strips of tape are applied in an attempt to stabilize the humeral head (Fig. 8-2).

- Begin by anchoring tape over anterior aspect of the humeral head. Passively apply a slight posterior force to the humeral head, pull tape over top of shoulder, and anchor medial to the inferior scapular border.

- Repeat as needed, beginning each strip of tape overlapping the previous one.

Scapular Stabilization Taping Instructions

Several variations of taping to stabilize the scapula and normalize scapulohumeral rhythm are described in the literature.6,7,10,12,15,20,24,25 Similar taping variations are also described as an attempt to inhibit the upper trapezius muscle and/or maximize activation of the lower trapezius muscle.7,8,15,26 The taping method for scapular stabilization described by Cools et al6 and Morrisey7 is presented in Figure 8–3.

Figure 8–1 Taping procedure for multidirectional instability.

- Begin tape over anterior shoulder, just below the coracoid process.

- Pull superiorly and then posteriorly on the tape to anchor over the lower thoracic area.

Acromioclavicular Joint Taping Instructions

Various taping methods to stabilize the AC joint after an injury have been described in the literature.15,19,20,27 The method pictured in Figure 8–4 was found to be effective at decreasing pain and contributed to range of motion (ROM) and strength improvements in a published case report.19

- The patient’s elbow should be supported and an approximation force applied to the shoulder joint to move the humerus superiorly.

- Begin the first strip of tape over the middle deltoid and pull upward to anchor tape proximal to the AC joint. Tape should not interfere with the upper trapezius muscle belly.

- The second strip of tape is applied from the coracoid process to the spine of the scapula.

Figure 8–3 Taping procedure for scapular stabilization.

Figure 8–4 Taping procedure for the acromioclavicular joint.

Effectiveness of Shoulder Taping in Orthopaedic Conditions

Although shoulder taping is frequently used as an adjunct to treat and prevent shoulder injuries, its effectiveness has not been well studied in the published literature. Case studies that have been found present anecdotal evidence for the use of shoulder taping in the treatment of a variety of shoulder pathologies, including impingement,10–12 AC joint sprains,19 shoulder subluxation secondary to neurologic disorders,18 and chronic shoulder dislocations exacerbating symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy.17 In all of these case studies, tape was used as an adjunct to other methods of conservative treatment, including modalities, postural education, and rotator cuff and scapular muscle strengthening. The authors noted symptom relief and improved shoulder function and attributed these outcomes to the tape application. However, the use of multiple interventions in most studies makes it difficult to attribute the results to shoulder taping alone.

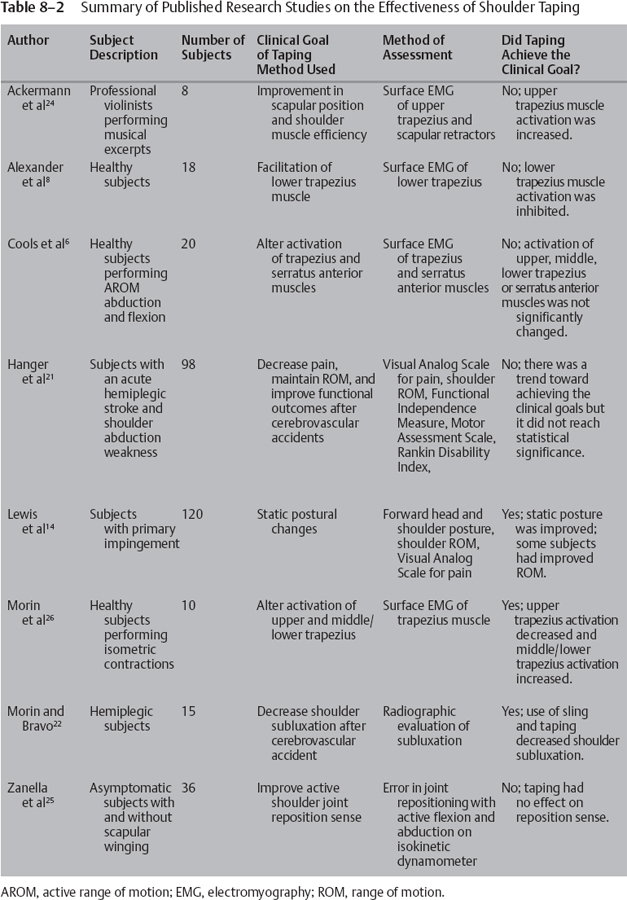

Despite the positive outcomes with taping presented in these case studies, there is no consensus on the effect of shoulder taping in research studies. It is difficult to summarize and compare the current literature because of the use of various taping methods and outcome measures. Research on the effects of shoulder taping on scapular muscle activity, GH joint proprioception, impingement, and joint laxity secondary to neurologic disorders is discussed below. The results are summarized in Table 8–2.

Orthopaedic Applications

Three published research studies have investigated the effects of shoulder taping on ST muscle activity in healthy shoulders. The two most comparable research studies were done by Morin et al26 and Cools et al6 to determine the effectiveness of tape on inhibiting the upper trapezius muscles. In both studies, tape was applied by starting on the anterior shoulder, pulling firmly over the upper trapezius, and attaching the tape medial to the scapula at a lower thoracic level. Morin et al26 found taping did inhibit the upper trapezius muscle and increased middle/lower trapezius muscle activity during isometric contractions. In contrast to these beneficial effects, Cools et al6 found taping had no significant effect on the electromyographic (EMG) activity of the trapezius (upper, middle, and lower) or serratus anterior muscles during dynamic movements. Although EMG results are less steady during dynamic movements than isometric contractions, dynamic movements are more functional and clinically relevant.6

Ackermann et al24 investigated the effect of tape on muscle activity in string musicians during functional activity. Tape applied as described by Morrisey7 to increase scapular retraction and upward rotation was found to have no effect on scapular rotator muscle activity and actually increased upper trapezius activity. In addition, taping had the negative effects of decreasing comfort, concentration, and performance quality as reported by the violinists. The authors suggest more positive results may occur if tape was repeatedly applied so subjects could become accustomed to the tape. Also, repeated tape application may allow for adaptation of neural pathways.

Some of the strongest anecdotal evidence for shoulder taping is based on its presumed ability to stimulate cutaneous receptors and improve proprioceptive and kinesthetic awareness. Research on this hypothesis includes two studies investigating the effect of shoulder taping on joint reposition sense. Zanella et al25 found scapular taping had no effect on shoulder joint reposition sense. This was true for shoulders with and without scapular winging. Hiltbrand et al9 investigated the effects of McConnell taping on joint-reposition sense in shoulders with and without multidirectional GH joint laxity. Results showed an increase in accuracy of joint position sense by 1.449 degrees in flexion and 1.221 degrees in abduction when the tape was applied. Although this increase in joint-position sense was statistically significant, the clinical significance of a goniometric measurement of <2 degrees was questioned by the authors.

Research by Lewis et al14 and Page and Stewart13 investigated the effect of shoulder taping in subjects with primary and secondary impingement, respectively. Lewis et al14 examined the effects of changing posture on shoulder ROM in subjects with and without primary subacromial impingement. Changes in shoulder pain were also evaluated in the symptomatic subjects. Tape was applied over the thoracic spine in an attempt to create a postural change. With the scapula in a position of retraction and depression and the thoracic spine extended, tape was placed from T1 to T12 and from the spine of the scapula to T12. Results showed taping did produce favorable static postural changes including decreased forward head posture, forward shoulder posture, and thoracic kyphosis in both symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects. This study does not give any evidence that posture during movement was altered by the taping technique. Taping allowed greater ROM before the onset of pain in symptomatic subjects; however, the intensity of pain when it did occur was not reduced. The authors suggested future studies investigate the long-term effects of taping and the characteristics of subjects who will benefit from taping because not every subject responded favorably.

Page and Stewart13 investigated the effects of taping on secondary impingement. Subjects included were recreational athletes with laxity of the GH joint capsule and positive impingement testing. The authors found that shoulder taping, in addition to rotator cuff strengthening, scapular stabilization exercises, and posture education was effective in decreasing pain and improving function in subjects with secondary impingement. Subjects were seen for 7 to 20 visits and returned to athletic activity after 2 to 8 weeks of treatment. No other specific data was included in this abstract.

Mulligan23 (unpublished data) has also researched the use of tape to optimize shoulder position and possibly improve shoulder function. Subjects in this study were high school baseball pitchers with and without scapular muscle weakness. Isokinetic strength and pitch velocity were tested in all subjects with and without a taping technique to place the humerus in a posterior position. Results showed improvement in external rotation (ER) to internal rotation (IR) strength ratios and pitch velocity in subjects with and without scapular weakness when the taping procedure was applied. Subjects with scapular weakness had an increase in pitch velocity from 65.72 miles per hour to 67.24 miles per hour after tape was applied. Pitch velocity increased from 69.88 to 71.44 after tape was applied in subjects without scapular weakness. There were no significant improvements in strength or pitch velocity in either group with a placebo taping procedure; hence, the author hypothesizes the improvements seen are because the tape had a stabilizing effect on the ST articulation and optimized the biomechanics of the shoulder complex.

Neurologic Applications

In addition to its use in treating orthopedic conditions, shoulder taping has been shown to be effective in reducing subluxation secondary to neurologic disorders. The combination of shoulder taping and use of a sling had a greater effect on reducing subluxation in hemiplegic shoulders than either intervention separately.22 Although not statistically significant, Hanger et al21 found a trend toward decreased pain, preservation of ROM, and improved functional outcomes in hemiplegic patients with shoulder abduction weakness that underwent shoulder taping.

Shoulder Braces

Shoulder Braces

Use of Shoulder Braces in Return to Athletic Activity

Although not as commonly prescribed as knee and ankle braces, shoulder braces are used during sports participation. Braces are used pro-phylactically in returning athletes to sport with the goal of increasing GH joint stability. By limiting abduction and ER, a brace could potentially prevent anterior glenohumeral dislocations, which account for the majority of recurrent dislocations. Factors related to a brace’s ability to limit ROM include the restraint system (i.e., laces, plastic clips), deformation of composition materials, and brace–body interface.28 Similar to shoulder taping, braces have not only mechanical but also proprioceptive effects to minimize joint injury.

Examples of Shoulder Braces Used during Athletic Activity

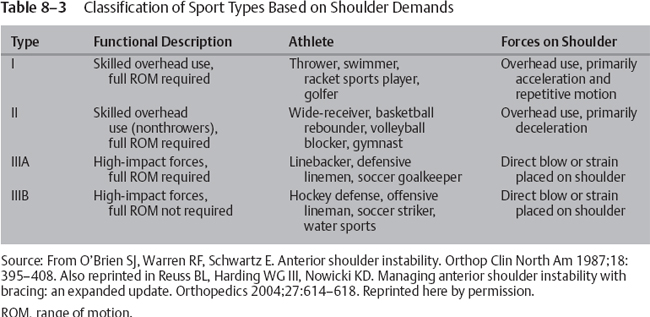

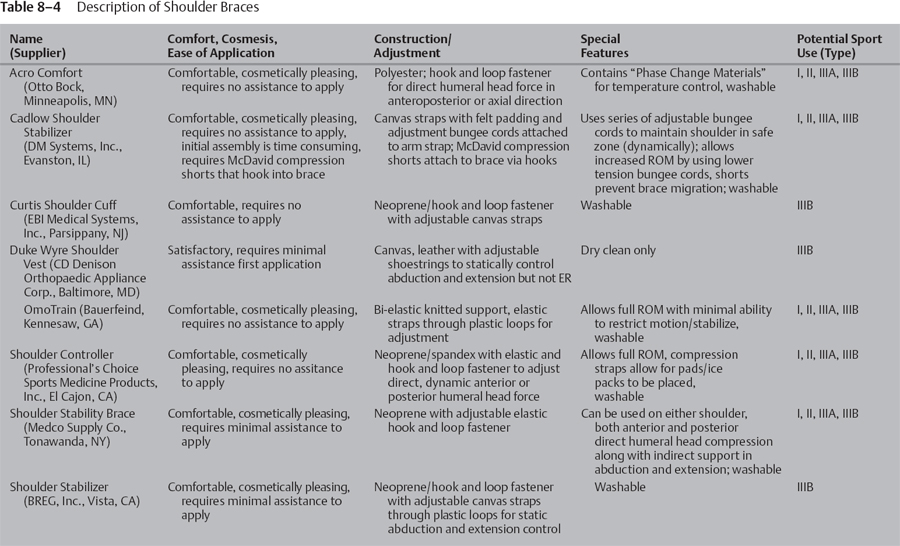

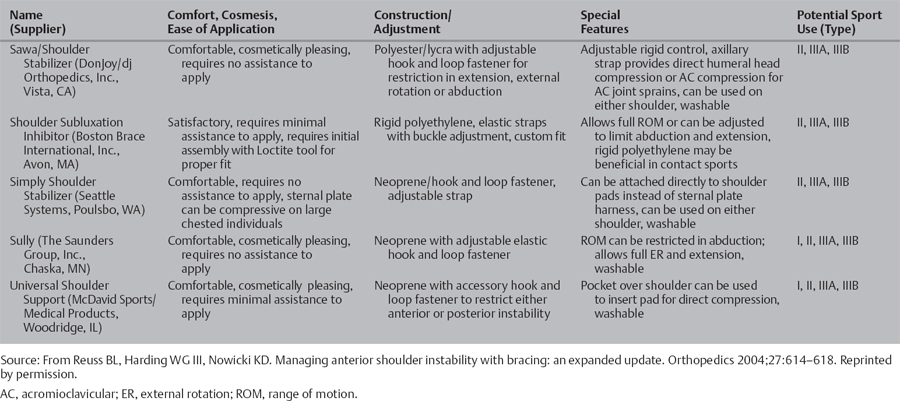

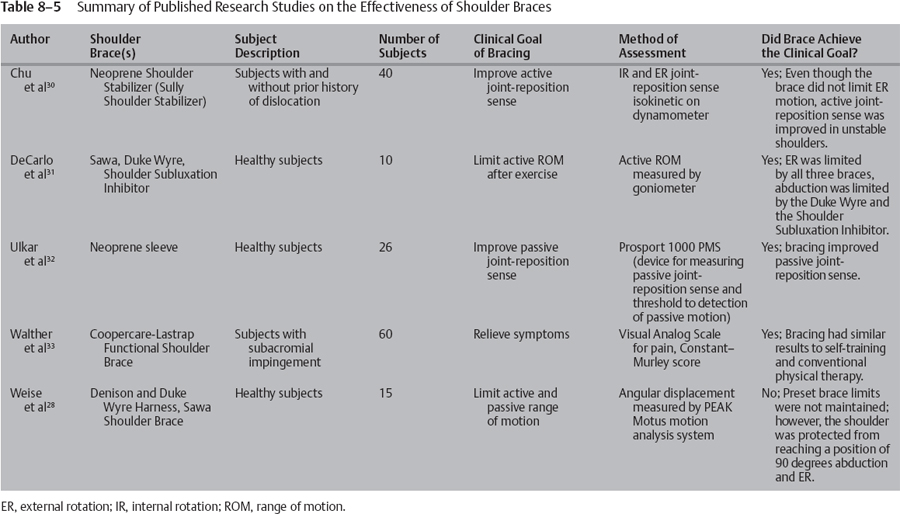

Braces vary in design characteristics and capability to limit different motions; therefore, the individual athlete and sport need to be considered to determine the most appropriate brace. A thorough review of functional shoulder braces for athletes with anterior shoulder instability was published by Reuss et al.29 The authors provide a classification system of sports based on shoulder demands (see Table 8–3). Thirteen shoulder braces are described, including supplier, comfort, cosmesis, ease of application, and special features (refer to Tables 8-4 and 8-5).29 Examples of three shoulder braces commonly used for athletes with shoulder instability are shown in Figures 8-5 to 8-7. In addition to bracing for instability, a scapula winger’s brace has been described in the management of long thoracic nerve palsy.34

Evidence-Based Effectiveness of Shoulder Braces

Current research on the effectiveness of shoulder braces has investigated injury recurrence rates, motion restriction, and joint reposition sense. Clinical observations by Sawa35 report no injury recurrence after GH subluxation or dislocation in hockey players following a three-phase rehabilitation program. The three phases included: (1) rest and nutrition, (2) interferential current and muscle stimulation, and (3) a traditional progressive-resistance weight-training program in conjunction with a shoulder orthosis. The author feels these three phases help optimize the natural healing process after injury. The orthosis used permitted variable restriction of shoulder abduction, allowing controlled movement within safe ranges of motion. The above clinical observations suggest use of a shoulder orthosis during the healing process to optimize shoulder rehabilitation and decrease injury recurrence rates. Sawa35 reports further scientific research is needed to determine the specific role of the orthosis in the healing process.

Two published research studies have investigated the effect of braces on limiting shoulder passive and/or active ROM. DeCarlo et al31 studied the effects of three shoulder braces, Sawa (DonJoy/dj Orthopedics, Inc., Vista, CA), Duke Wyre (CD Denison Orthopaedic Appliance Corp., Baltimore, MD), and Shoulder Subluxation Inhibitor (Boston Brace International, Inc., Avon, MA), on limiting active motion following isokinetic exercise. All three braces did exhibit a loosening effect and allowed a significant increase in flexion ROM after exercise. However, a significant increase in ER was not allowed by any of the braces. The Duke Wyre and Shoulder Subluxation Inhibitor braces were also effective in limiting abduction. Because it allows flexion ROM and limits abduction, the authors suggest the Shoulder Subluxation Inhibitor brace may be useful for sporting activities that require overhead movements.

Weise et al28 found similar effects when investigating the Duke Wyre and Sawa shoulder braces. Although neither brace maintained its preset limit of 45 degrees abduction during active or passive joint movement, both braces effectively prohibited the shoulder from actively reaching the vulnerable position of 90 degrees abduction and 90 degrees ER where dislocations are likely to occur. These two braces also limited passive abduction to <90 degrees and the Sawa brace limited passive ER to <90 degrees. Passive ROM is important to consider because passive forces can cause injury during contact sports. Published abstracts agree with the findings of the above studies that shoulder braces loosen with shoulder movement and do not restrict active ROM to preset limits.36,37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree