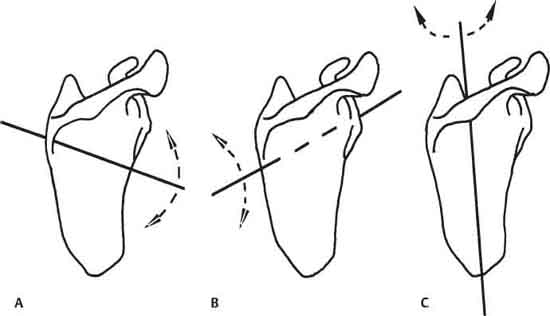

6 W. Ben Kibler Scapular dyskinesis can be evaluated on physical exam; its treatment may be one of the keys to the treatment and rehabilitation of shoulder injury. In this chapter, normal SHR in shoulder function and abnormal rhythm in shoulder injury are reviewed, and guidelines are provided for shoulder evaluation and treatment. Many studies have evaluated scapular and arm motion and have reported on the coupled motions. These reports studied two-dimensional (2D) motion of arm elevation and scapular upward rotation.1,2 They showed a composite humerus to scapular (H:S) ratio of 2:1, although the H:S ratio varied widely within segments of the arc of motion. Recent work has examined scapular motion in a three-dimensional (3D) context. These studies have shown that scapular motion is a composite of three motions: (1) upward-downward rotation around a horizontal axis perpendicular to the plane of the scapula (Fig. 6–1A), (2) anterior-posterior tilt around a horizontal axis in the plane of the scapula (Fig. 6–1B), and (3) internal (IR) and external rotation (ER) around a vertical axis through the plane of the scapula (Fig. 6–1C).3,4 There are two translations with an intact acromioclavicular (AC) joint:upward and downward translation on the thoracic wall and retraction-protraction around the ellipsoid curve of the rib cage. In this more complex framework, the scapula is shown to have several roles in shoulder function. In addition to upward rotation, the scapula must also posteriorly tilt and externally rotate to clear the acromion from the moving arm.3–5 Also, the scapula must internally and externally rotate and posteriorly tilt to maintain the glenoid as a congruent socket for the moving arm and maximize concavity and compression.6 Finally, the scapula must be stabilized in a position of relative retraction during arm use to maximize activation of all the muscles that originate on the scapula.7 Figure 6–1 The three motions that comprise normal scapular kinematics. (A) Upward-downward rotation around a horizontal axis perpendicular to the plane of the scapula. (B) Anterior-posterior tilt around a horizontal axis through the plane of the scapula. (C) External–internal rotation around a vertical axis through the plane of the scapula. These positions and motions are produced and maintained by coordinated patterns of muscle activation that are preprogrammed and task specific.1,8,9 They create force couples to stabilize and move the scapula and move the arm.8,10,11 A predominant force couple pattern involves upper trapezius and serratus anterior activation to initiate scapular upward and ER, followed by lower trapezius activation to stabilize the rotated scapula and add additional posterior tilt as the arm is maximally elevated.8 These activations precede maximal rotator cuff activation, allowing the cuff to contract off a stabilized base.11 Another important force couple includes middle trapezius: serratus anterior working as external rotators of the scapula. Finally, the lower trapezius is coupled with the latissimus dorsi to rotate the elevated arm on the stabilized scapula. Scapular dyskinesis is found in a high percentage of patients with shoulder injuries.4,5,10,12 Biomechanical studies reveal that the dyskinesis is a combination of decreased posterior tilt and decreased ER as well as decreased upward rotation.4,5 Clinical studies on dyskinesis have been difficult because of the inability to “see” the scapula because of the multiple possible positions and the muscular covering. The predominant finding on clinical exam is a prominence of the medial border of the scapula upon observation at rest or upon motion of the arm in elevation. This finding has been broken down into the most common patterns that are observed. The most common patterns include inferior border prominence (type I), entire medial border prominence (type II), or superior medial border prominence (type III) (Fig. 6–2).13 These patterns are consistent with the three possible motions in 3D space. The patterns may occur singly in one patient, but they commonly occur in combinations of patterns as the arms move. They are not specifically associated with any particular shoulder injuries, but types I and II are more commonly seen with instabilities and labral injuries, and types I and III are more commonly associated with rotator cuff injuries. These patterns represent loss of dynamic control of the translation of scapular retraction and the motion of ER. Scapular retraction is regarded as a key element in closed chain coupled SHR.1,3,4 If this control is lost, gravity, forward arm motion, and muscle activations take the arm and shoulder girdle forward. The biomechanical result is a tendency toward scapular IR and protraction around the rib cage. Excessive scapular protraction alters the scapular roles in shoulder function.14 The normal timing and magnitude of acromial motion are changed, the subacromial space distance is altered, the GH arm angle may be increased, producing the “hyperangulated” joint, and maximal muscle activation may be decreased. These patterns appear to be independent from the various diagnoses of shoulder injury, such as AC joint arthrosis, GH internal derangement or instability, biceps tendinopathy, or labral injury. They appear to be the result of abnormal muscle activations, either directly due to muscle involvement or to neurologically based inhibition, or alteration in muscle activation patterns from a wide variety of causative factors. Causative factors for scapular dyskinesis may be broadly classified into proximal (to the scapula) and distal types.15 Proximal causative factors are most frequently because of direct alteration of muscle properties, such as inflexibility, weakness, fatigue, or nerve injury, and are usually treated by rehabilitation. Muscle weakness has been demonstrated in the serratus anterior5,16 and lower trapezius5 in impingement patients. This has been shown to be due to fatigue and inhibition of activation.16 Occasionally, it will be the result of a direct injury due to trauma. Alteration in muscle activation patterns, with delayed upper trapezius activation, has also been demonstrated.10 Inflexibility in the pectoralis minor is a common finding in impingement. This has been shown to be an absolute decrease in muscle length and an increased muscle activation in response to tensile loads.17 A relatively rare proximal cause is true nerve injury to the long thoracic or accessory nerve. Bony proximal causes include thoracic kyphosis or scoliosis, with resultant alteration in scapular position. A surgically treatable proximal cause is lower or middle trapezius muscle detachment off the medial border, either due to trauma or because of surgical treatment of snapping scapula syndrome. Traumatic detachment is rare but has been seen after tensile stretch over a seat belt in vehicular accidents or after direct blows. If a patient has the same or worse symptoms after snapping scapula surgery, the muscles may not be properly attached. Figure 6–2 Patterns of scapular dyskinesis. (A) Inferior medial border prominence. (B) Medial border prominence. (C) Superior medial border prominence. Distal causative factors are most commonly due to anatomic injuries in the AC or GH joints. They also alter muscle activation patterns or activations by causing instability of the bones or through pain-based inhibition, but frequently require surgical treatment to eliminate their effects and provide the basis for effective rehabilitation. GH instability is associated with altered serratus anterior activation18; GH instability and rotator cuff injury are associated with altered SHR that improves after surgical treatment.19 Superior glenoid labral tears are associated with dyskinesis in 94% of the cases.20 A common distal causative factor that rarely needs surgical treatment is glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD). GIRD is defined as side-to-side asymmetry of >25 degrees or an absolute value of <25 degrees.20 It is thought to be produced by acquired posterior capsular contracture and posterior muscle stiffness and is frequently seen in all types of shoulder injuries.20,21 GIRD creates abnormal scapular kinematics because of the “wind up” effect of the arm on the scapula. As the arm is forward flexed, horizontally adducted, and internally rotated in throwing or working, the tight capsule and muscles pull the scapula into a protracted, internally rotated and anteriorly tilted position, which causes downward rotation of the acromion (Fig. 6–3).

Classification and Treatment

of Scapular Pathology

Scapulohumeral Rhythm in Shoulder Function

Scapulohumeral Rhythm in Shoulder Function

Scapular Dysfunction in Shoulder Injury

Scapular Dysfunction in Shoulder Injury

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree