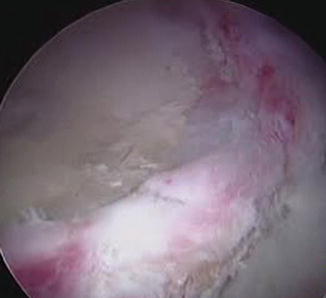

Fig. 1

Arthroscopic view of a deficient labrum in a hip that has undergone previous labral debridements (Courtesy Steadman Philippon Research Institute)

Labral Function

The acetabular labrum attaches to the outer rim of the acetabulum and plays an important role in the normal mechanical function of the hip joint [7, 8]. The intact labrum deepens the socket which limits femoral head translation. In addition, the labrum provides a fluid seal to maintain the hydrostatic fluid pressure within the joint [9, 10]. This fluid seal protects the cartilage with the diffusion of nutrients to chondrocytes and also reduces cartilage consolidation by helping to distribute forces throughout the joint [11]. Labral dysfunction can lead to overloading of the articular cartilage of the hip and may be a precursor of osteoarthritis [12].

Etiology

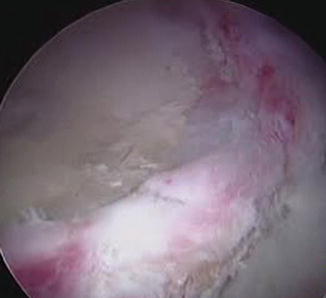

While labral tears are associated with damage caused by femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), labral deficiency has multiple etiologies. This can be seen in primary or revision arthroscopies. Labral tears can be complex in nature, with complete disruption of the longitudinal fibers (Fig. 2). These tears are often seen in traumatic hip dislocations The labrum no longer functions and there is not enough healthy tissue to repair. As with the meniscus of the knee, labral tissue needs to be preserved for the health of the joint. Removing the complex tear would result in a deficient labrum. In addition, hypotrophic labrums are also seen in hips with no prior surgeries. In this chapter, a deficient labrum is defined as one that is 3 mm or less in width (Fig. 3). In primary arthroscopies, a hypotrophic labrum can be an anatomic variation or from repeated damage due to impingement.

Fig. 2

Arthroscopic view of a labrum with a complex tear with complete disruption of longitudinal fibers (Courtesy Steadman Philippon Research Institute)

Fig. 3

Deficient labrum as seen at arthroscopy (Courtesy Steadman Philippon Research Institute)

Labral deficiency has multiple etiologies in the revision arthroscopy case including debridement, arthrofibrosis, and complex tears [1, 2, 13, 14]. After the pathophysiology of femoral acetabular impingement was popularized by Ganz and others, the most popular treatment to manage the resultant labral injuries was labral debridement and resection [2]. However, multiple studies have shown higher reoperation rates and lower modified Harris Hip Scores with labral debridement versus labral repair [3, 5, 6].

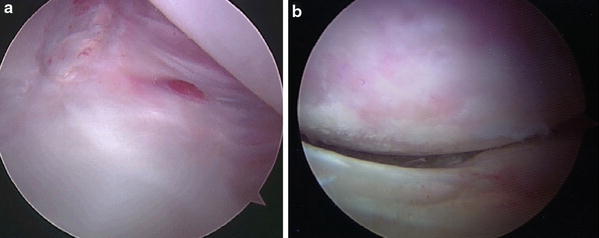

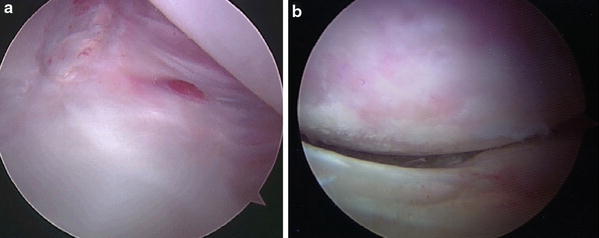

Arthrofibrosis can frequently form after injury or as a sequel of hip surgery [12, 13]. Adhesions are commonly seen in the hip at the site of the femoral neck osteoplasty and between the labrum and capsule (Fig. 4a, b). Occasionally the hip capsule can adhere to the labrum effectively elevating the labrum and disrupting the contact between the labrum and femoral head. This results in an area of deficiency in the biomechanics of the labrum. Despite careful separation of these adhesions, the remaining tissue is either of insufficient volume or has poor quality thereby creating a labral deficiency.

Fig. 4

(a) Adhesions between the capsule and the labrum seen during revision arthroscopy (Courtesy Steadman Philippon Research Institute). (b) Adhesions causing the labrum not to seal with the femoral head (Courtesy Steadman Philippon Research Institute)

Hip Stability/Labral Deficiency

Sporting activities which require repetitive twisting and pivoting of the hip put athletes at risk for labral tears and hip instability . The labrum is a secondary stabilizer of the hip and increases the articular contact area and volume of the acetabulum by 22 % and 33 %, respectively [8]. Ferguson et al. showed that after labral debridement the force to dislocate the hip is reduced [9]. Crawford et al. demonstrated that loss of the labrum leads to decreased femoral stability relative to the acetabulum during extremes of range of motion. In particular, 60 % less force is required to distract the femur 3 mm after the labrum has been removed [17]. Benali et al. reported gross instability resulting in hip subluxation after debridement of the acetabular labrum [13]. Meyers, et al. showed that while sectioning of iliofemoral ligament alone resulted in increased translation and external rotation, if the labrum was also sectioned, these values significantly increased [18]. If the iliofemoral ligament and the labrum were repaired, the translation and external rotation significantly decreased [18].

When the labrum is deficient, the amount of strain on the remaining labrum also puts the hip at risk for instability. Smith and Sekiya also have demonstrated that labral strain increases as the circumferential tear is enlarged particularly after 2 cm of deficiency is obtained [19]. Frequently these patients will have pain and sensations of the hip slipping during extremes of motion.

Ferguson and Ganz also demonstrated that after labral, resection fluid pressurization in the central compartment was markedly lowered and cartilage consolidation was greater, in the labral deficient group than the intact group [18]. A recent study has shown that a fluid efflux was increased in hips with a labral tear compared to those with an intact labrum and that the efflux specifically occurred at the tear location [20]. Labral debridement was also associated with a higher fluid efflux compared to normal hips [20].

Dysplasia

The deficient labrum is even a greater problem in a patient with shallower hips. Henak et al. showed that the labrum has an even more critical role in dysplastic hips as it has a significant role in load transfer and hip stability than in hips with normal acetabular geometry [21]. The study showed in a normal model the labrum supports 1–2 % of the load, while in a dysplastic model, the labrum supports 4–11 % of the load. In the dysplastic model, the femoral head was in equilibrium at the lateral edge of the acetabulum instead of centered in the acetabulum. In addition, the study showed that cartilage contact area was lower in the dysplastic model during walking and going up and down stairs. The study concluded that the labrum may play a larger role in joint stability in the dysplastic hip. This reinforces the need for treatment of labral deficiency in the dysplastic hip [21]. In symptomatic dysplasia, labral tears have been seen in up to 90 % of cases [22]. Therefore, most authors recommend treatment of labral tears with repair primarily or in the setting of a deficient labrum to consider labral reconstruction in the dysplastic hip. Furthermore labral reconstruction and repair also plays a critical role in patients requiring bony correction of their dysplasia. The timing of when to perform labral repair and reconstruction in the context of a patient needing a bony correction surgery is still debated.

Cartilage Effects of Labral Deficiency

The acetabular labrum provides the suction seal to the central compartment. The function of this seal is to aid in the fluid dynamics of the hip joint [10, 11]. Through the seal, distraction and shear forces are reduced as described by Ferguson et al. [10, 11]. In addition cartilage consolidation is much greater in a labral deficient hip. Many authors have demonstrated that tears and partial resection of the labrum can dramatically reduce the functional seal. Furthermore others have shown a resultant increase in cartilage load, concentration, and potentially shear forces, predisposing the articulation to early degenerative changes after a labral tear or labral resection [11, 20]. Song has also demonstrated that the resistance to rotation is increased once the acetabular labral seal is lost such as in the setting of focal or complete labral resection [23]. Greaves et al. measured articular cartilage strain in cadaveric hips under a compressive load using 7 T MRI. The author found no significant effect of a labral tear compared to the intact state but did find a 4–6 % decrease in cartilage strain associated with labral repair compared to labral resection [24, 25]. Thus the labrum plays a vital role in the preservation of the labral seal of the central compartment and has potential cartilage protective effects by reducing cartilage strain and shear forces.

Treatment Alternatives

Non-operative Management

If a patient has minimal pain with his or her current activity level, non-operative treatment is an alternative. Furthermore if the patient demonstrates findings consistent with osteoarthritis and/or a joint space less than 2 mm, then management should consist of conservative management with injections until they are a candidate for arthroplasty [5, 6, 26].

Reconstruction

Several authors have described methods to reconstruct the labrum [1, 27–29]. Tissue such as the iliotibial band (allograft and allograft), gracilis, and ligamentum teres have all been described to reconstruct the labrum [1, 27–29]. The goals of reconstruction are to maintain the acetabular seal to improve the fluid mechanics in the central compartment and reduce shear forces on the acetabular cartilage [1, 20, 27–29]. The senior author uses iliotibial band autograft tissue (Fig. 5) in most cases; however, in cases of very large labral deficiencies, an allograft is used.