1

Introduction to Medical Conditions

At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following:

1. Discuss the basic differences between orthopedic and general medical assessment

2. Appreciate the athletic trainer as a health care provider in the recognition, referral, and disposition of medical conditions

3. Use proper communication as a valuable tool in the general medical assessment of the physically active person

4. Apply principles of disease transmission prevention

5. Implement and use the regulations and laws that govern care and privacy of patients

6. Apply CPT and ICD codes to medical conditions

7. Explain the purpose of the preparticipation examination (PPE) for athletes, and identify the medical organizations that provide guidelines

8. Differentiate between the office visit and station-based PPE

The Role of the Athletic Trainer in General Medical Concerns

Although this text is not exclusively for certified athletic trainers, he or she is often the person who has the first opportunity to identify a medical issue for an athlete. A brief understanding of education and training of certified athletic trainers is warranted for the reader to appreciate their role with the physically active patient (Box 1-1). An athlete who is feeling ill commonly turns to the athletic trainer because the athletic trainer is the most accessible health care provider. The athletic trainer working with a team has established a rapport with the athletes and is familiar with their previous medical history and normal performance. This may allow the athletic trainer to detect a condition that otherwise might go unnoticed. The athletic trainer working with college or professional teams is also responsible for the health care of the entire team while on the road. Although many medical problems are orthopedic, the conditions an athletic trainer encounters also can include infections, colds, and other maladies, which need to be identified and properly treated in order for the athlete to continue to participate in sports at optimal levels.

In 1999 the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) first identified a new series of educational competencies and clinical proficiencies that focused on several areas not previously part of the athletic trainers’ educational process1: pathology of injury and illness, pharmacology, and general medical conditions and disabilities. These competencies and proficiencies have become part of athletic training educational curricula throughout the country and have been expanded in subsequent professional requirements.2

The athletic trainer has also taken on a greater role in the general health care of the physically active, thereby requiring greater emphasis on the clinical evaluation and diagnosis of general medical problems. This is a result, in part, of advances in medical science that enable athletes with medical conditions, who would formerly have been excluded from participation, to compete at the highest levels. It also is the result of expanding employment opportunities for athletic trainers. Athletic trainers are now employed in corporations, industries, inpatient hospitals, outpatient clinics, and other nontraditional workplaces as well as the traditional realms of interscholastic, intercollegiate, and professional sports.3,4 Athletic trainers also serve as physician extenders in many states and see a more diverse population, including the pediatric athlete (Figure 1-1), physically active mature and older adults, as well as those with physical impairments.5

Learning more about medical conditions and their assessment is therefore a part of the comprehensive educational process of the athletic trainer. A recent study on the continuing educational needs of athletic trainers revealed that staying abreast of the latest techniques and continuing the learning process throughout their careers were some of the most important reasons cited for completing continuing education.6 The athletic trainers included in this study expressed a desire to obtain information about general medical conditions more frequently than other orthopedic conditions because those conditions had been well covered previously in the athletic training curricula.6

Communication

The health care provider can also facilitate and encourage communication by slightly leaning toward the patient, maintaining eye contact, having an open posture, repeating key words the athlete uses, and using simple phrases for encouragement, such as “go on” or “mm-hmmm.”7 Being empathetic—for example, “that sounds difficult”—and allowing pauses that give the athlete time to add to comments reassure the patient that the clinician is listening carefully (Figure 1-2). Asking about the patient’s feelings associated with symptoms is also appropriate in medical assessment. Last, a good practitioner can summarize and interpret the athlete’s comments by saying, “I hear you say…” rather than empathetically injecting words or opinions into the conversation during the subjective review of symptoms.7

Communication with Health Professionals

Because some of these communications may be in written notes, athletic trainers need to understand standard abbreviations as well. Appendix A lists many common abbreviations that relate to medical care. Table 1-1 lists terminology used to describe medical conditions and situations that are used throughout this text.

TABLE 1-1

| Term | Definition |

| Adventitious | Coming from an external source; occurring spontaneously |

| Afebrile | Without a fever; also apyretic |

| Biopsy | Removal and examination of tissue |

| Comorbid | Two or more possibly unrelated medical conditions existing at the same time |

| Constitutional | Relating to the body as a whole |

| Erythema | Redness of the skin brought about by capillary dilation |

| Febrile | Having a fever |

| Malaise | A general feeling of discomfort or uneasiness; often the first symptom of an illness or infection |

| Morbidity | Consequences of a given illness |

| Mortality | Death from a particular illness or disease |

| Palliative or supportive | Reducing the severity of an illness or treatment of disease without curing it |

| Prodromal | Preillness symptoms |

| Purulent | Pus filled |

| Sequela, sequelae | A condition occurring as a consequence of a given illness or disease |

| Suppurative | Pus forming |

Prevention of Disease Transmission

Everyone who works in the health care field appreciates the need to prevent disease transmission. Protection from infection and maintaining a sanitary environment are two critical elements in caring for patients with illnesses. Another prevention technique is immunization from specific diseases by vaccine. Chapter 15 discusses vaccination as well as established standards for preventing the spread of disease and illnesses.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is an organization that sets standards to protect health care workers and their patients. OSHA standards apply only to established relationships between employers and employees and do not extend federal protections to students.8 However, students who could potentially be exposed to hazardous waste in facilities where they practice or observe should follow the safety standards set forth by OSHA, receive training, and have ready access to precautionary materials, such as barriers and proper disposal containers.

OSHA has a right to inspect any facility under its auspices without prior notification, and it has the power to suspend or shut down a facility, as well as impose hefty fines for noncompliance with standards.9,10 The most familiar OSHA requirement affecting athletic medical care concerns the blood-borne pathogen (BBP) standard. Athletic trainers must be intimately familiar with this standard because many athletes are at risk of open wounds in the course of their activities and subsequently have potential for the transmission of infection.

OSHA Standards for Blood-borne Pathogens

The BBP standard is intended to safeguard health care workers against hazards resulting from exposure to infectious body fluids and covers anyone who could reasonably anticipate having occupational exposure to infectious waste (e.g., blood). Included in this standard is a description of how to formulate an individualized institutional or setting exposure control plan. A written document outlines steps to take and specific people to call in the event of an exposure to infectious waste. An exposure may range from a needle stick to having blood spilled onto intact skin. All health care workers must have an operating knowledge of their employer’s plan, access to personal protective equipment, BBP training, and knowledge about who to contact should an exposure occur.11

The BBP standard uses the phrase “universal precautions” to emphasize that all human waste should be treated as if it were infectious and that health care workers and patients must be protected in every situation in which they might be exposed to body fluid, including contact with mucous membranes in the eyes, mouth, or nose; genital secretions; or blood. Any sharp object that may be contaminated with infectious waste, such as needles, scalpels, or broken glass, is also considered potentially hazardous material.11 Box 1-2 has suggestions for handling infectious waste.

Barriers to Blood-borne Pathogens

Barriers are devices worn to protect both the health care worker and patient against the spread of disease. The traditionally accepted barrier is latex gloves, but OSHA also requires access to face and eye protection, gowns, and mouthpieces for resuscitation.11,12 Health care workers with allergies to latex must be provided with an alternative material suitable as a barrier against transmission of BBPs.

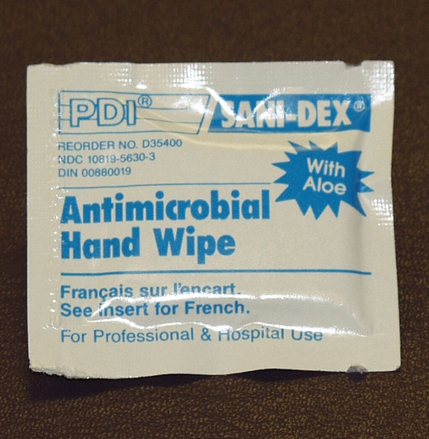

All health care workers must have ready access to barriers that fit properly in order to retard infection from hazardous materials. Ideally, soap and water are the best methods to clean hands before and after glove use (Box 1-3). If soap and water are not readily available, commercial disinfectant gels or single-use wipes can sanitize hands (Figure 1-3).

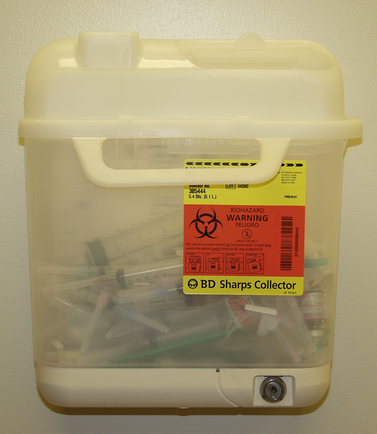

Sharps containers are specially built units that have one-way valves (Figure 1-4) and are used to accommodate sharp instruments such as needles and scalpels that may have infectious materials on them. These containers should never be opened or overstuffed. Intercollegiate sports medicine guidelines require that all necessary materials, such as barriers, bleach, waste receptacles, and wound coverings, comply with universal precautions and be available to all health care providers.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree