Introduction

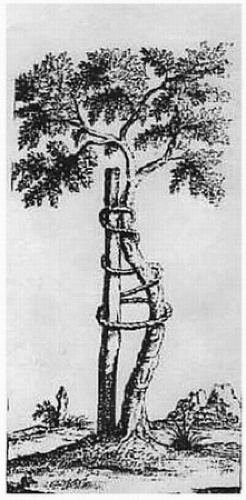

Orthopædic derives from L’Orthopedie (1741) by Nicholas Andry de Bois-Regard (1658-1742). It is derived from Greek ορθºζ: “straight” and παιζ (root παιδ—): “child.” Andry was a Professor of Theology before becoming a Professor of Physick in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris. The remainder of the title explains his purpose: “Or, the art of correcting and preventing deformities in children: by such means, as may easily be put in practice by parents themselves, and all such as are employed in educating children.” The book emphasized simple remedies even a child’s caretaker could administer, such as straightening by bracing [A]. Nowhere is surgery mentioned.

GROWTH

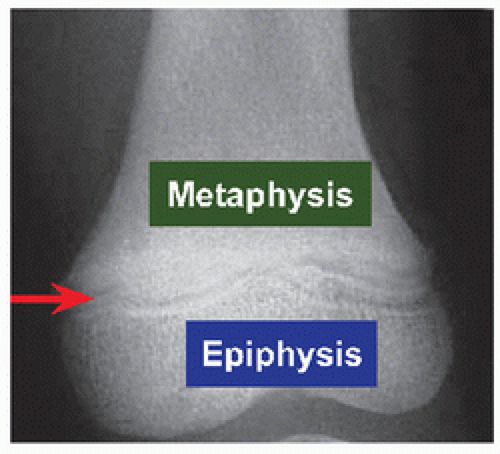

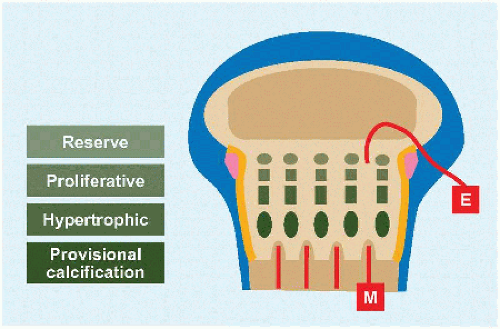

Growth distinguishes the child [B].

Joint

Joints may be fibrous, for example, syndesmosis and symphysis, or synovial, in which the skeletal elements are in contact but not in continuity: they are draped by hyaline cartilage of which the purpose is motion and not structure. Innervation of synovial joints is of two types.

Myelinated group A fibers in the capsule detect joint position and motion.

Unmyelinated group C fibers in blood vessels of the synovial membrane transmit pain. Joint injury or disease results in effusion, which stretches these fibers and hurts. The child accommodates by placing the joint in the position that maximizes volume and thereby reduces pressure, for example, flexion, lateral rotation, and abduction in an infected hip.

In children, a third type of articulation occurs, synchondrosis, during coalescence of ossification centers or bony segmentation: persistence may cause dysfunction, for example, tarsal coalition.

Joints develop first as a cleft in mesenchyme, which chondrifies and cavitates by the end of 3rd month. The process is regulated by the HOX family of genes. Joint development requires motion; hence, joint dysplasia in neuromuscular conditions characterized by akinesia or dyskinesia, such as arthrogryposis.

Bone

Timing of ossification influences care of the child. Imaging of hip dysplasia is facilitated by appearance of the proximal epiphysis of the femur, absent at birth. Patellar ossification after the 2nd year may delay diagnosis of its disorders. The multiple secondary ossification centers of the elbow appearing at different ages obfuscate the unfamiliar.

A Tree. The enduring symbol from an engraving on the frontispiece of L’Orthopedie. A straight stake is tied to a crooked sapling to partially correct it and guide its growth. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Intramembranous ossification Mesenchymal stem cells give rise to osteoblasts that secrete osteoid that mineralizes directly without an intervening cartilage model. In achondroplasia, this process is spared.

Relatively normal size of clavicles results in broad shoulders; of fibulæ, it results in ankle varus; of skull, it results in a large head.

Disordered endochondral ossification is seen as a “champagne pelvis,” resulting from constriction at the triradiate cartilage amidst flat bones produced by intramembranous ossification.

Constriction of the midface with unfettered surrounding osseous growth disrupts breathing.

Constriction of the foramen magnum compresses the brainstem.

Intramembranous ossification also is the mechanism responsible for periosteal appositional growth (bone width) and fracture healing.

Endochondral ossification During the 6th week of gestation, mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into chondrocytes to form a model of the future skeleton. During the next week, periosteum forms, and by the 8th week, vascularization is under way [C]. Vascularization ushers in ossification and the fetal period. Secondary ossification of the epiphysis begins after birth, with the exception of the distal femur, which is present at birth. In between the primary and secondary ossification centers is interposed the physis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree