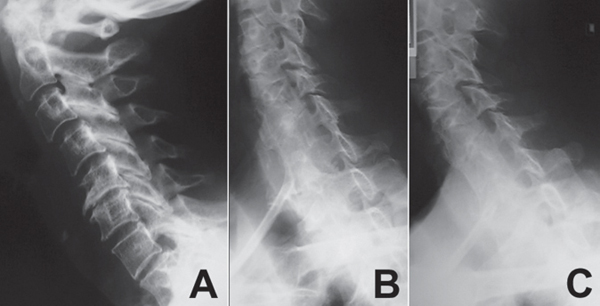

65 Of the advances that have been made in recent years in spine care, none is more significant than the advances in spinal imaging. Modern imaging studies improve the diagnostic capability of the spine surgeon and allow a more targeted approach to spinal pathology. Imaging studies reviewed in conjunction with the history and physical examination play a role in establishing the diagnosis of many spinal conditions. Although there is no specific classification for spinal imaging, the following tests are discussed: plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scanning, CT myelography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and bone scans. The workup of a patient with spinal complaints must begin with a thorough history and physical examination. Only then can a differential diagnosis for the patient’s problem be considered and a rationale for workup be suggested. Imaging studies are an important part of that workup. However, imaging studies should never be used as the sole means for diagnosing spinal conditions, as most modern imaging modalities have the potential to reveal pathology that is not symptomatic or pertinent to the patient’s complaints. Plain radiographs are generally the first study to be ordered for most patients. They are less expensive than MRI or CT and provide information on the spinal alignment, degenerative changes, and bone quality (Fig. 65.1A–C). They are helpful in excluding fractures, deformities, and destructive bony lesions. They can also show soft-tissue shadows that are helpful in some cases. Dynamic flexion-extension views are helpful in ruling out instability of the spinal segments. Plain radiographs are relatively insensitive for early infection or metastasis and do not show soft-tissue pathology, such as a disk herniation. MRI has become the advanced imaging modality of choice for most spinal conditions requiring more than plain radiographs. MRI provides excellent detail of the hard and soft tissue and demonstrates the spinal canal, neural elements, ligaments, disks, and paravertebral tissues in addition to the skeletal structures (Fig. 65.2). MRI can be used to define early infections and metastasis and may demonstrate occult fractures of the vertebral body. In the postoperative setting, MRI is helpful in defining many sources of pain, including infection and retained pathology, although the early (first 3 months) MRI studies done following surgery may be difficult to interpret accurately because of postoperative edema. In this setting, MRI is often performed with gadolinium to help delineate between scar, infection, and retained disk material. MRI has limited value for defining a fracture in cortical bone (posterior element fracture) and is contraindicated in patients with pacemakers, certain metallic implants (cochlear implants), metallic fragments in the eyes, and/or aneurysm clips. MRI may demonstrate significant artifact when used around large metallic implants, particularly if the implants are made from metals other than titanium alloy. Fig. 65.1 Lateral plain radiograph (A) shows degenerative changes at the level of the cervical spine. The oblique views (B,C) help in assessing spondylosis at the neural foramen levels.

Imaging for Back Pain and Spinal Infection

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

Spinal Imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree