Chapter 9 How to interface auricular diagnosis with clinical status

THE VALIDATION OF AURICULAR DIAGNOSIS

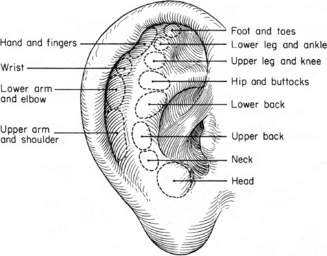

The term auricular diagnosis was first proposed officially by Terry Oleson in 1980.1 His study, conducted at the department of anesthesiology at the UCLA School of Medicine in Los Angeles, belongs to the history of ear acupuncture. Its aim was to evaluate the claims by French and Chinese acupuncturists that a somatotopic mapping of the body is represented upon the external ear. Forty patients were examined by a physician to determine which of 12 reported areas of their body suffered musculoskeletal pain (Fig. 9.1). Each patient was then covered with a sheet to conceal any visible physical problems. A second physician afterwards carried out a blind examination of the patient’s auricles for areas of higher tenderness or reduced electrical skin resistance. The ear points corresponding to body areas where the subject reported musculoskeletal pain were designated as ‘reactive points’, while ‘non-reactive points’ corresponded to areas of the body where the patient experienced no discomfort.

The results of Oleson’s study were as follows:

The interesting conclusions of the article by Oleson and colleagues were that:

this study also indicated that the auricular diagnosis technique is often sensitive to pathological problems of which the patient is only minimally aware. When some patients were told of their auricular diagnosis results, they suddenly remembered having a minor or old pain problem in that bodily area, a problem which they had neglected to mention during the medical evaluation. Since these post-hoc results were derived after the ear diagnosis had been made, these instances were not included in any statistical analyses. Nonetheless, such observations do suggest that auricular diagnosis may be effectively employed as part of a general medical evaluation designed to reveal all organic aspects of a patient’s pain complaint. Since there are also ear points for abdominal and thoracic bodily organs, auricular diagnosis could also be utilized with standard diagnostic procedures for analyzing pathological conditions related to internal pain or referred pain.1

Since then Oleson’s research has become the major reference study and has been cited in several articles on ear acupuncture. A recent paper, however, re-examined the question of whether auricular maps were reliable for chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders.2 Fortunately the authors had no intention of replicating Oleson’s study but only of proposing a different method for validating auricular diagnosis by using a 250 g algometer. The main shortcomings of this study were the limited number of patients examined (only 25), the lack of importance given to the posterior surface of the ear, which was not examined at all, and the adoption of an arbitrary somatotopic arrangement of the auricular zones which does not faithfully correspond either to the French or to the Chinese map. For example the knee was reproduced twice on two different areas roughly representing it, according to the schools just mentioned. It is not reported in the article which of the two the blind assessor had to consider as corresponding to a painful knee, or whether both corresponded. In contrast, in Oleson’s study the 12 different auricular regions chosen for the research were the faithful somatotopic representation of the body according to the Chinese map.

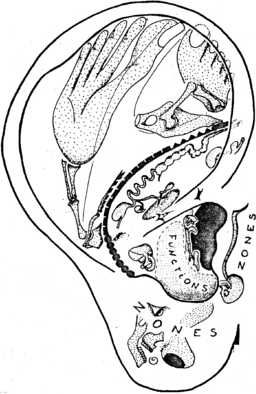

Bourdiol in particular introduced the concept of somatotopic area early, but the most interesting interpretation of the body’s representation on the auricle is probably that of Jean Bossy,3 former director at the Montpellier Institute of Anatomy and author of several books and articles on the neurophysiological basis of acupuncture. His representation of the homunculus on the auricle4 is probably more realistic and useful for the practitioner than the well proportioned fetus which we see on the common drawings of the ear. As in the homunculus sensitivus and motorius of Penfield, the hand and the thumb have a large representation as well as the lips, the nose and the jaws (Fig. 9.2).

A NEW PROJECT FOR VALIDATING AURICULAR DIAGNOSIS

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

The higher number of female patients attending my clinic is not unusual for therapists practicing complementary techniques. Several factors could explain this phenomenon: in my opinion it could be related to what today seems to be a stronger desire in females compared to males to preserve their health at its best, or perhaps to the search for alternative treatments to drugs with pronounced side-effects or which are feared to be potentially harmful.

Another characteristic in the patient population I examined was the relatively high percentage aged >60 years (22.3%). This factor is possibly due to the greater presence of musculoskeletal disorders in this phase of life. Indeed, if we consider the 5641 symptoms reported the most numerous are those related to the musculoskeletal system (32.7%), followed by psychological/psychiatric symptoms (22.5%). Table 9.1 lists further symptoms related to other organs and systems in decreasing order of frequency.

Table 9.1 Classification and percentage of 5641 symptoms declared/identified in 506 patients

| Symptom | % |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | 32.7% |

| Psychological/psychiatric | 22.5% |

| Gastrointestinal | 14.7% |

| Cardiovascular | 6.8% |

| Nervous system (central/peripheral) | 4.6% |

| Dermatological | 4.6% |

| Genitourinary | 3.7% |

| Ear, nose and throat | 2.9% |

| Endocrine and metabolic | 2.7% |

| Teeth and temporomandibular joint | 2.3% |

| Other | 2.5% |

| Total | 100% |

RESULTS

The aim of my validation was to find answers to the following questions:

Were the different diagnostic methods quantitatively equivalent in unveiling the patient’s problems?

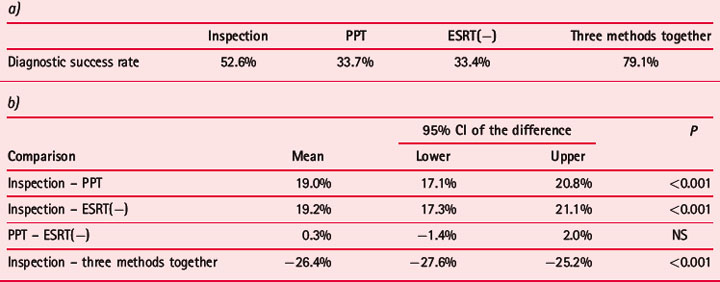

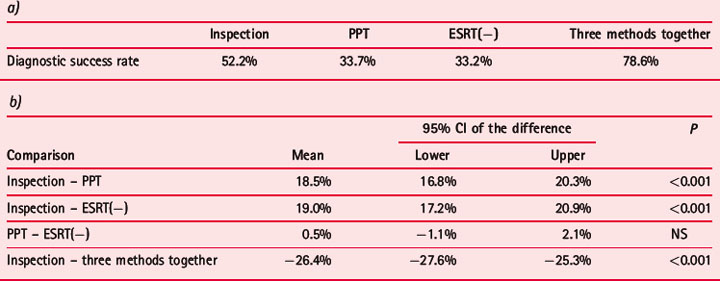

The three diagnostic methods used had different success rates for the identification of patients’ symptoms. First came inspection with 52.2%, followed by PPT with 33.7% and ESRT(−) with 33.2%. Interestingly, if a symptom had been identified by at least one method there was a success rate of 78.6% (Table 9.2a). The significance of this is evident: the experienced practitioner, who generally applies all the proposed methods, acquires a better understanding of patients’ conditions. This result is confirmed by the significantly higher diagnostic potentiality of the three methods together compared to the inspection alone (Table 9.2b).

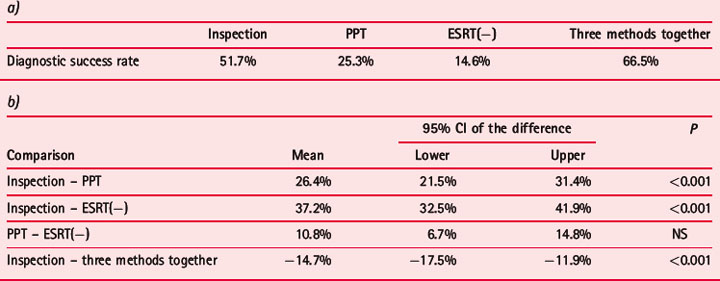

Table 9.2 Diagnostic success rates (%) obtained in the identification of 5641 symptoms in 506 patients with three methods: inspection, PPT and ESRT(−) (a); comparison of the different methods with paired samples t-test (b)a)

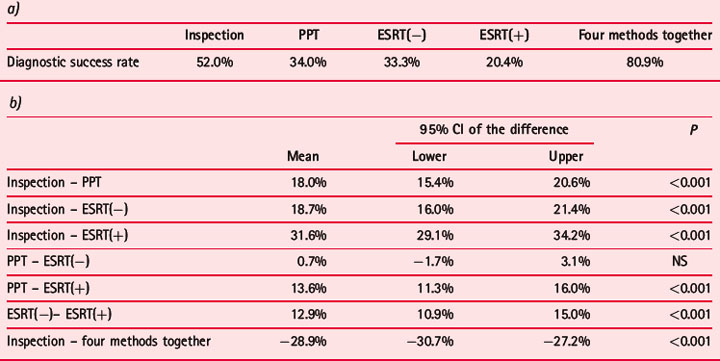

As expounded in Appendix 2, the Agiscop device used in the diagnostic procedures reported in this book allows a double electrical test, choosing either the minus (–) or the plus (+) modality. In 202 patients out of the total group of 506 we added the + modality, even though the average number of identified points is usually lower than with the − modality and consequently appears to identify a lower number of disorders in the patient. The success rates according to the four methods employed were as follows: (i) inspection 52%; (ii) PPT 34%; (iii) ESRT(−) 33.3%; (iv) ESRT(+) 20.4%. Thus, as expected, the + modality showed a lower success rate than the − modality; nevertheless its application as a fourth diagnostic modality increased the total success rate to 80.9% (Table 9.3).

Were the different methods equivalent in diagnosing recent and past problems?

The success rates in identifying these two categories of symptoms were very similar for all three diagnostic methods. It has to be stressed that the group of recent disorders scored only 11.2% of the total; this is a further sign that my population of patients asking for help from acupuncture was composed of people suffering especially with chronic recurrent ailments. I was somewhat surprised by the results for inspection, which I expected would have a much higher importance in diagnosing older problems. Nevertheless, inspection showed a better diagnostic success rate in both cases compared to PPT and ESRT. The latter, however, showed no significant difference either for recent or old problems (Tables 9.4 and 9.5).

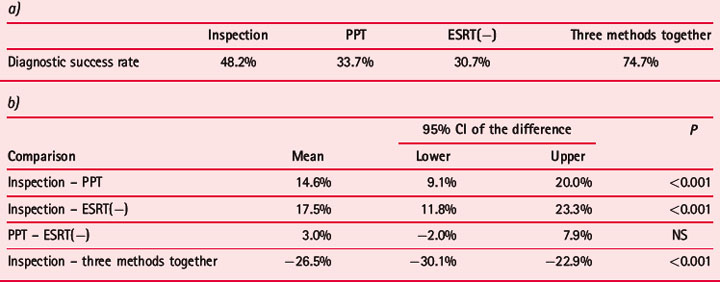

Table 9.4 Diagnostic success rates (%) obtained in the identification of 570 symptoms, occurring in the prior 6 months, with three methods: inspection, PPT and ESRT(−) (a); comparison of the different methods with paired samples t-test (b)a)

In the case of musculoskeletal disorders, were the different methods equally effective in detecting the prevalent side of pain?

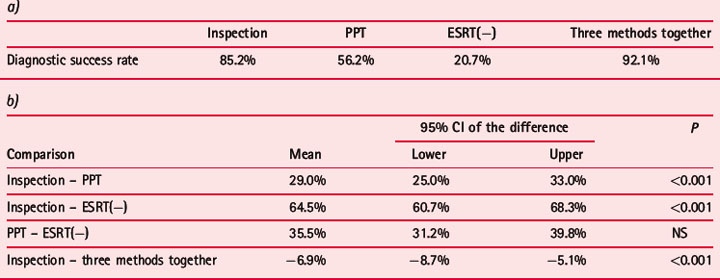

In my blind examination of the patient I had three options for determining the prevalent side of pain: right, left and bilateral. In diagnosing musculoskeletal pain disorders I obtained the following success rates for ipsilateral (right- or left-sided) pain: (i) inspection 51.7%; (ii) PPT 25.3%; (iii) ESRT (−) 14.6% (Table 9.6). If the pain was bilateral or without prevalence for one side, the success rates were, as expected, higher: (i) inspection 85.2%; (ii) PPT 56.2%; (iii) ESRT (−) 20.7% (Table 9.7). These results show that it is easier to identify a bilateral pain disorder on the auricle, especially with inspection and PPT.

Table 9.7 Diagnostic success rates (%) obtained in the identification of 755 bilateral musculoskeletal pain disorders with three methods: inspection, PPT and ESRT(−) (a); comparison of the different methods with paired samples t-test (b)a)

CONCLUSIONS

The conclusions of my validation can be summarized as follows:

a large number of various and repeated observations could not permit me to state a priori that a certain auricular zone could be active on the ipsilateral or contralateral side of the body. A series of thorough investigations indeed allowed me to ascertain that the same region could act either on one side or the other. By means of all researches I have done, I am now convinced that the confounding factor was due to an interaction between the symmetrical points of the two auricles. When we are going to stimulate point A on the right ear we stimulate at the same time point A′ on the left ear. This explains the crossed action of the auricular points: even if the stimulated point originally corresponds to the ipsilateral side of the body, the active point is in this case located symmetrically on the opposite ear.5

AURICULAR POINTS/AREAS INTERFACING WITH A PATIENT’S CLINICAL CONDITION

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree