Chapter 4 Inspection of the outer ear

INTRODUCTION

So far, in Western countries, inspection of the outer ear has attracted little attention with the exception of the ear lobe, the diagonal crease of which has been thoroughly studied in patients with cardiovascular risk (see section entitled ‘The diagonal ear lobe crease or Frank’s sign’ later in this chapter).

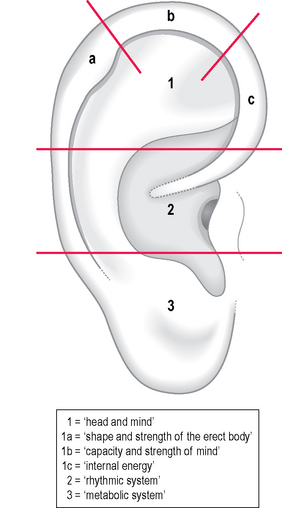

The physician Norbert Glas1 proposed a physiognomic classification of the outer ear into three parts (Fig. 4.1):

The French author was aware that certain skin alterations of the auricle could be found on the corresponding area of a suffering organ. He said: ‘When the patient is affected by a longstanding disease, we can recognize its signature on the ear.’

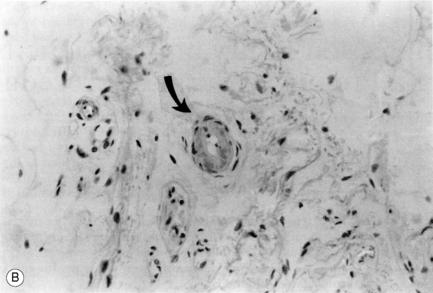

He referred two clinical cases with skin alterations of the lung area.2 The first was a patient with severe non-responding eczema of the buttocks, genitals and face. Furthermore Nogier identified a small area of eczema corresponding to the lung; this led him to suspect a tubercular origin for the eczema which afterwards responded well to the appropriate treatment. The second case was that of a patient who had been affected for several years by pneumothorax; the corresponding lung area was well recognizable on inspection because it was creased and yellowish.

The French lung area corresponds on the whole to the Chinese one (CO14 Fei); nevertheless, in the latter the lung has a larger representation, occupying almost the whole inferior concha. The dimensions of this area are proportional to the importance of the lung in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM); the indications for treatment are cough, chest congestion and hoarseness, but also skin disorders such as acne, itching and urticaria. Other indications are constipation and control of the abstinence syndrome as described in Chapter 1.

THE CHINESE CONTRIBUTION TO THE INSPECTION OF THE OUTER EAR

As noted in Chapter 1, the application of the principles of TCM to ear acupuncture by Chinese therapists favored an original development of this discipline. If we consider the four different diagnostic methods proposed by TCM, besides pulse and tongue diagnosis, we find examination of the patient at the top, followed by the interview, auscultation and smelling and palpation of the body. It is not by chance that palpation has been ranked last; an aphorism written by the famous physician Pien Chueh in his book Nan Jing (Difficult Classic) was:

Nevertheless, observations on the auricle were scanty compared to those on the tongue and the other parts of the face. Among signs found in Chinese classical textbooks are those related, for example, to the color of the helix3 (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Some explanations of abnormal color of the helix according to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (after Maciocia3)

| Color of the helix | Tone | Energetic explanation according to TCM |

|---|---|---|

| Pale | Bright | Yang deficiency |

| Pale | Dull | Blood deficiency |

| Pale | Deep and ‘thick’ | Qi deficiency with Phlegm |

| Yellow | Bright | Damp-Heat; Heat predominates |

| Yellow | Dull | Damp-Heat; Dampness predominates |

| Greenish | Blood stasis from Heat | |

| Greenish | Dark | Kidney-Yin deficiency |

| Bluish | Blood stasis from Cold | |

| Red | Heat in the Lung and/or in the Heart | |

| Red | Floating | Kidney-Yin deficiency with Empty-Heat |

The auricular inspection proposed by Chinese acupuncturists after 1958 goes beyond a simple somatotopic diagnosis as conceived in Western countries: it reflects the concept of the human body according to the rules of TCM. The body is a united totality of contradictions. Every single part of it is closely physiologically interconnected. After the onset of disease, a local ailment reflects itself on other parts as well as on the whole, while the transformation of the whole will certainly exert an influence locally. This is the reason why Chinese acupuncturists proposed a points selection for the ear according to the pien-cheng sih chih method, where pien-cheng means grasping the essence of a disease by distinguishing the subjective and objective symptoms, and sih chih means treating diseases according to the principles of TCM after analyzing and synthesizing a patient’s symptoms. In this way, for example, the heart and small intestine are correlated, and therefore a cardiovascular pathology will evoke a positive reaction on the ear’s area for the small intestine.4

It is possible, in my opinion, that auricular inspection as proposed by Chinese acupuncturists has not been considered essential in the West because of the almost complete lack of photographic documentation. The historical textbook of the Nanjing military headquarters was the only one in the early 1970s that contained a few color plates related to diseases of the uterus, stomach and liver. A fourth plate showed desquamation of the lung area in a case of skin disease. Nanjing’s test, which has been translated into several languages, among them English5 and Italian,6 reports type and location of the various skin alterations observed in the different diseases. Unfortunately the description of ‘positive reaction points,’ as they were called by the army doctors of the Nanjing garrison, does not follow any dermatological classification and we cannot understand, for example, what ‘congestive papules’ or ‘white small spots with reddish borders’ are. The authors, however, examined about 20 000 patients by simple inspection, reaching the conclusion that when certain internal organs or local areas of the human body suffer through illness, especially organic diseases, positive reactions will appear on the corresponding regions or specific areas of the majority of the patients. These pathological changes are symbolized by changes in skin color, deformation, desquamation and papules, etc.

The general instructions recommended by the authors for correct auricular inspection are as follows:

Points 2 and 5 are important for making a reliable inspection; as regards point 4, it is rare in our countries to find scars from chilblains. Tenderness at pressure of a skin alteration is, however, fundamental for diagnosis and may be used to treat symptoms. For example, acupuncture on a sensitive telangiectasia located within the representative area of a painful joint sometimes gives very quick and lasting relief.

CLASSIFICATION OF SKIN ALTERATIONS OF THE OUTER EAR

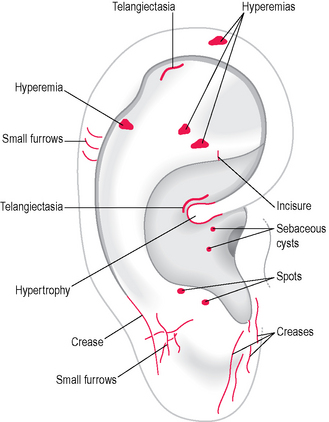

One of the major difficulties in ear inspection is how to classify the auricle’s skin alterations. Chinese authors limited the auricular reactions to four categories (change in color, deformation, papules and desquamation) whereas Nguyen proposed nine different categories distinguishing the following elements:7

I did not feel satisfied with this classification and here propose an alternative which in my opinion includes all of the auricle’s visible elementary skin lesions. In my research I was helped by a dermatologist, Antonia Pata, and together we set up a classification which includes six groups of alterations related to the vascularization, pigmentation, keratinization, cartilaginous, cutaneous and sebaceous gland structure of the auricle (Table 4.2).

Table 4.2 Classification of skin alterations (SAs) of the outer ear according to Pata and Romoli

| Category | Type of SA | Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| SA related to vascularization | – reticular telangiectasia | |

| – punctiform telangiectasia | ||

| – linear telangiectasia | ||

| – spider angioma | ||

| – punctiform angioma | ||

| SA related to pigmentation | – isolated spot | |

| – pigmented area | ||

| – mixed melanin–hemosiderin area (grey, yellow, orange) | ||

| – blue | ||

| – melanocytic | ||

| SA related to keratinization | – furfuraceous scales | |

| – psoriasiform scales | ||

| SA related to cartilaginous structure | ||

| SA related to cutaneous structure | ||

| SA related to sebaceous gland structure |

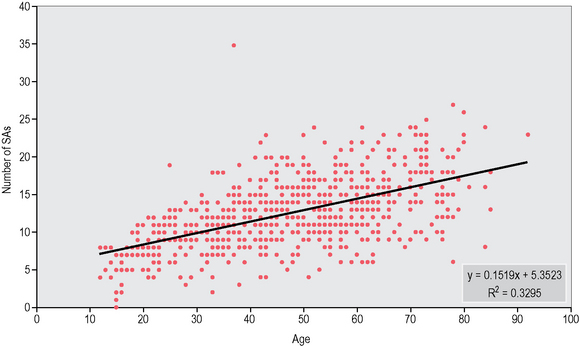

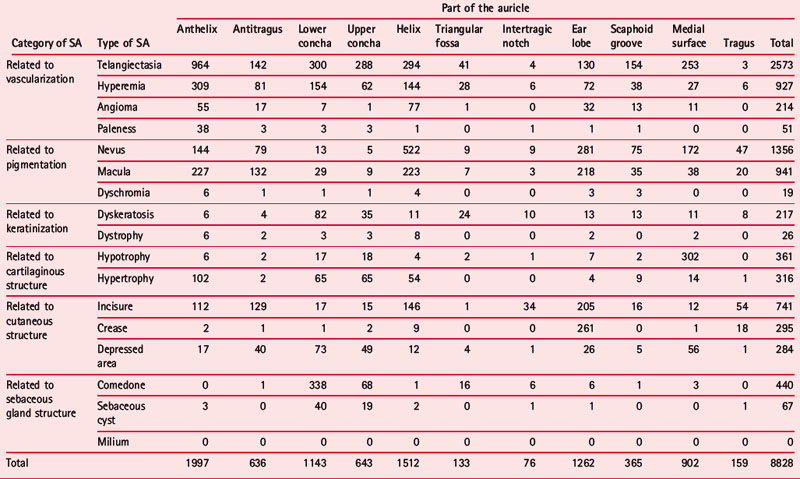

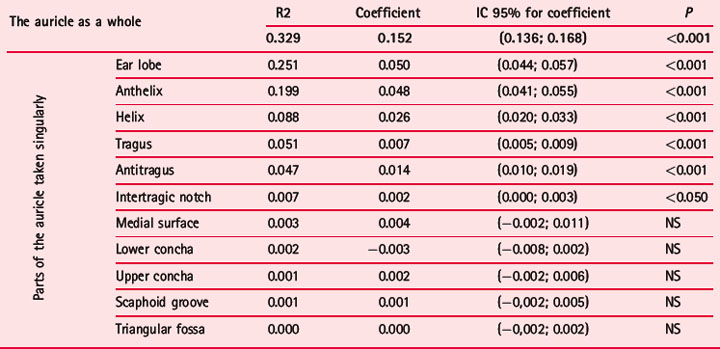

Using this classification I examined 711 patients of various ages (471 females, average age 46.9 years, range 12–92, SD 17.4; 240 males, average age 45.6 years, range 12–85, SD 18.4). I photographed both ears of every patient and reported on the Sectogram those skin alterations which I could detect with my naked eye. A database was created with the following data from every patient: age, sex, symptom prompting request for help, current or past important diseases, surgical operations, traumas, location and type of skin alterations. The main aim in assembling these data was to establish if ear inspection offers any elements of specificity which could be used in the process of auricular diagnosis. The total number of skin alterations was 8828 with an average of 12.4 skin alterations per patient, range 0–35, SD 4.7; the distribution on the right and left was almost equal; 52.7% on the right and 47.3% on the left auricle. The higher rate of skin alterations was found on the anthelix followed by the helix, the ear lobe and the cymba concha. A decreasing rate was found on the cavum concha and the medial surface of the ear; on the remaining parts (tragus, triangular fossa, intertragic notch) the rate did not reach 5% of the total (Table 4.3). The total number of skin alterations varies with the age of the patient and in both sexes there is a progressive increase passing from younger subjects to patients aged 70 or over (Fig. 4.2). The outer ear therefore acts as a mirror reflecting not only diseases of single organs but also the whole ageing process of a patient’s body. This process is not homogeneous on all auricular parts; indeed some of them, such as the ear lobe, anthelix, helix, tragus, antitragus and intertragic notch, show a significant correlation between age and the number of skin alterations (Table 4.4).

Table 4.3 Distribution of skin alterations (SAs) (summing those of the right and left ear) on the different parts of the auricle in 711 patients

Table 4.4 Correlation in 711 patients between age and the number of skin alterations on the auricle as a whole and on its different parts

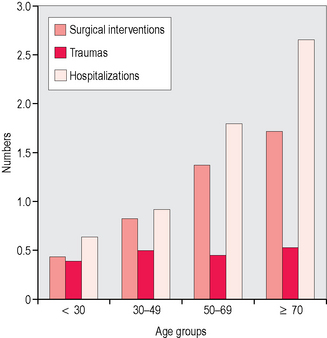

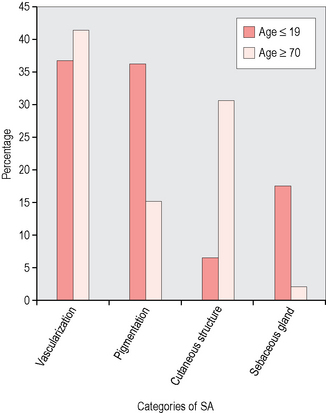

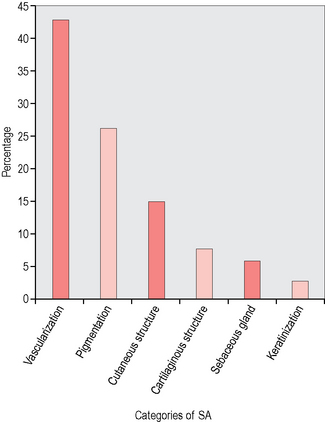

Another parameter which varies with age and accompanies the increasing number of skin alterations is the number of hospitalizations and, to a lesser extent, the number of surgical operations, whereas the number of traumas remains constant throughout the decades examined (Fig. 4.3). The skin alterations are not evenly distributed through the six different categories: vascular skin alterations (particularly telangiectasia and hyperemia) correspond to 42.6% of the total followed by pigmented skin alterations (mainly nevi and maculae) corresponding to 26.2%; skin alterations of skin structure (creases and incisures) correspond to 15%. The remaining three groups follow with percentages below 5–10% (Fig. 4.4). The six categories of skin alteration have a different distribution on the 11 areas of the auricle. Telangiectasia are mostly seen on the anthelix, nevi prevalently on the helix followed by the ear lobe. Maculae have a uniform distribution on the anthelix, helix and lobe. The skin alterations of sebaceous gland structure (particularly comedones) were found mainly on the cymba conchae followed by the cavum conchae. Also depressions and dyskeratosis were found mostly on the cavum conchae. Also interesting is the comparison between the different percentage distribution throughout the six categories in the extremes of the age groups: younger people tended to have pigmented skin alterations (especially nevi) followed by vascular and sebaceous gland skin alterations (comedones), whereas in the oldest group of patients vascular skin alterations ranked first, followed by creases, incisures and pigmented skin alterations (especially maculae) (Fig. 4.5). The scantiness of skin alterations on the medial surface compared to those on the lateral surface is remarkable and only 902 (10.2% of the total) were found there. It is possible that this percentage could be higher if inspection of the medial surface were easier, if we consider that pain pressure test (PPT) tender points of this area in 325 patients were 14.4% and those with lower electrical resistance 19% of the total.

Fig. 4.4 Percentage distribution of skin alterations (SAs) in each of the six categories in 711 patients.

As an example of auricular inspection and correct methodology in recording skin alterations, I here report the case of an elderly woman. Considering type of skin alterations and above all their location, I could confirm the presence of some past and current health problems. In this case the difference between the richness of skin alterations on the lateral surface and their scantiness on the medial surface is clearly outlined.

The patient was a 77-year-old woman, 162 cm tall and weighing 65 kg (who in the past had weighed up to 83 kg). She had undergone the following surgical operations: appendectomy at the age of 19, uterine retroversion at age 27, crural hernia at 45, uterine–bladder prolapse at 60. She had suffered from depression when she was young and after menopause. She reported having suffered from chronic migraine for at least 50 years and even after menopause. She still suffered occasionally from attacks, mainly on the right side. She had had hypertension for at least 30 years, controlled by drugs. Some members of her family (brother, sister and nephew) had hypertriglyceridemia. Her levels of triglycerides had often been above average, reaching a maximum of 600 mg.

Inspection of the lateral surface of the right ear showed a series of skin alterations which can be described as follows (Fig. 4.6):

METHODOLOGY OF INSPECTION

As recommended by the Chinese, good lighting is important and my advice is to adopt either natural light or white light, possibly employing the type of magnifying lens used by dermatologists. In photography a ring-flash easily evidences more hidden areas and gives very good images. The flash may provoke reflex vasodilatation causing a significant change in the skin alterations, especially those of vascular type. Such vasodilatation may occur particularly when touching, lifting or bending the auricle, for example during examination of the posterior part of the auricle. It is therefore advisable first of all to fully inspect the lateral part of the auricle and then the medial part, keeping the hair away. Every skin alteration must be transcribed on the Sectogram according to type and topography before taking pictures, touching the ear or applying any other subsequent diagnostic method such as the pressure pain test or electrical detection.

As regards the topography of skin alterations, a reliable diagnostic clue becomes available if the area in which the skin alteration is located overlaps with the accepted representation of the corresponding anatomical part. In some cases, unfortunately, the expected correspondence is not found and incomplete overlapping of these areas may be misleading. This is the case, for example, of neighboring structures such as those pertaining to the lower and upper limbs. In the case of Plate IIIA, the telangiectasia appeared to overlap with the Chinese representation of the knee, but instead the patient had had a carpal syndrome for several months. We should by no means feel disappointed, but try with our medical knowledge to verify diagnosis through clinical judgment and the help of diagnostic instruments, imaging techniques and laboratory tests available in our profession.

DOES INSPECTION HAVE THE SAME VALUE IN ALL SECTORS OF THE OUTER EAR?

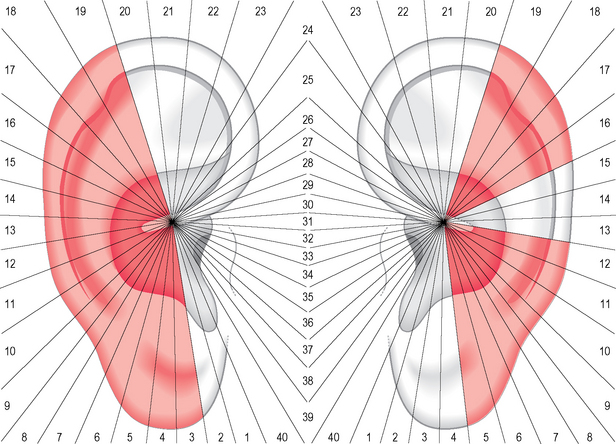

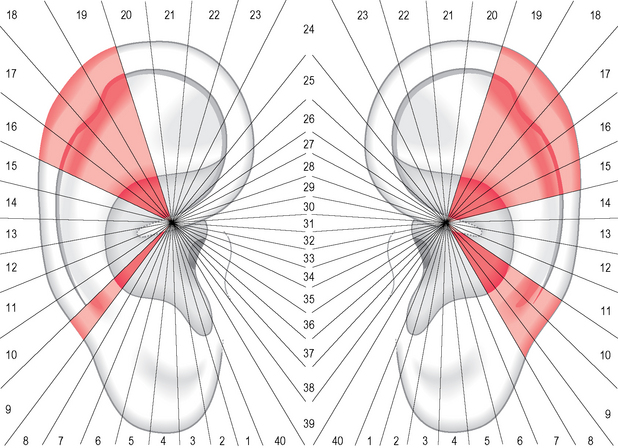

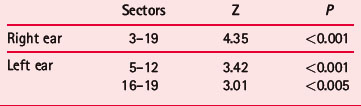

If we consider the mean number of skin alterations on the right and left ear we obtain respectively 7.5 and 6.7. We would therefore expect a uniform distribution among the different sectors but this is not always the case. If we make a spatial cluster analysis8,9 of the total number of skin alterations on the right and left ears, regardless of sex, we may observe that there are some specific sectors with a significantly higher concentration. Figure 4.7 shows a distribution of skin alterations on the right ear which is quite uniform throughout from sector 3 to sector 19; on the left ear, there are two main groups of sectors on the upper and lower part of the auricle with a significantly greater cluster of skin alterations compared to the mean of the remaining sectors (Table 4.5A). It is possible that the reduced concentration of skin alterations on the remaining parts of the upper and lower conchae may be related to the more difficult visual access to these areas. Another possibility is that uneven or asymmetrical distribution of skin alterations in some sectors may be due to chance. This phenomenon in my opinion is worth particular consideration because it seemingly happens also if we apply the pain pressure test (PPT) (see Fig. 5.5) and electrical skin resistance test (ESRT) (see Fig. 7.1) in diagnostic procedures.

Table 4.5A Sectors in which the number of skin alterations in 357 patients was significantly higher than the average of points per sector according to the Getis-Ord local statistic Gi8,9

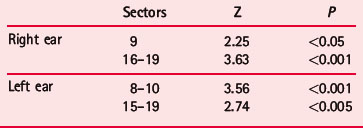

If we go back to the issue of asymmetrical distribution of skin alterations, we can see that the concentration of alignments on both auricles is not random but favors certain sectors above others. Cluster analysis indicates that sectors 9 and 16–19 on the right ear and 8–10 and 15–19 on the left ear have a significantly higher number of alignments than the average in the other sectors (Fig. 4.8; Table 4.5B).

Table 4.5B Sectors in which the number of alignments of two or more skin alterations was significantly higher in 357 patients than the average of alignments per sector, according to the Getis-Ord local statistic Gi8,9

If we consider the auricular parts on which the skin alterations are more often aligned we find the same part in 23.6%, anthelix with helix or with medial surface in 21.3%, followed by lower concha with ear lobe or antitragus in 14.5%. The second group of combinations appears to be related to the frequent occurrence of musculoskeletal problems in the aging population; the latter, however, seems to be associated with the presence of psychosomatic and metabolic disorders so common in contemporary patients.

THE INSPECTION OF THE OUTER EAR IN THE LITERATURE

1 THE DIAGONAL EAR LOBE CREASE OR FRANK’S SIGN

One of the most investigated auricular signs in the literature is undoubtedly the diagonal ear lobe crease (ELC). When Frank10 in 1973, in a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, described his ‘aural sign of coronary artery disease’ he cannot have imagined that he would trigger a long and unbroken series of researches all over the world. There are probably 40 or more reports and articles in the literature, written mainly by cardiologists, dealing with the following aspects of the question:

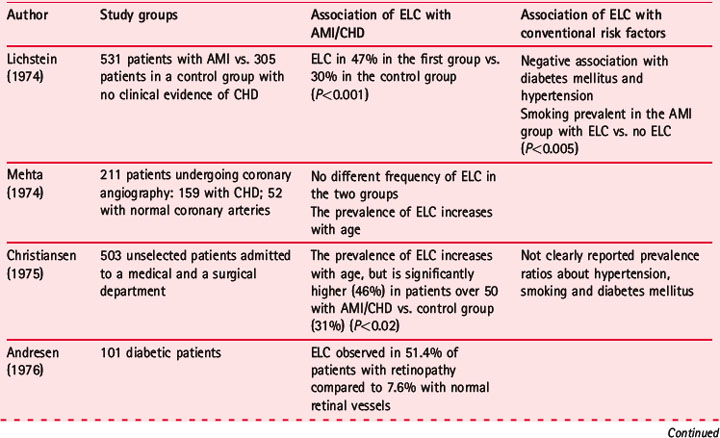

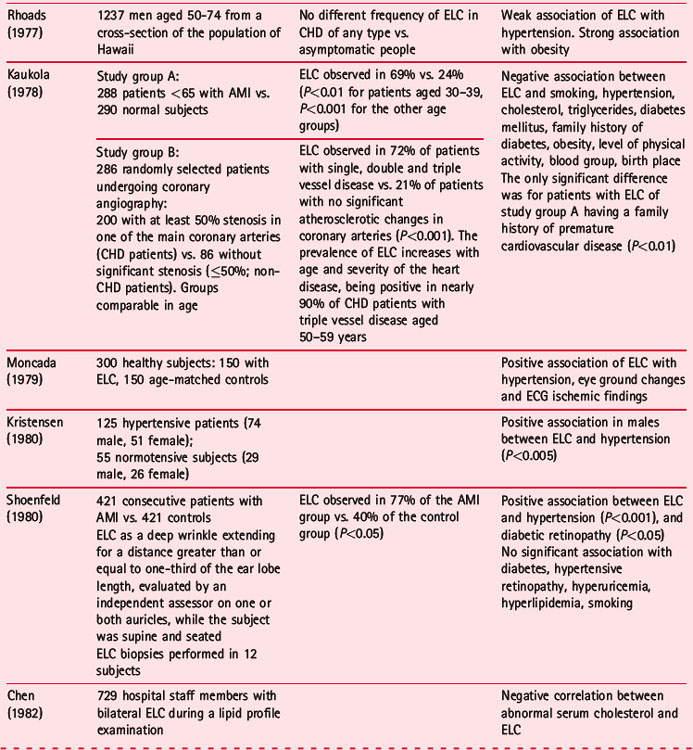

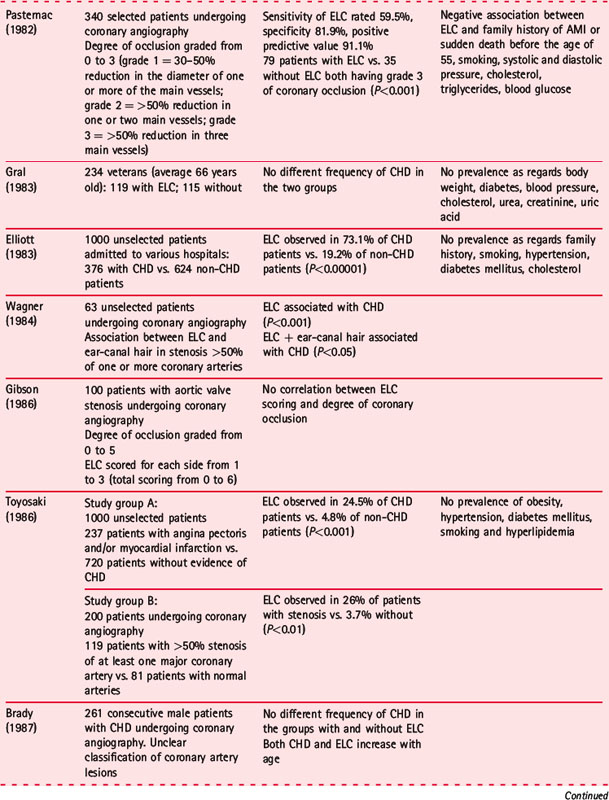

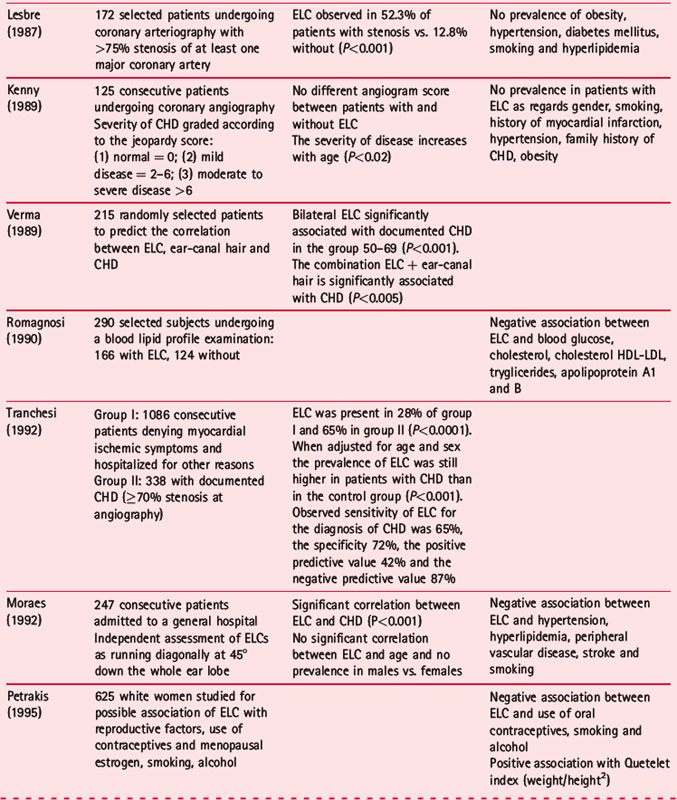

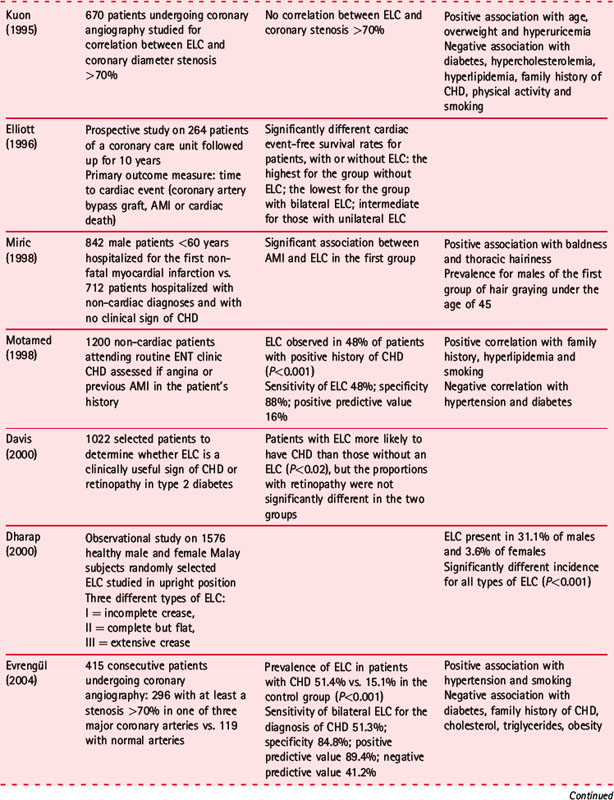

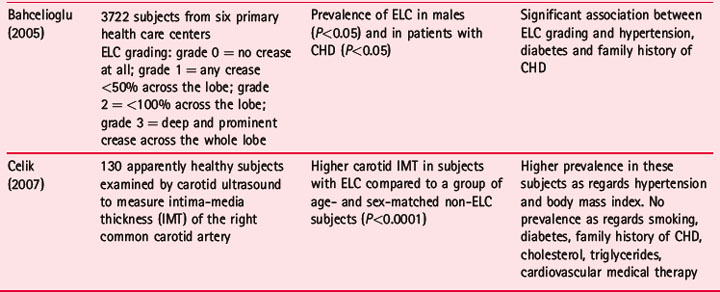

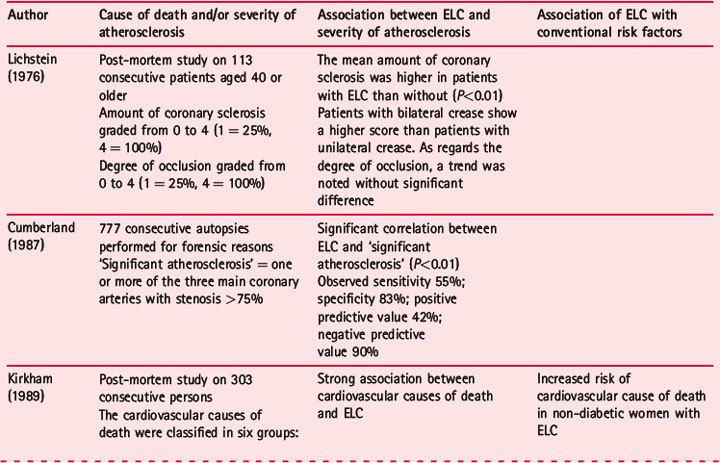

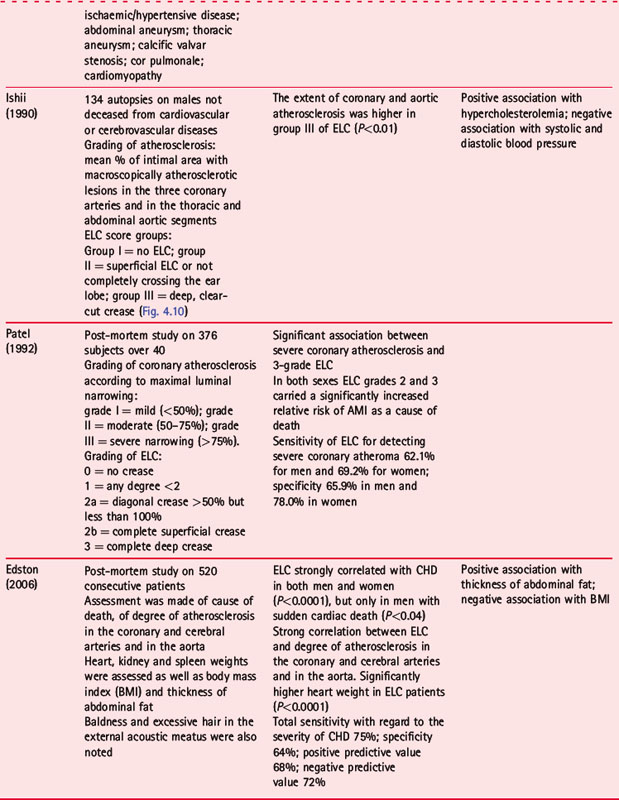

As regards the investigations carried out by cardiologists, Tables 4.6 and 4.7 report a (probably incomplete) list of articles published in the period between 1974 and 2007.11–49 While waiting for a complete systematic review on this topic the following information can be summarized from the tables:

Table 4.6 Study groups: association of ear lobe crease (ELC) with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and coronary heart disease (CHD); association of ELC with the conventional risk factors. A review of the literature 1974–2007

Table 4.7 Post-mortem studies on causes of death and severity of atherosclerosis (in coronary and in cerebral arteries, and in the aorta) in patients with ear lobe crease (ELC). A review of the literature 1976–2006

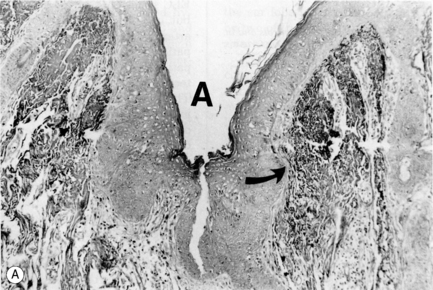

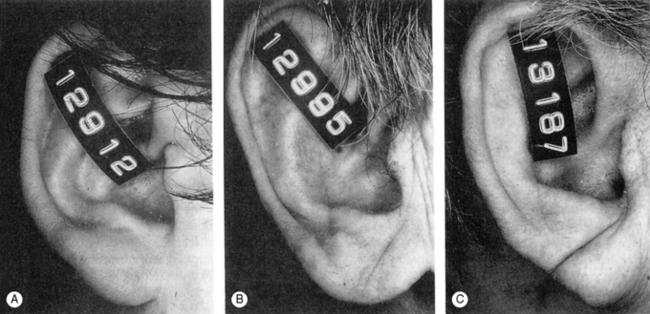

There are, however, some aspects which have not been considered sufficiently and which require a careful and reliable standardization of the crease. The first is that the ELC was rarely evaluated by independent observers; the second is that differences in interpretation of the crease itself may account for at least a part of the different results in comparing subjects with and without CHD. For example, it is rarely stated if the creases are observed with the patient in the upright or the supine position; the creases are more evident in the second position. What is perhaps more important is that not all the authors have reached a consensus that ELC has to be considered present if it appears to involve the full thickness of the skin, extending entirely across the ear lobe. Only in a few articles has the crease been measured in three different degrees, as in the post-mortem study47 shown in Figure 4.10.

However, the question that remains open for us is how to explain the topography of the crease and its relationship to the cardiovascular system. Cardiologist Yoshiaki Omura,50 who was involved early in the observation of ear lobe creases, tried to explain the relationship between the ear lobe and myocardial abnormalities by a common neural supply. The main part of the lobe being innervated by the great auricular nerve (C2–C3), he surmised that there could be an ‘unrecognized supply of small branches of nerves coming directly or indirectly from the heart’. He supported his hypothesis with the possible observation in cardiac patients of a radiating pain involving also the neck, chin and occipital area, covered indeed by the same supply, C2 and C3.

Johan Nguyen51 instead supposed that the correlation between a sign corresponding to the representation of the face and the heart could be explained only with the theory of TCM. He quoted as an example a sentence from the classical textbook Su Wen, Chapter 9, ‘The Heart is the source of life and the place of transformation of mental energy. Its energy manifests itself on the face.’

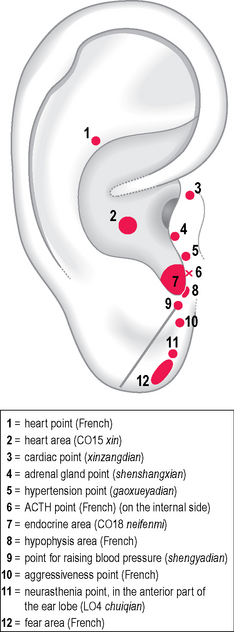

Concerning the starting point of the crease, Nogier’s map does not report any point related to the cardiovascular system in this area but shows the representation of the pituitary gland on the anterior ridge of the intertragic notch; the Chinese standardization, on the other hand, reports a puzzling tooth area (LO1 ya) with the indication for hypotension, besides toothache and periodontitis. The indication for raising blood pressure was maintained from the ancient map of the China Academy of TCM and is actually coincident with this starting point of the crease (Fig. 4.11). The possibility that this auricular area is related to dysfunctions of the cardiovascular system may be supported by the fact that just nearby on the tragus there are further points related to the heart such as xinzangdian of the ancient map, located within the current area TG1, with the indications of atrial fibrillation and tachycardia. Further points for treating hypertension are currently located in the area TG2 and adrenal gland shenshangxian located at the free border of the tragus between TG1 and TG2. The association of the tragus and the intertragic notch to diastolic pressure in hypertensive patients can be found in Chapter 5 (Figs 5.42, 5.43). As regards the possible association between CHD, ELC and ear-canal hair, which is supposed to be due to the long-term exposure to androgens, it is interesting from the topographic point of view that hair does not cover just the canal but also neighboring areas such as the tragus, the antitragus and the intertragic notch. All these areas appear to be involved in the regulation of neuroendocrine functions (Fig. 4.12).

The reader will allow me to make a short digression on this condition which belongs to the culture-bound syndromes of DSM IV but still survives in the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD-2-R).52–54 The Chinese translation for it is shenjing shuairuo where shen is emblematic of vitality and capacity of the mind to form ideas, jing originally refers to the meridians and channels carrying qi (vital energy) and xue (blood) through the body. Conceptually shen and and jing are treated by Chinese people and doctors as one term, shenjing, that means ‘nerve’ or ‘nervous system’. Shuai means decline, degeneration, and ruo weakness.54 At the end of this digression it has to be specified that the CCMD-2-R diagnostic criteria for shenjing shuairuo are any of three out of five groups of symptoms such as fatigue, dysphoria (restlessness, malaise), excitement, nervous pain and sleep disturbances. This syndrome, very popular at the end of the 1980s, is nowadays less and less diagnosed by Chinese psychiatrists who now favor a diagnosis of depression.

Returning to the second hypothesis, it is possible that ELC could be associated with the particular emotional status or personality trait of patients which seem to be recurrent in those developing some form of CHD. In the past I have been impressed by the representation of the rhinencephalon drawn by René Bourdiol,55 a neurologist who was also Paul Nogier’s closest collaborator. He dedicated his doctoral thesis to the interpretation of the different neural anatomical structures of the part of the CNS involved in ‘reaction behavior’ in humans. He described at least four neurophysiological systems:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree