48 Hip and Knee Pain

Imaging studies should be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Conventional radiographs should usually be the initial imaging study ordered.

Many of the vital structures in the knee can be palpated easily or examined with provocative tests.

A knee effusion is often associated with internal derangement.

Patients with osteoarthritis often complain of stiffness and pain with activity.

Groin pain with internal rotation of the hip is due to hip pathology until proven otherwise.

It is estimated that musculoskeletal pain affects one-third to one-half of the general population.1,2 Disease is occurring as the baby boomers have reached middle age and beyond. This is exemplified by the increasing prevalence of hip and knee replacement operations, which rose by 16.2% to 884,400 procedures annually in the United States between 2002 and 2004.3 Furthermore, the prevalence of total knee and total hip arthroplasty is expected to double by 2016 and 2026, respectively.4 The hip and knee joints are two of the most commonly affected sites of musculoskeletal pain, with the prevalence of hip pain ranging from 8% to 30% in persons 60 years of age and older5,6 and the prevalence of knee pain ranging from 20% to 52% in persons 55 years of age or older. In general, women experience more musculoskeletal pain than men.7 There are also geographic and ethnic variations in the rates of both hip and knee pain. For example, there tends to be significantly less hip and knee pain with decreasing latitude, as well as significantly less hip pain and osteoarthritis in China than in the United States.8–15

Knee Pain

Physical Examination

General

After a brief overall assessment of the patient, the physical examination should begin with observation of the patient’s lower extremity coronal alignment and leg lengths. We prefer to have the patient stand with legs slightly apart while he or she faces the examiner (Figure 48-1). A goniometer is then used to measure the varus/valgus alignment of the knees. Evaluation of leg lengths should be performed with step blocks of known sizes. The total height of the blocks needed to make the iliac crests level with the floor is equivalent to the leg-length discrepancy (Figure 48-2).

Figure 48-2 The total height of the blocks needed to make the iliac crests level is equal to the length discrepancy.

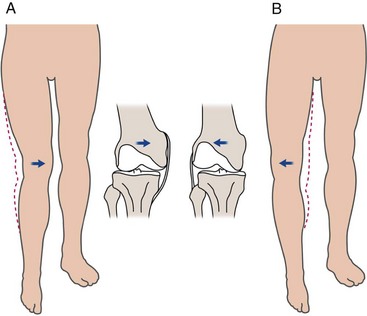

Gait is examined next. Although a comprehensive discussion of gait analysis is beyond the scope of this chapter, all clinicians should routinely make a few basic observations when evaluating the patient with a knee problem. Antalgic gaits (shortened stance phase) and thrusts are commonly seen. Any disorder that causes lower extremity pain may cause an antalgic gait. Seen in the stance phase of gait, thrusts may be due to a progressive angular deformity secondary to degenerative changes or chronic ligamentous instability. Medial thrusts result from medial collateral ligament and/or posteromedial capsular laxity. Lateral thrusts arise from lateral collateral ligament or posterolateral corner laxity (Figure 48-3). Patients may also thrust into recurvatum (so called back-knee deformity) due to posterior capsular laxity or quadriceps weakness.

Figure 48-3 The femur shifts medially during a medial thrust (A) and laterally during a lateral thrust (B).

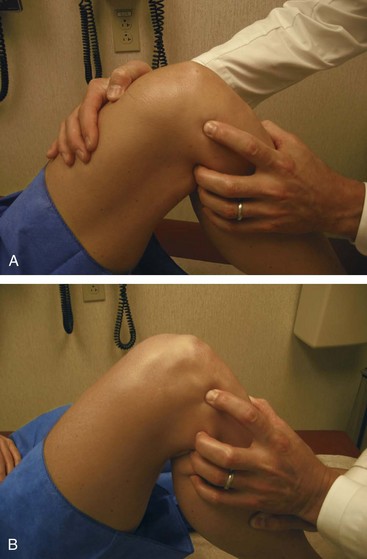

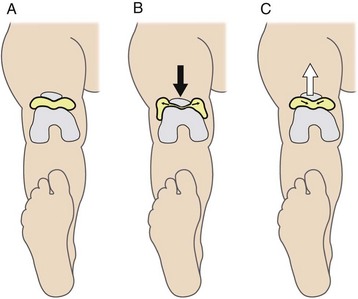

The patient should then transfer to the examination table for evaluation in a comfortable supine position. The examination should proceed with inspection and palpation before performing any provocative maneuvers. A pillow should be placed under the knee if full extension is not possible due to pain (e.g., fractures, displaced meniscus tears, large effusion). If there is no known pre-existing pathology, the contralateral knee can serve as an adequate control. The lower extremity should be inspected for any skin lesions, areas of ecchymosis, or surgical scars. Quadriceps atrophy should be noted, and a tape measure should be used to record thigh circumference. It is good practice to measure the thigh circumference at the same distance from the patella or joint line in each knee. The presence of an effusion should be noted. This will be seen as fullness or swelling in the suprapatellar pouch. The effusion should be confirmed by ballottement of the patella (Figure 48-4). Small effusions will require “milking” of the fluid upward into the suprapatellar pouch. This will allow for quantification of the amount of fluid (Figure 48-5). The active and passive range of motion of both knees should be recorded with a goniometer.

Figure 48-4 A-C, Large effusions can be detected by “ballotting” the patella with the knee in extension.

Figure 48-5 Small effusions can be appreciated by the “milking” of fluid into the suprapatellar pouch.

The examiner should then proceed with palpation of all structures of the knee. It is important to do this in a systematic manner to ensure completeness. Palpation should be gentle but firm enough to detect subtle pathology. Structures to be palpated include the quadriceps tendon, the patella (superior and inferior poles), the pes anserinus bursa, the medial (Figure 48-6A) and lateral (Figure 48-6B) joint lines, the origins and insertions of the collateral ligaments, the tibial tubercle, and the popliteal fossa. Fullness in the posterior knee may be indicative of a Baker’s cyst.

Ligaments

Injuries to the collateral or cruciate ligaments may lead to knee instability. It is important to mention that for each translational and rotational motion of the knee, there are both primary and secondary restraints. When a primary restraint is disrupted, motion will be limited by the secondary restraint. If a secondary restraint is injured and the primary restraint remains intact, then motion will not be abnormal. For example, the ACL is the primary restraint to anterior translation of the tibia, while the medial meniscus is the secondary restraint. ACL disruption will lead to a significant increase in anterior tibial translation. This translation will be increased if the patient had a prior medial menisectomy.16

The ACL is one of the most frequently injured structures in the knee. ACL insufficiency is also common in advanced osteoarthritis. Common mechanisms of injury include a direct blow to the lateral side of the knee (the “clipping” injury in football causing the triad of medial collateral ligament, ACL, and medial meniscus injuries17), as well as noncontact injuries that occur during cutting, pivoting, and jumping.18 Patients often report an audible “pop” accompanied by the acute onset of knee swelling. Multiple tests have been described to evaluate the ACL. The most sensitive tests for diagnosis of an ACL injury include the anterior drawer, Lachman,19 and pivot-shift tests.20,21 All three tests are performed with the patient in the supine position. The anterior drawer test is performed with the knee flexed to 90 degrees. The examiner places his or her hands on the posterior surface of the proximal tibia and subluxates the tibia anteriorly (Figure 48-7). Any gross movement of the tibia that is different from the contralateral side is considered abnormal. The Lachman test is performed with the knee in 30 degrees of flexion (to remove the contribution of secondary restraints). The examiner applies an anterior force on the tibia while stabilizing the femur with his or her contralateral hand. Any increase in anterior tibial translation relative to the contralateral side is considered abnormal (Figure 48-8). The pivot-shift test is performed with the knee in extension. The examiner holds the tibia in slight internal rotation and applies a valgus stress while the knee is slowly flexed. This combination of forces should cause the tibia to subluxate anteriorly if the ACL is injured. The test is positive if the tibia reduces with a “clunk” or a “glide” at 20 to 40 degrees of flexion (Figure 48-9).

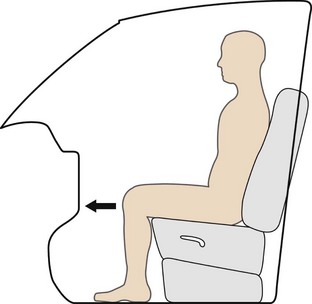

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is the strongest ligament in the knee,22,23 and thus injuries to the PCL are usually a result of significant knee trauma. The “dashboard” injury is a common mechanism for PCL injury and occurs during a motor vehicle accident when the flexed knee strikes the dashboard (Figure 48-10). The PCL can be evaluated with the posterior drawer, posterior sag, and quadriceps active tests. All tests are performed with the patient in the supine position. The posterior drawer test is performed with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion. The examiner applies a posteriorly directed force to the tibia. Placement of one’s thumb tips at the anterior joint line will allow for quantification of any abnormal translation (Figure 48-11). The posterior sag test is positive when the tibia subluxates posteriorly with the knee at 90 degrees of flexion. Loss of the medial tibial step-off at the joint line should alert the examiner to a PCL injury (Figure 48-12).22 This test is usually positive in the chronic setting or under anesthesia in the acute setting. The quadriceps active test is performed with the knee in 60 degrees of flexion. The patient is asked to extend the knee while keeping his or her foot on the examination table. One will see reduction of the tibia in a positive test.24

Figure 48-12 The posterior sag test is positive when the tibia subluxates posteriorly with the knee at 90 degrees of flexion.

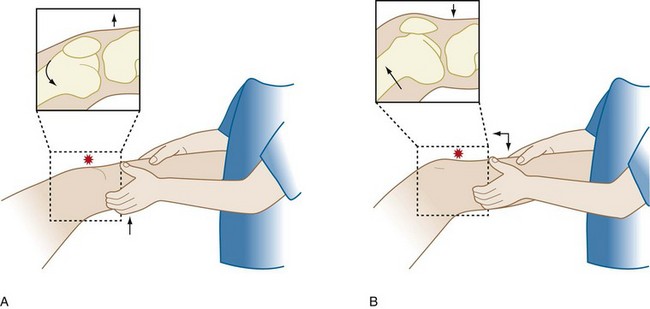

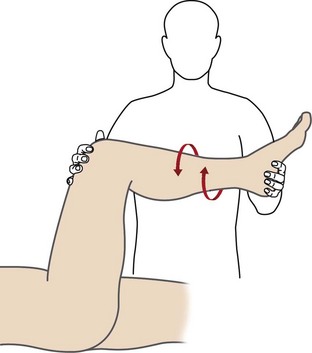

Injuries to the PCL are often accompanied by injuries to the posterolateral corner, a complex structure that functions as both a static and dynamic stabilizer of the knee.23 It is composed of the lateral collateral ligament, the popliteofibular ligament, the popliteomeniscal attachment, the arcuate ligament, and the popliteus tendon and muscle.25 Injuries to the posterolateral corner and/or the PCL can be examined with the “dial test” (Figure 48-13). The posterolateral corner structures restrain external rotation at 30 degrees of flexion, while the PCL restrains external rotation at 90 degrees of flexion. An increase of external rotation at 90 degrees of flexion without an increase in external rotation at 30 degrees of flexion suggests an isolated PCL injury. An increase of external rotation at 30 degrees of flexion without an increase at 90 degrees of flexion suggests an isolated injury to the posterolateral corner. Increased external rotation at both 30 degrees and 90 degrees of flexion suggests combined PCL and posterolateral corner injuries.

Menisci

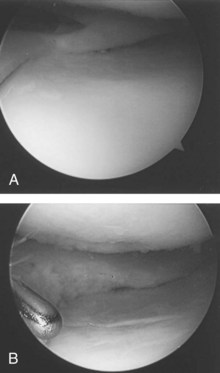

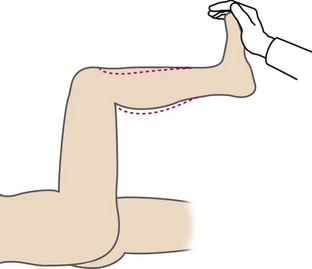

Meniscal tears usually occur with rotation of the flexed knee as it moves into extension. Tears of the medial meniscus are more common than tears of the lateral meniscus, likely due to the relative lack of mobility of the medial meniscus.26 Patients will frequently complain of “locking” and “clicking” or of something “wrong” with the knee, and this usually results from displacement of the torn meniscus during motion. Common physical findings include pain with hyperflexion and with hyperextension, joint line tenderness, and an effusion. Many provocative tests have been described to diagnose meniscal tears. The McMurray27 and Apley compression28 tests are frequently performed, though they do lack sensitivity and specificity. The flexion McMurray test is performed with the patient supine and the hip and knee flexed to 90 degrees. A compressive and rotational force is applied to the knee as it is moved from a flexed to an extended position. The test is positive if the patient complains of pain (Figure 48-14). The Apley compression test is performed with the patient prone and the knee flexed to 90 degrees. In a positive test, the patient will complain of pain with rotation of the tibia. An arthroscopic photograph in Figure 48-15 shows a tear in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.

Quadriceps Tendon

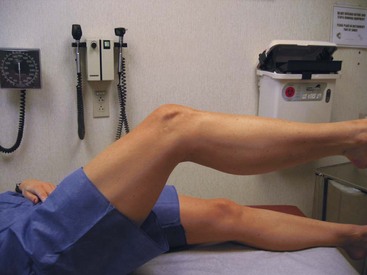

Injuries to the quadriceps tendon are most common in the sixth and seventh decades of life. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, renal failure, endocrinopathies, diabetes, and various other systemic inflammatory and metabolic diseases tend to be at a higher risk for these injuries. The prevalence of quadriceps tendon rupture after total knee arthroplasty is a rare (0.1%) but devastating complication.29 Patients usually present with intense anterior knee pain after experiencing an eccentric quadriceps contraction during a fall or twisting injury. Physical examination reveals a palpable defect in the tendon, an effusion due to hemarthrosis, and hypermobility of the patella. Patients will usually not be able to fully extend their knee (Figure 48-16).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree