Hallux Valgus, Hallux Varus, and Sesamoid Disorders

Jeffrey A. Mann

INTRODUCTION

Hallux valgus deformity refers to a lateral deviation of the great toe at the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. Although this description sounds relatively simple, hallux valgus is a complicated anatomic deformity and is challenging to treat. The term bunion refers to the prominent medial eminence that is present in a hallux valgus deformity, but in general these terms are used interchangeably. It is important to note that although clinically a bunion may appear to be an exostosis, it is actually the misaligned first metatarsal head that is prominent. Hallux valgus is the most common pathologic condition affecting the great toe. It most likely occurs as a combination of genetic predisposition and prolonged wearing of shoes that place abnormal pressure on the first toe.

Despite its common occurrence, there is little consensus as to the best treatment method of hallux valgus. Dozens of surgical procedures have been described to correct the deformity. When evaluating a patient with hallux valgus, it is essential to determine the primary complaint and expectations of treatment, such as whether the patient desires relief of pain or the ability to wear certain shoes. When surgery is contemplated, it is critical to carefully evaluate the patient’s foot clinically as well as radiographically to determine the best procedure(s) to correct the deformity. This chapter focuses on the evaluation of bunion deformities and the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate surgical procedure to correct a bunion deformity. Juvenile bunions differ substantially from adult hallux valgus and therefore a separate section on this entity is included.

Hallux varus deformity is uncommonly encountered and is most often a result of failed bunion surgery. The etiology of hallux varus as it relates to bunion surgery, and its treatment options are discussed in this chapter.

The third section in this chapter reviews sesamoid disorders of the hallux. These disorders fall into the categories of acute fractures, osteonecrosis, sesamoiditis, painful subluxation, and degenerative changes. Diagnosis and treatment for these sesamoid disorders are discussed.

HALLUX VALGUS

PATHOGENESIS

Etiology

Bunion deformities are 15 times more prevalent in populations where shoes are worn than in populations where they are not. Footwear that constricts the forefoot appears to be the primary causative factor for development of a hallux valgus deformity. However, because bunions do not develop in all people who wear such shoes, there must be other predisposing factors.

Heredity appears to play a role in development of a bunion, especially the juvenile form; a positive family history has been reported in many studies. Metatarsus primus varus, medial angulation of the first metatarsal at the metatarsocuneiform joint, may also be a predisposing factor for development of a bunion, especially in juvenile bunions as observed in a high percentage of patients. Bunions are also more common in patients with systemic arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis, wherein the synovial inflammation causes attenuation of the MTP joint capsule and leads to the hallux valgus deformity.

The association of bunions in patients with flat feet and in those with Achilles tendon contractures has been hypothesized. Patients with severe flat feet as a result of generalized ligament laxity are more susceptible to bunions because of the lack of ligament stability. However, most patients with mild-to-moderate flat feet do not have a higher incidence of bunion deformities.

Hypermobility of the first metatarsocuneiform joint may play a role in the development of bunions in a small percentage (probably <5%) of patients. This concept is controversial because the obliquity of this joint makes it difficult to measure its motion by any standard means. Some authors attribute a majority of bunion deformities to hypermobility of the first metatarsocuneiform, but there is a paucity of data to support this hypothesis.

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

Normal Anatomy of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint

The pathophysiology of hallux valgus deformity is a function of the unique anatomic relationships of the first MTP articulation. Even though no muscle inserts onto the metatarsal head, it lies in a sling of muscles and tendons. Its position is related to the position of the proximal phalanx, which has multiple muscle and tendon attachments. To understand how a bunion deformity develops and how best to treat it, a thorough understanding of the first MTP joint anatomy is necessary.

On the plantar aspect of the first MTP joint lies the plantar plate complex. The plantar plate comprises the joint capsule, the tendons of the flexor hallucis brevis, the plantar portions of the abductor and adductor hallucis tendons, and portions of the medial and lateral collateral ligaments (Fig. 6.1). The sesamoids lie within the tendons of the flexor hallucis brevis and articulate with facets on the plantar surface of the metatarsal head, which are separated by a ridge or crista. The plantar plate and sesamoid complex are attached to the base of the proximal phalanx. The flexor hallucis longus tendon runs on the plantar aspect of this sesamoid complex and inserts onto the distal phalanx.

The medial aspect of the first MTP joint is stabilized by the fan-shaped medial collateral ligament, which runs from the medial epicondyle of the metatarsal head to the proximal phalanx and the medial sesamoid. The stout abductor hallucis tendon also attaches to the medial sesamoid and plantar aspect of the base of the proximal phalanx. Similarly, the lateral aspect of the MTP joint is stabilized by the lateral collateral ligament and the two heads of the adductor hallucis tendon, which attach to the base of the proximal phalanx, the plantar plate, and the lateral sesamoid.

On the dorsal aspect of the first MTP lies the extensor hood, which attaches the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) to the sides of the base of the proximal phalanx. The extensor hallucis brevis (EHB) lies beneath the hood ligament and attaches to the base of the proximal phalanx as well.

Pathophysiology of Bunion Deformity

Before discussing the pathophysiology of bunions, a few important concepts about the first MTP joint must be emphasized.

The shape of the first metatarsal head articular surface is variable and therefore has a bearing on the development of a bunion deformity. A round head is less stable than a flat head and therefore more prone to develop angulation.

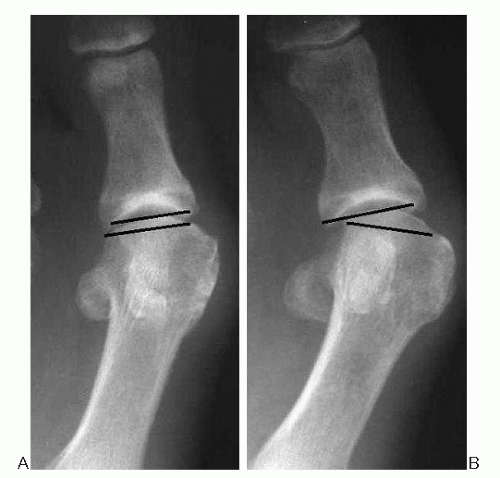

The distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA), which measures the relationship of the articular surface to the long axis of the first metatarsal, is also variable and may greatly influence a bunion deformity (Fig. 6.2).

Joint congruence measures the relationship between the articular surface of the first metatarsal head and the articular surface of the proximal phalanx

In a congruent joint, the two articular surfaces are parallel to one another (Fig. 6.3).

In an incongruent or subluxed joint, the two articular surfaces are not parallel.

Although bunions can be classified in numerous ways, it is helpful from the standpoint of pathophysiology to classify bunions into progressive and nonprogressive deformities. A progressive bunion deformity usually starts as a normal or minimally angulated MTP joint that is unstable as a result of a round articular surface. Prolonged exposure to valgus force on the first toe, such as it occurs with the use of tight shoes, begins to cause a slight angulation of the toe. Alternatively, a genetic predisposition to valgus angulation may influence the unstable joint. Once established, the valgus angulation tends to worsen with time because of the

muscular pull of the EHL and adductor hallucis tendons on the proximal phalanx and a valgus stress during the toe-off phase of gait. Any valgus force on the proximal phalanx causes a resultant medially directed force on the metatarsal head. This contributes to a varus angulation of the first metatarsal shaft (metatarsus primus varus). Over time, the medial joint capsule becomes elongated, and the lateral joint capsule becomes contracted.

muscular pull of the EHL and adductor hallucis tendons on the proximal phalanx and a valgus stress during the toe-off phase of gait. Any valgus force on the proximal phalanx causes a resultant medially directed force on the metatarsal head. This contributes to a varus angulation of the first metatarsal shaft (metatarsus primus varus). Over time, the medial joint capsule becomes elongated, and the lateral joint capsule becomes contracted.

Figure 6.2 The DMAA measures the relationship of the articular surface of the metatarsal head to the long axis of the first metatarsal. The angle is the deviation from a right angle. |

As the metatarsal head deviates medially, the sesamoid sling is held in place by strong attachments of the transverse metatarsal ligament and adductor hallucis muscle leading to lateral subluxation of the sesamoids under the metatarsal head (Fig. 6.4). On the medial aspect of the joint, attenuation of the capsular complex occurs just dorsal to the abductor hallucis tendon because this region is the weakest portion of the medial capsule. Therefore, as the

metatarsal head deviates medially and the proximal phalanx deviates laterally, the abductor hallucis tendon slides underneath the metatarsal head. The attachment of the abductor hallucis tendon on the proximal phalanx causes the entire first toe to rotate around its axis into pronation. As the proximal phalanx is rotated around the metatarsal head, an incongruent or subluxed joint is created.

metatarsal head deviates medially and the proximal phalanx deviates laterally, the abductor hallucis tendon slides underneath the metatarsal head. The attachment of the abductor hallucis tendon on the proximal phalanx causes the entire first toe to rotate around its axis into pronation. As the proximal phalanx is rotated around the metatarsal head, an incongruent or subluxed joint is created.

The mechanism whereby bunions occur in nonprogressive joints is different. These deformities usually occur in congruent joints because of to anatomic features. Occasionally, an enlarged medial eminence may be present that exerts pressure on the medial side of the foot, causing a painful bursa or impingement on the cutaneous nerves. In other cases, patients have lateral deviation to the articular surface of their metatarsal head (an increased DMAA). A large enough deformity of this type causes a prominent medial eminence and varus tilting of the first metatarsal shaft. This deformity is more stable and less likely to progress because of a congruent MTP joint, but it may still be painful if the deformity is severe.

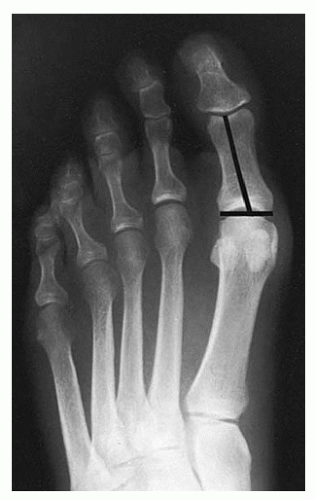

Hallux valgus interphalangeus is defined as a valgus deformity of the great toe due to valgus angulation of more than 10° of the proximal or distal articular surface of the proximal phalanx in relation to the long axis of the proximal phalanx (Fig. 6.5). Hallux valgus interphalangeus tends to be a nonprogressive deformity.

DIAGNOSIS

History

Although a diagnosis of a bunion deformity is usually straightforward, the history yields important information about the etiology of the patient’s symptoms and expectations. The chief complaint is usually pain. Pain can be located diffusely around the MTP joint, or it may be more localized over the medial eminence, dorsal MTP joint, beneath the sesamoids, or along the cutaneous nerves. Pain may also occur from lesser toe deformities or from transfer metatarsalgia lesions underneath the lesser metatarsal heads. Other concerns include inability to wear certain shoes, limitation of physical activities, and the appearance of the foot.

Other important factors include a history of surgery on the foot or ankle and general medical problems, including a history of gout, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, or peripheral vascular disease. Occupational demands are important, especially the amount of time a patient spends on his or her feet and whether heavy labor is performed. Activities that exacerbate pain, such as walking, jogging or running, and hill or stair climbing, should be noted. Noting whether the pain is worsened by wearing certain types of shoes or going barefoot and noting what footwear modifications have been made are important.

A critical issue when obtaining a history is the patient’s expectations of the treatment. Expectations should include decreasing pain and increasing activity, but patients should not have unrealistic footwear expectations. Some physical activities may be limited after bunion surgery, including long-distance running, aggressive pivoting sports, and ballet dancing; forewarning patients of possible limitations is important.

Physical Examination

Clinical Features

The physical examination begins with the patient standing to assess the degree of hallux valgus, lesser toe deformities, and posture of the longitudinal arch.

With the patient seated, a comprehensive examination of the hindfoot and forefoot is performed.

The medial eminence is observed for its degree of prominence and presence of a callus or painful bursa (Fig. 6.6).

The first MTP joint is evaluated for the range of motion, swelling, and the presence of dorsal bone spurs.

Joint range of motion is compared with that of the opposite foot.

If motion is limited and exostoses are present, this indicates that some degree of osteoarthritis is present.

The MTP joint should be palpated for tenderness dorsally, medially, and on the plantar surface.

On the plantar surface, localized sesamoid pain (which tends to be located proximal to the joint with the MTP joint held in neutral) should be noted.

Neuritic pain should be elicited from the dorsal or plantar cutaneous nerves, especially when there is a complaint of numbness or tingling in the hallux.

The mobility of the first metatarsocuneiform joint is determined by grasping the foot proximal to this joint and then moving the first metatarsal and comparing it with the opposite foot with the ankle in neutral position. More than 7° to 10° of motion indicates hypermobility at this joint.

As a simple test to assess joint congruity and flexibility of the deformity, one can manually straighten the hallux valgus deformity and move the MTP joint.

This test can help to determine the amount of correction that can be obtained at surgery without compromising motion at the MTP joint.

If the patient has a congruent bunion deformity, straightening the toe at the MTP joint makes it incongruent and therefore limits motion.

This test is less reliable with a severe bunion deformity in which significant soft-tissue contractures are present at the MTP joint.

The lesser toes should be evaluated for hammer toes, MTP joint instability or dislocation, and plantar pain or callosities, especially underneath the second metatarsal head.

Evaluation of the neurovascular status is important.

Overall perfusion of the foot is determined by capillary refill of the digits and palpation of pulses.

If there is a question about the vascular status, appropriate diagnostic studies should be carried out.

Careful neurologic examination helps to determine whether there is preexisting peripheral or cutaneous nerve damage that may be contributing to the patient’s symptoms.

Radiologic Features

Weight-bearing radiographs are essential for accurate evaluation of hallux valgus deformity. Several features need to be assessed on these radiographs:

Hallux valgus angle: The angle between lines bisecting the first metatarsal and proximal phalanx: normally less than 15° (Fig. 6.7).

Intermetatarsal angle: The angle between lines bisecting the shafts of first and second metatarsals: normally less than 9° (Fig. 6.8).

DMAA: Measure of the articular surface of the first metatarsal head, as it relates to the long axis of first metatarsal (Fig. 6.2): normally less than 10° of lateral deviation of the articular surface of the metatarsal head.

Figure 6.7 The hallux valgus (HV) angle measures the angle between the first metatarsal and the proximal phalanx.

Joint congruity: Assesses whether the joint surfaces of the metatarsal head and proximal phalanx are subluxated: if the joint margins are offset, the joint is incongruent (Fig. 6.3).

Interphalangeal angle: Angle between lines bisecting the proximal and distal phalanges of the first toe: normal, less than 10°.

Joint arthrosis: Severity noted.

Sesamoid position: Some degree of subluxation of the sesamoids from beneath the meatatarsal head is inevitable. Although it is not usually considered preoperatively, its correction intraoperativly is essential.

Bunions Are Classified by Their Severity

Mild bunion: Hallux valgus angle less than 30°, intermetatarsal angle less than 13°. The joint is usually congruent, and the deformity may be due to a hallux valgus interphalangeus.

Moderate bunion: Hallux valgus angle between 30° and 40°, intermetatarsal angle between 13° and 20°. MTP joint usually incongruent (subluxed); hallux is pronated and often presses against the second toe.

Severe bunion: More than 40° hallux valgus angle, intermetatarsal 20° or more. Hallux is pronated and often overlapping or underlapping the second toe; MTP joint incongruent; frequently painful transfer lesion underneath the second metatarsal head; possible arthritic changes.

TREATMENT

Conservative Treatment

The cornerstone of conservative treatment is footwear modification. If the primary problem is a painful medial eminence caused by an advanced bunion, then wearing shoes with a wide toe box or open-toed shoes can minimize rubbing over the medial eminence. Bunion pads, night splints, and toe spacers may provide temporary relief, but tend to be of little help in the long term. Similarly, custom orthotics do not usually provide lasting pain relief. However, if the symptoms are primarily pain underneath the sesamoids or transfer lesions underneath the lesser metatarsal heads, soft pads can be placed in the shoes just proximal to these prominences to alleviate pressure from the painful areas. If lesser-toe deformities are the chief complaint, these can also be addressed with wide or open-toed shoes, or commercially available toe sleeves. Contraindications to surgical treatment are considered in Box 6.1.

Surgical Treatment

If conservative measures have failed to relieve symptoms from a hallux valgus deformity, surgical correction of the bunion can be offered. The anatomic deformity and other factors considered are as follows:

The patient’s main complaint, profession, and athletic pursuits.

The physical examination findings, including the severity of deformity, the area of maximum tenderness, and associated lesser toe deformities.

Radiographic evaluation, including the parameters discussed previously.

The neurovascular status of the foot.

The patient’s expectations of the operative procedure.

BOX 6.1 CONTRAINDICATIONS TO SURGICAL TREATMENT OF HALLUX VALGUS

Absolute

Active infection of the MTP joint

Poor vascularity

Unreliable

Unable to participate in the postoperative regimen of dressing changes

Relative

Mild arthritis or arthrofibrosis

Unrealistic expectations

Not all professional or high-level athletes can return to full function after bunion surgery because of limited motion, diminished strength, or residual discomfort. If a patient’s complaint is lesser-toe deformities or transfer lesions, correction of the bunion may be the only way to alleviate the problem by restoring proper weight bearing to the first ray and by providing room to straighten out the lesser toes especially the second toe.

Patients must be made fully aware about the time necessary to return to work or athletics after surgery. Furthermore, patients must be warned of the possible postoperative appearance of their foot. Mild residual deformity resulting from anatomic factors (e.g., mild hallux valgus interphalangeus), incomplete correction at surgery, or mild postoperative recurrence of the bunion may be present.

Decision-Making Algorithm

A single surgical procedure cannot be used to correct the different types of bunions. Radiographs guide the decisionmaking algorithm. If the MTP joint is congruent, any surgical procedure that is contemplated must not change the relationship of this articulation. With an incongruent joint, soft tissues require rebalancing, which rotates the proximal phalanx back onto the metatarsal head, recreating a congruent joint.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree