, Michael J. Salata4 and Shane J. Nho2, 3

(1)

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Midwest Orthopaedics at Rush, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA

(2)

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA

(3)

Midwest Orthopaedics at Rush, Hip Preservation Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA

(4)

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Joint Preservation and Cartilage Restoration Center, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, USA

Abstract

As techniques in minimally invasive hip surgery evolve, there is increasing opportunity to treat peritrochanteric hip conditions endoscopically. The collective diagnosis of greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) includes trochanteric bursitis, gluteus medius and minimus tears, and external snapping hip syndrome (coxa saltans). Most of these conditions can be accurately diagnosed with routine history and physical examinations aided by plain radiographs, MRI, CT scans, and ultrasonography. Nonsurgical treatment is generally the first line of treatment and most conditions will improve with oral anti-inflammatories and directed physical therapy programs. Diagnostic and therapeutic injections are useful in narrowing down the diagnosis and may also provide treatment for many ailments outside the hip joint. Minimally invasive surgical interventions via endoscopy have expanded dramatically in this area and continue to grow as we further understand the treatment pathology and select appropriate patients for surgery.

Introduction

Indications for hip arthroscopy have expanded greatly over the past decade, and it remains one of the areas with greatest growth in orthopedic surgery. Current diagnostic and treatment regimens have allowed for considerable advancements in treatment for both intra-articular and extra-articular hip conditions. With the growth seen in the minimally invasive treatment of intra-articular hip conditions, surgeons are now venturing extracapsular to treat soft tissue ailments. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a relatively common clinical entity that is seen in 10–25 % of the general population [1] that encompasses disorders of the lateral, peritrochanteric space of the hip including trochanteric bursitis , tears of the gluteus medius and minimus tendons, and external coxa saltans (snapping hip). Patients generally experience reproducible pain over the greater trochanter, buttocks, or lateral thigh, and the condition is seen with increased incidence in patients with low back pain [2] and increased prevalence in women [1]. Endoscopy provides improved visualization of extra-articular pathology that previously required large open incisions for diagnosis and treatment. Specific to greater trochanteric pain disorders, endoscopic approaches are now effective in providing extra-articular access to the iliotibial band in external coxa saltans, debridement of recalcitrant trochanteric bursitis, and endoscopic repair of gluteus medius tears. The purpose of this chapter is to characterize the anatomy and diagnosis of greater trochanteric pain disorders while providing nonoperative and operative treatment options.

Relevant Anatomy

The greater trochanter lies at the junction of the femoral neck and shaft and is the site of attachment of the gluteal, obturator, and piriformis tendons. The peritrochanteric space consists of the gluteus medius and minimus tendons, iliotibial band, and greater trochanter with its associated bursa. The gluteus medius inserts into the superoposterior and lateral facets of the greater trochanter while the gluteus minimus tendon attaches to the anterior facet. A fibromuscular sheath composed of the gluteus maximus, tensor fascia lata (TFL), and iliotibial band (ITB) lies superficial to these tendons.

Three bursae in the vicinity of the greater trochanter serve to cushion the gluteal tendons, the ITB, and the TFL. The subgluteus medius bursa lies over the lateral facet with the subgluteus minimus bursa sitting deep to the tendon around the anterior facet and anterior hip capsule. The largest bursa, the trochanteric or subgluteus maximus bursa, sits deep to the fibers of the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata (TFL) as they form the iliotibial band (ITB). This bursa sits on top of the posterior facet of the greater trochanter, the distal-lateral gluteus medius tendon at the lateral facet, and the proximal vastus lateralis insertion [3]. The gluteus medius and minimus tendons function in a similar manner to the rotator cuff, helping to stabilize the hip joint and initiate abduction [4]. Tears generally occur in the footprint on the greater trochanter and can be intra-substance, partial, or complete [5]. External snapping hip generally occurs secondary to thickening of the posterior IT band, tensor fascia lata, or gluteus maximus as they slide over the greater trochanter during hip flexion.

Disease Presentation

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) encompasses a broad category of diagnoses and is characterized by lateral-sided hip pain and includes trochanteric bursitis, gluteus medius or minimus tears, and external coxa saltans [6, 7]. Trochanteric bursitis refers to inflammation of at least one of the three aforementioned trochanteric bursae and is thought to result from gait abnormalities, trauma, or repetitive activity [8]. It often involves pain localized to the greater trochanter that radiates down the lateral thigh or into the buttocks caused by repetitive friction between the ITB and greater trochanter with hip flexion and extension. Patients presenting with trochanteric bursitis generally have other associated pathology such as osteoarthritis of the ipsilateral hip or lumbar spine [9], but the disease is now being seen more commonly in younger patient populations [10, 11].

Gluteus medius or minimus tears are the most common presentation and are often found in patients with recalcitrant trochanteric bursitis [12, 13]. Recent studies have suggested that tears will occur in 25 % of middle-aged women and 10 % of men of similar age [14]. This increased incidence in women may be secondary to the wider female pelvis [15]. The natural progression of hip abductor tendinopathy is similar to the pathogenesis of tendon degeneration elsewhere in the body and generally begins with bursitis before progressing down the spectrum of tendonitis, tendinopathy, partial thickness tearing, full thickness tearing, and massive tears. Chronic massive tears of the abductors may lead to significant fatty infiltration and atrophy of the gluteal muscles, which may lead to a guarded functional prognosis following repair.

External snapping hip syndrome is often secondary to thickening of the posterior third of the IT band (ITB) that lies posterior to the greater trochanter when the hip is in a neutral position [16]. Repeated flexion and extension of the overly taut ITB will result in mechanical symptoms as the ITB catches on the greater trochanter. Further tightening of the ITB and its resultant “snapping” is exacerbated by hip adduction and extension at the knee [17]. Women with prominent greater trochanters or a larger pelvis have a predilection for external snapping hip. This is most commonly seen in women who adduct beyond their midline during gait [17]. The snapping of the ITB itself is usually non-painful [16] but can lead to inflammation of the trochanteric bursa from the abrasive wear [18]. Kingzett-Taylor et al. [7] suggested that both abductor tendinopathy and trochanteric bursitis could be secondary to frictional trauma caused by high ITB tension. This supports the notion that causes of GTPS are multifactorial and can influence each other.

Patient History

Inflammation in the region of the greater trochanter can result in radiating pain and paresthesias that can lead to a wide and confusing initial differential diagnosis list. Patients may report a constellation of varying degrees of buttock, lateral hip, and groin pain which is due, in part, to the varying nervous supply of the peritrochanteric compartment. Patients may complain of lateral hip pain that is exacerbated by direct pressure, prolonged standing or upright activity, and activities that engage the hip abductors such as getting up from a seated position or climbing stairs. They may also report pain in a lateral decubitus position that wakes them up at night. Additionally, in most cases, the onset of symptoms is insidious, but there are some patients that report an acute exacerbation of symptoms after a specific event [19]. Patients presenting with external snapping hip syndrome may describe a snapping sensation that occurs with exercise or routine daily activities.

Physical Examination

Physicians must be certain to rule out spine pathology as a cause of symptoms. Patients suffering from a gluteus medius avulsion may present with an obvious limp [20, 21]. Additionally, certain anatomic abnormalities such as a high valgus knee angles and leg length discrepancies have been known to cause mechanical abrasion and subsequent abductor tears due to increased ITB tension [16]. Physical examination specific to the hip begins with observation of the patient for Trendelenburg gait followed by performing the Trendelenburg fatigue test. A distinct drop of the unsupported side of the pelvis indicates weakness or loss of function of the abductors. Positive findings on this test may be suggestive of possible abductor insufficiency. With the patient in a lateral decubitus position, the anterior, lateral, and posterior aspect of the greater trochanter is palpated for tenderness. Abductor strength testing can be performed in both knee flexion and extension to enable gravity strength testing.

Provocative maneuvers can be performed including the trochanteric pain sign, which is performed with the patient in a supine position. With the hip flexed to 90°, it is then abducted and externally rotated (see Fig. 1). The test is considered to be positive if there is pain with external rotation. Additionally, flexion, abduction, external rotation, and extension (FABERE) testing may also elicit pain in patients with GTPS (see Fig. 2). Resisted external rotation should also be performed while the patient is in the supine position with the hip flexed at 90° [5, 22].

Fig. 1

The trochanteric pain sign is elicited with the patient supine and the hip in 90° of flexion by abducting and externally rotating the hip

Fig. 2

FABERE testing is performed with flexion, abduction, external rotation, and extension of the hip

The physical exam for external snapping hip syndrome generally reveals a palpable or observable snapping of the ITB over the greater trochanter upon flexion and subsequent extension. The patient can be placed in a lateral decubitus position, and a single leg bicycle maneuver can be performed which may reproduce ITB snapping. The diagnosis can be confirmed if pressure applied over the superior greater trochanter prevents snapping with repeated hip flexion. A positive OBER test resulting in significant tightening of the ITB may be seen and would qualify the patient as a good candidate for ITB release along with removal of the symptomatic bursa [23].

Diagnostic Imaging

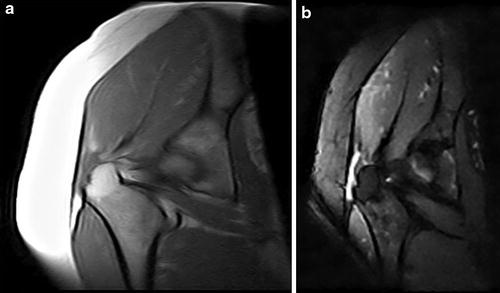

Plain radiographs should be obtained to rule out osteoarthritis and can also demonstrate evidence of calcific tendonitis or intra-bursal calcifications. They are generally low yield for gluteus medius and minimus tears but can identify trochanteric osteophytes that the gluteal tendons may be draped over. MRI and ultrasonography are the primary imaging modalities used to diagnose tendon pathology. Specific findings in GTPS may include enthesopathic changes along the trochanteric insertion, subminimus and submedius bursitis, and fatty atrophy of the associated muscle bellies [16]. On T2-weighted MRI, hyperintensity superior and lateral to the greater trochanter is often seen due to either thickened hip abductor tendons, tendinopathy, or tendon tears (see Fig. 3a and b). Tendon discontinuity may be seen on T1 images. MRI can also be used to gauge the degree of fatty infiltration and atrophy of the abductor muscle complex. Though the overall specificity of MRI is debated [24], Kingzett-Taylor et al. found T2-weighted MRI of the superior greater trochanter to be diagnostic for partial abductor tendon tears with high sensitivity (73 %) and specificity (95 %) [7], but false positive rates have been reported to be as high as 88 % in one series [25]. Ultrasound may be a reliable alternative to MRI in the diagnosis of gluteus medius and minimus tears, with a sensitivity of 79 % and a positive predictive value of 100 % [26]. Dynamic real-time ultrasound can also be used to visualize snapping hip and identify inflamed trochanteric bursa.