In this chapter, we discuss self-care and activities of daily living (ADL) from the standpoint of rehabilitation across a wide range of ages and conditions. We first describe the importance of this domain of human activity to illustrate why self-care and ADL performance are important rehabilitation goals. We then describe approaches to assessing an individual’s ADL skills, sampling the range and scope of assessments in this area that are supported by published research. We attempt to identify best practices and areas of philosophical and procedural controversies. Finally, we turn to the intervention strategies. A collaborative goal-setting process to guide intervention is emphasized. We summarize key intervention strategies across a sample of conditions, citing evidence in support of intervention strategies, where available.

Enabling individuals to manage daily self-care is among the most important tasks undertaken by the rehabilitation team. This is because such tasks relate directly to the business of living and their performance signifies a return to participation in the routines of daily life. Self-care tasks include dressing, eating, bathing, grooming, use of the toilet, and mobility within the home. These are basic tasks included within the general category of ADL. Although able-bodied persons perform most self-care tasks routinely, such tasks can represent difficult challenges for persons with sensory, motor, and/or cognitive deficits.

Unfortunately, there is no consensus on the classification of human activity. As a result, many terms with similar definitions used for ADL categories are used in the medical, health, and rehabilitation literature.

Table 9-1 lists some of these. In this chapter, basic ADLs (BADL), such as eating, dressing, grooming, hygiene, and mobility, are described as personal or self-care tasks. Essential tasks for maintaining the living environment and residing in the community are described as IADLs or EADLs (see

Table 9-1).

In the developed nations, about 30% of a typical person’s waking hours is spent performing self-maintenance activities, including basic self-care and household maintenance (

5,

6). For able-bodied persons, an average of more than 1 hour per day is spent in basic self-care activities (

7). Research has shown that more than 70% of the variation in discharge decisions following stroke rehabilitation is determined by the ability to function independently self-care tasks necessary for bathing, toileting, social interaction, dressing, and eating (

8,

9).

Self-care and ADL in Context

Current international models of disability consider the multiple factors that influence daily life and the ability to perform necessary life tasks (

13). These models recognize the importance of the physical and social settings in which an individual lives, and how these factors come together to support or limit task performance and participation as a member of society. Others with whom an individual regularly spends time constitute that individual’s social nucleus, providing important support and social interaction and influencing activity choices and role requirements as well as the level of independence (

14,

15,

16). This nucleus typically includes friends, acquaintances, and members of the individual’s immediate and extended family.

It is within this social situation that the importance of self-care is most apparent, because meeting self-care needs is vital to success in meeting expectations for social interaction. Self-esteem, or the value accorded oneself, is determined by how well self-evaluation matches the values perceived as important in the social environment (

17). Self-esteem is influenced by social acceptance and by one’s success in achieving a desired social identity (

18,

19,

20,

21). Because the ability to perform self-care tasks contributes to both acceptance and identity, it can have a direct effect on self-esteem (

19,

22). Importantly, social factors, including social support, are important predictors of rehabilitation outcome as shown by studies of amputation (

23), stroke (

24,

25), serious burn injury (

26), spinal cord injury (

20), hip fracture (

27).

Typically, self-care activities are taken for granted by the person and society unless difficulties are encountered. Limitations in self-care tasks and dependency on others for their completion serve to diminish an individual’s self-concept and can lead to decreased morale and depression (

28). A study of elderly patients found that a relationship existed between self-concept and functional independence, and that people who were dependent in ADL scored lower in measures of self-concept (

19).

Research has shown a clear relationship among self-concept, morale, and level of functional independence. For example, Chang and MacKenzie found that self-esteem was a consistent and significant predictor of functional ability at various intervals following stroke (

20). Chemerinski et al. found that improvements in ADL performance were associated with remission of poststroke depression (

21). These studies and others (

29) indicate that an important goal of rehabilitation should be to help patients learn to take control of decisions about daily living, since this may contribute positively to their sense of efficacy, morale, and overall sense of well-being. More important, it may also increase life expectancy, since loss of hope and feelings of helplessness during early rehabilitation phases have been shown to be associated with shorter survival rates following stroke (

30).

Within living settings, the presence of an individual with needs for care-giving affects the entire family or social group (

31,

32). When a member of the family can no longer perform expected activities, the daily routine may be upset, creating stress, diminished psychological well-being, and conflict (

33). Family members must adjust their expectations of the individual who is disabled as well as adjust to changes in family routines and activities (

34).

Family caregivers are important to the well-being of persons with disability and chronic illness (

35). Over time families experience stages and time periods, each with characteristic issues. Important concerns related to self-care and care-giving needs must be considered in light of these stages, with recognition that needs change over time. The most significant change affecting caregiving is the number of family members who are available to provide support as a family life cycle matures.

Necessary adjustments made by families or caretakers confronted with rehabilitation challenges often include a reassignment of homemaking tasks or changes in priorities and may impose additional financial or social burdens due to the need to hire outside assistance or rely on volunteers (

36). Studies have shown that levels of depression and anxiety, as well as somatic complaints, are more prevalent among caretakers and family members of disabled people living in the home environment than those typically found among members of the general population (

33,

34). Yeung et al. found that self-confidence in Chinese family carers was an important factor in psychosocial well-being (

32). Caregiver burden, a term given to the general strain, isolation, disappointment, and emotional demands of caring for a member of the household with a disability, seems to increase in proportion with ADL needs (

37,

38,

39). A study of families involved in caring for survivors of stroke found that family adaptation after 1 year was related to family stresses and demands, family resources, and family perceptions. In particular, family functioning was poorer when the patient developed psychological morbidity, when the patient was less satisfied with the recovery, and when the health burden of the stroke was greater (

40). In recognition of the increasing importance of the role of household caregivers, interventional strategies, including counseling, education and training, and social support, have been reported. Recent meta-analyses have indicated that such interventions are effective in improving well-being and mental health and reducing the “burden” of care among caregivers (

41,

42).

During the rehabilitation process, the family can have a considerable influence on functional outcome (

43). A stable and supportive family unit can be of great assistance, whereas families that are functioning poorly can impede rehabilitation. In some cases, poor outcomes can be traced to a lack of family involvement in the rehabilitation process (

44). In other cases, too much support can encourage dependency (

41). This indicates that the family should be involved in all aspects of rehabilitation, including evaluation and the setting of rehabilitation goals and treatment strategies before and after discharge (

45).

A primary source of adjustment difficulties for people with physical disabilities comes from societal treatment of them as socially inferior (

46). The common belief that strength, independence, and appearance are important aspects of self-worth is very damaging to people with disabilities. Interaction within a social group often depends on the ability to perform at the group’s expected level; otherwise, the person will not be included as a significant group member (

18).

Self-care tasks are not publicly valued in the same manner as gainful employment (

47,

48). Ironically, they assume importance principally when one’s inability to perform them leads to perceived disadvantage or social stigma (

49). Self-reliance in ADL helps to refute the idea that a person with a disability may be a financial or social burden to society. It is important to realize that social participation and quality of life are often the ultimate goals of patients, and this endpoint should influence shared goal setting. Physical health is an enabler of well-being, and the capacity to accomplish self-care represents the beginning set of tasks necessary for participation. As noted by Hogan and Orme, ambulation and self-care mastery alone are insufficient for attaining desired goals related to social participation (

50). A research synthesis reported by Bays concluded that independence with ADL, and social support were key variables in the quality of life experienced by survivors of stroke (

51). Lund et al. determined that social participation in various activities of life, including self-care, contributed to perceived quality of life in survivors of spinal cord injury (

52). Cardol et al. (

53) asserted that ethical approaches to planning and implementing care in rehabilitation should place greater emphasis on the autonomy of the individual. This is exemplified by an attentive attitude, opportunities for informed choices by the patient, and consideration for each patient’s preferences, needs, and social contexts (

53). In some cases, active participation in goal setting by persons receiving rehabilitation may require special efforts to overcome lack of familiarity, perceived indifference, and other barriers to involvement (

54).

Self-care and Functional Performance

Traditionally, intervention for people who have difficulty performing self-care tasks has begun with training in the acute care or rehabilitation environment. Typically, such intervention includes instruction in procedures to regain dressing,

grooming, hygiene, and food preparation and eating skills. In pursuit of these goals, rehabilitation sessions have been conducted within the patient’s hospital room or in simulated ADL settings within the facility. Intervention strategies involve teaching the individual functional skills or the use of assistive technologies so that compensatory strategies can be performed in the postdischarge environment.

Unfortunately, as suggested earlier, ADL training in a rehabilitation facility does not guarantee skill generalization to the discharge location. Patients may perform well in a rehabilitation facility, but skills may not always transfer to the individual’s pre-admission or discharge living setting. Environmental and psychosocial factors that directly influence task performance may be too varied between settings for the person receiving rehabilitation to generalize the learned skills (

55). In addition, the individual may become dependent on the staff for self-care performance (

56) or lack the opportunity to practice new skills on a regular basis. Consequently, performance following discharge may reflect a lack of confidence or motivation.

Collaboratively Planning Self-care and ADL Goals

Current standards in rehabilitation require the involvement of the person receiving care as well as family members or caregivers, as appropriate in planning intervention (

60). Controlled studies have shown that active collaboration in rehabilitation goal setting increases client satisfaction with care (

61).

When goals are set in collaboration with the individual receiving care, the motivation to learn and maintain a skill is better than if rehabilitation professionals or caregivers determine the goals. It also appears that agreement on goals may influence functional outcomes by establishing clearer and more realistic goals (

62). Each self-care behavior should be evaluated to see if the individual is motivated to learn and maintain it. Some studies have shown differences in the extent to which professionals and persons receiving care have congruent views regarding rehabilitation goals (

63) but generally support the value of client participation in decision-making about care (

61,

64,

65,

66,

67). This underscores the need for close collaboration between providers and recipients of care when planning intervention.

One of the first options the professional and person receiving rehabilitation should explore concerning the performance of any self-care task is whether the task is necessary or desired. The individual may choose not to perform some self-care tasks that were done before his or her illness. For example, a woman with hemiplegia who formerly rolled her hair on rollers on a daily basis may decide to have it cut in an easierto-manage style rather than learn to use rollers with one hand. This type of decision should be based on individual preferences. Similarly, changes in societal styles and norms may also influence self-care goals, since greater diversity in clothing, hairstyle, and general appearance make it less likely that deviations from the norm will stand out.

In some instances, training procedures can be used to regain a desired skill. Following a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), for example, the therapist may be able to retrain the person to perform the task as it was performed before the CVA if there is sufficient return of voluntary movement. In some instances, the individual may no longer have the perceptual or physical capability to perform a task as before. However, he or she may be able to learn to accomplish the task using different movement patterns or with different body parts.

Environmental changes represent an additional array of intervention options that can be explored by the individual and his or her rehabilitation team as a means of gaining independence in self-care. In some instances, simply rearranging the physical environment may allow the disabled person to perform tasks independently. For example, moving dishes to lower shelves so that the patient can reach them from a wheelchair would represent a modification of the environment requiring only simple rearrangement. Structural changes in the physical environment also may be necessary. These can include major changes such as the architectural modification of rooms to accommodate wheelchair movement or less extensive improvements such as replacing round doorknobs with lever handles for a person who has weak grasp or installing bathroom rails and grab bars for persons with unsteady gait or balance difficulties.

The idea of universal design, which describes key principles for making environments, facilities, and objects useable for people regardless of their physical attributes or limitations, should have a positive impact on reducing barriers to activity and participation in the years ahead (

68). This emerging environmental movement is broader than previous concepts of environmental accessibility (as described in the Americans with Disabilities Act and other legislation), yet highly relevant to rehabilitation and disability. Universal design emphasizes creating environments and objects that are simple and intuitive and that enable equitable and flexible use, have perceptible forms of information, require low physical effort, have tolerance for error, and have sizes and shapes appropriate for approach and use.

Assistive technology devices (ATDs) can be used to aid in the satisfactory performance of a desired task. These devices can range from simple, inexpensive articles, such as bathtub seats, to the use of expensive equipment such as computers for environmental control and communication (

69). Many labor-saving devices are now widely available in catalogs and retail outlets catering to the general population. A line of fashionable apparel

designed for easy dressing and maintenance is now available for persons with limitations in range of motion. The rehabilitation professional’s role is to inform the patient of the existence and cost of these devices and to train the individual and caregiver in their use and maintenance.

Assistance from other people for the partial or total completion of a desired task is another option available to the individual receiving care (

70). Assistance may come from spouses, friends, or paid PCAs. The role of the professional in this case must be to instruct the individual and/or the care attendant on optimal approaches to working together for the completion of identified self-care tasks (

71).

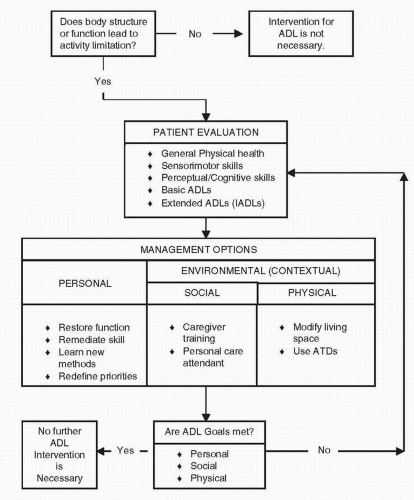

Figure 9-1 provides a decision chart that describes the process of goal setting summarized in this section.

Collectively, the personal and environmental intervention options described in this section form the basis for collaborative decision-making and treatment planning. It should be borne in mind that neither diagnosis alone nor the extent of impairment can serve as an adequate basis for planning self-care intervention. Together, the rehabilitation team and the individual receiving care must determine those approaches that represent the most realistic and achievable goals based on the abilities, values, and personal social circumstances of the recipient of care (

61). Only in this way will optimal results be achieved after discharge.