I. Forearm fractures are a common injury often occurring from a fall or a direct blow. Twenty six percent of fractures involving both bones of the forearm occur in children younger than 15 years of age.

The treatment for these injuries depends on a number of factors. These include the patient’s age, bone quality, physiologic health, specific injury pattern, associated injuries, and physical demands. There are four main types of forearm fractures: (a) an isolated fracture of the radius or ulna, (b) fracture of the radius with a distal radial ulnar joint (DRUJ) dislocation (Galeazzi fracture), (c) fracture of the ulna with a radial head dislocation (Monteggia fracture), and (d) a both bone forearm fracture of the radius and ulna. The treatment of most fractures of the forearm, except some isolated ulnar shaft fractures, is operative.

II. Anatomy—The forearm is complex with two mobile parallel bones, which essentially function as a joint with a proximal and distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ). There are several muscles that originate in the forearm and insert on the hand and provide hand function. Thus, it is of paramount importance following a forearm fractures to restore rotation of the forearm, range of motion of the wrist and elbow, and grip strength.

A. Bones

1. Radius—Proximally the radius has a radial notch for articulation with the ulna, and distally there is a notch for articulation as well. There is a tuberosity in the proximal portion of the radius for insertion of the biceps. The radius has a bow, which must be restored during fracture treatment. Every 5° loss of radial bow results in a 15° loss of pronation and supination. After open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of a both bone forearm fracture, the recovery of grip strength and forearm motion correlates with restoration of the normal radial bow.

2. Ulna

B. Interosseous Membrane—The interosseous membrane is between the two bones and is very important in assisting with forearm function as well. The interosseous membrane is of key importance for forearm stability. The interosseous membrane can be considered as proximal, middle, and distal thirds with the middle third being the strongest and most significant contributor to longitudinal stability of the forearm.

C. Muscles

1. Volar

• The mobile wad consists of the brachioradialis, the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) The radial nerve provides innervation.

• The flexor pronator group is arranged in three layers. The median and ulnar nerves provide innervation.

(a) The superficial layer—The superficial layer has four muscles arising from the medial humeral epicondyle spanning out across the forearm. It is easy to remember these in their orientation if you place your hand at the medial epicondyle with the palm on the anterior surface of the forearm. The thumb represents a pronator teres. The index finger represents the flex carpi radialis, the middle finger represents the palmaris longus (which is absent in approximately 10% of the population), and the ring finger represents the flexor carpi ulnaris.

(b) The middle layer is the flexor digitorum superficialis.

(c) The deep layer is the flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicus longus, and pronator quadratus.

2. Dorsal

• Superficial—The superficial extensor muscles fan out from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. From the ulnar side to the radial side, they are the:

(a) anconeus

(b) extensor carpi ulnaris

(c) extensor digiti minimi

(d) extensor digitorum communis

• Deep

(a) The abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis provide motor function to the thumb and cross the forearm from the ulnar to the radial side in an oblique manner.

(b) The remaining deep muscles are the supinator and the extensor indicis.

D. Nerves

1. Radial nerve

• The radial nerve has a superficial sensory branch along the lateral aspect of the forearm. It runs under the brachioradialis muscle.

• The anterior branch of the radial nerve supplies the mobile wad muscles (brachioradialis, ECRL, ECRB).

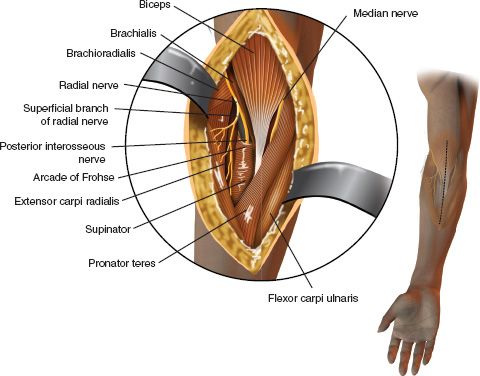

• The deep branch is the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) (Fig. 22-1). The PIN passes between the two heads of the supinator and emerges distally over the origin of the abductor pollicis longus lying along the interosseous membrane. In 25% of patients, the PIN is directly on bone near the biceps tuberosity.

(a) To protect the nerve, do not place retractors on the posterior surface of the proximal radius.

(b) With proximal exposure of the forearm, supinate the forearm to protect the nerve.

FIGURE 22-1 Course of the posterior interosseous nerve in the proximal forearm.

2. Median nerve—The median nerve enters the forearm and antecubital fossa region and splits the pronator teres running between the flexor digitorum superficialis and the flexor digitorum profundus.

3. Ulnar nerve—The ulnar nerve travels under the flexor carpi ulnaris and lies on the flexor digitorum profundus in the forearm. The ulnar artery lies on the radial side of the nerve.

E. Arteries—The radial and ulnar arteries are branches of the brachial artery.

1. Radial artery—Proximally, the radial artery lies just medial to the biceps tendon and angles across the arm lying on the supinator, the pronator teres and the origin of the flexor pollicis longus. The radial artery is palpable on the distal anterior radius.

2. Ulnar artery—The ulnar artery runs between the flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis; distally, it runs between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum superficialis.

A. Volar (Henry) Approach—This extensile approach uses an internervous plane between the radial nerve and the median nerve. The muscular interval is between the brachioradialis and the pronator teres/flexor carpal radialis.

B. Dorsal (Thompson) Approach—The internervous plane is between the radial nerve and the PIN. The dorsal approach of Thompson utilizes the interval between the extensor carpal radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis/extensor pollicis longus.

C. Approach to the Ulna—The ulnar is approached between the extensor carpi ulnaris and the flexor carpi ulnaris right along the bone. The internervous plane is between the PIN and the ulnar nerve.

D. Cross-Sectional Anatomy of the Forearm (Fig. 22-2).

IV. Physical Evaluation—The patient with a forearm fracture often has obvious signs and symptoms of a fracture, with deformity and crepitus. The physical examination should include the elbow and wrist. Close evaluation of the soft tissue is necessary to assess for any evidence of open fracture, soft-tissue injury, and injury of the median, radial, and ulnar nerves. It is also important to evaluate the patient for compartment syndrome (discussed later in this chapter).

V. Radiographic Evaluation—Radiographic evaluation of the forearm includes an anteroposterior (AP) and lateral view of the forearm as well as AP, lateral and oblique views of the elbow and wrist. If there is a fracture of the radial head, a special radial head radiographic view may be obtained as well. It is not necessary to include computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for routine forearm fractures. Magnetic resonance imaging may provide further information regarding ligamentous disruption and joint involvement.

VI. Specific Injury Patterns and Treatments

A. Radial Shaft Fractures

1. Nondisplaced radial shaft fractures—Nondisplaced radial shaft fractures may be treated in a cast until the fractures is healed. Initially a long-arm cast is used until the fracture becomes “sticky” and then a short-arm cast may be used.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree