I. Anatomy

A. Ring Structure of Three Bones—Two innominate bones and the sacrum. Innominate bone is formed by fusion of three ossification centers—ilium, ischium, and pubis.

B. Sacroiliac (SI) Joint is Comprised of Two Parts:

1. Articular portion—Located anteriorly. Not a true synovial joint. Articular cartilage on sacral side. Fibrous cartilage on iliac side.

2. Fibrous or ligamentous portion—Located posteriorly.

C. Ligaments

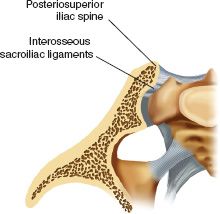

1. Posterior SI ligaments—Considered to be the strongest ligaments in the body (Fig. 15-1).

• Short component—Oblique fibers that run from the posterior ridge of the sacrum to the posterosuperior and posteroinferior iliac spines.

• Long component—Longitudinal fibers that run from the lateral sacrum to the posterosuperior iliac spines; merges with sacrotuberous ligament.

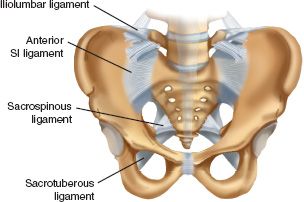

2. Anterior SI ligaments—Runs from ilium across sacrum (Fig. 15-2).

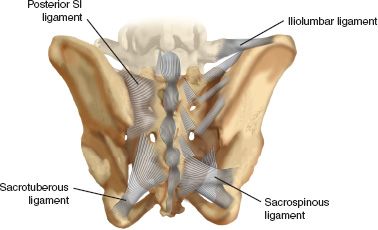

3. Sacrotuberous ligaments—Strong band running from posterolateral sacrum and dorsal aspect of the posterior iliac spine to the ischial tuberosity. Along with the posterior SI ligaments, these ligaments maintain vertical stability of the pelvis (Fig. 15-3).

4. Sacrospinous ligament—Runs from the lateral edge of the sacrum and coccyx to the sacrotuberous ligament and inserts on the ischial spine. Triangular in shape. Separates the greater and lesser sciatic notches.

5. Iliolumbar ligaments—Run from L4 and L5 transverse processes to the posterior iliac crest stabilizing the spine to pelvis.

6. Lumbosacral ligaments—Run from L5 transverse process to the sacral ala.

D. Pubic Symphysis

1. Hyaline cartilage on medial (articular) aspect of pubis.

2. Surrounded by fibrocartilage and a thick band of fibrous tissue.

E. The iliopectineal line (pelvic brim) separates the false pelvis (above) from the true pelvis (below).

1. False pelvis—Iliac wings and sacral ala; surrounds the intra-abdominal contents; contains iliacus muscle.

2. True pelvis—Pubis, ischium and small portion of ilium; contains floor of true pelvis (coccyx, coccygeal and levator ani muscles, urethra, rectum, vagina) and obturator internus muscle.

F. Neural Structures

1. Sciatic nerve—Formed by roots from the lumbosacral plexus (L4, L5, S1, S2, S3). Exits the pelvis deep to the piriformis muscle.

2. Lumbosacral trunk—Formed from anterior rami of L4 and L5, crosses the anterior sacral ala and SI joint. Fractures of the sacral ala or dislocations of the SI joint are most likely to injure the lumbosacral trunk.

FIGURE 15-1 Cross section through the sacroiliac joint, showing the direction of the interosseous sacroiliac ligaments.

FIGURE 15-2 Anterior view of the pelvis showing the anterior SI ligament and the sacrospinous ligaments that is a strong triangular ligament anterior to the sacrotuberous ligament.

FIGURE 15-3 Posterior view of the pelvis showing the posterior sacroiliac ligament, iliolumbar ligament, sacrospinous ligament and the sacrotuberous ligament.

3. L5 nerve root—Exits below L5 transverse process and crosses the sacral ala 2 cm medial to the SI joint. May be injured during anterior approach to the SI joint.

G. Vascular Structures

1. Median sacral artery—Continuation of the aorta, which travels along the vertebral column. Small caliber and not of major significance.

2. Superior rectal artery (hemorrhoidal artery)—Continuation of the superior mesenteric artery. Rarely involved in pelvic trauma.

3. Common iliac artery—Divides into internal and external iliac arteries.

4. Internal iliac artery (hypogastric artery)—Major importance in pelvic trauma.

• Anterior division

(a) Inferior gluteal artery—Exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch inferior to the piriformis (between piriformis and superior gamelli). Supplies the gluteus maximus.

(b) Internal pudendal artery—Crosses the ischial spine and exits through the lesser sciatic notch. Commonly injured in pelvic fractures.

(c) Obturator artery—May be disrupted in pubic rami fractures.

• Superior vesical artery—A branch of the obturator artery that supplies the bladder.

(d) Inferior vesical.

(e) Middle rectal artery.

• Posterior division

(a) More prone to damage due to posterior pelvic displacement.

(b) Superior gluteal artery—Largest branch of the internal iliac artery. Courses across the SI joint, and exits through the greater sciatic notch superior to the piriformis. Supplies gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fascia lata muscles. Most commonly injured vessel in pelvic fractures with posterior ring disruptions. Can be injured in obtaining a posterior iliac crest bone graft if you stray inferiorly. Can also be injured when passing a gigli saw through the sciatic notch during a pediatric innominate osteotomy.

(d) Lateral sacral artery.

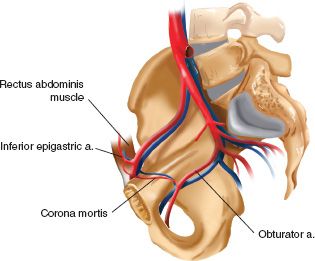

5. Corona mortis (Fig. 15-4)

• Common anastomosis between the obturator and external iliac systems. Incidence: venous anastomosis (70%), arterial anastomosis (34%), venous and arterial anastomosis (20%).

• Crosses the superior pubic ramus in a vertical orientation at an average of 6.2 cm (range, 3 to 9 cm) from the pubic symphysis.

• If accidentally cut, the vessels may retract inferiorly into the obturator foramen and cause serious bleeding.

6. Pelvic veins—Massive venous plexus that drain into the internal iliac vein. Major source of hemorrhage in most pelvic fractures.

H. Urethra

1. Anatomy

• Male urethra has three portions—Prostatic, membranous, and bulbous. Bulbous urethra is located inferior to the urogenital diaphragm; if ruptured retrograde urethrogram dye extravasates into the perineum.

FIGURE 15-4 Schematic drawing showing the arterial and venous anastomsis between the external iliac and obturator systems known as the corona mortis.

• Female urethra—Short, not rigidly fixed to pubis or pelvic floor, more mobile and less susceptible to injury from shear forces.

2. Urethral injuries—More common in males. Stricture is the most common complication seen in patients sustaining a urethral injury. Impotence may be present in 25% to 47% of patients with urethral rupture. Cause is uncertain but is probably due to damage to parasympathetic nerves (S2 to S4).

• Obtain retrograde urethrogram to rule out urethral injury prior to insertion of a Foley catheter if there is anterior pelvic disruption or any sign of urethral injury.

• Signs of urethral injury: (a) inability to void despite a full bladder, (b) blood at the urethral meatus (c) high-riding or abnormally mobile prostate, and (d) elevated bladder on IVP.

• Absence of meatal blood or a high-riding prostate does not rule out urethral injury.

• Passing a Foley may turn a small perforation into a large perforation.

I. Bladder

1. Anatomy

• Males—Bladder neck is attached to the pubis by puboprostatic ligaments and is contiguous with the prostate.

• Females—Bladder lies on the pubococcygeal portion of levator ani muscles.

• Superior and upper posterior portion of the bladder are covered by peritoneum.

• Remainder of the bladder is extraperitoneal and covered with loose areolar tissue. Space of Retzius is located anteriorly.

2. Bladder injuries

• May be caused by bony spicules from pubic rami fractures, blunt force injuries causing rupture, or shearing injuries.

• Intraperitoneal ruptures—Require operative repair.

• Extraperitoneal ruptures—Managed nonoperatively unless undergoing ex lap for other reasons or a bony spicule invading the bladder. Catheter drainage and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Cystogram prior to catheter removal to verify healing. About 87%, healed by 10 days. Virtually all healed by 3 weeks.

II. Evaluation

A. History

1. Mechanism of injury determines energy of injury and likelihood of associated injuries.

2. Low-energy injuries

• Occur in elderly osteoporotic patients as a result of a fall from standing height. Treatment: analgesia, weight bearing as tolerated.

• Stress fractures may occur without an identified fall. Bone scan is useful for diagnosis.

3. High-energy injuries

• Common mechanisms are motor vehicle accidents (MVA), motorcycle accidents, pedestrian versus MVA, or fall from height.

• Associated injuries are common.

• High incidence of hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock.

• Require emergent evaluation and treatment.

B. Physical Examination

1. First priority is to assess for other life-threatening injuries using Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols.

2. Bimanual compression and distraction of the iliac wings.

3. Manual leg traction can aid in determination of vertical instability.

4. Careful palpation of the posterior pelvis in awake patients can identify posterior pelvic injuries.

5. Rectal examination—High-riding prostate may indicate urethral tear. Positive guaiac test may indicate visceral injury. Palpation of the sacrum for irregularity.

6. Vaginal examination—Bleeding or lacerations indicating open fractures.

7. Perineal skin—Lacerations may indicate open fracture. May be caused by hyperabduction of the leg.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree