52 Fibromyalgia

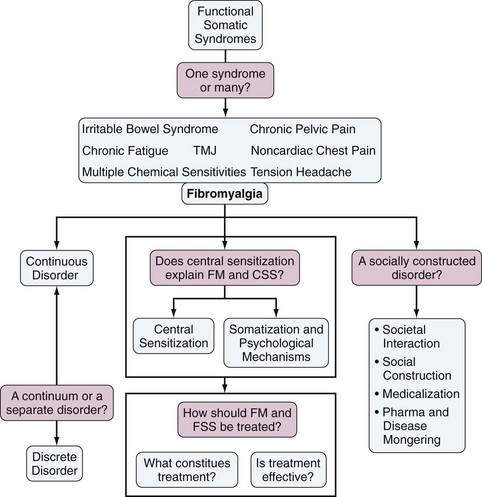

Fibromyalgia is a controversial disorder.1 Certain aspects of the controversies surrounding fibromyalgia reflect scientific disagreements about categorization, pathophysiology, and treatment (Figure 52-1). But another important reason for controversy is that the diagnosis carries with it profound societal consequences. Whether fibromyalgia “exists” or is “real” or should be valued matters a great deal to patients, payers, pension systems, researchers, professional and patient organizations, and pharmaceutical companies.2

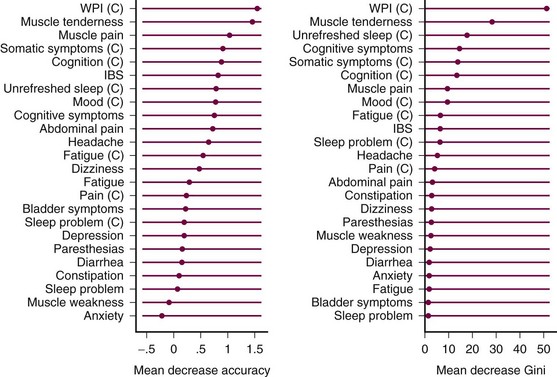

Fibromyalgia is a clinical syndrome that is defined by the presence of generalized pain, fatigue, unrefreshed sleep, multiple somatic symptoms, cognitive problems, and other symptoms, often including depression. Symptoms important to the fibromyalgia case definition are shown in Figure 52-2 in order of their importance.3 The 2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia require the presence of widespread pain and multiple symptoms (Table 52-1).3 The more restrictive ACR 1990 classification criteria require the presence of widespread pain plus the presence of tenderness on palpation in at least 11 of 18 specified “tender point” sites.4 Fibromyalgia can be diagnosed in the presence of other medical conditions and is never a diagnosis of exclusion. However, concomitant disorders associated with musculoskeletal pain and fatigue will always need to be identified.

Figure 52-2 Symptoms that differentiate patients who satisfy American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria from other rheumatic disease patients with noninflammatory rheumatic pain disorders sorted by strength of association.3 The two figures represent different measures of association. Higher scores mean stronger associations. (C), categorical variable; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; WPI, Widespread Pain Index.

Table 52-1 American College of Rheumatology 2010 Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia3

| Criteria |

| A patient satisfies diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia if the following 3 conditions are met: |

| Ascertainment |

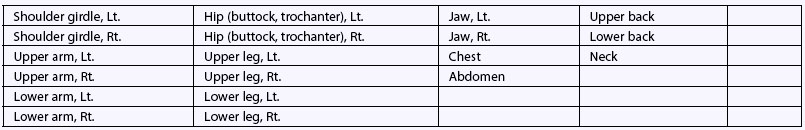

1. WPI: Note the number areas in which the patient has had pain over the past week. In how many areas has the patient had pain? Score will be between 0 and 19. For the each of the three symptoms above, indicate the level of severity over the past week using the following scale: Considering somatic symptoms* in general, indicate whether the patient has: The Symptom Severity Score is the sum of the severity of the three symptoms (fatigue, waking unrefreshed, cognitive symptoms) plus the extent (severity) of somatic symptoms in general. The final score is between 0 and 12. |

* For reference purposes, here is a list of somatic symptoms that might be considered: muscle pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue/tiredness, thinking or remembering problem, muscle weakness, headache, pain/cramps in abdomen, numbness/tingling, dizziness, insomnia, depression, constipation, pain in upper abdomen, nausea, nervousness, chest pain, blurred vision, fever, diarrhea, dry mouth, itching, wheezing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, hives/welts, ringing in ears, vomiting, heartburn, oral ulcers, loss/change in taste, seizures, dry eyes, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, rash, sun sensitivity, hearing difficulties, easy bruising, hair loss, frequent urination, painful urination, and bladder spasms.

The Fibromyalgia Construct

One Syndrome or One of Many?

The central features of fibromyalgia that were noted earlier are also found in illnesses such as chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, headache syndromes, and multiple chemical sensitivities, among many others (see Figure 52-1).5 Taken together, these syndromes have been called functional somatic syndromes (FSS).6 Because the symptom content of the syndromes is similar, as are the treatments and the demographic characteristics of patients who have the disorders, it has been suggested by many that a single diagnostic term, rather than individual syndrome names, should be used for diagnosis. These suggestions derive mostly from the psychiatric literature.7–9 Terms suggested include FSS and bodily pain disorder.9 However, if fibromyalgia is just a name given to the disorder primarily by rheumatologists, but does not differ essentially from other somatic syndromes, then fibromyalgia does not exist as a separate syndrome. Fibromyalgia versus FSS creates a series of problems. FSS connotes a strong psychologic component, which is undesirable to patients, pharmaceutical companies, and medical researchers. In addition, there is the logical inconsistency in which regulatory authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approve treatments for the select fibromyalgia indication, when fibromyalgia is not different from other FSS. The FDA mandate strengthens the position of fibromyalgia as a “separate” disease, although there is little evidence that it is such an entity.7,10

A Separate Syndrome or Part of a Continuum?

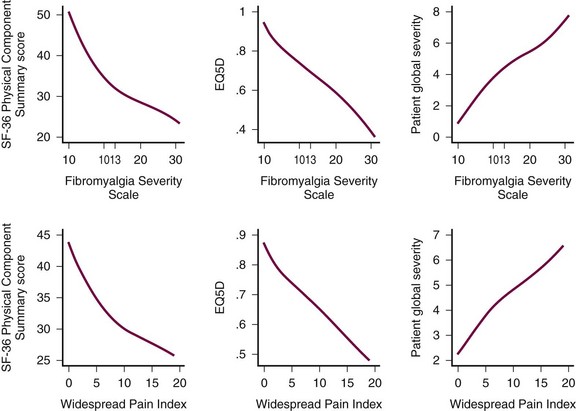

Fibromyalgia is properly considered to lie “at the extreme end of the spectrum of polysymptomatic distress.”11 Fibromyalgia diagnosis depends on splitting the distress continuum, placing on one side of the divide those with fibromyalgia and on the other side all other persons. Polysymptomatic distress refers to problems in many symptom areas—pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, functional impairment, psychologic status, and so on. Because symptoms are correlated, persons with high levels of one symptom will tend to have high levels of other symptoms. As an aggregate concept, polysymptomatic distress cannot be measured directly but can be approximated with the use of surrogate variables. One such surrogate measure of polysymptomatic distress is the fibromyalgia symptom scale—also called the fibromyalgianess scale.12 This scale represents the summation of the Widespread Pain Index (the number of body sites reported as painful) and characteristic fibromyalgia symptoms used in the ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria.3 In patients with various rheumatic diseases followed in the U.S. National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases,13 the upper part of Figure 52-3 shows the relation between the scale and the Short Form-36 (SF-36) Physical Component Summary (PCS) score, the EQ5D Quality of Life score, and the patient’s estimate of global severity. A value of 13 on the fibromyalgianess scale best divides fibromyalgia-positive and fibromyagia-negative patients.14 It can also be seen that the Widespread Pain Index alone is similarly associated with these three measures of illness severity (see Figure 52-3, lower part). About 2% to 4% of the adult population meets criteria for fibromyalgia. One can sense in the figure the distribution of polysymptomatic distress and its correlation with quality of life. Note that polysymptomatic distress is a quantity that exists in all persons, not just in those with fibromyalgia, though it is greater in those with fibromyalgia.

The higher the score on the polysymptomatic distress scale and the Widespread Pain Index, the more likely we are to find evidence of social disadvantage such as lower income, less education, and childhood mistreatment, and we will also find more psychologic distress and abnormality; it appears that these factors play a role in the development of fibromyalgia-like symptoms and symptom intensification.14 Fibromyalgianess differs from other measures of polysymptomatic distress by the centrality of musculoskeletal pain because nonarticular musculoskeletal pain is a central component of the scale.

To define fibromyalgia by criteria, we must, in effect, draw a line on the distress continuum and say that those beyond this line have fibromyalgia and those before it do not. In the ACR 2010 criteria (see Table 52-1),3 the cut point is identified by the extent of widespread pain and fibromyalgia symptoms. In the 1990 criteria (Table 52-2), the cut point is represented by a combination of tender points and widespread pain. Both cut points, though aided by data analyses, are determined by committees. There is nothing intrinsic in the polysymptomatic distress scale that tells us where the dividing point is. But in the general population a PCS score of 50 represents the population mean, with each standard deviation representing 10 units. At a fibromyalgianess score of 13, patients designated as fibromyalgia have a PCS score about 2 standard deviations below the mean (see Figure 52-3, upper left). Thus fibromyalgia diagnosis identifies persons with substantially reduced quality of life—those at the “extreme end of the spectrum of polysymptomatic distress.”11

Table 52-2 1990 American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia*

* For classification purposes, patients will be said to have fibromyalgia if both criteria are satisfied. Widespread pain must have been present for at least 3 months. The presence of a second clinical disorder does not exclude the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.

From Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee, Arthritis Rheum 33(2):160–172, 1990.

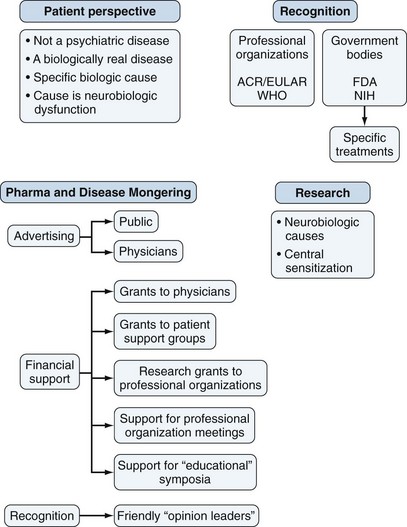

Social Construction and Medicalization

Many physicians doubt the existence of fibromyalgia as a separate entity, considering instead that it is a primarily a psychologic illness—not a “real disease”11,15–17 (see Figures 52-1 and 52-4). Epidemiologic and clinical studies give no support to the idea that fibromyalgia is a distinct entity18–20; instead, they support the contrary idea that fibromyalgia represents the end of a spectrum of polysymptomatic distress.

Illnesses exist within societies, and their existence and phenotype are often a function of the degree of acceptance of the disorder.21 The idea and consequences of fibromyalgia as a socially constructed, medicalized disorder has been discussed at length.2 An illness may be considered to be socially constructed when it is at least in large part the consequence of societal factors22 that result in “the creation (or construction) of new medical categories with the subsequent expansion of medical jurisdiction.”23 Medicalization is “a process in which nonmedical problems become defined and treated as medical problems, usually in terms of illness and disorders [and are] described using medical language, understood through the adoption of a medical framework, or treated with a medical intervention.”24

Ivan Illich’s 1976 description of medicalization in society set out some markers that are germane to understanding fibromyalgia and opposition to it.25 Illich wrote: “In a morbid society the belief prevails that defined and diagnosed ill-health is infinitely preferable to any other form of negative label or to no label at all” and that “people want to hear the lie that physical illness relieves them of social and political responsibilities.” He called these people “innocent victim[s] of biological mechanisms. … ” In addition, he said diagnosed “ill-health” provides access to disability programs and access to additional health care.25 Data from research about the neurobiologic investigations of pain mechanisms are offered as strong support that persons with fibromyalgia are “innocent victim[s] of biological mechanisms …”26

Given the social construction of fibromyalgia, medicalization is driven primarily by three components (see Figure 52-4). The first is the primary need for patients with fibromyalgia and other FSS for legitimization: Others need to understand that the problem is real and serious, and not primarily a psychosomatic illness.2 The diagnosis of a “valid” fibromyalgia provides entry to medical insurance and treatment and is grounds for work disability and pension. Extensive networks of patient organizations throughout the world work toward this purpose.2 The second pillar of medicalization in fibromyalgia is the pharmaceutical industry.27 Direct-to-patient advertising is ubiquitous. Often deceptive, it seeks to expand the definition of fibromyalgia, entice persons with pain and fatigue into the diagnosis, and strongly promote its treatments as effective.27 Industry financially supports patient and professional organization, medical education and symposia,2,28 and advertising in professional and lay journals. Virtually all major authors of fibromyalgia studies have received pharmaceutical company support. The influence of drug companies has increased dramatically in the past two decades to the extent that “ … companies are having an increasing impact on the boundaries of the normal and the pathological, becoming active agents of social control.23

Although “medicalization is now more driven by commercial and market interests than by professional claims-makers,”23 physicians and professional organizations remain the importance sources of scientific support, and National Institutes of Health grants for fibromyalgia research have become common.

Historical Development

Attempts to characterize and diagnose fibromyalgia have gone through several changes in conceptualization. The earliest roots of the syndrome can be found in the nineteenth century perception of abnormal connective tissue and muscles. In various forms, this concept held sway until the late 1970s when a new emphasis on sleep disturbance and tender points led to proposed clinical criteria that included sleep disturbance and tenderness to palpation at 12 of 14 selected sites.29 In the early 1980s, most of the other fibromyalgia-associated symptoms were identified, and unofficial criteria were proposed that combined symptoms with tenderness.30 With the publication of the ACR criteria in 1990,4 the fibromyalgia case definition was reduced to generalized pain and the presence of multiple tender points. The 1990 criteria, supported by the imprimatur of the ACR, gave the syndrome official sanction. With the criteria publication, professional opposition to fibromyalgia solidified and has continued until the present.2,31–37 In 2010 the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria3 were published. These criteria expanded the case definition and criteria items to include widespread pain and multiple symptoms including fatigue, disturbed sleep, cognitive symptoms, and multiple somatic symptoms. Despite scientific data questioning the validity of fibromyalgia as a distinct entity, fibromyalgia has become a dominant paradigm, supported strongly by funding and influence of the pharmaceutical industry. At present there are currently several opposing views of fibromyalgia. One view holds that it is not distinct and is a part of FSS,7,9,10 with a functional symptom being defined as one that “after appropriate medical assessment, cannot be explained in terms of a conventionally defined medical disease.”7 The second view, and the dominant paradigm, supports the concept that fibromyalgia is a disorder of “ … aberrant central pain transmission … [in which] purely behavioral or psychologic factors are not primarily responsible for the pain and tenderness … ”38 A third view holds that fibromyalgia is the end of a spectrum of polysymptomatic distress and is not a distinct entity.2,11 Perhaps, not surprisingly, these views are not mutually exclusive.

Clinical Features

Fibromyalgia is characterized by high levels of pain, sleep disturbance, and fatigue combined with a general increase in medical symptoms (Table 52-3) including problems of memory or thinking and often psychologic distress.39

Table 52-3 Prevalence of Specific Symptoms among 2784 Patients with Fibromyalgia in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases

| Symptom | % |

|---|---|

| Sleep problems | 89.1 |

| Fatigue or tiredness | 88.6 |

| Muscle pain | 85.2 |

| Muscle weakness | 70.2 |

| Paresthesias | 67.6 |

| Cognitive problems | 66.3 |

| Headache | 64.7 |

| Dry mouth | 53.3 |

| Insomnia | 51.8 |

| Easy bruising | 49.1 |

| Dry eyes | 47.5 |

| Depression | 47.5 |

| Blurred vision | 47.0 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 46.3 |

| Heartburn | 44.4 |

| Itching | 44.3 |

| Dizziness | 42.1 |

| Constipation | 41.9 |

| Pain/cramps in the abdomen | 41.5 |

| Ringing in ears | 41.4 |

| Pain in upper abdomen | 40.3 |

| Nervousness | 39.7 |

| Nausea | 37.7 |

| Diarrhea | 33.6 |

| Shortness of breath | 32.3 |

| Hearing difficulties | 29.8 |

| Hair loss | 23.6 |

| Oral ulcers | 22.4 |

| Wheezing | 21.4 |

| Loss of appetite | 21.1 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 20.1 |

| Chest pain | 19.2 |

| Rash | 17.1 |

| Sun sensitivity | 16.7 |

| Loss/change of taste | 14.4 |

| Fever | 13.4 |

| Hives/welts | 9.3 |

| Vomiting | 9.1 |

| Seizures | 1.7 |

Individuals with the syndrome are unusually sensitive to digital pressure (tender points) in certain body areas. Clinically, fibromyalgia is often identified or suspected by the inexplicability and severity of symptoms and by their number. The most common defining symptom is that of generalized pain (“pain all over”), and pain all over, or widespread pain, is a requirement of the 1990 and 2010 criteria. The clinician may be surprised by the extent and severity of symptoms (see Table 52-3 and Figure 52-3) and surprised at unexpected emotional distress. Fibromyalgia has a quality of inexplicability and unexpectedness.

Fibromyalgia patients perform more poorly in formal cognitive testing than age-matched controls.40 In the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases in 2006, 66% of 2784 fibromyalgia patients complained of memory or thinking problems compared with 31% of 24,479 patients with other rheumatic conditions. The most common symptoms, found in more than two-thirds of patients, are sleep problems, fatigue, muscle pain, paresthesias, and cognitive problems (see Table 52-3). In addition, the prevalence of other important symptoms is as follows: headache, 65%; depression, 48%; and irritable bowel syndrome, 46% (see Table 52-3). A high count of symptoms is characteristic of fibromyalgia and is frequently a key item in the 2010 diagnostic criteria to diagnosis (see Figure 52-2). Fibromyalgia is also associated with increased reporting of comorbid conditions.41,42 The typical picture of fibromyalgia emphasizes certain symptoms (pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, cognitive problems) and an abundance of symptoms and comorbidities. Given the high levels of symptom variables and membership at the tail of the pain-distress continuum, it is not surprising that evidence of psychosocial disruption and high rates of lifetime psychiatric illness are found.43,44

Assessment and Diagnosis of a Patient with Fibromyalgia

Diagnosis and Diagnostic Criteria

A number of approaches to fibromyalgia diagnosis are available. To treat patients, recognition of the degree of pain, fatigue, and other symptoms is necessary, but a specific diagnostic term is not.2,11 Chronic pain syndrome, FSS, or fibromyalgia will all suffice for a diagnostic term in most settings. But in countries such as the United States, chronic pain syndrome or FSS often may not be sufficient for access to insurance reimbursement or pension systems. In addition, direct-to-patient advertising may influence diagnostic terminology and diagnosis toward fibromyalgia.

Today, two sets of valid criteria for fibromyalgia are used in most of the world, although country-specific criteria also exist.45 The approach to fibromyalgia diagnosis should differ according to the setting and the physician’s underlying beliefs about fibromyalgia acceptability. The 1990 ACR classification criteria (see Table 52-2)4 require the presence of widespread pain and the identification of pain on palpation at 11 or more of 18 tender points. Until 2010, with the publication of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria,3 the 1990 criteria was the only method for an official diagnosis. The 2010 diagnostic criteria are easier in some ways and more difficult in others. They are easier because they eliminate the tender point examination that may be difficult for some examiners. The 2010 criteria are more difficult because they require a thorough symptom evaluation. One advantage of the 2010 criteria is that the examiner/interviewer becomes much more familiar with the spectrum and degree of the patient’s problem. But for the criteria to work correctly, the interviewer must be comprehensive and thorough. The 2010 criteria provide two scales to evaluate the degree of polysymptomatic distress: the symptom severity scale and the fibromyalgianess scale, both of which are discussed earlier. The fibromyalgianess scale has the advantage that it is a continuous measure of polysymptomatic distress. It is suitable for use in all patients whether or not they satisfy fibromyalgia criteria now or have satisfied them in the past. The scale is also useful when the physician or examiner does not believe in the fibromyalgia concept because it does not require a criteria diagnosis to be useful. The ACR 2010 criteria have been modified by the authors so that self-report forms can be used.14 Although these self-report, form-based criteria can be useful for survey and clinical research, they have not been endorsed by the ACR and they should never be used for clinical diagnosis.

Primary, Secondary, and Secondary-Concomitant Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is sometimes divided into primary, secondary, and secondary-concomitant fibromyalgia. The term primary fibromyalgia is most often used when there is not another condition with symptoms that could explain fibromyalgia symptoms. This division between primary and secondary fibromyalgia is artificial, however. Back pain in older individuals when age-related radiographic changes are present might be considered secondary fibromyalgia, whereas the same symptoms in younger individuals might be considered primary fibromyalgia. The ACR 1990 criteria study4 showed no difference between primary and secondary fibromyalgia with regard to symptoms and diagnosis. The usefulness of primary fibromyalgia occurs in clinical trials, in which it is desirable to ensure those symptoms are not coming from another well-established illness. A fibromyalgia diagnosis implies understanding of issues such as pain, fatigue, sleep, and cognitive and emotional problems. When fibromyalgia is considered only in patients without other musculoskeletal conditions, the “benefit” of fibromyalgia diagnosis—its consideration of symptom issues and extent of pain—is lost. If fibromyalgia is to be diagnosed or considered, such consideration should be applied to all patients. As noted earlier, fibromyalgia is never a diagnosis of exclusion. When fibromyalgia is diagnosed in the presence of another condition, treatment is indicated for one or both disorders, as determined clinically.

Assessment of Fibromyalgia Severity

Self-Report Measures

The ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria provided a new measure of fibromyalgia severity, the Symptom Severity Score (see Table 52-1).3 Used in the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, this scale also functions as a measure of the severity of fibromyalgia symptoms and can be useful independently of the criteria. Another scale that is an effective measure is the fibromyalgianess scale.14,46 It is the sum of the two items used in the 2010 criteria, the Widespread Pain Index and the Symptom Severity Score. It is suitable for use in all patients, regardless of fibromyalgia status, thereby integrating fibromyalgianess and fibromyalgia symptoms into general patient care.

Symptom severity, physical function, and work status are the key status and outcome variables in fibromyalgia, as in other rheumatic disorders. Assessments that can be useful routinely to clinicians include measurements of pain, fatigue, physical function, sleep quality, anxiety, depression, and work status. At minimum, assessments should include visual analog scales (VAS) for pain and fatigue and a measure of functional status. Function can be assessed by one of the family of health assessment questionnaires including the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ),47 the Health Assessment Questionnaire–II (HAQ-II),48 and the Multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ).49 The HAQ is a 33-item questionnaire; the function scale of the HAQ-II and MDHAQ is a 10-item questionnaire. Simple scales for the assessment of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance also can be added. For simplicity and ease of administration, however, we recommend VAS assessments of pain and fatigue and either the HAQ-II or MDHAQ.

The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) is a widely used 21-item research assessment scale that addresses all of the key fibromyalgia variables and can be used in clinical care.50–52 The limitation of the FIQ is that it is suitable only for use in fibromyalgia patients, whereas the previously mentioned health assessment questionnaires are useful and have been used across the entire range of rheumatic disorders. In addition, the FIQ total scale has no simple interpretation.

Functional questionnaire results have reduced validity among fibromyalgia patients. Compared with patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, there was striking discordance between observed and questionnaire-reported activities in patients with fibromyalgia.53 This discordance limits slightly the usefulness of functional questionnaires and alters their interpretation: Results may represent perceived rather than actual functional difficulties.

Research Questionnaires

The Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trial committee has recommended research domains and questionnaires for fibromyalgia clinical trials.54 These domains include pain, fatigue, sleep, depression, physical function, quality of life and multidimensional function, patient’s global impression of change, tenderness, dyscognition, anxiety, and stiffness. The recommendations include use of the FIQ and the Medical Outcomes Scale SF-36.55,56 A recent study using observational data has shown that pain, HAQ, and fatigue explained more than 50% of fibromyalgia severity variance57 and that the main determinants of global severity and health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia are pain, function, and fatigue. On the basis of the ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria, criteria and survey assessments have been developed.14 The Symptom Intensity Scale, which combines the Widespread Pain Index and a VAS fatigue scale, is another self-report measure of fibromyalgia severity that is suitable for clinical and survey research.43

Physical Measures

With the exception of the performance of the tender point examination, the physical examination of a patient suspected to have fibromyalgia does not differ from the examination of any other rheumatic disease patient or pain patient. Measurement of pain threshold by the tender point examination is the only routinely useful physical measurement. Although helpful for diagnosis using the ACR 1990 classification criteria (see Table 52-2), the tender point count is poorly correlated with other fibromyalgia symptoms and with change in symptom severity among fibromyalgia patients.58 Patients may improve or worsen substantially without important differences in the tender point count.

How to Perform the Tender Point Examination

Fibromyalgia patients have a lower threshold for pain than do subjects without fibromyalgia.59 In the clinic, two methods exist by which tenderness can be elicited and measured60—digital palpation and dolorimetry.61 Tender point sites represent specific areas of muscle, tendon, and fat pads that are much more tender to palpation than surrounding sites. Sites selected as part of ACR 1990 criteria4 represent tender point sites that best discriminate between patients with and without fibromyalgia. To test for pain with digital palpation, the ACR 1990 criteria indicate that the examiner should press the tender point site with an approximate force of 4 kg. Usually the second and third fingers or the thumb is used for palpation, and a rolling motion is helpful in eliciting tenderness. The amount of force that the examiner uses is important because a large force would elicit pain in a subject without fibromyalgia, whereas a small force may miss tenderness. The amount of force that does not elicit tenderness in an individual without fibromyalgia (just below the pressure pain threshold) is the correct force to use. In practice, less force is required in smaller, thinner, less-muscled individuals. The pressure used by the examiner and the examiner’s interpretation of the patient’s response can influence results of palpation. The best and most appropriate way to perform the tender point count is to ask the patient if the palpation is painful, accepting only a “yes” as a positive reply, regardless of facial expression or body movement. Specifically, the frequently heard comment of patients to the digital examiner’s question regarding pain, “It’s tender,” is a negative rather than a positive response and should be followed by another question such as, “Yes, but is it painful?”

Epidemiology

Most of the information about fibromyalgia is based on sampling using the ACR 1990 criteria. Fibromyalgia is diagnosed more frequently in women (9 : 1 ratio) in clinical studies. However, in population-based studies the female-to-male ratio is lower. A recent five-country European study noted the female-to-male ratio to be about 1.7 : 1,62 though a U.S. study found a ratio of 6.8 : 163 and the ratio varies from high to low in other countries.62

Using ACR criteria, the prevalence of fibromyalgia in the adult general population is generally similar across the world. The prevalence of fibromyalgia in Wichita, Kansas, was 3.4% among women, 0.5% among men, and 2% overall63; among women in New York City, it was 3.7%.64 In Ontario, Canada, the estimated prevalence was 4.9% among women, 1.6% among men,65 and 3.3% overall. The prevalence of fibromyalgia in these studies increased with age until about age 70, after which it decreased slightly. Outside of North America, reports indicate the prevalence in five European countries was 4.7% and 2.9% according to different screening methods62; in studies in Bangladesh it was 5.3% to 7.5% in women and 0.2% to 1.4% in men66; in North Pakistan, it was 2.1% overall67; in Italy, it was 2.2%68; in Turkey, it was 3.6% for ages 20 to 6469; in Brazil, it was 2.5%70; and in Southwest Sweden, it was 1.3%.71

The prevalence of fibromyalgia in children in three studies was 1.2%,72 1.4%,73 and 6.2%.74 At a follow-up time of 1 year, approximately 25% of individuals meeting ACR criteria initially still satisfied the criteria.73,74 These data should not be interpreted as evidence of prognosis because some individuals not meeting criteria initially meet them at the 1-year follow-up. Instead, the data suggest that the concept of fibromyalgia in children may be dubious, particularly when dependent on tender point assessment. The prevalence of fibromyalgia is generally greater in clinical settings than in epidemiologic studies. It was noted to be 5.7% in general medical clinics75 and 2.1% in family practice settings.76 In rheumatology clinics, fibromyalgia prevalence was expectedly higher: 12%77 to 20%30 of new patients.

The ACR 2010 criteria should result in changes in the sex ratio because men have higher pain thresholds and are therefore less likely to be diagnosed as having fibromyalgia than women when the 1990 criteria are used. The proportion of men with fibromyalgia in the community in a large German population study was 40.3%.78 This study included criteria79 that used the Regional Pain Scale80 and measurement of fatigue. Diagnosis by this method yields results that are similar to survey modifications on the ACR 2010 preliminary criteria.14 The overall prevalence in the German study was 3.8%.78 Additional studies are necessary to determine the prevalence of fibromyalgia when the 2010 criteria are used.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

In the 30-year period following the establishment of the fibromyalgia case definition and criteria, there have been substantial advances in understanding mechanisms associated with fibromyalgia pain and other symptoms.81 Although most of the recent study data are robust, the interpretation of the data is often questionable and misleading. Because these research data form the basis of “scientific” support for fibromyalgia, the objections should be considered carefully and seriously. We outline some of the objection before providing the research data themselves.

1. Research data treat fibromyalgia as a disease associated with at least 11 tender points (ACR 1990 criteria definition), but it is exceedingly unlikely that the observed pathophysiologic abnormalities are confined to greater than or equal to 11 tender points because the body of clinical and epidemiologic evidence does not support a dichotomous condition. It seems likely that observed abnormalities are also found in nonfibromyalgia patients. Studies need to be performed to determine the distribution of the observed abnormalities in pain patients not satisfying the fibromyalgia classification criteria definition.

2. Almost all of the data linking the observed abnormalities to fibromyalgia are correlational, but they are often interpreted causally—a direction of causality that may be wrong. The causal path in fibromyalgia may be complex. All human processes and sensations are expressed biologically. It would be surprising not to find associations.

3. Even assuming causal associations, the explanatory power of these associations have not been described and may be weak. The noted associations do not necessarily predict development of fibromyalgia.

4. The pathogenetic associations attributed to fibromyalgia are noted in other disorders.82,83

5. The literature of fibromyalgia pathogenesis is filled with inadequate proofs because authors have drawn strong conclusions from limited correlative data.

6. Selection of patients and controls can be a problem. Specifically, patients may be too “good” and control subjects represent “healthy controls” rather than other pain patients. Healthy controls will always be different from patients with illnesses.

Genetic and Familial Factors

Compared with patients with rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia aggregated strongly in families: the odds ratio measuring the odds of fibromyalgia in a relative of a proband with fibromyalgia versus the odds of fibromyalgia in a relative of a proband with rheumatoid arthritis was 8.5.84 Genetic factors may predispose individuals to fibromyalgia.81 Patients with chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia have been found to have low gene expression for the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 and reduced levels of serum concentrations compared with controls. These findings might indicate a role for cytokines in the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia or as a sequel of chronic pain and its treatment.85 However, a study of 31,318 twins in the Swedish Twin Registry suggested that the co-occurrence of FSS in women can be best explained by affective and sensory components in common to all these syndromes, as well as by unique influences specific to each of them, suggesting a complex view of the multifactorial pathogenesis of these illnesses.83

Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors, which include reduced education, nonmarried status, lower household income, smoking, and obesity, have been identified in many studies. The chicken or egg question remains.82

There has been disagreement as to whether psychiatric abnormalities represent reactions to chronic pain or whether the symptoms of fibromyalgia are a reflection of psychiatric disturbance. Psychiatric disorders may interact with the neuroendocrine system as part of a stress reaction.44 The most common psychiatric conditions observed in patients with fibromyalgia include depression, dysthymia, panic disorder, and simple phobia.86 In the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases 64% of patients report prior depression, and 8% report mental illness. Fibromyalgia also occurs in patients without significant psychiatric problems, however. Some individuals with fibromyalgia satisfy the American Psychiatric Association criteria for somatoform disorders (DSM 307.80 and 307.89).87

Sleep Disturbance

Fibromyalgia patients often report unrefreshing and nonrestorative sleep.88 Electroencephalographic abnormalities initially were thought to play a major role in the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia, but it is now clear that such abnormalities are nonspecific findings. Sleep electroencephalographic studies show abnormalities of delta wave or stage 4 sleep by repeated alpha wave intrusion. Similar abnormalities are found in healthy individuals and in individuals with emotional stress, fever, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren’s syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree