31 Economic Burden of Rheumatic Diseases

The economic burden of musculoskeletal conditions is rapidly increasing in developing nations. Each discipline may use different tools to assess the burden of disease. Rheumatology health professionals may measure the impact of these conditions in terms of the discomfort and disability they cause and that these professionals may alleviate by providing health care. Psychologists may measure the impact of musculoskeletal conditions on the achievement of mental equipoise, or its opposite, mental discomfort. Economists take the measurements provided by other disciplines and turn them into monetary equivalents to describe the magnitude of the burden associated with musculoskeletal conditions. Thus economists are concerned with the monetary value of the resources used to produce health and with the return on the use of those resources in terms of reduced impacts of illness on pain and functioning. Cost of illness is an accounting of the resources spent in pursuit of health and of the residual amount of discomfort and disability left after those resources are spent1–3 (Table 31-1).

Table 31-1 Principal Methods to Assess Costs of Illness

| There are two principal methods to assess the costs of illness: (1) the human capital approach, developed by Dorothy Rice when she was at the Social Security Administration and later the National Center for Health Statistics,1,4 and (2) the willingness-to-pay approach.5 The two methods do not differ in the way that they assess the direct costs of medical care. For the indirect costs associated with loss of function and the intangible impacts of disease, the human capital approach uses the market value of the labor to reduce the impacts (e.g., by hiring a replacement worker). In a variant of the human capital approach called the “friction method,”3 the losses are estimated from the perspective of the employer and only last until the replacement worker is hired and then achieves the same productivity as the worker who left as a result of disease. At that point, an employer would be said to incur no additional costs from the onset of the prior incumbent’s disease. The willingness-to-pay approach values the loss of function as the amount the affected individual would pay to restore the function, which may be more, the same, or less than the amount it would take to replace the worker in the labor market. The human capital approach is no doubt more reliable in estimating the economic impact of the lost productivity of affected individuals because the cost of labor is well established in all advanced societies and, therefore, easy to estimate. The human capital approach, however, usually only enumerates the intangible impacts of disease (e.g., the burden associated with the experience of intense pain) but does not translate them into economic terms. The willingness-to-pay approach is theoretically capable of incorporating all of the costs of disease in those terms, although as a practical matter there are problems associated with attempting to do so.6 |

Economics is far more than a positive science, that is a discipline that observes how things are rather than seeking to change them, however. The normative part of the discipline has dual and sometimes competing goals. The first of these is ensuring that resources are allocated equitably (i.e., making sure that they are distributed fairly across individuals). The second is to make sure that they are used efficiently (i.e., as well as contemporary technology permits to produce goods).7 In health, resources would be distributed equitably if persons with similar levels of health received relatively equal access to health care services shown to reduce the burden of disease and which, based on a thorough knowledge of the treatment options, they chose for themselves. Similarly, in health, resources would be used efficiently if they produced the health outcomes people wanted while leaving the maximum amount to be used for other purposes, what economists refer to as “the opportunity cost” of those resources.

The evidence that the distribution of health care resources in the United States is inefficient has been increasing for several decades and comes from studies conducted within the United States8–10 and from those comparing the United States to other nations.11–13 The inequitable distribution, however, has also recently become a central focus of analysis and policy. The signposts for inefficiency might be said to include the use of any test or procedure for which evidence has emerged, suggesting that the test or procedure does not work or does not work as well as alternatives that are available. Every comparative trial that does not result in a decreased use of the comparator that worked less well is, thus, evidence in support of the argument that our system of care is inefficient. However, the most compelling evidence comes from studies that compare populations of regions for the use of select tests and procedures and fail to find that those areas that use more of one achieve better health outcomes.14 Similarly, international comparisons often show that the extra usage within the United States fails to improve health-related quality of life, let alone longevity in comparison with other nations.11 Such studies also fail to show that the extra usage engenders greater satisfaction with most aspects of care.

The methods and data sources to estimate the economic burdens of disease, the positive side of health economics, have certainly improved over the years since the first cost-of-illness studies for the nation as a whole were completed by Dorothy Rice and colleagues. Subsequent to the development of the methods of cost-of-illness studies by Rice and others, individual investigators used those methods and the availability of clinical samples to provide highly specific estimates of discrete rheumatic conditions, particularly RA.15 For national estimates, the U.S. federal government has developed an annual survey, the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) to provide reliable estimates of the cost of illness experienced by individuals.16–18 The prior work by Rice relied on separate data sources about ambulatory care, hospital admissions, and nursing homes. The same individuals were not included in each of these data sources; indeed, the data sources were based on samples of medical care encounters rather than of individuals with specific conditions. MEPS provides estimates about every kind of health care for the same individuals and does so through systematic sampling of the U.S. population. For fairly rare conditions, because of the uniformity of data collected in each year, it provides the opportunity to merge multiple years of data so that sample sizes are sufficient to provide estimates of the cost of these conditions reliably.19 Similarly, the batteries of items to measure impact in each domain (e.g., the magnitude of the ambulatory care used) have been vetted through reliability studies comparing survey responses to medical records and billing information. The one aspect of cost-of-illness studies that cannot be replicated using MEPS concerns the indirect costs associated with mortality. Thus a full accounting of the costs of illness would include an estimate of the discounted present value of lost earnings among those who die prematurely. Although mortality rates are elevated for those with inflammatory rheumatic conditions,20–24 in general musculoskeletal conditions are not associated with dramatically higher mortality rates. Therefore the bias in estimates of the costs of these conditions using MEPS data is relatively small.

The comprehensive sampling and reliability of batteries notwithstanding, the findings from the studies of Rice and colleagues about all kinds of conditions in the nation as a whole and the studies about persons with discrete conditions in clinical samples stand the test of time. Thus the early and contemporary studies both highlight the effect of population dynamics, particularly the aging of the population; increase in the cost of care as a function of changes in the kinds of services provided and increase in the unit price of those services; and changing employment circumstances and attendant wage losses on the burden of disease experienced by persons with musculoskeletal conditions.19

The tools of the normative part of economics, not the subject of this chapter, have also evolved over time (Table 31-2). The tools are normative because they are based on the notion that certain levels of health care expenditures unnecessarily divert resources from other uses and that society should have allocative mechanisms, through the market or regulatory means, that redirect resources away from specific conditions or, more frequently, specific treatments for those conditions. That direct medical care expenditures for RA approach “x billion dollars” is a positive statement; that society should not be spending “y billion dollars” on specific treatments for RA is a normative statement; that a treatment achieves an end (e.g., extending life) less expensively than another, the product of a cost-effectiveness analysis, is a tool that may provide a guide in reallocating resources from RA care, in putting in place a policy to implement the notion that spending “y billion” on specific treatments for RA is not a good use of those resources.

Table 31-2 Economic Methods to Assess the Value of Health Interventions

| Drummond and colleagues2 provide a concise review of the methods to estimate the relationship between health care expenditures and the returns of these expenditures in terms of health-related quality of life including one of its domains, employment. When one cannot show that alternative levels of health expenditures will result in improved outcomes, one merely attempts to reduce the wastage of health expenditures, the subject of “cost-minimization studies.” When alternative treatments for a condition are available, one uses “cost-effectiveness analysis,” which shows the relative returns from these alternatives in a common natural metric (e.g., longevity). When one is comparing alternative investments across conditions, one needs an outcome metric that applies to all conditions equally; often the easiest outcome to measure in common terms is the dollar value of lost wages, the subject of “cost-benefit analysis.” However, there are inherent problems in translating outcomes into dollar terms. Accordingly, economists have developed such common metrics as the quality-adjusted life year, which takes into account the value individuals in society place on achieving a common outcome (economists use the term utility for these evaluations and use the term cost-utility analysis for assessing the returns on alternative health expenditures). |

Studies of the Costs of All Forms of Musculoskeletal Disease

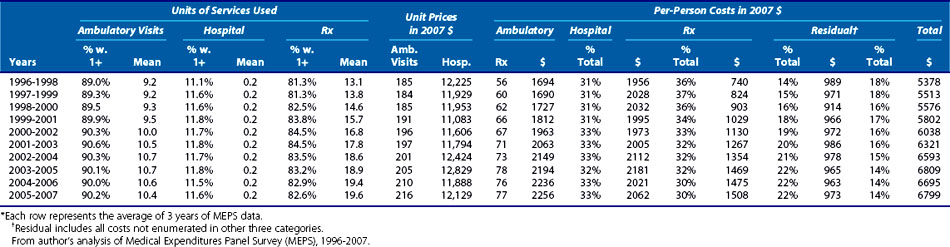

In this section, data from the United States and elsewhere about the economic impact of musculoskeletal conditions as an entire category are presented.* Table 31-3 summarizes information on health care utilization and medical care expenditures for persons with any form of musculoskeletal condition in the United States by averaging 3-year periods between the year in which the MEPS was initiated, 1996, and the last year for which complete data are available, 2007. Three-year averages smooth out individual discrepant values in any one year due to small sample sizes. The first triad of years, thus, incorporates data from 1996 through 1998, whereas the last incorporates data from 2005 through 2007. In the table, all costs are expressed in 2007 terms; all data, however, represent annualized figures. Between 1996-1998 and 2005-2007, there has been little change in the use of ambulatory or hospital care for persons with musculoskeletal conditions. In each triad of years, about 90% of such persons have one or more ambulatory visits and the average number of visits per person has increased only slightly, from 9.2 to 10.4 per year. Similarly, the proportion with one or more hospitalizations has remained relatively constant in the range of 11% to 12% a year, with the average number of admissions holding steady at 0.2 per person per year.

Table 31-3 Units of Services Used, Unit Prices of Services, and Annual Costs per Case in the United States by Year*

The second set of columns in Table 31-3 displays the change in the unit prices of each kind of service between the first and last 3-year periods. The unit price of ambulatory visits increased from $185 in 1996-1998 to $216 in 2005-2007, or by about 17% in real terms. Because we had previously seen that there was little growth in the average number of visits, this suggests that there may have been an increase in the intensity of services provided in ambulatory visits or improved reimbursement for similar services, or some combination of the two; MEPS data do not permit an analysis of the extent to which of these two factors contributed to the increase in the unit prices for ambulatory visits. There was relatively little change in the unit prices associated with hospital admissions among persons with musculoskeletal conditions, with unit prices of $12,225 in 1996-1998 and $12,129 in 2005-2007.

The data in Table 31-3 reflect all the medical care costs incurred by persons with musculoskeletal conditions, regardless of whether they were incurred for that set of conditions or other conditions. Another way to assess the cost of illness is to estimate the increment in total costs beyond those that would be incurred on behalf of persons just like those with musculoskeletal conditions but who do not actually have such conditions. There are two ways to make these estimates: by asking individuals to apportion health care episodes to various causes and by using regression techniques that take into account the health and demographic characteristics of the individuals because the attributions made by the individuals may not be reliable. Using the second method, approximately a third of the costs incurred by persons with musculoskeletal conditions can be attributed to those conditions.

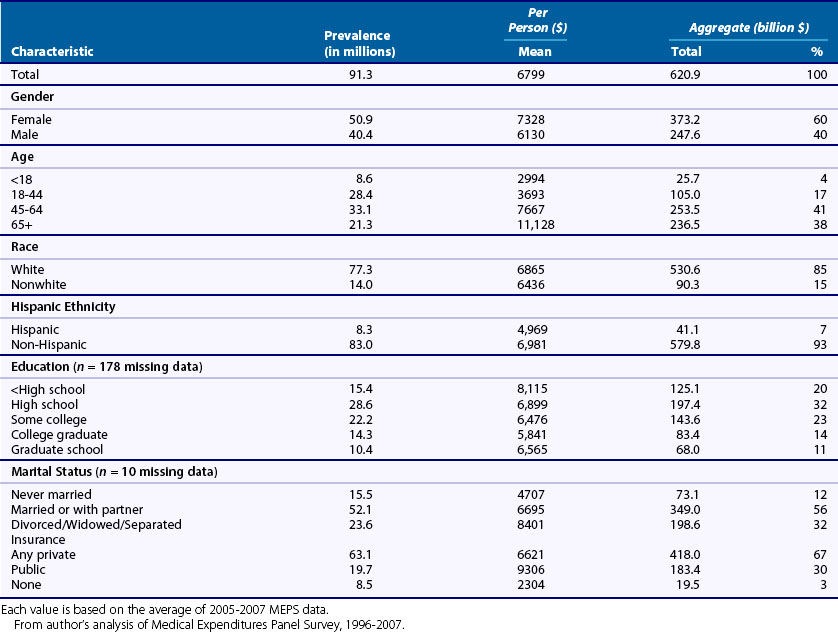

The aggregate medical care costs associated with musculoskeletal conditions are the product of the costs per case, described in Table 31-3, and the number of persons with the conditions at any one time (Table 31-4). As can be seen in the table, the aging of the population is resulting in a substantial increase in the number of persons and percentage of the population with musculoskeletal conditions in the United States. Between 1996-1998 and 2005-2007, the number reporting one or more musculoskeletal conditions increased from 76.0 to 91.3 million, or by more than 20% in relative terms, while the percentage of the population with such conditions rose by 8.9% in relative terms, from 28% to 30.5%. When multiplied by the cost per person in each triad of years covered by the analysis, the aggregate costs rose from $408.6 billion to $620.9 billion in constant dollars, or by about 52% in relative terms. The dual importance of population aging and increases in the cost per case in the dynamics in the aggregate costs of musculoskeletal conditions can be seen by the fact that the percentage increase in the former, more than 20%, and the percentage increase in the latter, 26%, were both substantial.

Table 31-4 Number and Percent of U.S. Population with Musculoskeletal Conditions and Annualized per Case and Aggregate Costs of the Conditions, in 2007 Dollars

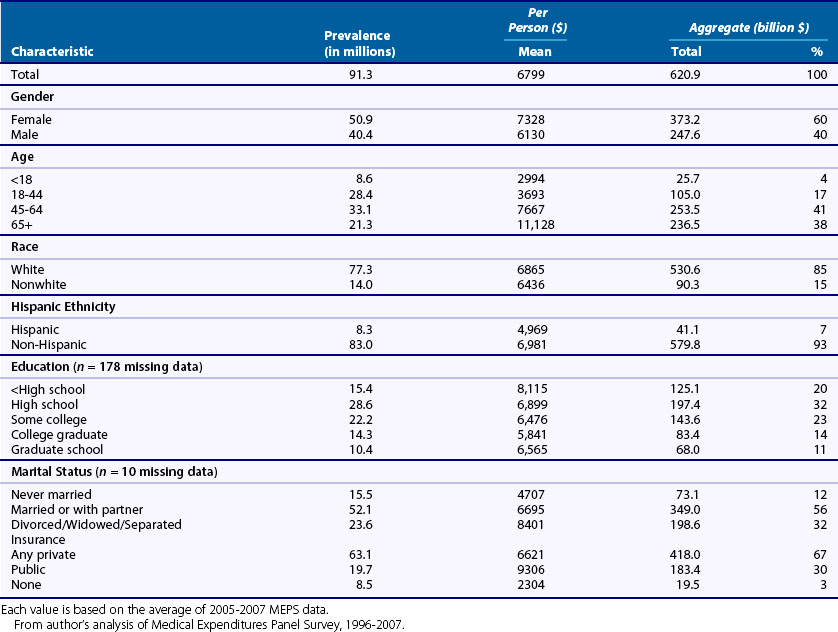

Table 31-5 shows the per-person and aggregate medical care costs in 2005-2007, stratified by demographic characteristics. Musculoskeletal conditions are more prevalent among females; females with the conditions also experience per-person medical care costs that are about 20% higher than men, $7328 compared with $6130. When the higher prevalence and higher per-person costs are combined, aggregate costs are $373.2 billion among females and only $247.6 billion among males, a difference of about 50%. Per-person medical care costs associated with musculoskeletal conditions increase monotonically with age, from a low of $2994 among those younger than age 18 to a high of $11,128 among persons 65 or older. However, because of the number of persons in the 45- to 64-year-old group, aggregate costs are actually slightly higher in the latter group than among those 65 or older, $236.5 billion versus $213.5 billion. Nonwhites with musculoskeletal conditions experience slightly lower per-person costs than whites with these conditions, $6436 versus $6865, a difference of about 7%. On the other hand, Hispanics with musculoskeletal conditions incurred medical care costs of $4969, fully 29% lower than the $6981 incurred by non-Hispanics.

Table 31-5 Prevalence and Medical Care Costs among U.S. Persons with Musculoskeletal Conditions in 2007 Dollars, 2005-2007 (n = 26,373)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree