Diagnostic Ultrasound

Henry L. Lew

Tyng-Guey Wang

Wen-Chung Tsai

Yi-Pin Chiang

INTRODUCTION

With recent advances in computer technology, equipment miniaturization, reduced cost, and ease of use, the clinical applications of diagnostic ultrasound (U/S) have spread across various medical specialties, including musculoskeletal medicine. In this chapter, we review several common pathologies of the shoulder, the elbow, and the knee to demonstrate the utility of diagnostic U/S in musculoskeletal medicine. Detailed procedures for examining the upper and lower extremities have been described in two recent publications (1, 2) and are only briefly mentioned in this chapter.

Two major imaging modalities for detection of soft tissue injuries are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and (U/S). Musculoskeletal U/S is, by no means, a replacement of MRI. Instead, it should be viewed as an extension of our physical examination. Typically, MRI can reveal static features of muscles, tendons, nerves, and bones. However, when compared with U/S, the disadvantages of MRI are (a) its limited accessibility in the clinic, (b) longer examination time, and (c) higher cost. On the other hand, modern musculoskeletal U/S can provide high-resolution and real-time imaging of the nerves, tendons, muscles, and joint recesses, provided that the structures are not too deep or obscured by hyperechoic body parts (3).

Musculoskeletal U/S plays a role not only in the assessment of soft tissue pathologies but also as an adjunct to a number of common interventional procedures. When used appropriately, U/S guidance improves the accuracy of steroid injection into joint cavities, bursa, and tendon sheaths, thus improving its therapeutic efficacy (4, 5) and thereby reducing the risk of iatrogenic complications. By the same token, the application of U/S for regional nerve blocks is also gaining popularity (6, 7). In a recent study, ultrasonography has been successfully used to locate the sacral hiatus for caudal epidural injections (8). Moreover, U/S-guided sacroiliac joint injection, facet joint injection, and medial branch block have been advocated as viable options over fluoroscopy- and computed tomography-guided techniques (9, 10, 11).

U/S images vary with the reflection of the U/S waves, the amount of which defines the echogenicity. Thus, common terms used to describe the anatomic structures in the areas of interest include “hyperechoic,” “isoechoic,” “hypoechoic,” and “anechoic.” In ultrasonography reports, the images are also described in terms of the plane with which the scanning was performed, either longitudinal or transverse. Typically, a linear array probe is used in musculoskeletal examination, as its wider view and higher near-field resolution provide good images of superficial structures. Figure 7-1 shows an example of a U/S machine and the transducer probes. The degree of U/S penetration also depends on its frequency. Probes with higher frequency ranges (7 to 12 MHz) are commonly used to assess very superficial structures. Probes with lower frequency ranges (5 to 7.5 Hz) are often used to assess structures that are deeper, since they allow greater tissue penetration (3). In addition, power Doppler, a technique that takes into account the amount of red blood cells being scanned, can be used to indirectly demonstrate blood flow within the scanned area. In the three sections below, we review the imaging of several common musculoskeletal pathologies, (a) the shoulder, (b) the elbow, and (c) the knee.

EXAMPLES OF SHOULDER PATHOLOGY

Supraspinatus Tendon Tear

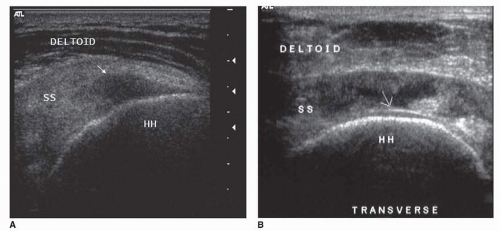

Supraspinatus tendon tears are commonly seen in individuals participating in sports such as baseball, tennis, or swimming. Pain on resisted shoulder abduction suggests pathology of the supraspinatus tendon. On longitudinal scan, a normal supraspinatus tendon should appear as a beak-shaped, echogenic fibrillar structure extending under the acromion, between the humeral head and the subacromial/subdeltoid bursa. On transverse scan, the tendon appears as a band of medium-level echogenic structures, deep to the subdeltoid bursa and superficial to the hypoechoic hyaline cartilage on the humeral head. A partial-thickness tear is demonstrated as a focal anechoic lesion (Fig. 7-2A) or as a mixed “hyperechoic and hypoechoic” focus in the poorly vascularized critical zone of the supraspinatus tendon. The main sonographic features of a full-thickness tear (Fig. 7-2B) include focal nonvisualization through the width of the tendon, as demonstrated in the transverse view (12).

There is inherent interobserver variability in the detection and characterization of supraspinatus tendon tears (12, 13). However, with standardized diagnostic criteria, high-quality scanning equipment, and well-trained sonographers, several studies have reported sensitivities and specificities exceeding 90% in the detection of full- and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (14, 15, 16).

Subacromial-Subdeltoid Bursitis

Subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis is often associated with repeated trauma; and in middle-aged or older individuals, it tends to be linked with overuse or degenerative changes in the rotator cuff (17). A normal bursa should appear on U/S as a thin hypoechoic stripe, covered by a narrow layer of echogenic peribursal fat, located between the underlying supraspinatus tendon and the overlying deltoid muscle. Typically, it is less than 2 mm in thickness, even counting the hypoechoic layer of fluid located between the two sides of the bursa (18).

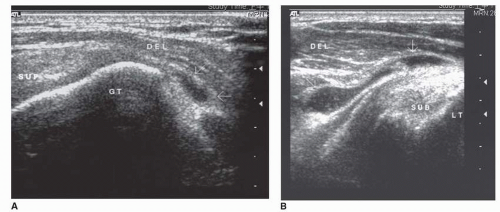

A small effusion in the subacromial/subdeltoid bursa may be identified lateral to the greater tuberosity, especially with the arm extended and internally rotated (Fig. 7-3A). The examiner should be careful not to compress and displace the small amount of fluid. Fluid accumulation within the subacromial/subdeltoid bursa is often noted in patients with infectious or inflammatory bursitis (Fig. 7-3B). However, it can also be observed in patients with full-thickness tear of rotator cuff tendon or in individuals with shoulder impingement syndrome (19). If a needle intervention is deemed necessary, U/S can be utilized to guide bursal fluid aspiration or steroid injection (20).

Bicipital Tenosynovitis

Bicipital tenosynovitis is an inflammation of the long head of the biceps where the tendon passes through the bicipital groove. When the biceps tendon is inflamed, local tenderness in the bicipital groove and an increasing painful arc (painful sensation when the shoulder is flexed from 30 to 120 degrees) are often present. When a clinician is uncertain about the accuracy of the Yergason’s supination test or Speed’s test (21, 22), he or she may consider the use of U/S to improve its diagnosis and treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree