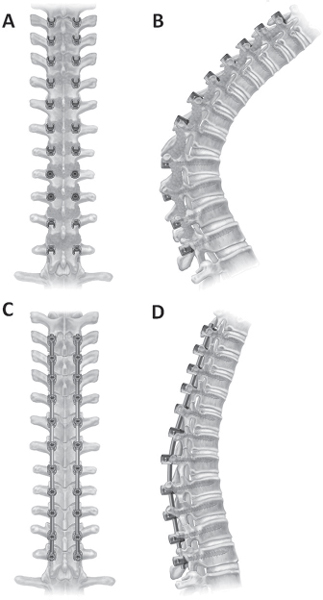

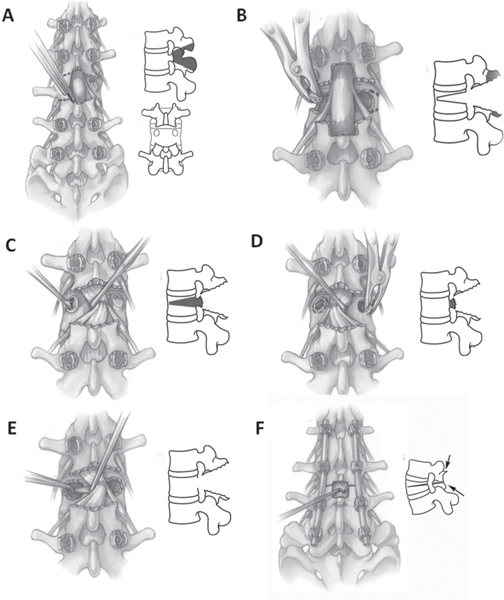

44 This chapter reviews three techniques for posterior-only correction of kyphotic deformities: Ponte or Smith-Petersen osteotomy (SPO), pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO), and vertebral column resection (VCR). Kyphosis can be long, smooth, and rounded or short and angular. An example of a smooth kyphosis is Scheuermann kyphosis (see Chapter 42), whereas sharp, angular kyphosis occurs in conditions like congenital kyphosis (see Chapter 36) or post-traumatic kyphosis (see Chapter 43). Another important aspect is the location of the kyphosis: whether the kyphosis occurs in the thoracic or lumbar spine, or in the region of the spinal cord or the cauda equina. Kyphosis may cause sagittal imbalance, which has been classified into Type I and Type II.1,2 Type I imbalance is segmental, where a portion of the spine is hypolordotic or kyphotic, but overall balance is satisfactory (C7 plumb falls through or within 2 cm anterior to the sacrum) compensated by hyperextension of cranial and caudal segments. A Type II imbalance occurs when the patient cannot compensate because of degenerative changes or the severity of the overall kyphotic deformity. A complete history and physical exam are essential when evaluating a patient with kyphosis or sagittal imbalance. Assessing the underlying cause of the kyphosis will help determine whether an osteotomy is appropriate. Certain patients, despite having a structural deformity, are not physically or mentally fit to undergo a major osteotomy procedure. Utilization of a multidisciplinary team to evaluate a patient’s overall health is beneficial during preoperative planning. The patient’s coronal and sagittal balance should be assessed both clinically and on standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs.3 For sagittal plane deformity, comparison of standing AP and lateral radiographs to prone and/or supine fulcrum-hyperextension long-cassette radiographs will help assess deformity flexibility. These images help classify the deformity into one of three categories: (1) totally flexible, where deformity autocorrects in a prone position; (2) partially flexible, where some deformity correction occurs through mobile segments; and (3) rigid, where deformity does not correct.2 Flexion-extension radiographs may also identify areas of pseudarthrosis in prior fusion masses. Assessment of the spinal canal is an important part of preoperative planning for correction of a kyphotic deformity. If there is a solid fusion, the spinal canal will be patent. However, areas adjacent to a prior fusion are often degenerated, with coexistent spinal stenosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help with this assessment in areas without prior fusion or with uninstrumented fusions, or where titanium implants were used. Stainless steel implants make MRI less useful due to metallic artifact. Computed tomography (CT) or CT myelography may be more helpful. SPOs are commonly used for the treatment of a smooth, gradual fixed kyphosis.4 An important point to clarify is the often interchangeable nomenclature used in the literature for this osteotomy. As originally described, SPOs were performed through ankylosed segments.4 Ponte more recently described a technically similar osteotomy that was performed through nonfused regions in patients with Scheuermann kyphosis. While both describe a similar technique, the osteotomy should be called an SPO if done through fused segments and a Ponte osteotomy if performed through unfused segments. For ease, this osteotomy is called an SPO in this chapter. An SPO involves creating a chevron trough in the posterior elements by removing the posterior bone, ligaments (supraspinous, interspinous, and ligamentum flavum) and facet joints (Fig. 44.1A–D). A wide facetectomy is required, as posterior compression closes down the neural foramina and may cause nerve root impingement. An SPO requires a mobile disk space for closure of the posterior and middle columns and opening of the anterior column. In general, the degree of kyphotic correction with a single SPO is 10 degrees/level or 1 degree/mm bone resected.5,6 A classic example for the use of SPO is Scheuermann kyphosis, where multiple SPOs are performed at the apex of the deformity. Another potential indication for multiple lumbar SPOs would be in a patient with mild sagittal imbalance (6–8 cm), where several lumbar SPOs along with anterior interbody structural support at L4–L5 and L5–S1 would help restore sagittal balance. When a smooth kyphosis lacks mobile anterior disks, a PSO may be an alternative. More commonly, however, pedicle subtraction procedures are used for sharp, angular kyphosis or sagittal imbalance greater than 10 cm.7–9 A PSO may be performed in the thoracic spine, but more commonly is done in the lumbar spine (at L2 or L3). More distal PSOs carry an increased risk of neurological injury and have fewer distal fixation points.5 A PSO requires resection of the posterior elements and pedicles and decancellation of the vertebral body in a V-shaped fashion through the transpedicular corridor (Fig. 44.2A–F).8 With osteotomy closure, a large cancellous bone contact area is present as the posterior and middle columns are closed, and the osteotomy hinges on the anterior vertebral body. More aggressive resections include the disk space above the decancellated segment, which may lead to greater kyphotic correction. In addition, asymmetrical pedicle subtraction procedures have been described that can aid in the correction of any concomitant coronal deformity. On average, 30 to 40 degrees of sagittal plane correction can be achieved with a lumbar PSO, and less (~ 25 degrees) with a thoracic PSO2,7,9,10 (Fig. 44.3). Fig. 44.1 Diagram of a Smith-Petersen (Ponte) osteotomy. (A) Placement of pedicle screw fixation prior to starting osteotomies. (B) Resection of posterior elements including portion of spinous process, interspinous ligaments, ligamentum flavum, and facets. (C) Closure of the osteotomies and placement of rods. Multiple SPOs performed through apex of kyphotic deformity. (D) Correction obtained through cantilever and compression techniques on posterior rods, usually obtaining ~ 10 degrees of kyphosis correction per level. VCRs are most often used in the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine for the treatment of angular kyphosis or sagittal imbalance associated with coronal malalignment.11,12 A thoracic VCR necessitates the performance of a costotransversectomy followed by resection of all the posterior elements including the facet joints at the cranial and caudal levels, and the entire vertebral body along with the adjacent intervertebral disks (Fig. 44.4). The more sharp and angular a thoracic kyphosis, the easier it is to perform a posterior VCR. Key points to remember while performing a VCR are (1) use of temporary rod placement prior to performing the VCR to prevent intraoperative spine subluxation, (2) placement of an anterior structural cage to prevent spinal cord buckling and excessive segment shortening, (3) extensive laminectomy one level above and below the VCR is needed to avoid spinal cord impingement, and (4) rib strut grafts can act as bridge grafts to provide a bony surface for the fusion over the laminectomized region after osteotomy closure. A posterior VCR can offer kyphotic correction in the range of 40 to 50 degrees.11–13 Fig. 44.2 Diagram of a pedicle subtraction osteotomy. (A) Wide central decompression is performed from the pars above to the pars below the osteotomy-level pedicle. (B) Exiting nerve roots are identified and pedicles are resected down to ventral vertebral body. (C) Vertebral body is decancellated through pedicles bilaterally. (D) Wedge resection of lateral vertebral body with apex anterior is performed. Vertebral body wedge resection needs to be symmetric to facilitate osteotomy closure and prevent iatrogenic coronal decompensation. (E) Dorsal vertebral body is decancellated until thin cortical rim is left. Using a reverse-angled curette or Woodson elevator, the dorsal vertebral body is pushed down ventrally into osteotomy. (F) Osteotomy is closed and central decompression is reassessed for residual areas of neural compression.

Corrective Osteotomies for Kyphosis

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

![]() Treatment

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree