84 Clinical Features and Treatment of Scleroderma

Historical PERSPECTIVE

Some consider that the first description of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) was put forth in 1753 by Cario Curzio (Naples, Italy).1 However, a careful review of the reported case suggests that the diagnosis was really scleroedema because of the distribution of the skin changes and the fact that the 17-year-old female improved with bloodletting, warm milk, and small doses of quicksilver. In 1836, Fantonetti (1791-l877), a Milanese physician, became the first to use the word scleroderma to designate a skin disease in an adult. However, it is likely that this patient also had scleroedema. The first convincing case of scleroderma was reported in 1842; then several acceptable cases were published before 1847, when Gintrac used the term sclerodermie, establishing this condition as a specific clinical entity.2 By 1860, numerous cases had been reported, and articles reviewing the disease were published. Maurice Raynaud (1834-1881) described a patient with sclerodermie and cold-induced “asphyxie locale”—this was the first description of Raynaud’s phenomenon in scleroderma. Sir William Osler described scleroderma while at Johns Hopkins Hospital between 1891 and 1897.3 Osler recognized the systemic nature of the disease and was so impressed with the severity of scleroderma that he wrote:

Matsui (Japan, 1924) emphasized the importance of visceral involvement as part of scleroderma based on several autopsies. Goetz (Capetown, 1945) further confirmed the multisystem involvement and suggested that the disease be named progressive systemic sclerosis.4

The concept of subtypes of scleroderma began in 1964, when Winterbauer reported cases with the CRST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) syndrome.5 A similar group of patients was reported in 1920 and was named after the authors—the Thiberge-Weissenbach syndrome. Velayos and colleagues recognized that esophageal dysmotility was common in these patients, so it is now called the CREST syndrome.6 In 1969, 58 autopsy cases of scleroderma were compared with matched controls.7 The organs found to be frequently and significantly involved by this disease were the skin, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, kidneys, skeletal muscle, and pericardium. This report first described the systemic nature of scleroderma vascular disease with findings of both kidney and lung arterial changes. In 1979, Rodnan introduced a clinical method to evaluate the extent of skin disease.8 Steen and Medsger with others conducted extensive surveys of large populations of scleroderma patients, defining the clinical course and specific subtypes of disease. In the 1970s, an expert subcommittee established diagnostic criteria, and Leroy and colleagues suggested the classification of two major subsets of disease defined by skin involvement: limited and diffuse. Later, work by several investigators recognized that scleroderma has an autoimmune basis with occurrence of specific autoantibodies associated with subtypes of disease and useful in predicting disease course.

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

Scleroderma is a rare disease with an estimated incidence of approximately 18 to 20 cases per million population per year, and a prevalence of 100 to 300 cases per million population. Reported rates vary by method of ascertainment, population under study, and definition of disease. Scleroderma is found in all races and in various geographic areas, but the prevalence and severity of disease vary among different racial and ethnic groups. The prevalence of scleroderma appears to be greater in the United States, where it has been estimated at 24.2 per 100,000, than in Europe, where recent studies in Iceland, England, France, and Greece have estimated rates ranging from 7.1 to 15.8 per 100,000.9 In Australia, estimates are similar to those in the United States, and Japan has a lower reported prevalence—similar to that in Europe.10 The highest scleroderma prevalence is reported among Choctaw Native Americans, in whom the disease appears to be more severe.11 Several surveys in the United States show that African-Americans have a higher age-specific incidence rate and experience more severe disease than whites.12 Occurrence is not different from urban to rural areas. Occasional reports have described unusually large numbers of cases of scleroderma observed in restricted geographic regions, suggesting nonrandom distribution of the disease. For example, in a rural area in the province of Rome, a geographic cluster of scleroderma and disease with related features was reported, suggesting prevalence 1000 times greater than expected.13 Likewise, a study in the United Kingdom reported a higher prevalence of scleroderma in three geographic areas clustered near airports compared with other areas of the United Kingdom.14

The average age at onset is between 35 and 50 years, and the disease is more common among women (3 to 7 : 1 female-to-male ratio). Disease onset in the elderly is well described; it is uncommon for the disease to become manifest before the age of 25 years. Older age at onset is associated with increased risk for multisystem disease and, in particular, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). A progressive increase in the incidence of scleroderma has been noted with increasing age. Over the period from 1963 to 1982, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the highest rates of scleroderma were observed between the ages of 45 and 54 years in black women, and between the ages of 55 and 64 years in white women.15 Younger age at disease diagnosis among black women compared with white women was reported from Detroit, Michigan.9

Survival

Mortality among scleroderma patients is high, and most deaths are attributed directly to the disease manifestations.16 In fact, the prognosis in scleroderma is highly variable, and survival is influenced by disease subtype, degree of internal organ involvement, and comorbid conditions. Factors associated with poor prognosis include diffuse skin disease, the presence of pulmonary disease (particularly PAH), renal involvement, multisystem disease, evidence of heart disease, older age at disease onset, and the presence of anemia. The standardized mortality rate (SMR) is the measure used to assess the relative mortality of a disease in comparison with the general population. Surveys of scleroderma patients report an SMR from 1.46 to 7.1. A survey found that among 284 scleroderma patients who died, the median disease duration as estimated from the onset of Raynaud’s phenomenon until death was 7.1 years for patients with diffuse skin disease, and 15.0 years for those with limited skin disease. Among non–scleroderma-related causes of death are, as expected, infection, malignancy, and cardiovascular events. Although premature atherosclerosis has been implicated as the cause of early death in other inflammatory autoimmune diseases, an increased prevalence of macroscopic coronary artery or cerebrovascular involvement beyond that expected in the general population has not yet been demonstrated in scleroderma.

Several studies suggest that the main cause of death has changed over time. Improved survival in recent years is thought to be secondary to more effective treatments for specific organ-based complications. It seems clear that the natural history of scleroderma renal complications has changed secondary to the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for renal crisis. Historically, patients with scleroderma renal crisis had 1-year survival less than 15%.17 Recent case-control studies conducted after the introduction of ACE inhibitors suggest greater than 85% 1-year survival. Pharmacologic prevention and treatment of interstitial lung disease and PAH are thought to have an impact. Cohort studies have demonstrated improved overall survival among scleroderma patients. At one scleroderma center, 10-year survival from disease diagnosis improved from 54% in the 1972-1981 group to 66% in the 1982-1991 group.18 Another survey found that 5-year survival among diffuse cutaneous scleroderma patients improved from 69% in 1990-1993 to 84% in 2000-2003 (P = .018), whereas 5-year survival among limited cutaneous scleroderma patients remained unchanged at 93% and 91%, respectively.19

Environmental Exposures

Geographic clustering of scleroderma cases suggests that environmental exposure may be responsible for the disease, but definitive proof is still lacking. Epidemics of scleroderma-like illness following exposure to dietary (l-tryptophan or adulterated rapeseed oil), occupational (silica), or pharmacologic toxins (e.g., bleomycin, gadolinium-based contrast media) support the idea that environmental exposure can trigger a fibrotic disease. Typical scleroderma is found among coal miners and workers exposed to silica, particularly male workers. A meta-analysis of the risk of silica exposure found that the combined estimator of relative risk (CERR) was 1.03 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.74 to 1.44) in females and 3.02 (95% CI, 1.24 to 7.35) in males.20 Although occupational exposure to solvents (paint thinner or removers, mineral spirits, trichloroethylene, trichloroethane, perchloroethane, gasoline, aliphatic hydrocarbons, halogenated hydrocarbons, and BTX solvents containing benzene, toluene, or xylene) or polyvinyl chloride is reported to be associated with scleroderma, the role of these agents in causing disease is controversial and remains unproven. Likewise, case reports have suggested that silicone present in breast implants has triggered scleroderma, but large epidemiologic surveys have not found a greater incidence of scleroderma than expected in women with breast implants or exposure to silicone. Drugs implicated as potentially causative for systemic sclerosis (SSc)-like illnesses include bleomycin, pentazocine, and cocaine.

Genetic Factors

Although the absolute risk for family clustering remains low (1%), studies from Australia and the United States suggest that a family history of scleroderma increases the risk of disease, with a relative risk of first-degree relatives around 14 and of siblings in the range of 15 to 19.21 Genetic factors were investigated by a survey of 42 twin pairs among which at least one twin had scleroderma.22 The overall concordance rate was low at 4.7%, and was similar between monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs. Although an association between major histocompatibility complex (MHC) alleles and scleroderma has been reported, this has not been confirmed consistently.23 This finding argues against strong genetic susceptibility and favors a role for environmental and/or epigenetic events.

Overview of Clinical Features

Diagnostic Criteria

A subcommittee of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) established diagnostic criteria based on a consensus of experts who evaluated a multicenter survey of scleroderma patients compared with other patient groups (Table 84-1).24 The purpose of these criteria was to provide diagnostic certainty and consistency for research and other documentary exercises. The single finding of thickening of the skin typical of scleroderma proximal to the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints of the hands is considered a major criterion confirming the diagnosis. This includes changes on the face, arms, legs, or trunk. If skin thickening is found only distal to the MCP joints, then two of three minor criteria (digital pits, sclerodactyly, and pulmonary fibrosis on chest radiograph) must be present to confirm the diagnosis. These criteria are very specific (98%) for making the diagnosis of scleroderma but are considered too restricted in that they exclude patients with early or mild expression of the disease. Many patients with skin thickening limited to the fingers and some with no skin changes are recognized to have systemic disease and yet do not meet the ACR criteria. Large longitudinal surveys confirm that a high percentage of patients with definitive Raynaud’s phenomenon and typical scleroderma nail-fold capillary changes, along with scleroderma-specific autoantibodies, develop scleroderma within a 2- to 4-year period of follow-up.25 Therefore, although the ACR criteria have a definite role in defining cases for research purposes, the clinician needs to take into account subtle features of the disease to make an early diagnosis for management purposes. Most experts would accept the finding of three of the five features of the CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias) to make a clinical diagnosis of scleroderma. In clinical practice, one needs to recognize that some patients will not develop skin changes and yet they do have systemic disease (systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma), and many patients will present with partial expression of the disease (e.g., Raynaud’s with nail-fold changes only) and later will develop well-defined disease. Experts argue that patients with partial expression, especially when a specific scleroderma-related autoantibody is present, should be considered to have a diagnosis of scleroderma and should be treated accordingly.

Table 84-1 Establishing Diagnosis of Scleroderma

| ACR Criteria | |

| Must have (a) or two of (b), (c), or (d) | |

| CREST Criteria | |

| Must have three of the five features | |

| Minor Criteria*† | |

| Must have all three |

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CREST, calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias; CXR, chest x-ray; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; MCPs, metacarpophalangeal joints; MTPs, metatarsophalangeal joints; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

* Some experts continue to classify patients with minor criteria only as undifferentiated connective disease with scleroderma features.

† Proximal areas include the face. Autoantibody includes anticentromere, antitopoisomerase (Scl-70), and anti-RNA polymerase III.

Classification and Clinical Subsets

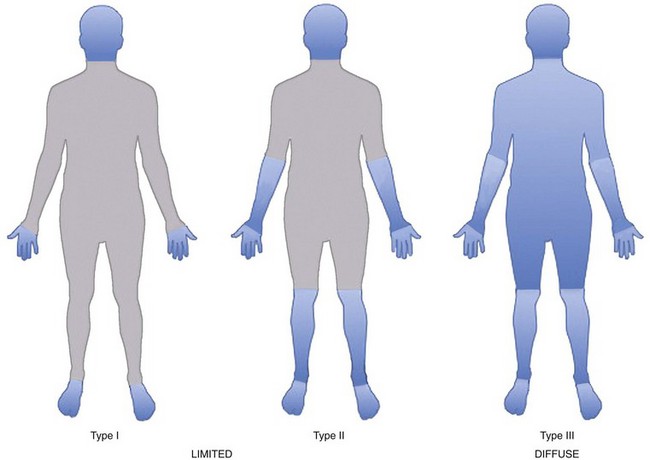

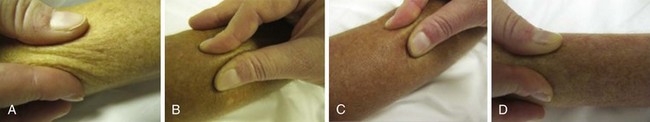

The scleroderma disease process is complex, and its clinical expression is very heterogeneous such that the disease is expressed in several distinct clinical phenotypes. Classifying patients into subtypes is useful both for investigative purposes and for clinical practice. A specific subtype can define increased risk for internal organ involvement and overall prognosis. The traditional way to classify patients is by the degree of skin thickening as determined by physical examination. The skin is scored by pinching a fold and deciding whether it is abnormally thickened because of the scleroderma process. A committee of experts decided by consensus that two major groups of patients can be identified based on the distribution of skin changes and associated clinical and laboratory outcomes as observed (Figure 84-1).26 Patients are considered to have diffuse skin disease if skin changes are found proximal to the elbows and/or knees or on the trunk, excluding the face. These patients tend to have higher risk of multisystem disease and poor survival. Patients are considered to have limited disease if skin changes occur distal to the elbows and/or knees and not on the trunk. Facial skin thickening can be present in the limited group. Some argue that the term CREST syndrome should be eliminated, and that these patients should be classified in the limited skin group. Others feel that the CREST syndrome is a unique subtype within the broader group of limited skin diseases with a distinct disease course.

Another less popular classification system divides patients into three groups based on skin changes: limited (fingers only), intermediate (skin to the elbows or knees), and diffuse (skin above the elbows and/or knees and/or trunk). Studies using this classification have found that the intermediate group had distinct clinical outcomes, including an intermediate survival statistic between limited (best) and diffuse (worse).27 A subtype of disease with absence of skin fibrosis has been recognized and is referred to as scleroderma sine scleroderma. Serologic studies have shown that the presence of specific autoantibodies predicts clinical features of the disease, suggesting that the classification might be based on the autoantibody type (see “Natural History”). Patients with early or partial expression of the disease (e.g., Raynaud’s phenomenon alone with nail-fold capillary loop abnormalities) are often diagnosed as having undifferentiated connective tissue disease (UCTD). About 20% of these patients will develop clear features of scleroderma, usually within 2 to 4 years of follow-up.25

Natural History of Disease

The natural history of scleroderma varies a great deal depending on the specific subtype of disease established in a patient. Scleroderma tends to be a chronic monophasic illness, unlike systemic lupus erythematosus, which is characterized by quiescence interrupted by sudden disease flares. The pattern of the disease and the degree or type of internal organ involvement are variable but generally can be predicted by the extent of skin affected. Internal organ disease is more severe in patients with the diffuse skin type than in those with limited scleroderma. The disease course is usually indolent in patients with sclerodactyly alone. In these patients, years pass from onset of Raynaud’s phenomenon before obvious organ dysfunction manifests, although explosive multisystem disease can emerge rapidly over several months in patients with widespread skin changes. Likewise, when patients with diffuse skin disease experience skin improvement, new internal organ disease is generally uncommon. The degree of skin thickening varies in extent and progression over time, with some cases stopping after several months with relatively mild disease, and others progressing over years to involve most of the body surface (see “Skin Involvement”).

Patients classified in the limited scleroderma group may have intermediate skin involvement, with skin extending over the hands and forearms or lower legs but not over the trunk. These patients appear to have an intermediate disease course that is not as severe as that of patients with widespread skin disease. The intermediate group has decreased survival compared with patients with only sclerodactyly. Although the degree of skin disease provides a rough guide by which to predict disease course, many exceptions have been noted. Variability is associated with other clinically defined factors, including age, gender, and racial/ethnic background. Late age at onset increases the risks for PAH and poor survival. Males may have a more aggressive disease course than females. African-American or Native American race predicts a worse disease course and worse multisystem disease.9

General Principles of Disease Evaluation

Measuring Disease Activity and Severity

Measurement of changes in skin thickness (modified Rodnan skin score) is used as a surrogate measure of disease severity and a predictor of extent of organ involvement and overall prognosis (see skin manifestation section).28 It is also used as a quantifiable, easily obtainable, and valid score, changing over time in response to therapy. Thus, the skin score is now used as a measure of disease activity and is employed in clinical trials as a primary outcome measure. In patients with diffuse skin disease, improvement in skin score is associated with better clinical outcome. A core set of items covering 11 domains (skin, musculoskeletal, cardiac, pulmonary, renal, gastrointestinal, health-related quality of life measures, global health, Raynaud’s phenomenon, digital ulcers, and the biomarkers erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein) is now considered to provide the minimum clinically relevant treatment effect values, as defined by consensus of experts in the field.29 More detailed scales for specific organs are also in use. For example, a skin assessment tool combines the modified Rodnan skin score with a visual analogue score (VAS) of the patient’s assessment of skin activity, a VAS score of the physician’s assessment of skin activity, and measures obtained by a durometer.30 A gastrointestinal scale has been developed to define mild to severe gastrointestinal disease.31 Experts who reviewed current outcome measures in assessing PAH as related to scleroderma decided that lung vascular and pulmonary arterial pressures and cardiac function as measured by right heart catheterization and echocardiography; exercise testing as measured by 6-minute walk and oxygen saturation with exercise, New York Heart Association functional class, severity of dyspnea on a VAS, and measures of quality of life and function obtained by Short Form 36 and the Health Assessment Questionnaire and Disability Index (HAQ-DI); and physician global scale as measured by survival are all important measures. Other outcome measures that are considered valid include Raynaud’s condition score for Raynaud’s severity, forced vital capacity, and Mahler’s dyspnea index to follow interstitial lung disease, serum creatinine, blood pressure, and complete blood count during a scleroderma renal crisis, as well as serum creatine phosphokinase to follow muscle disease.

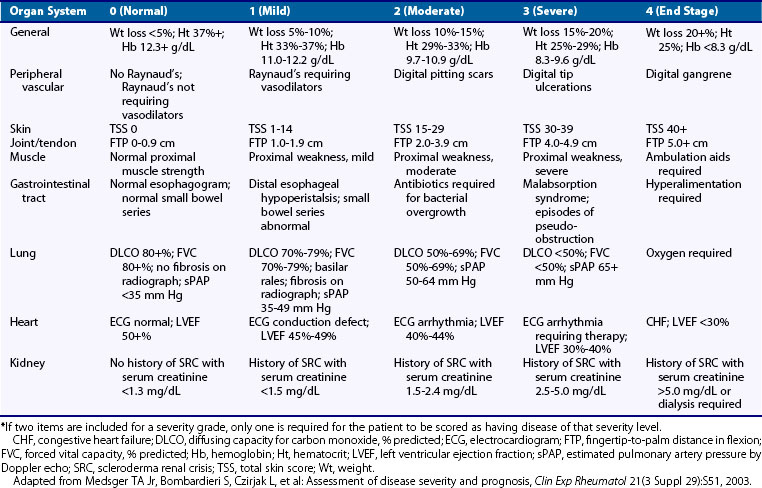

A scleroderma severity scale has been developed by Medsger to assess disease severity status in individual patients both at a given time and longitudinally (Table 84-2).32 This scale is based on scoring that ranges from 0 (normal) to 4 (end-stage) for each organ system involved in scleroderma, including a general measure, along with measures of the peripheral vascular system, skin, joints and tendons, gastrointestinal tract, lung, heart, and kidney. This severity scale is now used by many experts to define the status of a patient in clinical trials and in research investigating risk for clinical outcomes.

The Health Assessment Questionnaire and Disability Index (HAQ-DI) is a self-administered tool initially developed for rheumatoid arthritis to measure functional impairment; it has been validated and used in scleroderma as well, where it correlates with objective physical signs and reflects the disease course. Higher degrees of impairment are found by HAQ scores in scleroderma patients with diffuse skin disease, higher skin scores, abnormal hand function, presence of myopathy or friction rubs, and joint pain.33 Change in the HAQ score occurs with changes in skin involvement and progressive organ disease.34 The HAQ is useful in evaluating patients with Raynaud’s and correlates with the severity and presence of digital ulcers. VAS instruments that assess disease in various domains specific for scleroderma are added to the HAQ to focus on scleroderma-specific issues, including measures of Raynaud’s and digital ulcers. In addition, the Short Form 36 survey, a simple self-report tool composed of 36 items in 8 domains, is used to assess health-related quality of life.

Developing an activity scale is much more challenging than establishing severity measures. Attempts include evaluating changes in skin score and evidence of active lung disease and documenting congestive heart failure or a scleroderma renal crisis. A composite score generated as a physician global assessment has been used to measure disease activity. This simple global score has merit but is influenced, besides activity, by organ severity and irreversible damage.35 A European study group developed the Valentini disease activity index, which currently is used in clinical studies.36 This index provides more of an organ-specific assessment than a measure of global activity. The Medsger disease severity scale has the potential to measure activity if used in studies with serial observations, when individual organ scales can be combined into a composite score. Intermediate clinical and serologic biomarkers are under investigation as candidates to define and predict disease activity and prognosis, but none has proved reliable or valid. Measures of acute phase factors (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) are nonspecific but are included by expert consensus in some systems designed to measure disease activity. Currently, no “gold standard” is available to measure disease activity in scleroderma, and defining biomarkers or other measures of disease activity remains a major challenge.

Autoantibodies

Measurement of the autoantibodies present in scleroderma can be helpful in determining the clinical features and prognosis of the disease, in that specific scleroderma-related autoantibodies have been established as strong predictors of disease outcome and the pattern of organ complications (Table 84-3).37 The three most frequently observed types of scleroderma-specific autoantibodies are anticentromere, antitopoisomerase I, and anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies.

Table 84-3 Autoantibodies and Associated Phenotypes in Scleroderma

| Antigen | Subtype | Clinical Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Topoisomerase 1 (Scl70) | Diffuse | Pulmonary fibrosis, cardiac involvement |

| Centromere (protein B, C) | Limited | Severe digital ischemia, PAH, sicca syndrome, calcinosis |

| RNA polymerase III | Diffuse | Severe skin disease, tendon rubs, renal crisis (±sine scleroderma) |

| U3-RNP (fibrillarin) | Diffuse or limited | Primary PAH; esophageal, cardiac, and renal involvement; muscular disease |

| Th/To | Limited | Pulmonary fibrosis, rare renal crisis, lower GI dysfunction |

| B23 | Diffuse or limited | PAH, lung disease |

| Cardiolipin, β2GPI | Limited | PAH, digital loss |

| PM/Scl | Overlap | Myositis, pulmonary fibrosis, acro-osteolysis |

| U1-RNP | Overlap | SLE, inflammatory arthritis, pulmonary fibrosis |

GI, gastrointestinal; GPI, glycoprotein I; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RNP, ribonucleoprotein particle; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Adapted from Boin F, Rosen A: Autoimmunity in systemic sclerosis: current concepts, Curr Rheumatol Rep 9:165–172, 2007.

Raynaud’s Phenomenon

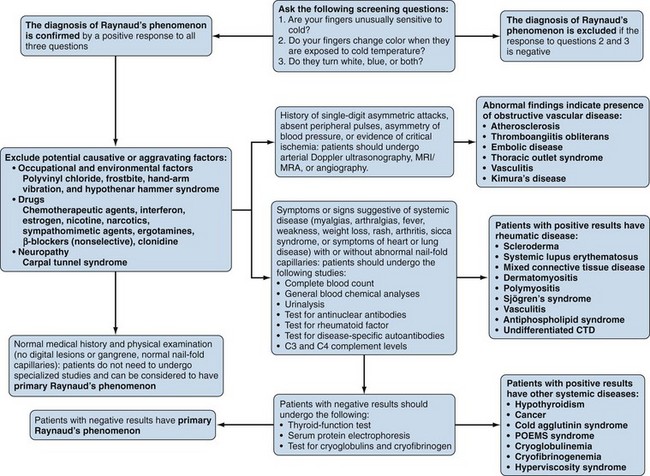

Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is an exaggerated vascular response of the digital arterial circulation triggered by cold ambient temperature and emotional stress. The diagnosis of RP is based on a history of excessive cold sensitivity and recurrent events of sharply demarcated pallor and/or cyanosis of the skin of the digits (Figure 84-2). Blanching reflects digital arterial vasospasm, and cyanosis occurs secondary to the deoxygenation of sluggish venous blood flow. Some skin blushing (redness) may follow owing to reactive hyperemia after regular blood flow has been restored. Raynaud’s phenomenon occurs in 3% to 15% of the general population. It is more common among females (3 to 4 : 1) and is likely to begin before 20 years of age. During cold exposure (particularly during shifting temperatures and winter months), Raynaud’s attacks increase in frequency and intensity. Raynaud’s phenomenon can be categorized clinically into primary and secondary forms (Figure 84-3). Primary RP occurs when no disease process is associated with recurrent vasospastic events. Distinguishing primary RP from that associated with an underlying disorder is frequently challenging. Young age at onset (<20 years), symmetric manifestations of symptoms, mild to moderate severity, no association with digital ulceration or tissue gangrene, normal nail-fold capillary examination, and a negative antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer are all indicative of primary RP.38 Secondary RP occurs in a variety of settings, including connective tissues disorders and other rheumatic conditions, occupational trauma (e.g., hypothenar hammer syndrome), the use of certain drugs (e.g., antimigraine agents, ergotamine derivatives, bleomycin), increased blood viscosity, and compressive or obstructive vascular disease (e.g., thoracic outlet syndrome, atherosclerosis, thromboangiitis obliterans).

Figure 84-2 Active Raynaud’s phenomenon with well-demarcated pallor at the fingertips in a scleroderma patient.

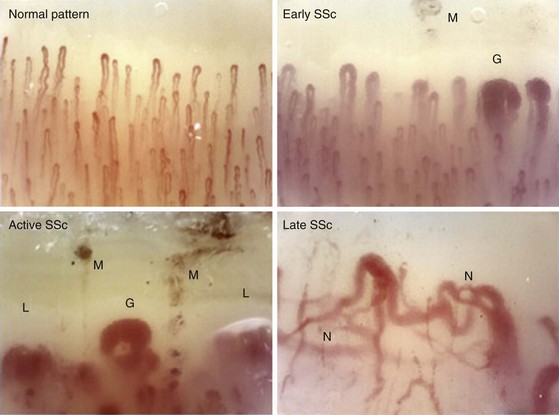

Nail-fold capillaroscopy is the tool most commonly used at the bedside to distinguish patients with primary RP from those with scleroderma or another rheumatic disease. Maricq and associates first described the abnormal pattern of nail-fold capillary vessels seen in scleroderma.39 The simplest method of detection is to coat the skin of the nail fold with immersion oil and then view the area using a bifocal dissecting microscope or a hand-held device such as an ophthalmoscope set at 20 or 40 diopters. A computerized nail-fold videocapillaroscopy technique is used in specialty centers. This technique provides enhanced digital images that can assess local blood flow and follow the disease course.40 Although patients with primary RP may have normal, thin, palisading nail-fold capillary loops (Figure 84-4), in secondary RP, capillary loop dilation/enlargements and dropouts represent the salient features. Patterns of capillary abnormalities appear to correlate with the course of systemic disease manifestations. Capillary dilation (giant capillaries), microhemorrhages, and some disorganization of the capillary network are typical of early disease; dropouts, avascular areas, and signs of neoangiogenesis with bizarre architectural distortion manifest at later stages of scleroderma.41,42 Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with RP and abnormal nail-fold capillary changes will develop clinical features of scleroderma, usually within a 2- to 3-year period.25 Patients presenting with RP, nail-fold capillary changes, and the presence of a scleroderma-related autoantibody have a 70% to 80% chance of developing scleroderma within 2 to 3 years from presentation. Therefore, capillaroscopy represents an important standard tool that can be used to examine patients presenting with RP.

In scleroderma, RP and digital ischemia are the clinical manifestations of both fixed structural vascular disease and abnormal regulation of local vasomotor control. Cold-induced vasoconstriction of peripheral blood vessels normally occurs via sympathetic stimulation. Abnormal thermoregulation is associated with a nonvasculitic vasculopathy characterized by endothelial dysfunction and a fibrotic proliferation, which produces an increase in collagen content of the intima of small and medium vessels and causes loss of vessel flexibility and obliteration of their lumina. Digital pitting with loss of fingertip tissue and small, painful, superficial ulcerations are very common and usually are noted secondary to disease affecting the small arteries and arterioles of the skin (Figure 84-5). Large, deep ulceration of the distal portion of the finger is a consequence of larger-vessel (e.g., digital artery) occlusion associated with severe vasospasm. The latter event usually presents as a sharp demarcation of the distal digit with intense, localized pain secondary to ischemia. Failure to reverse these events may lead to loss of the whole digit or limb secondary to deep tissue infarction.

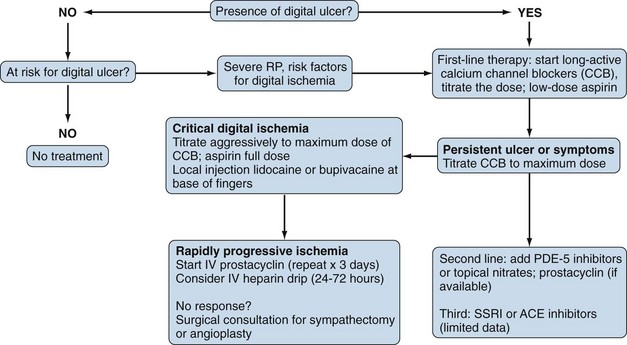

Treatment of Raynaud’s Phenomenon and Digital Ischemia

The primary goal in the management of RP is prevention of digital ischemia through the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic measures (Figure 84-6). In the setting of acute digital ischemia, rapid intervention using both treatment modalities is required. The primary and most important nonpharmacologic therapy for prevention is avoidance of cold ambient temperatures, particularly transitioning from a warm or hot environment to a cold one. A warm ambient temperature reduces the frequency and severity of RP. All patients with RP should understand that clothing should be layered and loose-fitting, with the goal of maintaining a warm core body temperature, not just warmth of the affected extremities. Patients who have an acute ischemic event are best treated with rest in a warm environment (home or hospital), insulated from cold temperatures. Other potential therapies include minimizing emotional distress (reducing sympathetic tone) and avoiding aggravating factors such as smoking, sympathomimetic drugs (e.g., preparations for the common cold), migraine headache medications (e.g., serotonin agonists), and nonselective β-blockers (e.g., propranolol). Although behavioral therapies (biofeedback, autogenic training, and classical conditioning) are reported to be helpful, their benefit is controversial, and they play no role in the management of acute ischemia related to scleroderma.43 In fact, biofeedback alone is not helpful for primary RP.

Drug therapy for RP in scleroderma includes the use of a variety of oral or systemic vasodilators. Calcium channel blockers are considered to be first-line therapeutic agents in the treatment of RP. This class of medication works primarily by inducing arterial vasodilation through direct inhibition of contraction of vessel smooth muscle cells; however, these agents provide additional benefits by reducing oxidative and inhibiting platelet activation.44,45 Most published studies evaluating the efficacy of calcium channel blockers in RP have employed dihydropyridines (e.g., nifedipine, amlodipine, nisoldipine, isradipine, felodipine), and few have looked at nondihydropyridines, which appear to be more efficacious in primary than in secondary RP.46,47 A meta-analysis of 17 studies evaluating the efficacy of short- and long-acting formulations of calcium channel blockers reported a 33% reduction in attack severity and a near 50% reduction in the number of attacks per week.48 The current recommendation is to use an extended-release formulation of a calcium channel blocker for treatment of nonurgent RP. The dose should be titrated to clinical efficacy, but common side effects (hypotension, headache, pedal edema) should be monitored. For urgent cases of RP, a short-acting formulation of the medication is preferred, but titration should be carefully monitored. Although calcium channel blockers are the agents most likely to be effective, a host of other vasodilators are used, including nitrates, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (e.g., sildenafil), intravenous prostaglandins, and sympatholytic agents (e.g., prazosin).

Among other agents being tested in the treatment of RP are drugs that enhance nitric oxide availability—serotonin uptake blockers (e.g., fluoxetine), Rho-kinase inhibitors, local injection of botulinum toxin (Botox), antioxidants (acetylcysteine), angiotensin receptor blockers, and selective α2-adrenergic receptor antagonists. A combination of these agents, if tolerated, can be used in refractory cases. Various formulations of topical and oral nitroglycerin are employed.49,50 Although some degree of efficacy is obtained, use of nitroglycerin is limited by substantial side effects, including headache, dizziness, and local skin irritation. The cyclic guanine monophosphate phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are thought to be effective in the treatment of RP by sustaining the vasodilatory effect of nitric oxide.51,52 Studies using phosphodiesterase inhibitors have reported variable effects, and the ideal drug and dosing have not yet been defined. Despite the theoretical advantage of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, a study of quinapril showed that these medications did not affect the occurrence of digital ulcers or the frequency or severity of RP episodes.53 Thus, although ACEs are critical for the treatment of a scleroderma renal crisis (see renal section), they do not have a major role in the management of RP.

New emphasis is being placed on prevention of scleroderma vascular disease through the use of immunosuppressive and vasoprotective drugs. HMG-CoA (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A) reductase inhibitors (statins) can modify progression of vascular injury and can prevent vascular ischemia through different pleiotropic functions, as by improvement of endothelial dysfunction, reduction of clotting, and introduction of some anti-inflammatory effects.54,55 Data suggest that statins may increase the number of endothelial progenitor cells and may improve vascular remodeling after injury.56,57 In a randomized, placebo-controlled study of scleroderma patients with secondary RP, statin use significantly decreased the number of digital ulcers formed.58

Endothelin-1 is strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of RP and the vascular disease of scleroderma.59 Bosentan, an endothelin-1 receptor blocker, was studied in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicenter study that showed efficacy in preventing new digital ulcers, along with improved hand function, but it did not improve healing of existing ulcers compared with placebo.60

Sympathectomy is a viable option for patients with RP who are unresponsive to medical therapy; it should be considered as acute intervention during a critical ischemic event. Localized digital sympathectomy with lysis of fibrosis around the vessel is effective for acute ischemia and has mostly replaced cervical sympathectomy.61,62 Responses to sympathectomies suggest that the long-term benefit derived from these interventions is limited. In fact, Raynaud’s attacks eventually recur, and medical therapy is needed to prevent new events.

Careful assessment for correctable macrovascular disease should be done when confronted with acute digital ischemia, particularly when the whole finger is demarcated, or when the event involves a lower extremity. In this setting, appropriate studies such as arterial Doppler ultrasound or angiographic imaging are warranted. If macrovascular disease is present, vascular surgery may help to alleviate the occlusive process. Preferential involvement of the ulnar artery has been reported in scleroderma patients.63

Skin Involvement

The most overt clinical manifestation of scleroderma is skin disease. The degree of involvement can vary among patients, and involvement can change in severity and distribution over time in the same individual. Almost every scleroderma patient presents with skin thickening and hardening due to increased collagen and extracellular matrix deposition in the dermis. The distribution of skin changes is characteristic, with more frequent and intense involvement of fingers, hands, forearms, distal legs, feet, and face, and, to a lesser degree, the proximal limbs and anterior trunk. Sparing of the midback is typical. Scleroderma is classically subdivided into limited and diffuse cutaneous forms (Figure 84-7). Limited scleroderma is defined by skin thickening restricted to the face and limbs distally to the elbows and knees. Commonly, in this form of the disease, only the fingers and the face are involved. In contrast, diffuse cutaneous involvement is characterized by widespread skin thickening, including proximal limbs and truncal areas. Proximal skin involvement defines the diffuse cutaneous subset but may be absent in early stages of disease. Signs of skin thickening are not apparent in the setting of other disease manifestations (e.g., Raynaud’s phenomenon, nail-fold capillary abnormalities), nor is evidence of internal organ involvement. This clinical presentation is referred to as systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma. Traditionally, patients are clustered into limited and diffuse skin subsets, but evidence suggests the existence of an intermediate group of patients. Each subset of disease defined by the degree of skin thickening has a unique pattern of disease manifestation and risk for specific clinical outcomes. Therefore, expression of skin disease can be used as a predictor or a “clinical biomarker” of the disease course. The variable degree of skin involvement can be quantified by physical examination. The most widely accepted scoring system (modified Rodnan skin score) is applied by pinching the skin in 17 different body areas and subjectively averaging the thickness of each specific site from 0 = normal to 3 = very thick (Figure 84-8). The skin score (maximum, 51) is a useful clinical measurement tool that can be used to quantify the severity of skin disease.28 Although the overall extent of skin involvement as measured by the skin score can predict certain clinical outcomes, it does not define the quality of the skin process nor the level of disease activity at any single point in time. Therefore, it is important to follow the skin score over time and to measure changes sequentially to monitor disease progression.

Cutaneous involvement in scleroderma begins with clinical signs of inflammation. This is called the edematous phase because it is characterized by nonpitting edema of affected body areas. In limited scleroderma, this event is mild and is restricted to the digits; however, in the diffuse form of the disease, cutaneous swelling and edema can be widespread and so impressive in the limbs as to mimic a fluid overload state such as congestive heart failure. Edema can also cause local tissue compression. For example, upon involvement of the wrist area, scleroderma patients are not infrequently diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome (especially at disease onset) to explain hand and wrist discomfort. In association with edema, signs and symptoms of inflammation are common. Erythema of the skin and intense pruritus and pain (see Figure 84-7C) are characteristic of advancing active diffuse skin disease. This pain has a neuropathic quality with a reported “pins and needles” sensation. The disease process leads to loss of skin appendages, as well as decreased hair growth and loss of sweat and exocrine glands; thus the skin surface becomes dry and uncomfortable. Small papules can be seen in areas of trauma as the result of scratching, giving the surface a cobblestone texture. The edematous phase continues for several weeks but eventually gives way to a fibrotic stage, with protracted activity that may last months or years.

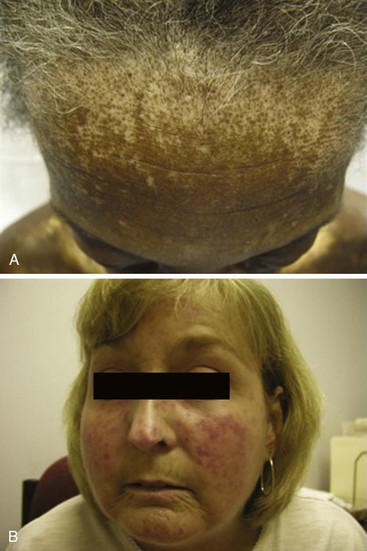

During the fibrotic phase, acute inflammation is clinically less obvious, and deposition in the dermis of excessive collagen and other extracellular material thickens the skin, making it inflexible and causing further loss of skin appendages. Fibrosis extends beyond the dermis into the deeper layers with loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue (lipodystrophy). In late stages of the disease, skin actually thins with atrophy and has a noninflammatory bound-down appearance. Deeper tissue fibrosis causes permanent contractures around joints or may involve underlying muscle, causing a myopathy (see Figure 84-7D). Patients with diffuse cutaneous scleroderma develop the most dramatic widespread skin changes; those with limited skin disease may note only puffy fingers and digital thickening typical of sclerodactyly. A masked facies, small oral and orbital apertures, and vertical furrowing of the perioral skin are consequences of skin and soft tissue fibrosis. In some patients, gum atrophy and facial skin tightening make the front teeth appear more prominent. Flexion contractures of fingers, wrists, and elbows often appear secondary to dermal sclerosis and fibrosis with atrophy of underlying tissues. Skin ulcers can develop as a complication of avascular fibrotic or damaged thinned skin and are very common at sites of trauma, such as over the digital metacarpophalangeal or proximal interphalangeal joints or at the tip of the elbows, particularly when joint contractures are present at these sites (see Figure 84-5). Ulcerations may be noted secondary to underlying vascular disease and tissue ischemia (see vascular disease section). Ankle or lower extremity ulcers occur rarely secondary to macrovascular occlusive disease or comorbid conditions (venous disease). Hypopigmentation (vitiligo-like) and/or hyperpigmentation of the skin (“salt-and-pepper” appearance) can develop typically on the face, arms, and trunk (Figure 84-9A). General tanning of the skin may be seen, even in the absence of sun exposure.

Telangiectasias are erythematous matted skin lesions of vascular origin; for this reason, they blanch on local pressure. They are composed of vasodilated postcapillary venules without evidence of inflammation and resemble the type of lesions seen in Osler-Weber-Rendu disease (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia). Telangiectasias develop primarily on the fingers, hands, face, and mucous membranes, but they may also be found on the limbs and trunk (Figure 84-9B). They tend to become more numerous over time in both limited and diffuse types of skin disease, and are more obvious in white patients with limited scleroderma. The biologic mechanism leading to the development of telangiectasias in scleroderma is thought to be related to the underlying chronic tissue hypoxia that stimulates abnormal secretion of vascular growth factors (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF]). Thus, the development of telangiectasias may indicate ongoing vascular injury and abnormal vascular repair or angiogenesis. The total burden of telangiectasias is associated with increased risk of pulmonary hypertension, suggesting that they are clinical biomarkers of systemic vascular disease. Nail-fold capillary abnormalities can be observed after immersion oil is applied to the skin surface at the base of the fingernails, and direct visualization is performed using an ophthalmoscope or by videocapillaroscopy. In early scleroderma, dilated capillary loops (giant capillaries) and microhemorrhages may be seen. At later stages, the nail-fold capillaries are attenuated and disorganized (see section on vascular changes).

Gastrointestinal Involvement

Key Points

Involvement of the upper GI tract is more common and can present with severe symptoms.

Dysfunction and failure of the lower GI tract are associated with poor prognosis.

Almost every scleroderma patient has symptoms of gastrointestinal disease, ranging from mild gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to severe bowel dysfunction, which can be life threatening. Virtually any segment of the gastrointestinal tract can be affected (Table 84-4).

Table 84-4 Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Scleroderma

| Site | Manifestation | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Oropharynx | ||

| Esophagus | ||

| Stomach | ||

| Small and large intestine | ||

| Anorectum |

Oropharynx

Patients may report that chewing is difficult because of decreased facial flexibility caused by skin and deeper tissue fibrosis. Perioral skin tightening can result in a decreased oral aperture and inability to open the mouth wide enough for proper dental care or to bite into large solid foods such as an apple (Figure 84-10). Dry membranes resulting from decreased saliva production can lead to difficult mastication. In some patients, periodontal disease and gum regression cause loosening of teeth, which further affects chewing capacity.

Upper pharyngeal function is usually normal, but a subset of patients may develop a myopathy that causes weakness of pharyngeal muscles, mimicking a neuromuscular disease.64 This manifestation is characterized by pharyngeal dysfunction with problems initiating swallowing and frequent coughing due to laryngeal penetration and can be associated with increased risk for aspiration of foods or liquids. Although limited pathologic studies of the upper pharyngeal structures have examined scleroderma, both myositis and fibrosis are known to occur.

Esophagus

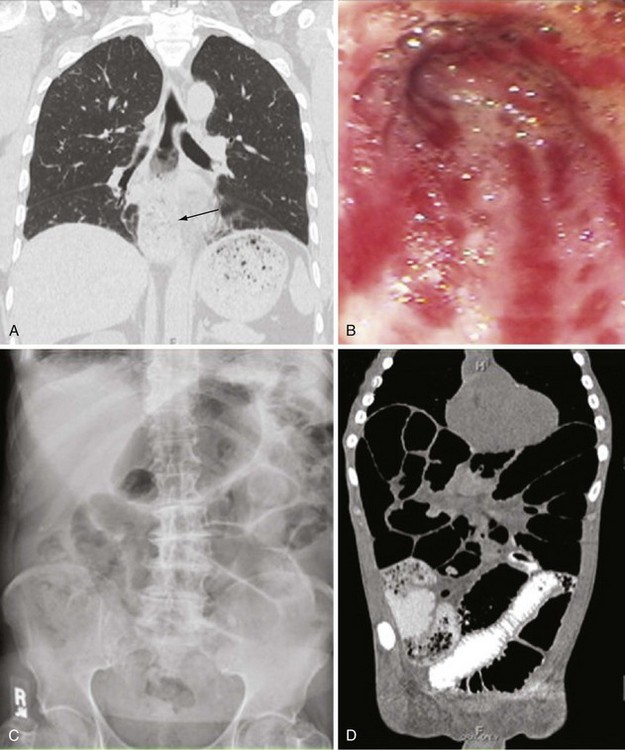

Dysphagia resulting from esophageal disease is the most common gastrointestinal symptom, occurring in approximately 90% of patients. Heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia for pills and solids (more than liquids) are the most common symptoms, but atypical retrosternal pain (particularly at night), periodic cough, a sense of food “sticking” in the esophagus, and nausea can result from esophageal dysfunction. Esophageal involvement in scleroderma is characterized by loss of normal smooth muscle function, especially in the lower two-thirds of the esophagus, and hypotonia of the lower esophageal sphincter (Figure 84-11A). Functional studies of esophageal motility suggest that neural dysfunction is common in patients with scleroderma, and that this may precede myopathic dysfunction and histologic changes in smooth muscle layers.65 Manometric evaluation has identified the presence of esophageal hypomotility in areas that later did not show any histologic abnormality of the smooth muscle. Other studies have shown esophageal smooth muscle activity in response to pharmacologic stimulation (methacholine challenge) early in the disease, but not in patients with more advanced scleroderma. The cause of these abnormalities is unknown, but clear evidence indicates that neural dysfunction precedes muscle disease.

Stomach

The degree of delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis) is underappreciated in scleroderma, and gastroparesis often causes early satiety, aggravation of GERD symptoms, anorexia, abdominal pain, a sensation of bloating, or nausea. Frequently, weight loss in scleroderma patients is a consequence of poor caloric intake due to lack of appetite from poor gastric function. Prokinetics are used to improve gastric emptying and related symptoms. Gastritis or gastric ulcer can occur. Dilation of the microvasculature in the gastric mucosa is found in a subset of patients. This manifestation, also called gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), is thought to be caused by an abnormal angiogenesis, leading to bizarre dilation of microvessels and arterial-venous (A-V) malformations similar to the telangiectasias seen in the skin, lips, and oral mucous membranes. In general, these lesions are asymptomatic, but they can be responsible for occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Extensive clusters of A-V malformations lead to the presence of longitudinal red stripes in the inner lining of the stomach, converging to the pylorus and described on endoscopy as “watermelon stomach,” based on their appearance (Figure 84-11B). Endoscopic therapy with laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy can be used to ablate bleeding vessels. Rarely, bleeding associated with GAVE is refractory and requires multiple transfusions, repeated laser or cryotherapy, or even gastric surgery (e.g., antral or gastric resection).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree