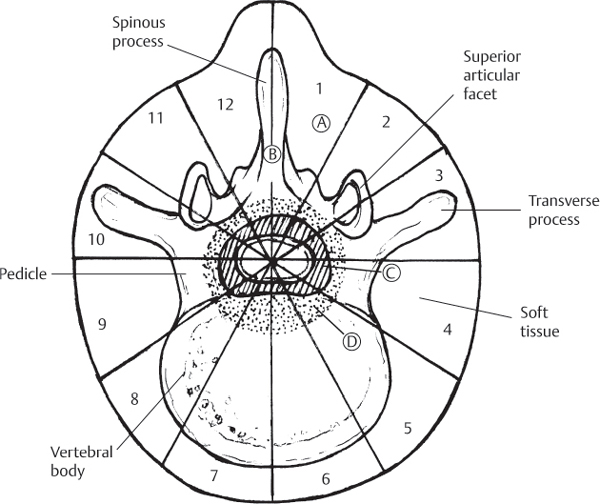

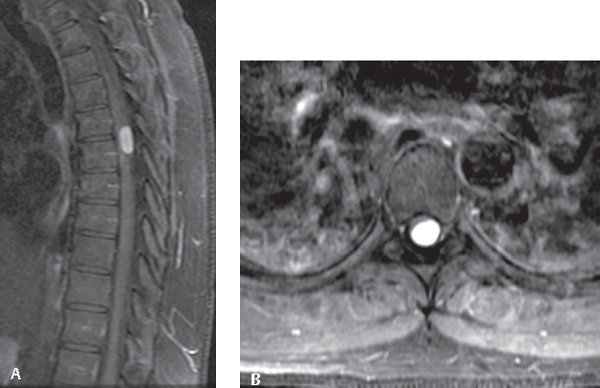

48 Tumors of the spine are relatively rare entities that affect only a small percentage of the population. They can, however, cause significant pain and neurologic compromise. Additionally, spinal metastasis, the most common spinal tumor, affects between 5% and 10% of cancer patients. In fact, ~ 50% of bony metastases involve the spine. The vertebral column is the most common site of spinal metastasis. The most common tumors that metastasize to bone include prostate, breast, lung, kidney, and thyroid. The simplest classification for spinal tumors is based on the location within the spine. Tumors can be classified as involving the bony spinal column, extradural space, intradural extramedullary region, or intradural intramedullary. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has greatly expanded the ability to place tumors in these categories. The most common presenting symptom of spinal tumors is pain. Most patients with metastatic tumors present with back pain weeks to months prior to developing neurologic symptoms. Two pain patterns are typically seen in these patients: tumor-related pain and mechanical pain. Tumor-related pain typically occurs at night or in the early morning, improves with activity, and responds to administration of steroids. This pain may be caused by inflammatory mediators or be related to expansion of the tumor, causing stretching of the periosteum. Mechanical pain results from structural problems, such as compression fractures. This pain is typically exacerbated with motion and does not respond to steroids. Other extradural spinal tumors, such as chordomas, osteoid osteoma, and aneurysmal bone cysts, also typically present with pain. The pain associated with osteoid osteomas is exquisitely responsive to aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Intradural extramedullary tumors, such as spinal meningiomas (Fig. 48.1) and nerve sheath tumors, also present with local pain. Patients with spinal nerve sheath tumors frequently have symptoms related to the affected nerve root (i.e., radiculopathy). Less often, these tumors cause gait dysfunction, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and other symptoms of myelopathy. Intradural intramedullary tumors, such as spinal ependymomas and astrocytomas, also tend to present with pain. Initially this is local, but it can also radiate elsewhere. Later-stage symptoms include myelopathy and, for filum terminale ependymomas, motor weakness and sphincter dysfunction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with and without gadolinium administration, of the whole spine is the imaging modality of choice for initial diagnosis of all spinal tumors (Fig. 48.2). In the presence of known metastatic disease, it may be all that is required for workup. Consider myelography if other imaging modalities are contraindicated or inadequate. Other useful imaging modalities include nuclear medicine bone scans (technetium-99) for workup of metastatic disease, computed tomography (CT), and plain radiographs for assessment of bony involvement for extradural lesions and assessment of spinal stability. Many primary bony tumors have distinct appearances on plain radiographs; thus, it is essential to obtain these imaging studies when bone involvement is suspected. Fig. 48.1 Surgical staging. The location of the lesion using this scheme is useful for surgical planning prior to tumor excision. Fig. 48.2 MRI images, post contrast infusion, showing homogeneously enhancing intradural extramedullary meningioma compressing the spinal cord. (A) T1 sagittal. (B) Axial. Though bone scans are more sensitive than plain radiographs in the detection of metastatic disease, they rely on osteoblastic reaction or bone deposition to detect metastatic disease. Thus, they may miss rapidly growing tumors and are insensitive for multiple myeloma and tumors of the bone marrow. Additionally, they are nonspecific and may also detect fractures, benign spinal tumors, and degenerative changes. Bone scans are most useful to screen the entire skeleton for evidence of metastatic disease. In cases of suspected metastatic disease, CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis may reveal a primary lesion. Needle biopsy is often useful to obtain an initial diagnosis in the case of extradural lesions. Especially when considering surgery, angiography should be considered for preoperative embolization of vascular tumors (renal cell, thyroid, aneurysmal bone cysts, etc.) to minimize operative blood loss. Staging is commonly used for primary tumors of the spinal column, such as sarcomas. Enneking proposed an oncologic staging system for musculoskeletal tumors that can be used for bony spinal column tumors. This system uses both radiologic and clinical data and presents two systems: one for benign tumors and the other for malignant tumors (Table 48.1). Table 48.1 Enneking Staging System for Tumors of the Osseous Spine

Classification, Staging, and Management of Spinal Tumors

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

Spinal Imaging

![]() Staging

Staging

Benign tumors | |

S1 | Latent, inactive tumor: usually asymptomatic and bordered by a true capsule; often no management is required |

S2 | Slow-growing, resulting in mild symptoms; thin capsule and reactive tissue; usually an intralesional excision can be performed with a low rate of recurrence |

S3 | Rapidly growing tumors where the capsule is very thin or absent; en bloc excision is usually appropriate management |

Malignant tumors | |

IA | Low-grade malignant tumor confined to vertebrae |

IB | Low-grade malignant tumor invading paravertebral compartments |

IIA | High-grade malignant tumor |

IIB | High-grade malignant tumor with infiltrating tumor spread beyond the cortical border with no gross destruction; often there is invasion of the epidural space |

IIIA | High-grade malignant tumor with distant metastasis |

IIIB | High-grade malignant tumor with infiltrating tumor spread beyond the cortical border with no gross destruction, with distant metastases |

Another scheme for surgical staging divides the transverse plane of the vertebra into 12 radiating zones, with five layers each (Fig. 48.1). The tumor’s longitudinal extent is calculated from the number of vertebral segments involved. MRI, CT, and even angiography may be useful in describing the transverse and longitudinal involvement of the tumor. This system may prove very useful in planning the surgical resection.

Treatment

Treatment

Pharmacological and Minimally Invasive Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree