87 Classification and Epidemiology of Systemic Vasculitis

Classification

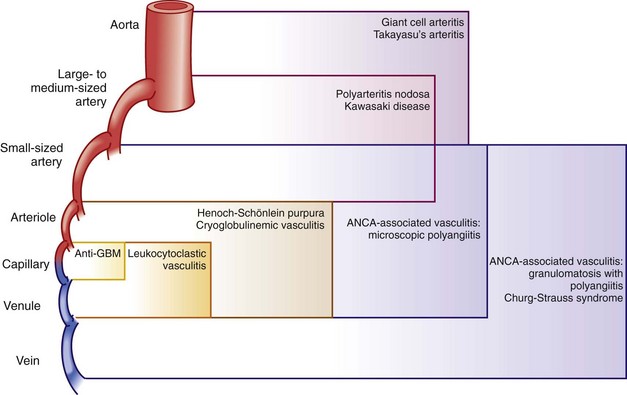

Few disorders in medicine are more challenging in diagnosis and treatment than the systemic vasculitides. These heterogeneous disorders are linked by the common finding of destructive inflammation within the walls of blood vessels. Current classification schemes recognize approximately 20 primary forms of vasculitis and several major categories of secondary vasculitis (e.g., other rheumatologic diseases, malignancy, infection) (Table 87-1). Over the past half century, numerous comprehensive classification schemes have been attempted.1 No attempt has been entirely satisfactory because understanding of these conditions continues to evolve. All vasculitis classification schemes are works in progress, susceptible to change as new information emerges.

Table 87-1 Classification Scheme of Vasculitides According to Size of Predominant Blood Vessels Involved

| Primary Vasculitides |

| Predominantly Large Vessel Vasculitides |

| Predominantly Medium Vessel Vasculitides |

| Predominantly Small Vessel Vasculitides |

| Secondary Forms of Vasculitis |

| Miscellaneous Small Vessel Vasculitides |

Connective tissue disorders‡ (rheumatoid vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, inflammatory myopathies) |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

* May involve small, medium, and large blood vessels.

† Immune complexes formed in situ, in contrast to other forms of immune complex–mediated vasculitis.

‡ Frequent overlap of small and medium blood vessel involvement.

§ Not all forms of these disorders are always associated with ANCA.

Current classification schemes are understood best in light of their nosologic predecessors. The first “modern” case of systemic vasculitis was recognized in the 1860s by Kussmaul and Maier.2 That case, which involved medium-sized, muscular arteries, has served as the reference point for classifying many subsequently recognized forms of vasculitis. Because of the importance of that first report in the understanding and classification of vasculitis, the case is described in detail here.

First Modern Case: “Periarteritis Nodosa”

In 1866 Kussmaul and Maier reported the case of a 27-year-old tailor who died during a month-long hospital stay.2,3 On presentation, the patient was strong enough to climb two flights of stairs to the clinic but “afterward felt so weak that he immediately had to go to bed.” He complained of numbness on the volar aspect of his thumb and the two neighboring fingers on the right hand. Over the ensuing days, “the general weakness increased so rapidly that he was unable to leave the bed, [and] the feeling of numbness also appeared in the left hand.” Muscle paralysis progressed quickly: “Before our eyes, a young man developed a general paralysis of the voluntary muscles … [He] had to be fed by attendants, and within a few weeks was robbed of the use of most of his muscles.”2,3

The patient’s weakness, caused by vasculitic neuropathy (mononeuritis multiplex), was accompanied by tachycardia, abdominal pains, and the appearance of cutaneous nodules over his trunk. His death was described as follows: “He was scarcely able to speak, lay with persistent severe abdominal and muscle pains, opisthotonically stretched, whimpering, and begged the doctors not to leave him … Death occurred … at 2 o’clock in the morning.” At autopsy, grossly visible nodules were present along the patient’s medium-sized arteries. Kussmaul and Maier2 suggested the name “periarteritis nodosa” for this disease because of the apparent localization of inflammation to the perivascular sheaths and outer layers of the arterial walls, leading to nodular thickening of the vessels. The name was later revised to polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), to reflect the widespread arterial involvement of this disease and the fact that inflammation in PAN extends through the entire thickness of the vessel wall.4,5

Polyarteritis Nodosa as a Reference Point

• The general confinement of the disease to medium-sized vessels* as opposed to capillaries and postcapillary venules (small vessels) and the aorta and its major branches (large vessels)

• The exclusive involvement of arteries, with sparing of veins

• The tendency to form microaneurysms

• The absence of lung involvement

• The lack of granulomatous inflammation

• The absence of associated autoantibodies (e.g., antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCAs], anti–glomerular basement membrane [anti-GBM] antibodies, or rheumatoid factor)

• The association of some cases with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection

Classification by Vessel Size

Because the etiologies of most forms of vasculitis are unknown, the most valid basis for classifying the vasculitides is the size of the predominant blood vessels involved. Under such classification schemes, the vasculitides are categorized initially by whether the vessels affected are large, medium, or small (see Table 87-1 and Figure 87-1). “Large” generally denotes the aorta and its major branches (and the corresponding vessels in the venous circulation in some forms of vasculitis, e.g., Behçet’s disease). “Medium” refers to vessels that are smaller than the major aortic branches yet still large enough to contain four elements: (1) an intima, (2) a continuous internal elastic lamina, (3) a muscular media, and (4) an adventitia. In clinical terms, medium vessel vasculitis (see Table 87-1) is generally macrovascular (i.e., involves vessels large enough to be observed in gross pathologic specimens or visualized by angiography). “Small vessel” vasculitis, which incorporates all vessels below macroscopic disease, includes capillaries, postcapillary venules, and arterioles. Such vessels all are typically less than 500 µm in outer diameter. Because glomeruli may be viewed simply as differentiated capillaries, forms of vasculitis that cause glomerulonephritis are considered to be small vessel vasculitides. Table 87-2 presents the typical clinical manifestations associated with small, medium, and large vessel vasculitides.

Table 87-2 Typical Clinical Manifestations of Large, Medium, and Small Vessel Involvement by Vasculitis

| Large | Medium | Small |

|---|---|---|

Constitutional symptoms: fever, weight loss, malaise, arthralgias/arthritis (common to vasculitides of all vessel sizes)

Additional Considerations in Classification

Many other considerations are important in the classification of vasculitis (Table 87-3): (1) the patient’s demographic profile (see Epidemiology section), (2) the disease’s tropism for particular organs, (3) the presence or absence of granulomatous inflammation, (4) the participation of immune complexes in disease pathophysiology, (5) the finding of characteristic autoantibodies in the patients’ serum (e.g., ANCAs, anti-GBM antibodies, or rheumatoid factor), and (6) the detection of certain infections known to cause specific forms of vasculitis.

Table 87-3 Considerations in the Classifications of Systemic Vasculitis

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; GBM, glomerular basement membrane.

The granulomatous features of some forms of vasculitis resemble chronic infections (e.g., infections caused by fungi or mycobacteria) or the inflammation induced by the presence of a foreign body. Granulomatous inflammation is more likely to be found in some organs (e.g., the lung) than in others (e.g., the kidney or skin). Some patients without evidence of granulomatous inflammation at early points in their courses later exhibit such features as their diseases unfold. Patients initially diagnosed with cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis or microscopic polyangiitis may be reclassified as having GPA if disease manifestations appear in new organs and granulomatous inflammation is found on biopsy specimens. Table 87-4 presents forms of vasculitis commonly associated with granulomatous inflammation.

Table 87-4 Forms of Vasculitis Associated with Granulomatous Inflammation

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|