Fig. 1

Diagram of the pubic symphysis demonstrating the midline fibrocartilage disk in red and the anteroinferior arcuate ligament in green. Reproduced with permission from Springer [17]

The pubic symphysis acts as a fulcrum for forces generated at the anterior pelvis (Fig. 2). Musculoaponeurotic plate attachments at the pubic symphysis are important for core stability, and coordinated contraction of the muscles that directly attach to the fulcrum produces a slight anterior tilt of the pelvis. The abdominal muscle attachments include the rectus abdominis, internal oblique, external oblique, and transversus abdominis. The medial thigh compartment attachments include the pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, and gracilis. Functionally, the most important attachments for anterior pelvis stabilization are where the rectus abdominis and the three adductor muscles join to the fibrocartilage plate of the pubic symphysis [10, 13, 14]. The rectus abdominis attaches to the anterior and anterior–inferior aspects of the pubic symphysis. The origin of the pectineus and adductors is confluent with the rectus insertion and is defined as the rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis [14].

Fig. 2

Diagram of forces generated at the anterior pelvis that have to be counterbalanced by the pubic symphysis. Reproduced with permission from Springer[14]

The abdominal wall has a layered structure. From superficial to deep, the structures of the abdominal wall are skin, fascia, external oblique fascia and muscle, internal oblique fascia and muscle, transversus abdominis muscle and fascia, and the transversalis fascia. The posterior fascia is deficient in the lower 1/3 of the rectus, so descriptions of tears of the posterior sheath in this region are not accurate. Fibers from the rectus, conjoint tendon (fusion of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis fascia), and external oblique merge to form the pubic aponeurosis which is confluent with the adductor and gracilis origin. The conjoint tendon inserts anterior to the rectus abdominis on the pubis [15].

During core rotation and extension, the rectus abdominis and the adductor longus act as antagonists (Fig. 3). The rectus elevates the pelvis while the adductor depresses it. Injuring one of the components tends to cause abnormal biomechanical forces on opposing muscles and tendons leading to further injury at the aponeurosis and the tenoperiosteal attachments [16]. Detachment of the aponeurosis itself can lead to instability of the pubic symphysis, as injury to the arcuate or anterior pubic ligaments. Altering the biomechanics of the core may subsequently lead to abnormal forces throughout the upper and lower extremities that may ultimately lead to aggravation of hip impingement, labral tears, knee ligament injuries, and even ankle sprains [17].

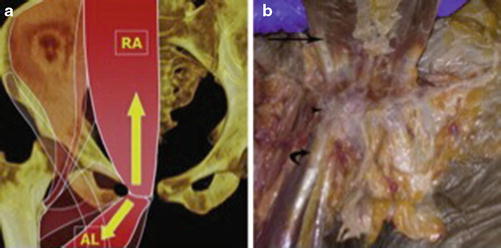

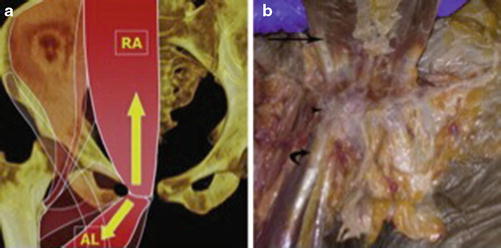

Fig. 3

(a) Diagram of the opposing forces of the rectus abdominis (RA) and adductor longus (AL) at the pubic tubercle. The rectus abdominis creates superoposterior tension, whereas the adductor longus creates inferoanterior tension. Disruption of either leads to altered biomechanics. The black circle represents the superficial inguinal ring. (b) Gross specimen demonstrates the rectus abdominis (arrow), adductor longus (curved arrow), and the pubic tubercle attachment of the rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis (arrowhead). Reproduced with permission from Springer [17]

Disorders with innervation of the anterior pelvis may also be a pain generator that can present as groin pain. In particular, pain may be caused by nerve entrapment of the genital branches of the ilioinguinal or genitofemoral nerves due to weakness in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal [18]. The symphysis itself is innervated by branches of the pudendal and genitofemoral nerves [13]. Other reports have suggested that the iliohypogastric or obturator nerves could also be involved [19].

It should be noted that there are differences in male versus female anatomy with regard to the pelvis and the hips. Historically, <1 % of patients with athletic pubalgia were female as reported by Meyers, but this has changed dramatically over the last two decades, and now approximately 15 % of patients with athletic pubalgia are female [20]. Differences in anatomy include a more slender and lighter pelvis in the female with fewer shifts in forces, a relatively wider subpubic angle leading to a different distribution of forces, and a relatively wider, more stable pelvis resulting in the transfer of destabilizing forces to the narrow-based lower extremities (Fig. 4) [4]. These anatomic differences are likely responsible for the difference in injury incidence in males compared to females. The forces are likely protective with regard to development of athletic pubalgia, but may also contribute to the increased incidence of anterior cruciate injuries in women [1].

Fig. 4

Basic differences in male versus the female anatomy that relate to the pubic joint and injury. Note the differences in width between the pelvis and knees of the two genders. These differences suggest a different distribution of forces during extremes of exertion, for example, more lateral forces emanate from the female pelvis and more acutely angled forces are transmitted to female knees during landing. Reproduced with permission from Springer [4]

History of Groin Injury

Reports of groin injuries have appeared in the medical literature as early as 1932 when Spinelli reported on pubic pain in fencers [21]. In 1966, Cabot reported on Spanish soccer players with groin pain [22]. In 1980 Gilmore recognized and surgically repaired groin disruption in a group of athletes with chronic lower abdominal and groin pain. He identified a triad of pathology including injuries to the external oblique aponeurosis and conjoint tendon, avulsion of the conjoint tendon from the pubic tubercle, and dehiscence of the conjoint tendon from the inguinal ligament [2]. This entity of groin disruption associated with groin pain in the athlete was subsequently termed Gilmore’s groin. A traditional hernia was not identified in this series of patients. Gilmore later presented a larger series of patients in which he described an anatomical repair of the injured structures with a six-layer suture repair. He reported a 97 % return to sport rate with this technique [5].

In 1993 the term “sports hernia” was first coined by Hackney to describe a syndrome of groin pain in athletes that had failed nonsurgical management. During surgery, he identified weakening of the transversalis fascia with separation of that fascia from the conjoint tendon, dilation of the inguinal ring, and one case of a small direct hernia. He treated all patients with a surgical repair of the posterior inguinal wall and obtained an 87 % return to sport rate in 15 athletes [12].

In 2001 Irshad et al. described the “hockey groin syndrome” in 22 National Hockey League players and found tearing of the external oblique aponeurosis and entrapment of the ilioinguinal nerve. Surgical management included mesh repair of the external oblique aponeurosis and ablation of the ilioinguinal nerve [23].

Meyers has proposed that use of the term “athletic pubalgia,” and more recently “Core injury,” is more appropriate for the constellation of injuries to the abdominal wall, hip flexors, adductors, and pubic symphysis than the more commonly used “sports hernia” [4]. He introduced the idea of a “pubic joint” as a complex structure consisting of the anterior pelvic ring and associated musculotendinous attachments. He proposed that the primary pathology in athletic pubalgia is an imbalance between the strong adductors and the relatively weak abdominal muscles, which are then predisposed to strain during the abdominal hyperextension/hip abduction mechanism that is commonly associated with the onset of groin pain in athletes. Based on findings at surgery, Meyers describes 17 different variants of athletic pubalgia, the most common of which are multiple tears or detachment of the anterior and anterolateral fibers of the rectus abdominis from the pubis and combined injuries to the rectus and adductors [20].

As the understanding of intra-articular hip pathology has improved, there has been increasing recognition of labral pathology and femoroacetabular impingement coexisting with athletic pubalgia [9, 10]. Larson et al. reported surgical treatment in a subset of athletes with coexistent femoroacetabular impingement and athletic pubalgia. Failure to treat both pathologies resulted in a low return to sport rate (25 % of athletic pubalgia was addressed in isolation, and 50 % of the intra-articular hip pathology was addressed in isolation). This resulted in the development of a surgical protocol to address both etiologies under the same anesthesia when athletes present with both symptomatic athletic pubalgia and intra-articular hip disorders (FAI). Using this approach, they achieved an 85–93 % return to sport rate [9].

Presentation

Groin injuries are most common in athletes who participate in sports that require repetitive twisting, pivoting, and cutting motions, as well as activities requiring frequent acceleration and deceleration. Ice hockey, soccer, and rugby have a particularly high incidence [2, 23, 24]. Up to 13 % of soccer injuries involve the groin, and in one series, 58 % of soccer players have experienced a groin injury [25].

Patients with an isolated sports hernia usually present with a dull, chronic pain in the groin. Occasionally the pain radiates to the perineum, inner thigh, or occasionally the scrotum. They generally report an insidious onset of groin pain that intensifies with athletic activity and is relieved with rest [1, 8, 26–28]. Pain is usually most aggravated during sudden acceleration, twisting and turning, pivoting, cutting, kicking, sit-ups, coughing, or sneezing [8, 24, 27, 28]. Meyers et al. found that 92 % of their athletes had minimal to no pain at rest and 100 % reported pain with exertion [8]. Night pain that awakens the athlete from sleep and severe rest pain are atypical and should raise concern for tumors and other nonmusculoskeletal pathology.

Usually groin pain starts unilaterally, but 43 % of patients developed bilateral symptoms. Sixty-seven percent developed adductor pain after the onset of lower abdominal pain [9].

Some patients remember a specific instance when the pain began; however, others do not recall one particular event. There is some discrepancy within the literature regarding the acuity of presentation, with 6–71 % of athletes recalling an inciting event [7, 8, 29]. If an inciting event occurs, two types of pain syndrome may emerge: (1) The patient is unable to participate in sport after the first 5 min of exertion due to incapacitating pain and despite conservative care and rehabilitation remains disabled, or (2) the athlete can play through the pain, but often at less than 100 % capacity. At the conclusion of the season, the athlete may rest for a few months and anticipate resolution of the pain. Often, however, upon returning to training, they note recurrence of pubalgia symptoms [1].

Physical Examination

After a thorough history, a comprehensive physical examination is required to distinguish between intra-articular and extra-articular hip pathology. This will help dictate the next most appropriate workup with regard to imaging studies.

Assessment for athletic pubalgia should begin with palpation of the pubic symphysis , insertion of the rectus abdominis, adductor origin, external and internal obliques, transverses abdominis, pectineus, gracilis, and inguinal ring for areas of tenderness. Upon palpation, there is no detectable true inguinal hernia; however, there is typically tenderness to palpation of the conjoint tendon and sometimes the pubic tubercle (22 %), adductor longus (36 %), superficial inguinal ring, or posterior inguinal canal [8, 30, 31]. Pain can be elicited with provocative testing such as with simulated coughing, resisted sit-ups (46 %), and resisted hip adduction or Valsalva [8]. One study found that more patients had pain with resisted adduction (88 %) than pubic tenderness (22 %) [8]. Patients can also have pain with resisted hip flexion (9 %) [8, 27].

Kachingwe and Grech noted five signs and symptoms that they felt most indicative of a sports hernia. These include (1) a subjective complaint of deep groin/lower abdominal pain; (2) exacerbation of the pain with sport-specific sprinting, kicking, cutting, and/or sit-ups and relief of pain with rest; (3) palpable tenderness over the pubic ramus at the insertion of the rectus abdominis and/or conjoined tendon; (4) pain with resisted hip adduction at 0°, 45° and/or 90° of hip flexion; and (5) pain with resisted abdominal curl up [27].

It is important to rule out intra-articular hip pathology with a thorough physical exam of the hip including hip range of motion (flexion, extension, adduction, and abduction), internal and external rotation, and provocative testing to assess for femoroacetabular impingement. Typically, the anterior impingement test (flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) or FADIR test is performed which can suggest intra-articular hip pathology [32]. Palpation of the insertion of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus, short external rotators, and trochanteric bursa should be performed as well, and a lower extremity neurologic exam and straight leg raise may be useful to rule out lumbar spine pathology.

Imaging

Radiographic Analysis

Plain radiographs are recommended for the initial evaluation of the athlete with hip or groin pain. Although they cannot specifically identify athletic pubalgia, they are excellent at visualizing and ruling out other pathologies including osteitis pubis, avulsion fractures, stress fractures, apophysitis, osteoarthritis, and femoroacetabular impingement/ dysplasia. It is important to obtain good quality, properly oriented images according to an established imaging protocol. The initial series should include an anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph, a modified Dunn, or elongated neck lateral [33, 34].

The AP view may be used to evaluate the pubic symphysis for evidence of osteitis pubis, including sclerosis, fragmentation, and cyst formation within the pubic ramus, as well as symphyseal widening. When evaluating for femoroacetabular impingement, femoral head neck deformities and acetabular depth and version are assessed utilizing the alpha angle, femoral head/neck offset, neck shaft angle, lateral center edge angle (LCE), anterior center edge angle (ACE), Tonnis angle, and presence of a crossover sign. In the adolescent athlete, the AP view can be useful to identify apophyseal injuries. Occasionally, stress fractures of the femoral neck and pubic rami and sacroiliitis may be identified if they are well established [15].

Stability of the pubic symphysis can be determined on single leg stance AP views. Symphyseal widening greater than 7 mm or vertical translation greater than 2 mm on a single leg stance view suggests instability of the pubic symphysis [35].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

While plain x-rays and CT scans can be helpful to rule out bony abnormalities, magnetic resonance imaging plays a critical role in the accurate diagnosis of core injuries of the abdominal musculature in the pelvic region.

A dedicated athletic pubalgia MRI protocol has evolved as the imaging standard for core muscle injuries, particularly if the pathology is felt to be extrinsic to the hip joint. It includes large field-of-view sequences of the bony pelvis as well as smaller field-of-view sequences of the pubic symphysis [36]. Meyers et al. have put forth such a specific technique for MRI evaluation of sports hernia, which correlates well with demonstrable injury [17]. This technique uses a surface coil, a send–receive body coil, as well as oblique planes to maximize the evaluation of the osseous and musculotendinous pathology of the pelvis [20]. If the radiologist is unfamiliar with such a protocol, guidance can be found in multiple published reviews [16, 36].

Ideally, coronal oblique and axial oblique sequences through the rectus insertion and pubic symphysis should be obtained in addition to standard sagittal, coronal, and axial sequences. Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) and proton density fat-suppression imaging are useful in identifying bone and soft tissue edema [37]. MRI is 68 % sensitive and 100 % specific for rectus abdominis pathology when compared with findings at surgery and 86 % sensitive and 89 % specific for adductor pathology. It is 100 % sensitive for osteitis pubis [16]. Non-arthrogram studies may be preferred for in-season athletes to avoid the potential for irritation secondary to intra-articular contrast administration.

The MRI should be evaluated in a systematic fashion. Working in a systematic fashion can help identify not only injuries related to athletic pubalgia but other etiologies of groin pain as well including pelvic muscle strains and tears, osteitis pubis, fracture, sacroiliitis, visceral pathology, and intrinsic hip pathology.

When suspecting athletic pubalgia clinically, the rectus abdominis/adductor longus aponeurosis injuries are the most commonly encountered lesions on MRI. The injury generally involves the caudal aspect of the rectus abdominis insertion, the adductor longus origin, and the pubic tubercle periosteum [14, 16, 20]. Frequently, interstitial tearing of the lateral aspect of the caudal rectus abdominis can be seen, with occasional involvement of the adductor longus tendon (Fig. 5). The injury is usually unilateral and does not extend across the midline. Edema in the anteroinferior aspect of the superior pubic ramus is most consistent with injury to the common adductor–rectus aponeurosis. Frequent findings include fluid signal within the rectus abdominis or adductor insertion, thickening of either structure, peritendinous fluid, or partial or complete disruption of either tendon. Most commonly, there is confluent fluid signal extending from the anterior–inferior insertion of the rectus abdominis into the adductor origin, with corresponding fluid signal in the pubis (Figs. 6, 7, and 8) [16].

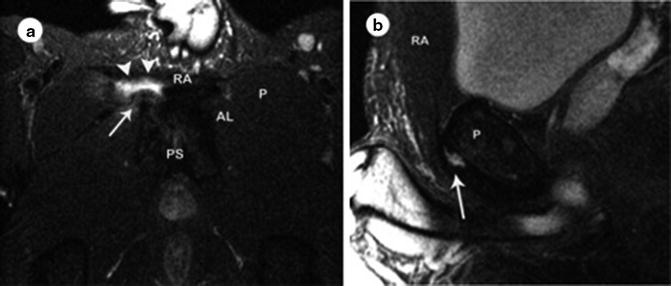

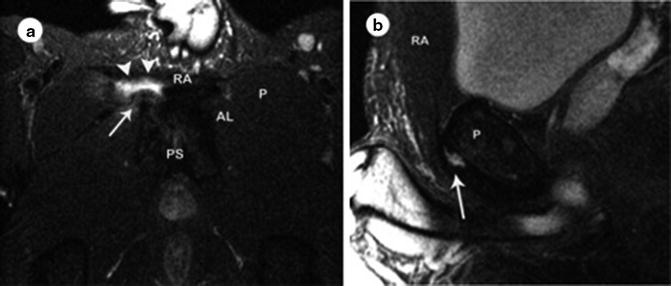

Fig. 5

Axial (a) and sagittal (b): T2-weighted fast spin echo fat suppressed images from a noncontrast MRI dedicated to the pelvis using an athletic pubalgia protocol acquired at 1.5 T in a professional football player with refractory right-sided groin pain: on the axial image, the left rectus abdominis (RA), pectineus (P), and adductor longus (AL) are intact, and the pubic symphysis (PS) is normal. On the right, the rectus abdominis is amputated (arrowheads) and the adductor longus is retracted (arrow). On the sagittal image, the rectus abdominis is disrupted at its anteroinferior pubic attachment (arrow). On this lateral representation of anatomy one cm lateral to the pubic symphysis, “P” denotes the pubic bone and “RA” the rectus abdominis muscle. Reproduced with permission from Springer [4]

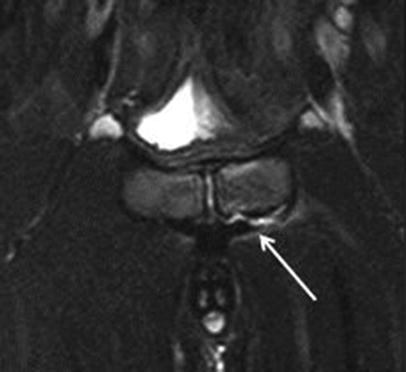

Fig. 6

Oblique axial fat-suppression T2 MRI of the pubic symphysis. There is disruption of the left rectus aponeurosis as it inserts on the anterior aspect of the superior pubic ramus (tip of the white arrow). Reproduced with permission from Springer

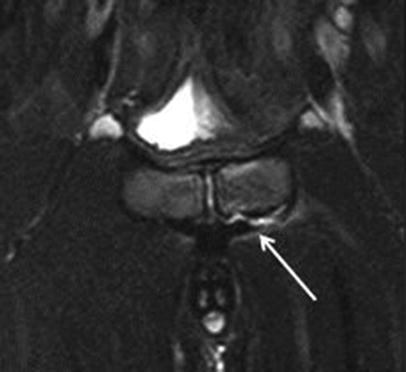

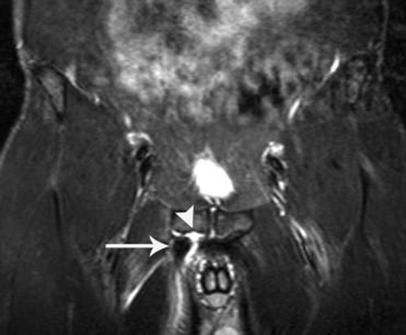

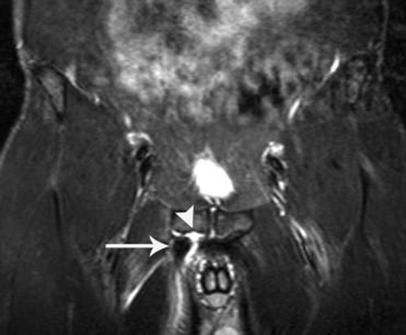

Fig. 7

Coronal short tau inversion recovery image of the pelvis acquired at 1.5 T using an athletic pubalgia protocol in a professional baseball player with an acute right-sided groin injury while fielding a bunt: The brightest signal represents fluid on this fluid-sensitive sequence. Note the abnormal fluid signal tracking inferolaterally from the pubic symphysis (arrowhead), sometimes referred to as a secondary cleft sign and often indicating a tear at the rectus abdominis attachment on the pubic bone. The adductor longus tendon has been avulsed and is retracted caudally and laterally (arrow). Reproduced with permission from Springer [4]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree