Phase I

Mild pain after exercise lasting <24 h

Phase II

Pain after exercise lasting >48 h and resolving with warm-up

Phase III

Pain with exercise, does not alter activity

Phase IV

Pain with exercise that alters activity

Phase V

Pain caused by heavy activities of daily living

Phase VI

Intermittent pain at rest that does not disturb sleep; pain caused by light activities of daily living

Phase VII

Constant rest pain and pain that disturbs sleep

Stage I | Temporary irritation |

Stage II | Permanent tendinosis; less than 50 % tendon cross section |

Stage III | Permanent tendinosis; greater than 50 % tendon cross section |

Stage IV | Partial or total rupture of tendon |

26.3 Clinical Presentation and Essential Physical Exam

Patients with tennis elbow typically present in the fifth and sixth decades and often with a history of overuse injury and a high activity level. Men and women appear to be affected equally; manual laborers, especially those working with vibratory tools or requiring excessive gripping forces, are particularly at risk [4, 16]. A history of insidious onset of activity-related, lateral elbow pain is often elicited. The pain may occasionally radiate into the forearm. Symptoms may progress to grip strength weakness or difficulty with activities of daily living such as shaving, shaking hands, lifting grocery bags, or raising a coffee mug. A common complaint is pain while reaching to grab a handbag, groceries, or a briefcase from the backseat of a car.

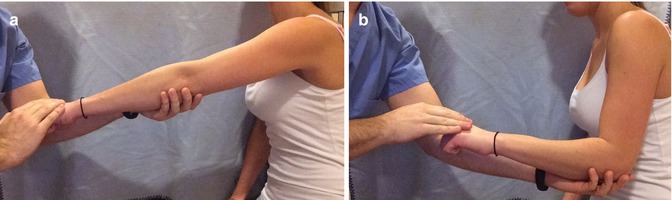

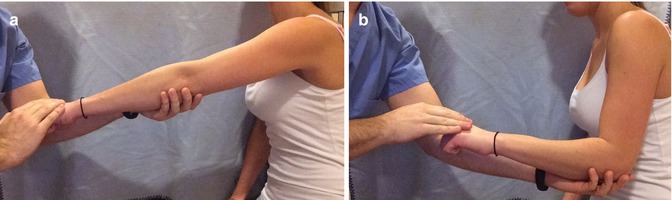

Inspection of the lateral elbow may reveal mild swelling around a point of maximal tenderness, which is approximately 1 cm distal and anterior to the lateral epicondyle. Resisted wrist and long finger extension while the elbow is extended are generally provocative; reproduction of pain with these maneuvers while the elbow is flexed usually heralds more severe disease (Fig. 26.1a, b). The “chair test” is an additional provocative maneuver, which is considered positive when pain is elicited in the lateral elbow while the patient lifts the back of a chair with a pronated hand (Fig. 26.2) [17]. Elbow range of motion is generally preserved, and significant swelling is unusual.

Fig. 26.1

(a, b) The patient actively extends the wrist against resistance with the elbows extended (a) and flexed (b). A positive test elicits pain over the lateral elbow. In mild disease, pain may not be present with the elbows flexed; if pain is present, it usually heralds more severe disease

Fig. 26.2

Chair test. The patient holds the back of a chair with the arm extended and hand pronated. Reproduction of pain over the lateral epicondyle with an attempt to raise the chair is considered a positive test

Other causes of lateral elbow pain should be excluded; radicular pain from the neck, crepitus or clicking with elbow range of motion, and significant weakness of wrist extension are characteristic of other disorders (Table 26.3).

Table 26.3

Differential diagnosis of lateral elbow pain

Pathology | History | Physical exam | Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|

Cervical spondylosis | Radicular pain into the elbow | Symptoms with spine compression/extension | XR + MRI of C-spine |

Neck pain | |||

Radial tunnel syndrome | Insidious onset of lateral elbow pain | Pain 2–4 cm distal to epicondyle | EMG + NCSa |

PIN compression | Insidious onset of lateral elbow pain and weakness | Weakness of the wrist and finger extensors | EMG + NCS |

Intra-articular loose bodies | Trauma | Clicking or limitation of range of motion | XR of the elbow |

Weight lifting | |||

Chondral lesions | Trauma | Clicking or limitation of range of motion | MRI of the elbow |

Weight lifting | |||

Tumors | Prior malignancy, night pain, constitutional symptoms | Palpable mass | XR + MRI of the elbow |

Avascular necrosis | Sickle cell anemia, alcohol abuse, HIV, corticosteroids | Joint effusion, mechanical symptoms | XR + MRI of the elbow |

Osteochondritis dissecans | Adolescent patients, gymnasts, throwers | Joint effusion, mechanical symptoms | XR of the elbow |

26.4 Essential Radiology

While lateral epicondylitis is principally a clinical diagnosis, standard elbow radiographs are typically obtained to exclude other pathology about the elbow. Typically plain film x-rays are normal, although findings consistent with soft tissue calcification or epicondylar exostosis are not uncommon [15]. Other studies such as ultrasound, MRI, and EMG may be useful for excluding other conditions, particularly in patients with atypical presentation.

Doppler ultrasonography as well as grayscale ultrasound may be utilized to visualize tendon tears, thinning, thickening, calcification, neovascularization, lateral collateral ligament damage, and lateral epicondyle irregularities. Ultrasound is less sensitive but equally as specific as MRI with reported sensitivity and specificity at 72–88 % and 36–100 %, respectively [18, 19]. Interestingly, Clarke et al. demonstrated that patients with ultrasound findings of large intrasubstance tendon tears and/or associated lateral collateral ligament tears were less likely to respond to nonoperative therapy [20].

Magnetic resonance imaging is seldom needed for diagnosing lateral epicondylitis. Images may show increased signal intensity around the extensor origin with varying degrees of tendon tearing, but the intensity of these findings has not been reliably correlated to the severity of the patient’s symptoms [21]. In general, this modality is reserved for identifying intra-articular pathology.

26.5 Disease-Specific Clinical and Arthroscopic Pathology

Nirschl and Pettrone described gross specimens of the ECRB in patients with tennis elbow as “grayish, immature scar tissue which appears shiny, edematous, and friable.” Their histological study of this pathologic tissue revealed an “angiofibroblastic tendinosis” in which micro-tears in the tendon were replaced with disorganized immature collagen, fibroblasts, and vascular tissue [22–24]. As confirmed by subsequent authors, a lack of inflammatory cells was observed; however, this description is also consistent with that of normal tendons that were injected with corticosteroids, and no studies have confirmed the histologic appearance of a diseased tendon without corticosteroid exposure [25]. Arthroscopically, the tendon appears to have varying degrees of fraying, tearing, and avulsion with increasing severity of disease [9].

26.6 Treatment Options

Up to 95 % of patients presenting with tennis elbow will improve without surgery [15]. Although the optimal conservative therapy for lateral epicondylitis is unclear, it is reasonable to approach the patient with a combination of brief rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs followed by physical therapy, bracing, and injections if needed.

26.6.1 Nonoperative Treatment

26.6.1.1 Physical Therapy, Bracing, and Activity Modification

Successful results have been described with physical therapy regimens utilizing a combination of stretches, targeted massage, strengthening, and hot-cold modalities [15, 26–28]. Eccentric muscle training has demonstrated excellent results with subjective improvement in both pain and strength [29]; resistance physiotherapy is the authors’ preferred modality. Newer treatments such as extracorporeal shock wave therapy and topical glyceryl trinitrate patches do not have long-term data to support their routine use at this time [28, 30].

Physiotherapy may also include sport-specific technique and equipment modifications. When compared with professionals, amateur players experience tennis elbow symptoms more frequently which suggests that poor technique is contributory [2, 13, 14, 31]. A tennis coach can teach the player to concentrate the core muscles into the forehand swing by striking the ball while it is still in front of the player. Additionally, in a one-handed backstroke, the coach should focus on making sure the player extends the wrist during ball contact; striking the ball while the wrist falls in flexion creates a greater eccentric load on the wrist extensors. Alternatively, a 2-handed backstroke can also help unload the tension across the dominant wrist. Equipment should also be inspected. Lighter rackets made of low-vibration materials (graphite or epoxies) and rackets that are less tightly strung and/or have more strings per unit area can also reduce the work of the wrist extensors during active play [32]. A proper grip size is also recommended; a good estimate of the racket handle circumference is to measure the distance from the players proximal wrist crease to the tip of the ring finger. Last, playing on “slower” surfaces, such as a clay court, may also reduce the forces experienced across the wrist.

Orthoses can be an adjunctive therapy for tennis elbow but are not usually prescribed as a monotherapy. Counterforce straps are wrapped tightly around the upper forearm in an attempt to move the mechanical origin of the wrist extensors more distal; thus the player, in theory, can still move the wrist while resting the proximal portion of the muscles [28, 33]. Cock-up wrist splints are another option, which restrict wrist extension. Currently, no orthosis has been proven superior [34].

26.6.1.2 NSAIDs and Injections

A recent Cochrane review examined 13 trials that reported on the efficacy topical and oral NSAIDs for symptom relief in lateral epicondylitis and could not recommend for or against their use. Symptom alleviation in some patients was offset by the side effects of stomach pain and diarrhea with oral tablets and skin rash with topical applications [35].

Steroid injections alleviate elbow pain and assist with early return to athletic or work activity, although no long-term benefit has been established [28, 36]. Comparative studies have not found a superior steroid preparation, although universal risks for all steroid injections are skin depigmentation, fat atrophy, tendon rupture, and transient hyperglycemia in diabetics [37, 38].

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and whole blood injections are an alternative to steroids and have been used with more frequency in recent years. A prospective study by Mishra et al. with 230 participants demonstrated clinical improvements at 24 months compared with controls [39]. Gosens et al. also showed greater clinical improvement with PRP compared to corticosteroids at 2 years [40]. Thanasas et al. was unable to demonstrate better outcomes with PRP compared to whole blood injections at 6 months [41]. Currently, the optimal timing, concentration, and number of doses of these biologic injectables are not known, and the cost can be prohibitive for some patients.

26.6.2 Operative Treatment

Surgery is reserved for patients who do not improve with 6–12 months of nonoperative therapy. Excellent results have been documented with open, percutaneous, and arthroscopic approaches to the lateral elbow [42]. Overall, long-term pain relief following surgery ranges from 19 to 100 % [43, 50]. The average failure rate is 5.8 % [3], and return to sport following surgery averages 66 days [42]. Arthroscopic release has reported success rates of 93–100 % [50] with an average return to sport at 35 days [42]. No single technique has been proven superior for either relief of symptoms or return to play [46].

The “mini”-open release is the most common approach, where the ECRB origin is released through a 3 cm incision over the lateral epicondyle. The interval between the extensor carpi radialis longus and the extensor digitorum communis is incised and raised subperiosteally. The ECRB origin should then be exposed and the degenerated tissue should be examined and graded. Some surgeons prefer to resect the tendon while others may detach it, debride the undersurface, and reattach it with suture anchors. In both cases, the lateral epicondyle is usually decorticated prior to repair/closure in order to stimulate tissue healing. Strict protection of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament is critical in maintaining elbow stability.

The percutaneous tenotomy is performed through a 1 cm incision in the office or in the operating room. The procedure does not include removal of pathologic tissue and can therefore predispose the patient to recurrence of symptoms. Advantages include convenience and short recovery times [43, 44].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree