CHAPTER 5 Arthroscopic Knot Tying

The last 2 decades have been a period of dynamic and exciting growth in the field of reconstructive arthroscopy. The drive of patient demand, availability of improved instrumentation and implants, and increasing acceptance of arthroscopic reconstructive techniques by the orthopedic community have all fueled development of increasingly complex arthroscopic reconstructive surgical procedures. The ability to approximate tissue with confidence is a cornerstone of complex arthroscopic procedures and integral to this advancement has been the evolution of arthroscopic knot tying. Unfortunately, development of arthroscopic knot tying skills has proven a stumbling block to many arthroscopists because arthroscopic knot tying is not as intuitive as open knot tying. Recognizing this frustration, many device and implant manufacturers and a number of innovative orthopedic surgeons have devised ways whereby an orthopedist can accomplish some of these reconstructive techniques without the need for tying knots arthroscopically.1–8 These techniques are, by their nature, dependent on a particular piece of equipment or implant, which subject to the same risk of failure at the time of surgery as any other implant or device. Thus, although these techniques may allow a surgeon to bypass knot tying in some cases, the prudent orthopedist would not undertake a complex arthroscopic reconstructive procedure that relies on tissue fixation without the ability to accomplish basic arthroscopic knot tying as a backup plan. Perhaps more importantly, the ability to tie knots arthroscopically also gives the reconstructive arthroscopist freedom to tailor specific reconstructions to the needs of the patient without being constrained by those options allowed by knotless devices.

LEARNING TO TIE KNOTS ARTHROSCOPICALLY

The quickest and most certain way to learn arthroscopic knot tying is to attend hands-on instructional courses such as the Master’s Series courses presented by the Arthroscopy Association of North America (www.aana.org). These 3-day courses, offered throughout the year, provide sustained knot tying instruction in both didactic and laboratory formats. In the laboratory setting, experienced surgeons are available to assist and troubleshoot the student’s knot tying as dexterity is achieved.

DEFINITIONS

INSTRUMENTATION FOR ARTHROSCOPIC KNOT TYING

Sutures

The decision between dissolving (e.g., PDS II, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) and permanent (e.g., Ethibond Excel, Ethicon) suture depends both on surgeon preference and situation-specific factors such as the nature of the reconstruction and the particular tissue being approximated in the process of that reconstruction. Historically, monofilament suture has been easier to pass with available arthroscopic suturing instruments but in general is more difficult to tie securely,10–12 presumably because of differences in surface characteristics of the two types of suture.

A new class of high-strength braided suture incorporating ultra–high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) has recently become available. These sutures, including FiberWire (Arthrex, Naples, Fla), Orthocord (DePuy-Mitek, Raynham, Mass), Hi-Fi (ConMed Linvatec, Largo, Fla), Ultrabraid (Smith & Nephew, Andover, Mass), Force Fiber (Stryker Endoscopy, San Jose, Calif), MagnumWire (ArthroCare, Sunnyvale, Calif) and MaxBraid PE (Biomet, Warsaw, Ind), have been shown to have improved mechanical properties compared with traditional suture materials, but have also been shown to have different knot security qualities.13–17 These differences in knot security qualities, presumably caused by differences in surface properties, mandate the need for additional half-hitches to lock these knots. One recent study has demonstrated that a total of four locking half-hitches backing a sliding arthroscopic knot is not enough to prevent knot slippage reliably with these high-strength sutures.17 The authors did not give a recommendation regarding the appropriate number of locking half-hitches needed. Other investigators have suggested that the addition of two locking half-hitches beyond the number that would be used to secure more traditional suture materials is sufficient for reliable knot security.14

Some of the newer high-strength sutures provide greater bulk than the same knots tied with traditional sutures.13 Selecting a knot with a lower profile may be very important when using newer high-strength sutures. The surgeon should also be aware that damage to gloves and even finger skin tears can be sustained when tying vigorously with these high-strength suture materials.18 Moderation of vigor when tying any knot is sensible, especially when tensioning the tissue loop to avoid tissue strangulation.

Knot Pushers

Several different knot pusher designs are available to the arthroscopic surgeon—single-hole, double-hole slotted, mechanical spreading, and dual-lumen single-hole. Single-hole knot pushers are the most commonly used type because they can easily push a knot down by placement on the post limb, or pull a loop down by placement on the wrapping limb. Double-hole knot pushers can be used for these tasks as well, but their added size and bulk confer no advantage and can complicate passage of individual knot loops. Double-hole knot pushers find their main use in correcting twists of the suture limbs prior to knot tying. Both suture limbs are threaded through the knot pusher and the pusher is advanced to the target tissue intra-articularly. Any twist of the sutures is immediately evident and can be corrected with a simple clockwise or counterclockwise turn of the knot pusher as both limbs are captive in the tip of the knot pusher. Slotted knot pushers function similarly to single-hole knot pushers, but allow the knot pusher to be applied and removed from the suture strand without having to withdraw the knot pusher from the joint. This capability can be a liability, however, if the knot pusher is inadvertently separated from the intended suture limb during the process of tying. The incomplete loop of the knot pusher tip also opens the door for soft tissue entanglement. The dual-lumen single-hole knot pusher is designed to hold tension in that portion of the knot already passed while additional throws are tied and advanced. Investigation has shown this knot pusher design to be very effective in achieving loop security during arthroscopic knot tying.19 This knot pusher does however represent a per-use cost (it is disposable), requires use of longer sutures (36 instead of 27 inches), and may require a greater degree of technical proficiency. The dual-lumen single-hole knot pusher is most useful when the surgeon has to tie a nonsliding knot. These nonsliding knots do not have a sliding component to hold temporary tension in the initial (tissue) loop while additional securing throws are being passed. By virtue of its design, the dual-lumen single-hole knot pusher provides this tension, and therefore good loop security, even with simple half-hitch–based nonsliding knots.

TIPS AND TRICKS FOR INSTRUMENTATION

Suture Anchors

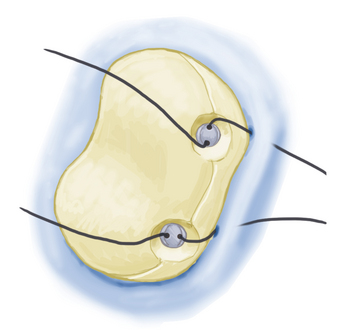

Overpenetration of suture anchors into bone should be avoided because this recesses the suture eyelet relative to the cortical surface, potentially leading to abrasion of the suture on the edge of the suture anchor tunnel as the suture exits the tunnel. This can lead to suture failure. For anchors with fixed (nonsuture) eyelets, the eyelet should be aligned when sinking the anchor so that the suture path is aligned with knot tying (Fig. 5-1).