The ICF in the Historical Perspective

Clinicians have relied on classifications for the diagnosis of health conditions for over 100 years (

10,

11). The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) was first published as a classification of causes of death in 1898 (

12). In the meantime, the ICD is undergoing its 11th revision. The ICD was initially used for actuarial reasons to document death. It was later adopted for epidemiology and by public health to monitor health and interventions. Lately, it was used for clinical purposes, mainly driven by the need to classify diagnoses in the context of reimbursement systems including diagnostic-related groups.

By contrast, the first classification of disability, the International Classification of Impairment, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH) (

13) was published and released in 1980 for trial purposes only. The ICIDH and other models like the Institute of Medicine model (

14,

15), Nagi’s model (

16,

17), and the Quebec model (

18) have influenced the definitions of rehabilitation (

9), the development of rehabilitation practice and research (

9), and legislation and policy-making (

7,

15). The ICIDH model of disablement represented a real breakthrough in that disability was disentangled from disease by removing the disability section from ICD-8 and creating a separate classification.

Particularly in Europe, there was considerable interest in the application of the ICIDH as a unifying framework for classifying the consequences of disease during the last 20 years of the 20th century. For example, the Council of Europe launched its

Recommendation No. R (

92)

6 on “a coherent policy for people with disabilities” based on the ICIDH (

19). Other publications by the Council of Europe, for example, about the use and usefulness of the ICIDH for health professions (

20) document this interest.

However, the ICIDH, which was never approved by the World Health Assembly as an official WHO classification, did not find worldwide acceptance (

1,

15). It was criticized by the disability community over time for the use of negative terminology, such as handicap, and for not explicitly recognizing the role of the environment in its model. In the reprint of the ICIDH in 1993, WHO thus expressed its intention to embark in the development of a successor classification.

The ICF in the WHO and the UN Perspective

The endorsement of the ICF by the 54th World Health Assembly in May 2001 mirrors an important shift in the understanding of health and disability by the WHO. The ICF acknowledges that every human being can experience a decrement in health and thereby experience some disability. With the ICF, WHO responds to the need for a unified, international, and standardized language for describing and classifying health

and health-related domains. The ICF is WHO’s framework for health and disability. It is the conceptual basis for the definition, measurement, and policy formulations for health and disability. The ICF thus complements the ICD that is used to classify deaths and diseases (

11). To complement mortality or diagnostic data on morbidity and diseases is important since they alone do not adequately capture health outcomes of individuals and populations (e.g., diagnosis alone does not explain what patients can do, what their prognosis is, what they need, and at what treatment costs) (

21,

22).

As an international standard ICF contributes to various WHO’s efforts related to the measurement of health and disability. For example, the ICF served as a framework for WHO’s World Health Survey conducted in 70 countries (

23,

24). The WHA resolution 58.23 on “

Disability, including prevention, management and rehabilitation” approved in May 2005 by the 58th World Health Assembly recalls the ICF framework (

8). For the upcoming WHO World Report on Disability and Rehabilitation, the ICF provides the basis for the conceptualization of disability and reference framework for the disability statistics presented in the report. The International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM) which is the International Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (PRM) organization in official relation with WHO, is represented on the advisory board of the report and is supporting the DAR team in this development.

While the ICF has been developed by WHO, the specialized agency responsible for health within the United Nations (UN) system, the ICF has been accepted as one of the UN social classifications (

4). Therefore, the ICF has influenced the characterization of disability in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (

25) approved on 13 December 2006 at the UN Headquarters in New York. While the convention does not establish new human rights, it does define the obligations on states to promote, protect, and ensure the rights of persons with disabilities. Most importantly, it sets out the many steps that states must take to create an enabling environment so that persons with disabilities can enjoy inclusion and equal participation in society. However, the ICF provides a more comprehensive approach defining disability than it is used in the UN Convention. Hence, there is the need for a common agreement on the meaning of disability (

26).

Development of the ICF

The ICF was developed by the WHO in a worldwide collaborative process involving the active participation of some 65 countries and a network of WHO Collaboration Centers for the Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC). After three preliminary drafts and extensive international field testing, including linguistic and cultural applicability research, the successor classification which was first tentatively named ICIDH-2, the ICF was finalized in 2000 (

4). So far, the ICF has been translated into 37 languages.

The ICF not only was derived from Western concepts but has worldwide cultural applicability. The ICF follows the principle of a universal as opposed to a minority model. Accordingly, it covers the entire lifespan. It is integrative and not merely medical or social. Similarly, it addresses human functioning and not merely disability. It is multidimensional and interactive, and rejects the linear linkage between health condition and functioning. It is also etiologically neutral which means functioning is understood descriptively and not caused by diagnosis. It adopts the parity approach which does not recognize an inherent distinction or asymmetry between mental and physical functioning.

These principles address many of the criticisms of previous conceptual frameworks and integrate concepts established during the development of the Nagi model (

16,

17) and the Institute of Medicine model of 1991 (

14,

15). Most importantly, the inclusion of environmental and personal factors, together with the health condition, reflect the integration of the two main conceptual paradigms that had been used previously to understand and explain functioning and disability, that is, the medical model and the social model.

The medical model views disability as a problem of the person caused directly by the disease, trauma, or other health conditions and calls for individual medical care provided by health professionals. The treatment and management of disability aim at cure and target aspects intrinsic to the person, that is, the body and its capacities, in order to achieve individual adjustment and behavior change (

27,

28).

By contrast, the social model views disability as the result of social, cultural, and environmental barriers that permeate society. Thus, the management of disability requires social action, since it is the collective responsibility of society at large to make the environmental modifications necessary for the full participation of people with disabilities in all areas of social life (

29,

30,

31,

32). The ICF and its framework achieve a synthesis, thereby providing a coherent view of different perspectives of health (

1).

ICF Update and Future Developments

The ICF published in 2001 will—similar to the ICD—undergo updates and ultimately a revision process. The WHO coordinates the update process, in collaboration with the Network of the Collaboration Centers for the Family of International Classifications (WHO FIC CC Network). Recognizing the importance of personal factors, which are included in the ICF conceptual model, the WHO is also exploring the possibility of developing a taxonomy of personal factors.

To meet the requirements of health and disability information systems in the 21st century, the digitalization of analogue information standards as used with the ICF is essential. This is why the work on an ICF Ontology (defining classification entities with their attributes and value sets) is regarded as a priority for future ICF development.

The Structure of the ICF

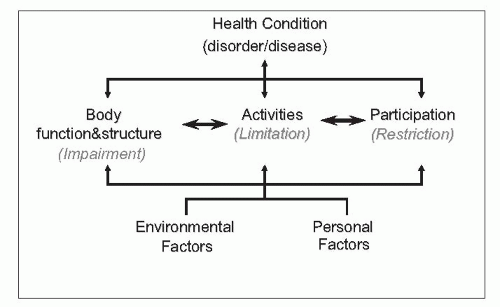

As shown in

Figure 11-1, the ICF is organized into two parts. Part 1 classifies functioning and disability formulated in two

components: (a) body functions and structures and (b) activities and participation. Part 2 comprises the contextual factors which include the following two components: (a) Environmental factors and (b) Personal factors (currently not classified).

Definitions of some of the key terms used in ICF are given below.

Health condition is an umbrella term for disease (acute or chronic), disorder, injury, or trauma. A health condition may also include other circumstances such as pregnancy, ageing, stress, congenital anomaly, or genetic predisposition. Health conditions are coded using ICD-10.

Functioning is an umbrella term for body functions, body structures, activities, and participation. It denotes the positive aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that of an individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors).

Disability is an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. It denotes the negative aspects of the ICF that provides a detailed classification with definitions: body functions are the physiological functions of body systems (including psychological functions); body structures are anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs, and their components; activity is the execution of a task or action by an individual; participation is involvement in a life situation; environmental factors make up the physical, social, and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives.

The component of body functions and structures refers to physiological functions and anatomic parts of the body system, respectively; loss or deviations from normal body functions and structures are referred to as impairments. The second component of activities and participation refers to a single list of life domains (from basic learning or walking to composite areas like interpersonal relationships or employment). The component can be used to denote activities or participation or both. “Activity limitations” are thus difficulties the individual may have in executing activities (

7). “Participation restrictions” are thus problems the individual may experience with such involvement (

7). The components of body functions and structures and activity and participation are related to and may interact with the health condition (e.g., disorder or disease) and contextual factors.

Contextual factors include the components of environmental factors and personal factors. Since in the current ICF, an individual’s functioning and disability occurs in a context, ICF also includes a classification of environmental factors. The components of body functions and structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors are classified based on ICF categories. It is conceivable that a list of personal factors will be developed over the next years. The ICF contains a total of 1,495 meaningful and discrete or mutually exclusive categories. Taken together, the ICF categories are cumulative exhaustive and hence cover the whole spectrum of the human functioning. The categories are organized within a hierarchically nested structure with up to four different levels as shown in

Figure 11-2. The ICF categories are denoted by unique alphanumeric codes with which it is possible to classify functioning and disability, both on the individual and population level.

An example of the hierarchically nested structure is as follows: “b1 Mental functions” (first/chapter level); “b130 Energy and drive functions” (second level); and “b1301 Motivation” (third level). Based on the hierarchically nested structure of the ICF categories, a higher-level category shares the attributes of the lower-level categories to which it belongs. In our example, the use of a higher-level category (b1301 Motivation) automatically implies that the lower-level category is applicable (b130 Energy and drive functions).

Because the ICF categories are always accompanied by a short definition and inclusions and exclusions, the information on aspects of functioning can be reported unambiguously. Examples of ICF categories, with their definitions, inclusions, and exclusions are shown in

Table 11-1.