Fig. 37.1

Surface markings for deltopectoral approach. Ac, Acromion; Clav, clavicle; Co, Coracoid process

The presence of the vein is usually marked by a longitudinal streak of fat running in the groove. However, this streak of fat may be absent or difficult to define in a particularly slender patient; in the presence of a deep, vestigial or absent vein; or revision surgery. In these situations the interval is easier to define proximally, closer to the clavicle, as the orientation of deltoid and pectoral muscle fibres converge distally. Palpating the underlying coracoid process may also assist in locating the interval.

Tip

Identification of the cephalic vein can be difficult, but it can usually be located in the fat just superficial to the coracoid process in the proximal extent of the deltopectoral interval.

It is easier to dissect between the cephalic vein and the pectoralis major muscle as most of the tributaries of the vein run between the lateral aspect of the vein and the deltoid muscle. However, one shortcoming of taking the vein laterally is that proximal extension of the approach may put the cephalic vein at risk where it crosses from lateral to medial in the proximal part of the incision. For that reason if it is anticipated that more extensile exposure is required then it may be preferable to spend a little more time ligating the tributaries on the lateral aspect of the vein and separating the vein from the deltoid and taking it with the pectoralis major.

37.3.1.3 Deep Dissection

Having defined and developed the deltopectoral interval, the principle anatomy of the anterior aspect of the shoulder as it relates to the deltopectoral approach may be defined by two critical bony landmarks. One of these bony landmarks is fixed and the other is mobile and both are of equal importance in developing appropriate surgical exposures in this region.

The fixed bony landmark is the coracoid process. It is encountered in the proximal aspect of the deltopectoral interval as soon as the two muscles are separated. The coracoid process has four key attachments with one from each direction. From the medial aspect is the tendon of pectoralis minor (Fig. 37.2). Superiorly and more toward the root of the coracoid process are the conoid and trapezoid coracoclavicular ligaments (Fig. 37.3). Laterally is the coracoacromial ligament (Fig. 37.4) and inferiorly is the conjoint tendon of the short head of biceps and the coracobrachialis muscle (Fig. 37.2).

Fig. 37.2

Medial and inferior relations of coracoid process: Anterior view, pectoralis major removed, anterior deltoid retracted laterally. a musculocutaneous nerve; b pectoralis minor; c tip of coracoid process; d coracobrachialis; e short head of biceps; f clavicle; g lateral pectoral nerve

Fig. 37.3

Superior relations to coracoid process: Coracoclavicular ligaments superior view, AC joint capsule divided and clavicle rotated anteriorly. a acromion; b coracoacromial ligament; c lateral clavicle; d trapezoid ligament; e conoid ligament; f transverse scapular ligament across scapular notch

Fig. 37.4

Coracoacromial ligament: Direct lateral view, deltoid removed, clavicle removed. a acromion; b coracoacromial ligament; c coracoid process; d conjoint tendon; e coracohumeral ligament; f supraspinatus

Once the coracoid process has been identified, the clavipectoral fascia is encountered lateral to the conjoint tendon and inferior to the coracoacromial ligament (Figs. 37.5 and 37.6). Incision of this fascia allows access to the subdeltoid space.

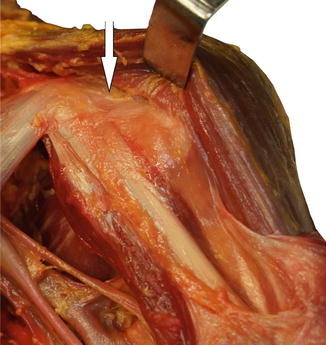

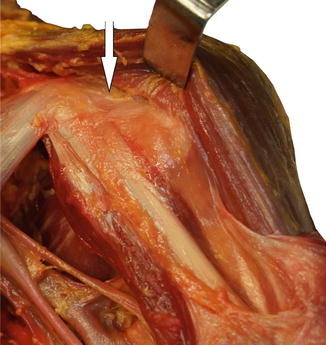

Fig. 37.5

Clavipectoral fascia indicated by arrow

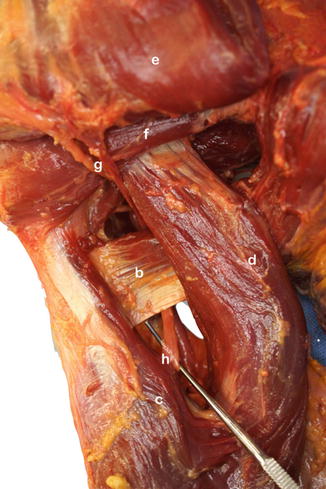

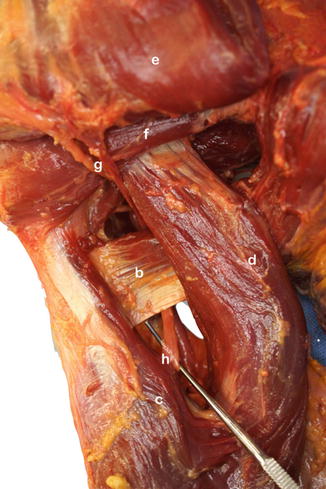

Fig. 37.6

Rotator cuff and coracoacromial ligament: Anterior view, deltoid detached distally and reflected laterally. a undersurface of reflected deltoid; b coracoacromial ligament; c coracoid process; d coracoclavicular ligament (conoid); e subacromial space; f supraspinatus; g subscapularis; h coracohumeral ligament; i conjoint tendon; j undersurface lateral clavicle

Danger

The axillary nerve is held to the undersurface of the deltoid by fascia, so is at risk if the deltoid is split.

Tip

The safe subdeltoid plane is found by identifying the subacromial space immediately deep to the coracoacromial ligament and sweeping laterally and distally under the deltoid.

The axillary nerve arises from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus and exits the quadrilateral space posteriorly, primarily to supply the deltoid muscle. The posterior boundaries of the quadrilateral space vary in regard to the anterior boundaries, that is, the superior margin is defined by teres minor instead of subscapularis (Fig. 37.7).

Fig. 37.7

Posterior view of quadrilateral and triangular spaces, teres major and latissimus dorsi: Posterior view, deltoid retracted superiorly. b teres major; c lateral head of triceps; d divided long head of triceps; e deltoid reflected superior; f teres minor; g axillary nerve; h radial nerve

Once the axillary nerve enters the posterior aspect of the shoulder it wraps around the proximal humerus, closely applied to the deep surface of the deltoid muscle. It travels with the posterior circumflex humeral vessels.

There is a constant vessel branching from the circumflex humeral vessels deep to the anterior third of deltoid (Fig. 37.8). The significance of this vessel is twofold. Most surgical procedures via a deltopectoral approach require definition and mobilisation of the subdeltoid space. This vessel is a frequent cause of troublesome bleeding which may be avoided if it is identified and controlled, rather than incidentally disrupted during subdeltoid mobilisation. However, care should be taken not to damage the axillary nerve when controlling this vessel, particularly when using electrocautery. In addition, this vessel can be used as a marker of the level of the axillary nerve on the deep surface of deltoid. The distance from the lateral margin of the acromion to the axillary nerve is variable, but may be as little as 4 cm.

Fig. 37.8

Axillary nerve and deltoid: Lateral view, deltoid detached distally and hinged posteriorly. a deltoid; b axillary nerve and circumflex humeral vessels; c meta-diaphyseal junction of humerus; d humeral branch from posterior circumflex vessels; e long head of biceps; f conjoint tendon; g coracoacromial ligament

The mobile bony landmark for the deltopectoral approach, which further facilitates identification of critical structures, is the bicipital groove. The location of the groove depends on the rotation of the humerus. However, in general, it is directly anterior when the humerus is in neutral rotation (as judged by the position of the forearm with the elbow flexed). The bicipital groove and related structures are in a deeper plane than the coracoid process and their identification requires division of the clavipectoral fascia as discussed earlier (Fig. 37.5), particularly lateral to the coracoid and inferior to the coracoacromial ligament.

The groove is occupied by the long head of biceps tendon. The biceps tendon may be traced superiorly to identify the rotator interval between the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons and is one of the critical intervals for developing exposure to the glenohumeral joint. The medial aspect of the bicipital groove is formed by the lesser tuberosity to which is attached the subscapularis tendon superiorly and subscapularis muscular attachment to the humerus inferiorly (Fig. 37.9a). As the biceps tendon is traced more distally to the shallower portion of the bicipital groove, the tendon is covered by the pectoralis major tendon, which inserts on the lateral lip of the bicipital groove. The pectoralis major tendon insertion is quite complex with crossing over of the fibres such that the costal fibres tend to insert more superiorly and the sternal and clavicular fibres tend to insert more inferiorly. At this level within the floor of the bicipital groove is the insertion of the flat ribbon-like latissimus dorsi tendon, and closely related to the latissimus dorsi insertion and just inferior to the subscapularis muscle insertion is the insertion of the teres major tendon into the medial lip of the bicipital groove. Although closely related and sometimes harvested together as a dual tendon transfer, these tendons are almost completely separate (Fig. 37.9b). There is also a well-defined bursa between the posterior aspect of the latissimus tendon and the medial aspect of the humeral shaft.

Fig. 37.9

(a) Bicipital groove, latissius and teres major: Anterior view, coracobrachialis and short head of biceps retracted laterally. a latissimus dorsi tendon; b bicipital groove; c teres major tendon; d divided stump of insertion of pectoralis major; e subscapularis; f coracobrachialis; g long head of biceps displaced laterally out of groove. (b) Latissimus and teres major tendons: Anterior view, coracobrachialis and short head of biceps retracted laterally, latissimus dorsi reflected laterally. a undersurface of latissimus dorsi tendon; b bursa on humeral shaft deep to latissimus tendon; c teres major tendon; d tenuous connection between latissimus and teres major tendons

If there is a significant internal rotation contracture, such as in osteoarthritis, the pectoralis major insertion may be partially or completely released. This may assist in the disclocation of the joint during arthroplasty. If a complete release is required, then consideration may be given to placing a tagging suture in the pectoralis tendon in order to allow subsequent repair.

37.3.1.4 Clavicular Osteotomy and Deltoid Release

The deltoid origin can run a considerable distance along the clavicle, which may make access to the joint more difficult. The temptation to improve access by aggressive retraction should be avoided, as the retractors can bruise or cut into the anterior deltoid. If access is limited then release of the anterior deltoid can significantly improve access to the joint. This release also allows improved access to the lateral aspect of the proximal humerus, which is of particular value in fracture management, where ideal plate positioning is often compromised by poor access. There are two ways of releasing the anterior deltoid:

1.

Clavicular osteotomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree