25 Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a seronegative inflammatory autoimmune disease of unknown etiology and is one of the spondylarthritides commonly associated with HLA-B27.1–6 This disease manifests around the third or fourth decade and is more common among Western societies. The worldwide prevalence has been determined to be 0.9%.2,5 The disease affects an average of 350,000 persons in the United States and around 600,000 in Europe, primarily white males.3 Diagnosis of AS is often delayed and can take an average of 3–11 years from the onset of symptoms3,4 The end result of the disease is early retirement and severe functional impairment in ~ 30% of the affected population.7 AS is also known as Bekhterev disease, as it was originally described and published by the Russian neurophysiologist Vladmir Bekhterev (or Bechterew). Significant contributions were made by Pierre Marie and Adolph Strumpell.1,8 AS has been classified and described based on the Rome and New York diagnostic criteria,9–11 established solely on clinical and radiologic manifestations. These criteria, originally established in 1961 and 1966, respectively, have been modified over subsequent years to improve sensitivity and specificity (Table 25.1). The precise etiology of AS is unknown. A strong genetic linkage has been confirmed and established with the major histocompatibility human leukocyte antigen (HLA) HLA-B27, but unavailability of routine biopsy makes it highly unlikely for the disease to be diagnosed at an earlier stage. Carriers of HLA-B27 have a 16% greater risk of acquiring the disease than noncarriers, and the probability of having AS is increased by 10 times after testing positive for HLA-B27.6,12 Besides the HLA-B27 genetic linkage, it has been hypothesized that involvement of the IL-23 signaling pathway could be a determinant in the development of AS. Inflammatory mediators involved in the disease process usually are CD4 and CD8 helper T lymphocytes, along with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β.8,12 Table 25.1 The Modified New York Classification Criteria for Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing Spondylitis

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Etiology and Pathophysiology

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Clinical Criteria | – Low back pain for a minimum 3 months, relieved by exercise but not rest |

– Limited sagittal and frontal plane lumbar spinal motion | |

– Decreased chest expansion contrary to age and sex | |

Radiological Criteria | – Bilateral sacroilitis, grade 2–4 |

– Unilateral sacroilitis, grade 3–4 Source: van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–368. |

Pathogenesis of the disease is immune mediated and begins where articular cartilage, ligaments, and other structures attach to the bone (enthesis). Involvement of the sacroiliac joint is considered a hallmark for the disease and a requirement for diagnosis. The axial skeleton is involved to a variable extent. Sacroiliitis along with synovitis, mucoid marrow, subchondral granulation tissue, enthesitis, and chondroid differentiation are usually found and accompanied by fibrocartilage regeneration and ossification of the eroded joint margins. This ultimately results in complete joint fusion.5,9,10,13

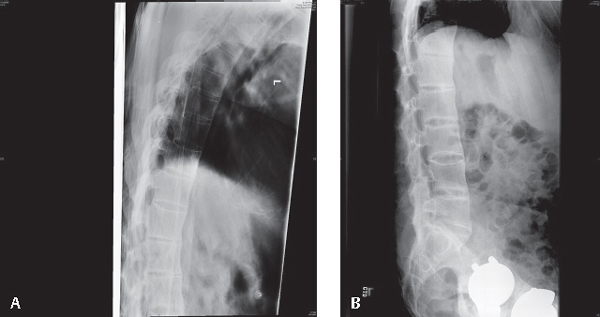

In the spine, inflammatory granulation tissue at the junction of the annulus fibrosus and vertebral bone leads to the formation of a syndesmophyte, which gradually progresses, along with diffuse osteoporosis and squaring of vertebrae, and finally results in bony ankylosis (Fig. 25.1A,B).8,9,14 This ultimately results in the characteristic “bambooing” of the spine seen on radiographs.

The spinal column becomes very rigid and brittle and highly susceptible to injury. Any fracture should be considered to involve both spinal columns and to be highly unstable.15

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Patients with AS usually present with one of the following complaints:

• Dull, aching, deep, and insidious-onset pain in the neck or lower lumbar region as well as gluteal region

• Spinal deformity: inability to look straight forward, chin-to-chest deformity, tipping forward

• Spinal fracture

• Spinal stenosis, leg weakness, neurologic claudication

Fig. 25.1 (A) Thoracic spine ankylosis. (B) Lumbar spine ankylosis and loss of lumbar lordosis.

Seventy percent of patients with AS report daily pain and stiffness, 20% of patients display signs and symptoms of emotional problems, 47% present with physical disability, and 60% of patients present with fatigue.

Articular sites of AS usually involve the proximal, large joints (sacroiliac, hip, and shoulder joints), but peripheral joints may be involved as well. Bony tenderness at various locations (costovertebral junction, spinous process, iliac crests, ischial tuberosities, tibial tubercles, heels, and greater trochanter) may accompany lower back pain or stiffness or can be a primary complaint. Shoulder and hip involvement occurs in ~ 50% of the patients who also have involvement of more distal joints. Spinal involvement usually involves flattening of the normal lumbar lordosis and an increasingly smooth thoracic kyphosis, with the head and neck thrust forward. This increased kyphosis may lead to a “chin-on-chest” deformity and may make it difficult or impossible for the patient to look straight ahead (Fig. 25.1A,B).9,11,16–18 The level of deformity must be assessed clinically by either chin-brow angle, occiput-to-wall distance, or hip flexion contracture. Other measurements of spinal mobility, especially fingertip-to-floor distance, lateral spine flexion, modified Schober’s index, and tragus-to-wall distance, may be performed to evaluate disease status.9

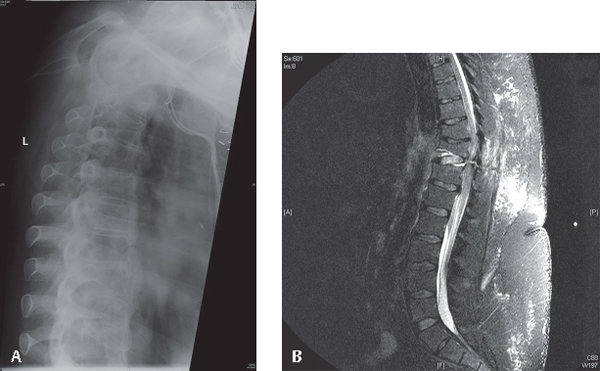

One of the most serious presentations of patients with AS is spinal fractures. Fractures commonly occur with a distraction-extension pattern and may be the result of relatively minor injuries. Even though they appear benign (Fig. 25.2A,B), these fractures can be highly unstable, with high rates of catastrophic neurologic injuries. Epidural hematomas are often present and can lead to further neural compression. Wedging of the thoracic vertebrae is common and leads to accentuated kyphosis. Rarely, traumatic disk degeneration and secondary dislocation has been observed with highly ossified AS spine fractures.

Fig. 25.2 (A) Thoracic radiographs showing what can be perceived as minor stable fracture. (B) MRI, T2-weighted images showing a highly unstable extension injury to the thoracic spine seen in (A).

Imaging

Imaging

The earliest radiographic changes seen in AS are blurring of the cortical margins of the subchondral bone, erosions and sclerosis. Imaging the lumbar spine reveals straightening due to loss of lordosis and reactive sclerosis. Marginal syndesmophytes are visible on plain radiographs. Spinal osteoporosis along with spondylodiskitis, ligament ossification, and involvement of the facet joints may be evident on plain radiographs or computed tomography (CT). CT scans with sagittal reconstruction have been recommended to assess the level of the lesion as well as any concomitant spinal cord lesions or epidural hematoma. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with fat saturation is now being used to detect the early intraarticular inflammation, cartilage changes, and underlying bone marrow edema in sacroiliitis.9,18

For patients with AS who sustain traumatic injuries, radiographs should be critically analyzed. It should be assumed that every fracture of the spinal column is a bicolumnar injury, and MRI and/or CT scanning should be performed (Fig. 25.2A,B)19,20

Treatment

Treatment

The treatment modalities should be tailored to address the presenting complaints as just illustrated.

Nonsurgical Management

This is the primary treatment of patients with chronic neck and back pain with or without mild or moderate spinal deformity. It is primarily based on optimal utilization of nonpharmacologic as well as pharmacologic treatment modalities. Nonpharmacologic modalities focus on patient education and regular exercise. Genetic counseling and patient support groups are useful in further educating the patient on the disease.21 Regular exercises through physical therapy should focus on maintaining posture and improving range of motion to avoid the long-term outcome of flexion deformity of the spine.

Pharmacological treatment modalities, especially nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), have long been considered the cornerstone of intervention for AS. They have been shown to reduce pain and stiffness rapidly within 48–72 hours. Phenylbutazone and indomethacin were among the first NSAIDs to be used; however, recently emphasis has shifted to cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors. With the use of celecoxib and etoricoxib, 70–80% patients have reported a better outcome. However, continuous therapy with NSAIDs has not been shown to decrease the development of spinal deformity. Oral steroids are not used for long term because of potential adverse effects. Sulfasalazine has been reported to be effective in some patients with peripheral involvement along with coexisting inflammatory bowel disease.20,22

Promising results have been shown with anti-TNF medications (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept) in outcomes of the disease either clinically, radiologically, or in terms of laboratory measures. Infliximab is given as 3–5 mg/kg body weight, repeated 2 weeks after, followed by 6 weeks, and then at 8-week intervals.20,22,23 Significant improvements have been reported in both objective and subjective indicators of the disease.9 Extraskeletal manifestations also need to be treated appropriately. Osteoporosis is a frequent manifestation of AS, and use of bisphosphonates has been reported in the past for managing osteoporosis. Some recent studies have shown the effectiveness of anti-TNF agents in increasing bone mineral density after 6 months of treatment.

Surgical Management

Surgical treatment is usually reserved for the treatment of significant spinal stenosis, spinal deformities, and fractures.

Spinal Deformities

Management of AS-related deformities is associated with a significantly high rate of complications due to the location of the deformities, the diffuse nature of ankylosis, and the patient’s overall health status.24 Multiple and incremental corrective osteotomies based on the posterior elements, such as wide facetectomy, Smith-Peterson, or Ponte osteotomies, are not applicable for patients with AS, as they rely on an open disk space for anterior column mobility. Any osteotomy used for AS has to involve both the anterior and posterior spinal columns.

When the cervicothoracic junction is affected, patients with abnormal chin-brow angle or chin-on-chest deformity can have significant impairment in both looking straight25 and swallowing. This severe kyphosis is best addressed at the C7 level, since the vertebral arteries enter the spine rostral to it (90% of the time) and there are no rib attachments. Corrective osteotomy via either a posterior approach or a combined posterior-anterior approach is the definitive treatment.4,26 The possibility of neurologic complications with the anterior approach is relatively high, compared with the posterior approach.4,26–28 Opening-wedge osteotomy has been associated with development of permanent neurologic complications.28,29 33% of the instrumentation failure cases have been reported.

Osteotomies at the thoracic or lumbar spine are also technically challenging, but complications have been noted to be relatively rare with posterior-based closing-wedge osteotomies.30–33

Traumatic Conditions

The majority of traumatic injuries seen in patients with AS fit the extension-distraction pattern and are commonly due to the patients’ falling forward.34

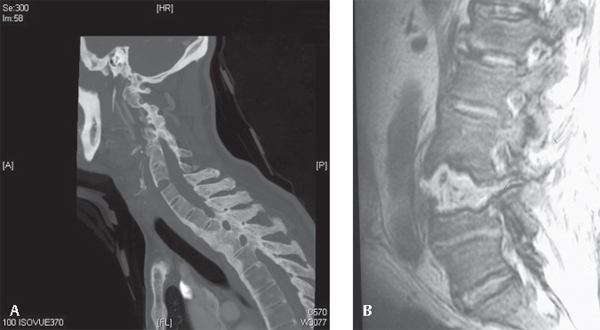

These injuries can be extremely unstable, and dislocations can occur even as the patient lies in bed. Due to the pre-existing kyphotic deformity, the weight of the patient’s head and upper body may cause increased extension of the injury unless these areas are properly supported. Immobilization of the spine should reflect the preinjury posture. Fusion and increased stiffness at the cervicothoracic junction makes fractures at C7–T1 common.22 The cervical spine should not be forced into neutral position to fit the cervical collar.35 Patients with thoracolumbar injuries are best placed on their side in bed or supine with good support under the head and shoulders (Fig. 25.3A,B).

Surgical stabilization of AS fractures should take into account the presence of long ankylosed segments above and below the fracture. This would concentrate the physiologic stresses at the fracture level and stabilizing construct. Therefore, rigid, long-segment and multiple-point fixations are recommended. In the cervical spine, anterior and posterior fixation36 or long posterior fixation constructs are recommended (Fig. 25.4A,B).

Thoracolumbar fractures are best stabilized using long-segment pedicle screw fixation.37 Percutaneous screw fixation with or without focal decompression can be very helpful in minimizing the surgical time, blood loss, and postoperative wound complications.

Epidural hematoma and delayed neurological deterioration are a real concern in patients with AS.27,38

Patients with AS who have spinal stenosis are at risk of developing cauda equina syndrome. This should be treated as a surgical emergency and treated with emergent decompression.36

Fig. 25.3 (A) Radiograph showing a three-column injury of the cervical spine. (B) MRI: T2-weighted images demonstrating an extension-pattern three-column injury of the lumbar spine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree