Chapter 18 Amputations of the Upper Extremity

Amputations should be considered the start of rehabilitation. Major amputations of the upper extremity (other than digital amputations) account for 3% to 15% of all amputations and are approximately 20 times less common than amputations of the lower extremity. Trauma is the most common reason for upper extremity amputations except for shoulder disarticulation and forequarter amputations, for which malignant tumors are the primary reasons. Generally, all possible length should be preserved in upper extremity amputations. Length preservation can be maintained by careful evaluation and lengthening of a short stump by distraction osteogenesis (the method of Ilizarov) and microvascular anastomosis. Distal-free flaps and spare-part flaps (fillet flaps) from the amputated limb also should be used to preserve length. However, prosthetists are able to fit even small stumps with prostheses to improve function. Often a small stump distal to the elbow can be functionally better than a long above-elbow amputation. A prosthetic limb cannot adequately replace the sensibility of the hand, and the function of a prosthetic limb decreases with higher levels of amputation. Few patients with amputations around the shoulder are regular prosthetic users. The use of a rigid dressing and subsequent early temporary prosthetic fitting in patients with transhumeral or more distal amputations encourages the resumption of bimanual activities, softens the psychological blow of limb loss, and decreases the prosthetic rejection rate. After 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively the soft tissues have healed significantly and the edema should be controlled enough to proceed with a definitive socket for the patient. A myoelectrical prosthesis may be an option for patients with a below-elbow amputation. However, in manual workers a more traditional device should be employed. Some institutions use hybrid systems consisting of a locking shoulder joint with a body-powered elbow and externally powered wrist and terminal devices. These systems are most useful in amputations of the dominant extremity. Recipients use the prosthesis for approximately 14 hours a day. Some reports indicate, however, that 50% of patients discontinue the use of the prosthesis after 5 years. Various terminal devices are available and are easily interchanged (Fig. 18-1). Regardless, experienced prosthetists are invaluable in ensuring that patients have proper functional devices, and they should be consulted, when available, for each patient.

Wrist Amputations

Amputation at the Wrist

Fashion a long palmar and a short dorsal skin flap in a ratio of 2 : 1. Dissect the flaps proximally to the level of proposed bone section, and expose the underlying soft structures.

Fashion a long palmar and a short dorsal skin flap in a ratio of 2 : 1. Dissect the flaps proximally to the level of proposed bone section, and expose the underlying soft structures.

Draw the tendons of the finger flexors and extensors distally, divide them, and allow them to retract into the forearm.

Draw the tendons of the finger flexors and extensors distally, divide them, and allow them to retract into the forearm.

Identify the tendons of the wrist flexors and extensors, free their insertions, and reflect them proximal to the level of bone section. Identify the median and ulnar nerves and the fine filaments of the radial nerve. Draw the nerves distally, and section them well proximal to the level of amputation so that their ends retract well above the end of the stump.

Identify the tendons of the wrist flexors and extensors, free their insertions, and reflect them proximal to the level of bone section. Identify the median and ulnar nerves and the fine filaments of the radial nerve. Draw the nerves distally, and section them well proximal to the level of amputation so that their ends retract well above the end of the stump.

Just proximal to the level of intended bone section, clamp, ligate, and divide the radial and ulnar arteries, and divide the remaining soft tissues down to bone.

Just proximal to the level of intended bone section, clamp, ligate, and divide the radial and ulnar arteries, and divide the remaining soft tissues down to bone.

Transect the bones with a saw, and rasp all rough edges to form a smooth, rounded contour.

Transect the bones with a saw, and rasp all rough edges to form a smooth, rounded contour.

At convenient points in line with their normal insertions, anchor the tendons of the wrist flexors and extensors to the remaining carpal bones so that active wrist motion is preserved.

At convenient points in line with their normal insertions, anchor the tendons of the wrist flexors and extensors to the remaining carpal bones so that active wrist motion is preserved.

With interrupted nonabsorbable sutures, close the subcutaneous tissue and skin at the end of the stump, and insert a rubber tissue drain or a plastic tube for suction drainage.

With interrupted nonabsorbable sutures, close the subcutaneous tissue and skin at the end of the stump, and insert a rubber tissue drain or a plastic tube for suction drainage.

Disarticulation of the Wrist

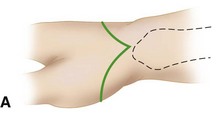

Fashion a long palmar and a short dorsal skin flap (Fig. 18-2A). Begin the incision 1.3 cm distal to the radial styloid process, carry it distally and across the palm, and curve it proximally to end 1.3 cm distal to the ulnar styloid process.

Fashion a long palmar and a short dorsal skin flap (Fig. 18-2A). Begin the incision 1.3 cm distal to the radial styloid process, carry it distally and across the palm, and curve it proximally to end 1.3 cm distal to the ulnar styloid process.

Form a short dorsal skin flap by connecting the two ends of the palmar incision over the dorsum of the hand; atypical flaps may be fashioned, if necessary, to avoid amputation at a higher level. Reflect the skin flaps together with the subcutaneous tissue and fascia proximally to the radiocarpal joint.

Form a short dorsal skin flap by connecting the two ends of the palmar incision over the dorsum of the hand; atypical flaps may be fashioned, if necessary, to avoid amputation at a higher level. Reflect the skin flaps together with the subcutaneous tissue and fascia proximally to the radiocarpal joint.

Just proximal to the joint, identify, ligate, and divide the radial and ulnar arteries.

Just proximal to the joint, identify, ligate, and divide the radial and ulnar arteries.

Identify the median, ulnar, and radial nerves and gently draw them distally into the wound. Section them so that they retract well proximal to the level of the amputation.

Identify the median, ulnar, and radial nerves and gently draw them distally into the wound. Section them so that they retract well proximal to the level of the amputation.

At a proximal level, divide all tendons and allow them to retract into the forearm.

At a proximal level, divide all tendons and allow them to retract into the forearm.

Incise the wrist joint capsule circumferentially, completing the disarticulation (Fig. 18-2B and C).

Incise the wrist joint capsule circumferentially, completing the disarticulation (Fig. 18-2B and C).

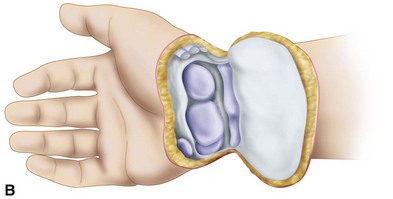

Resect the radial and ulnar styloid processes, and rasp the raw ends of the bones to form a smoothly rounded contour. Take care to avoid damaging the distal radioulnar joint, including the triangular ligament, so that normal pronation and supination of the forearm are preserved and pain in the joint is prevented (Fig. 18-2D).

Resect the radial and ulnar styloid processes, and rasp the raw ends of the bones to form a smoothly rounded contour. Take care to avoid damaging the distal radioulnar joint, including the triangular ligament, so that normal pronation and supination of the forearm are preserved and pain in the joint is prevented (Fig. 18-2D).

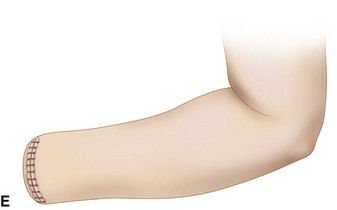

With interrupted nonabsorbable sutures, close the skin flaps over the ends of the bones (Fig. 18-2E), and insert a rubber tissue drain or a plastic tube for suction drainage.

With interrupted nonabsorbable sutures, close the skin flaps over the ends of the bones (Fig. 18-2E), and insert a rubber tissue drain or a plastic tube for suction drainage.

FIGURE 18-2 Disarticulation of the wrist. A, Skin incision. B and C, Reflection of the palmar flap and section of wrist joint capsule. D, Resection of tips of radial and ulnar styloids with preservation of the triangular ligament and underlying joint space. E, Completed amputation. SEE TECHNIQUE 18-2.

Forearm Amputations (Transradial)

Distal Forearm (Distal Transradial) Amputation

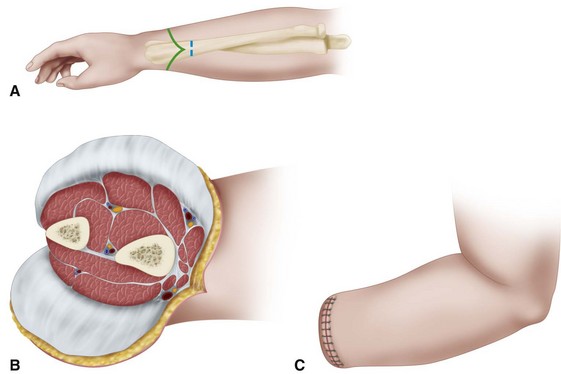

Beginning proximally at the intended level of bone section, fashion equal anterior and posterior skin flaps (Fig. 18-3A); make the length of each about equal to one half of the diameter of the forearm at the level of amputation. Together with the skin flaps, reflect the subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia proximally to the level of bone section.

Beginning proximally at the intended level of bone section, fashion equal anterior and posterior skin flaps (Fig. 18-3A); make the length of each about equal to one half of the diameter of the forearm at the level of amputation. Together with the skin flaps, reflect the subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia proximally to the level of bone section.

Clamp, doubly ligate, and divide the radial and ulnar arteries just proximal to this level.

Clamp, doubly ligate, and divide the radial and ulnar arteries just proximal to this level.

Identify the radial, ulnar, and median nerves; draw them gently distally; and transect them high so that they retract well proximal to the end of the stump.

Identify the radial, ulnar, and median nerves; draw them gently distally; and transect them high so that they retract well proximal to the end of the stump.

Cut across the muscle bellies transversely distal to the level of bone section, and allow their ends to retract to that level.

Cut across the muscle bellies transversely distal to the level of bone section, and allow their ends to retract to that level.

Divide the radius and ulna transversely, and rasp all sharp edges from their ends (Fig. 18-3B).

Divide the radius and ulna transversely, and rasp all sharp edges from their ends (Fig. 18-3B).

Close the deep fascia with fine absorbable sutures and the skin flaps with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures (Fig. 18-3C), and insert deep to the fascia a rubber tissue drain or, if preferable, a plastic tube for suction drainage.

Close the deep fascia with fine absorbable sutures and the skin flaps with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures (Fig. 18-3C), and insert deep to the fascia a rubber tissue drain or, if preferable, a plastic tube for suction drainage.

If desired, a myoplastic closure may be done in this amputation as follows. After raising appropriate flaps of skin and fascia, fashion an anterior flap of flexor digitorum sublimis muscle long enough so that its end can be carried around the end of the bones to the deep fascia dorsally.

If desired, a myoplastic closure may be done in this amputation as follows. After raising appropriate flaps of skin and fascia, fashion an anterior flap of flexor digitorum sublimis muscle long enough so that its end can be carried around the end of the bones to the deep fascia dorsally.

Divide the remaining soft tissues transversely at the level of bone section.

Divide the remaining soft tissues transversely at the level of bone section.

After dividing the bones and contouring their ends, carry the muscle flap dorsally, and suture its end to the deep fascia over the dorsal musculature. To prevent excessive bulk, the entire anterior muscle mass should never be used in this manner.

After dividing the bones and contouring their ends, carry the muscle flap dorsally, and suture its end to the deep fascia over the dorsal musculature. To prevent excessive bulk, the entire anterior muscle mass should never be used in this manner.

Proximal Third of Forearm (Proximal Transradial) Amputation

When good skin is available, fashion anterior and posterior skin flaps of equal length; if good skin is unavailable, fashion atypical flaps as necessary rather than amputate at a more proximal level. Reflect proximally to the level of intended bone section the deep fascia together with the skin flaps.

When good skin is available, fashion anterior and posterior skin flaps of equal length; if good skin is unavailable, fashion atypical flaps as necessary rather than amputate at a more proximal level. Reflect proximally to the level of intended bone section the deep fascia together with the skin flaps.

Just proximal to this level, identify, doubly ligate, and divide the major vessels.

Just proximal to this level, identify, doubly ligate, and divide the major vessels.

Identify the median, ulnar, and radial nerves; gently pull them distally; and section them proximally so that their ends retract well proximal to the end of the stump.

Identify the median, ulnar, and radial nerves; gently pull them distally; and section them proximally so that their ends retract well proximal to the end of the stump.

Divide the muscle bellies transversely distal to the level of bone section so that their proximal ends retract to that level. Carefully trim away all excess muscle.

Divide the muscle bellies transversely distal to the level of bone section so that their proximal ends retract to that level. Carefully trim away all excess muscle.

Divide the radius and ulna transversely, and smooth their cut edges. If the end of the stump is not at least distal to the insertion of the biceps tendon, resect the distal 2.5 cm of this tendon according to the technique of Blair and Morris. This lengthens the stump functionally and enhances prosthetic fitting. Even without biceps function, the elbow can be flexed satisfactorily by the brachialis muscle.

Divide the radius and ulna transversely, and smooth their cut edges. If the end of the stump is not at least distal to the insertion of the biceps tendon, resect the distal 2.5 cm of this tendon according to the technique of Blair and Morris. This lengthens the stump functionally and enhances prosthetic fitting. Even without biceps function, the elbow can be flexed satisfactorily by the brachialis muscle.

With interrupted absorbable sutures, close the deep fascia; with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures, close the skin edges. Insert deep to the fascia a rubber tissue drain or a plastic tube for suction drainage.

With interrupted absorbable sutures, close the deep fascia; with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures, close the skin edges. Insert deep to the fascia a rubber tissue drain or a plastic tube for suction drainage.