Chapter 26 Benign/Aggressive Tumors of Bone

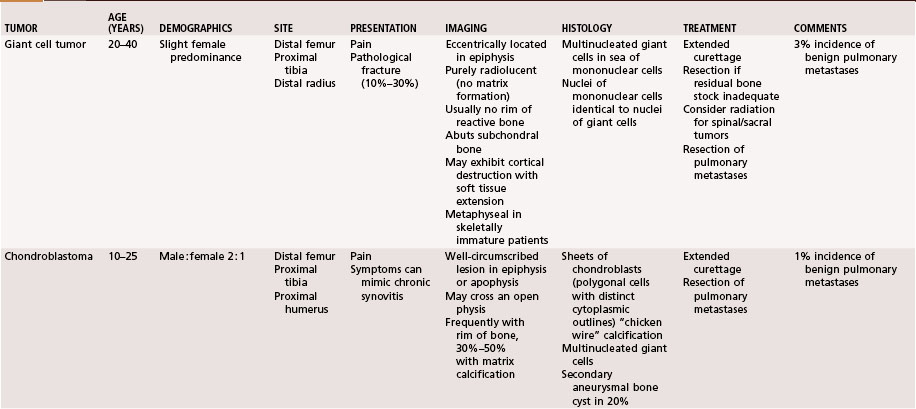

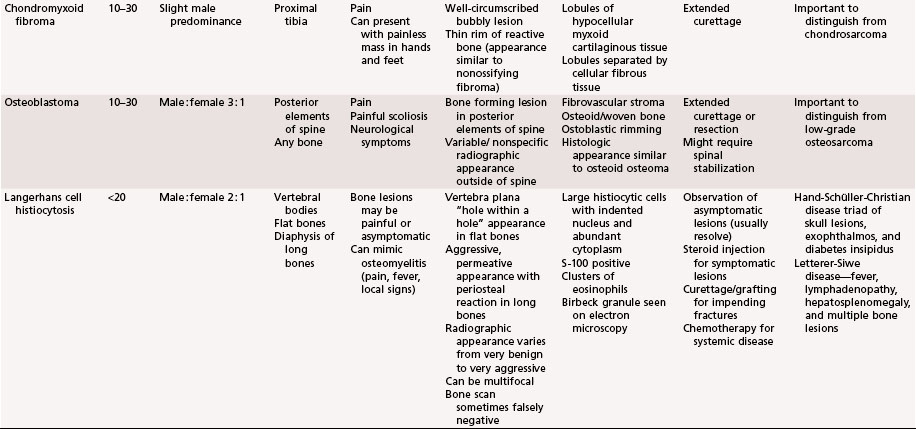

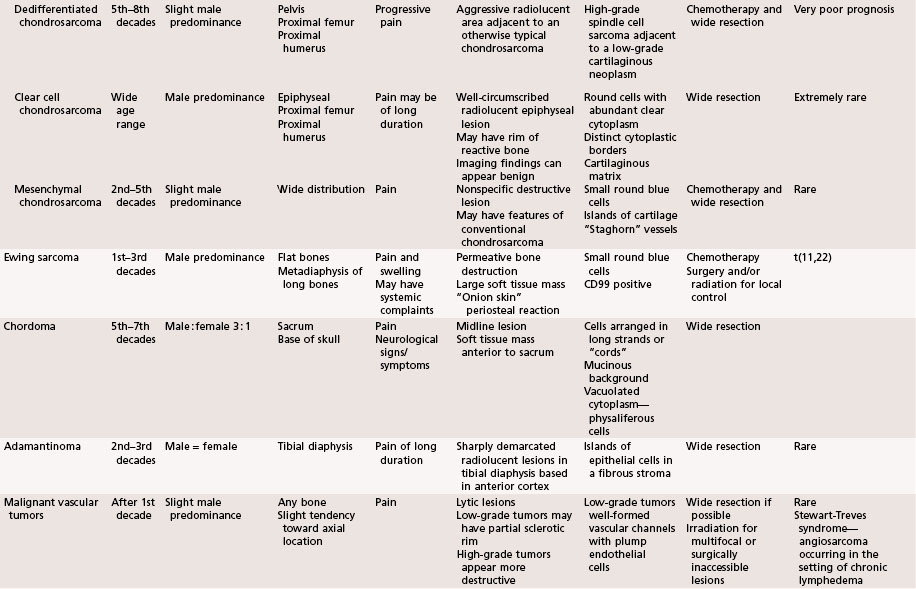

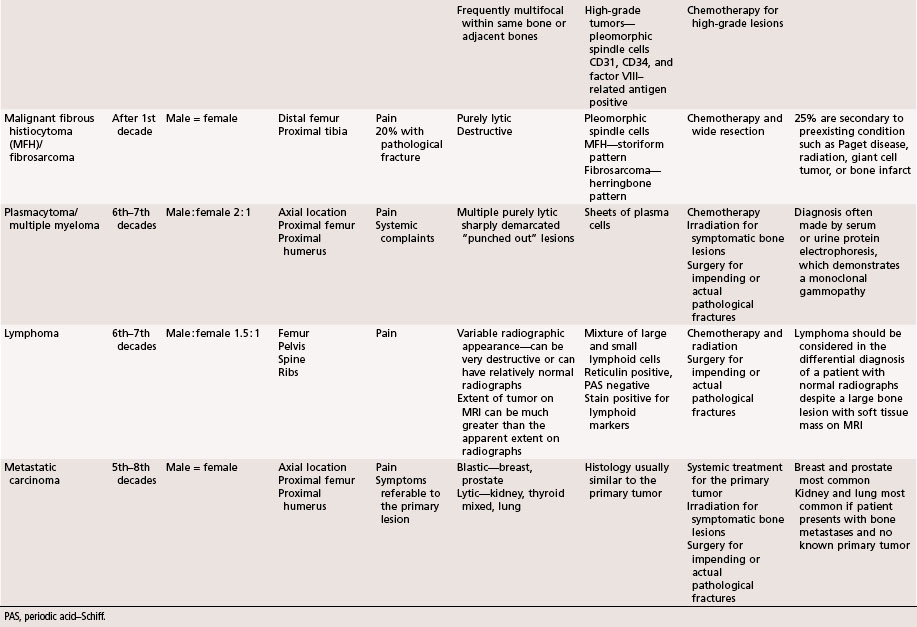

The aggressiveness of the lesions described in this chapter is between purely benign and frankly malignant. Although these lesions frequently are treated satisfactorily with intralesional procedures, such as curettage, they are sometimes very aggressive locally and require marginal or wide resection. Systemic involvement, although rare, must be evaluated and treated. Giant cell tumors and chondroblastomas can develop pulmonary metastases and rarely can be fatal. Langerhans cell histiocytosis can involve multiple organ systems in addition to bone involvement and likewise rarely can be fatal. This chapter briefly describes the clinical, radiographic, and pathological features of these lesions. A summary table is provided at the end of the chapter for a quick reference (Table 26-1).

Giant Cell Tumor

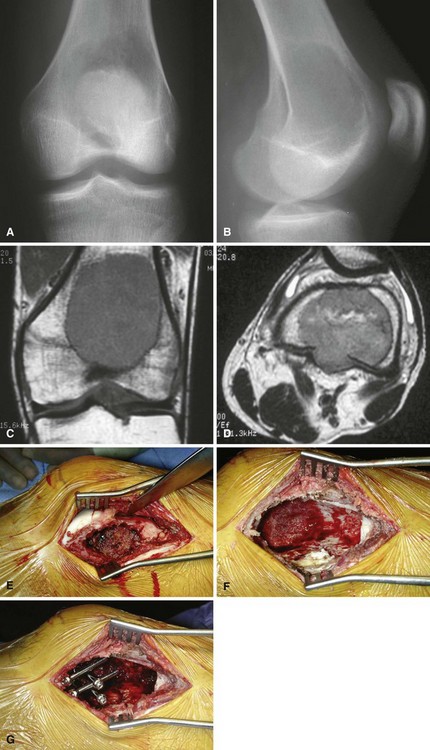

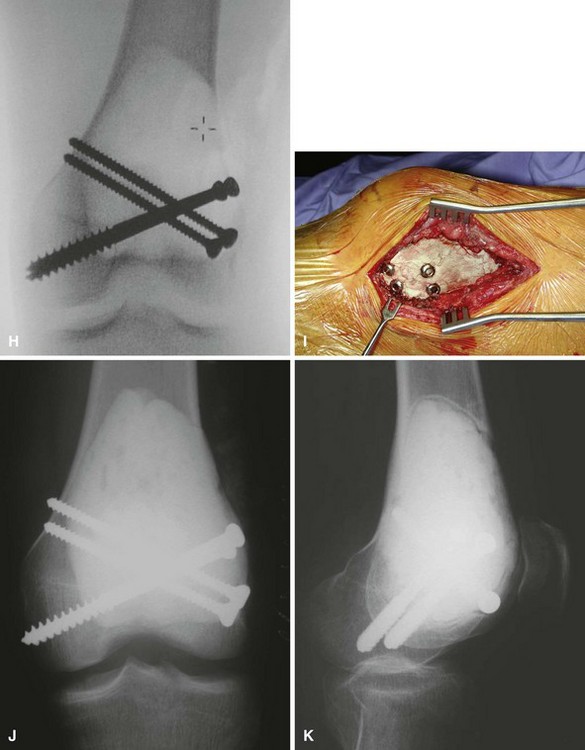

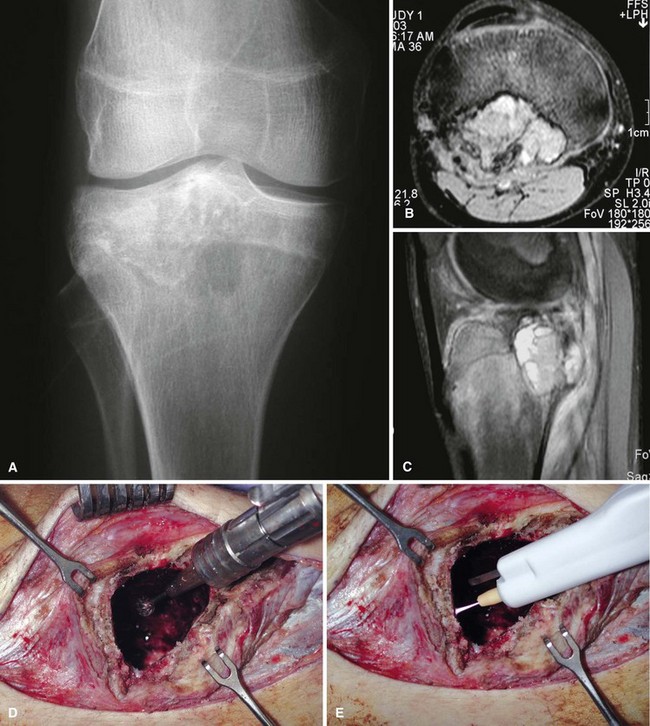

We treat most giant cell tumors with aggressive, extended curettage followed by argon beam coagulation, which is easy to use, effective, and associated with few complications. We do not use phenol or liquid nitrogen as adjuvant treatment because of potential complications, such as pathological fracture, wound healing problems, and nerve injury. We routinely use bone cement to fill the cavity because of its ease of application, immediate structural support, and ease with which local recurrence can be detected adjacent to the cement mantle. We frequently use screws placed in a crossed (Fig. 26-1) or divergent (Fig. 26-2) pattern to augment the cement mantle. Biomechanical studies performed at our institution have shown this method to significantly increase the strength of the reconstruction.

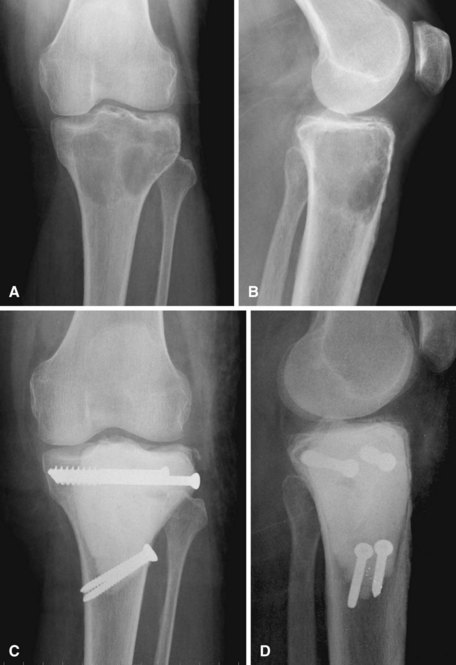

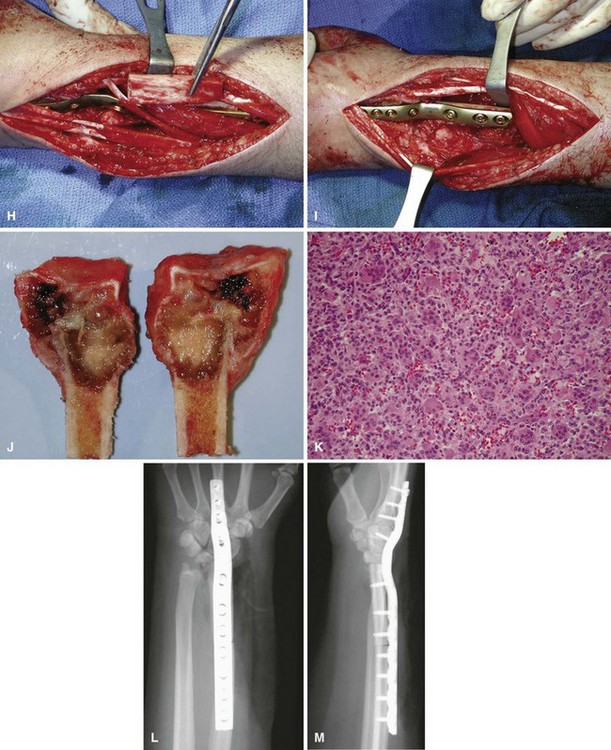

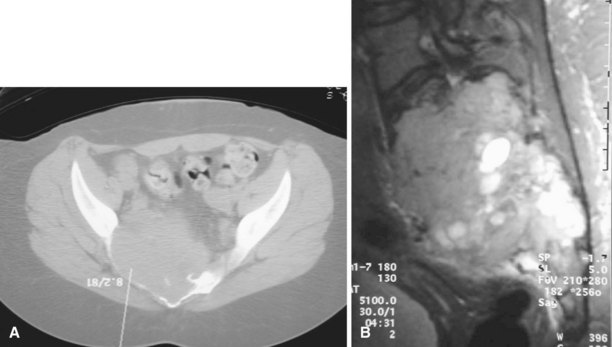

Curettage may not be effective in some stage 3 tumors, and primary resection may be required after biopsy. Around the knee, a hemicondylar osteoarticular allograft reconstruction or a rotating hinge endoprosthesis may be necessary. For aggressive lesions of the distal radius, primary resection and reconstruction with a proximal fibular autograft (either as an arthroplasty or as an arthrodesis) may be indicated (Fig. 26-3). For lesions in expendable bones (e.g., the distal ulna or proximal fibula), primary resection without reconstruction may be indicated. For inoperable lesions in the spine or pelvis, irradiation or embolization (or both) may be used (Fig. 26-4); however, caution is advised because of the risk of sarcomatous change in patients treated by irradiation. In patients with pulmonary metastases, resection should be attempted. Chemotherapy has limited success, and irradiation should be reserved for symptomatic inoperable lesions.

Chondroblastoma

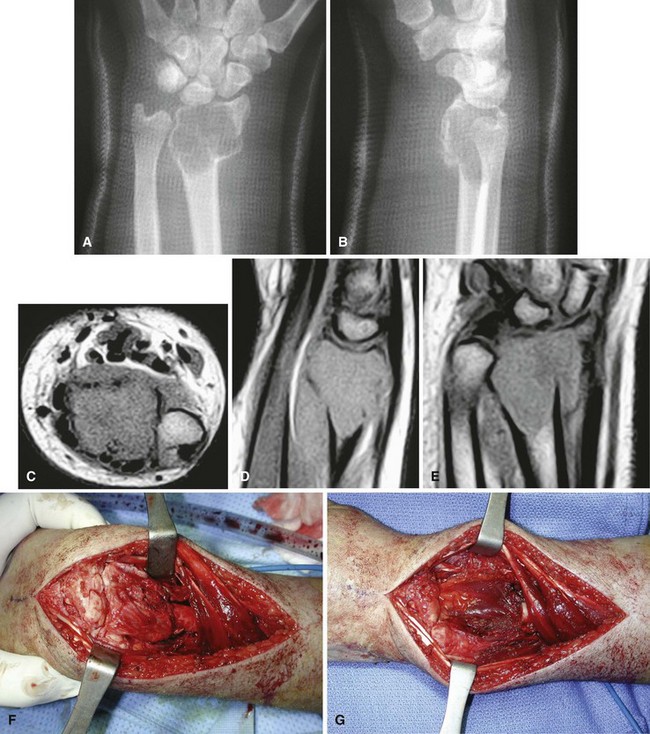

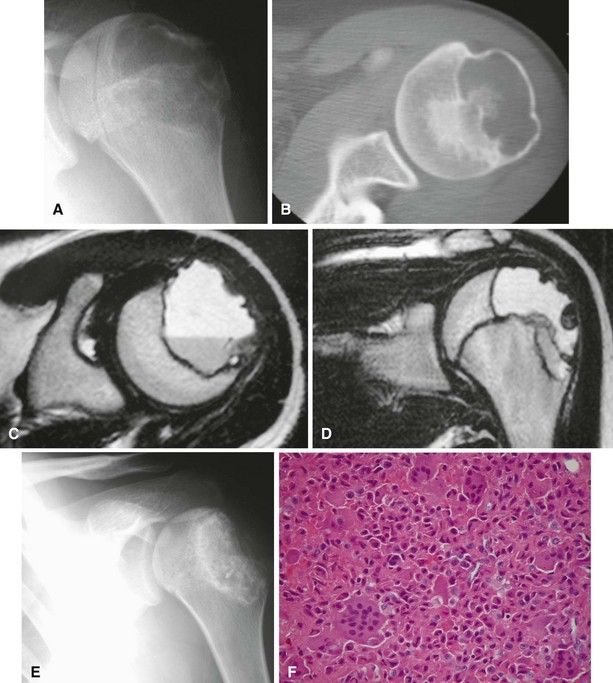

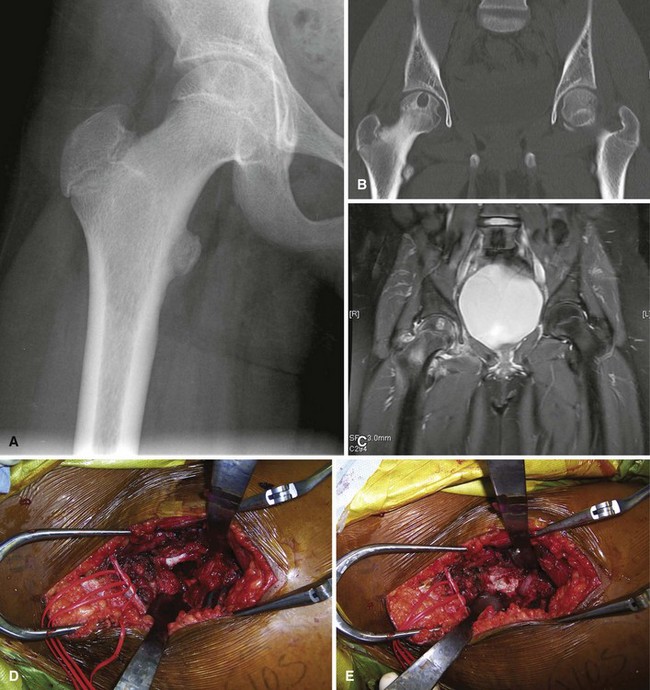

Radiographic findings usually are characteristic. This well-circumscribed lesion usually is centered in an epiphysis of a long bone; however, it also may be located in an apophysis, such as the greater tuberosity (Fig. 26-5) or the greater trochanter (Fig. 26-6). Often it has a surrounding rim of reactive bone (Fig. 26-7), and 30% to 50% exhibit matrix calcification. CT can be helpful to detect subtle areas of calcification that may or may not be detectable on plain radiographs. MRI frequently demonstrates abundant surrounding edema. Soft tissue extension is extremely rare. In children, a well-circumscribed epiphyseal lesion that crosses an open growth plate is highly suggestive of chondroblastoma but could also represent an infectious process. For adults, differential diagnoses for an epiphyseal lesion include giant cell tumor and clear cell chondrosarcoma. In contrast to chondroblastomas, however, giant cell tumors usually do not have a rim of sclerotic bone or intralesional calcification and may have a soft tissue component.

Chondroblastomas usually present as stage 2 and, more rarely, as stage 3 lesions. Although they typically are not as aggressive as giant cell tumors, surgical management is warranted for almost all chondroblastomas owing to the slowly progressive nature of the disease. Treatment consists of extended curettage and bone grafting or placement of bone cement. Adequate curettage always should take precedence over sparing the physis (Fig. 26-8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree