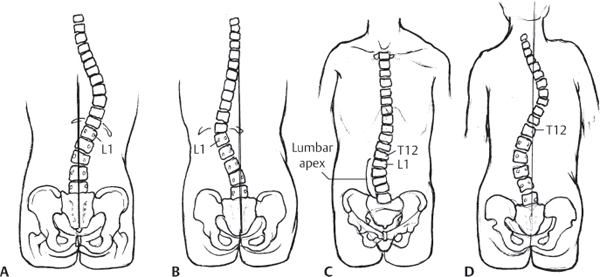

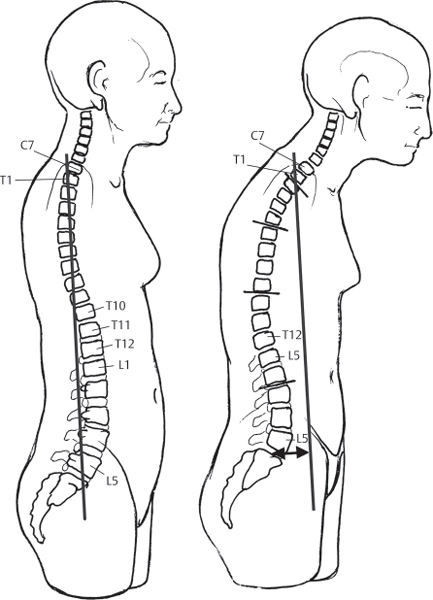

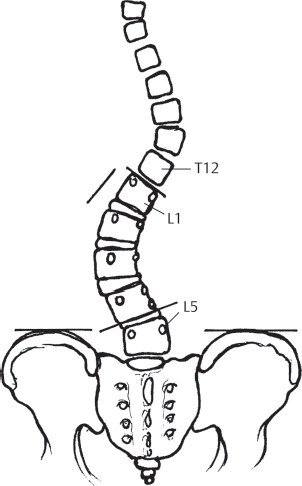

41 Adults with scoliosis often have rigid curves with coexistent degenerative disk disease, spinal stenosis, and osteopenia. As a result, surgical treatment of adult scoliosis tends to be more complex than for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. The goals of surgical intervention include a fused, stable spine with the head centered over the sacrum, relief of pain, improvement of cosmesis, and prevention of deformity progression. Adult scoliosis can be divided into idiopathic and degenerative types. In adult idiopathic scoliosis, the curvature begins prior to skeletal maturity and progresses with age. Patients over the age of 40 with pre-existing idiopathic scoliosis develop degenerative changes that contribute to both the deformity and the clinical symptoms. In contrast to the well-accepted classification systems for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, there are no universally accepted radiographic parameters or classification schemes for adult scoliosis. As defined by the Scoliosis Research Society, curves with an apex from T2 to the T11–T12 disk space are classified as thoracic. Curves with an apex from T12 to L1 are classified as thoracolumbar, and curves with an apex from the L1–L2 disk to the L4–L5 disk are considered lumbar (Fig. 41.1). The Adult Deformity Classification proposed by Schwab et al. divides the thoracic curve into either upper or lower thoracic and adds sagittal balance, lumbar lordosis, and subluxation modifiers.1 The Scoliosis Research Society adult scoliosis classification scheme builds upon the Lenke and King/Moe classification systems and includes modifiers for sagittal and coronal balance, olisthesis, and lumbar degenerative disk disease.2 In degenerative scoliosis, the deformity typically develops in an elderly patient without preexisting spinal deformity. Degenerative change in the setting of osteopenia is the primary cause of the deformity. Degenerative curves typically involve the lumbar spine and demonstrate loss of lumbar lordosis, a lateral tilt at L4–L5, and rotatory subluxation at L3–L4. The thoracic spine often does not display a compensatory curve in degenerative scoliosis.3 Fig. 41.1 There are four adult idiopathic scoliosis patterns: (A) Single thoracic. (B) Thoracolumbar. (C) Lumbar. (D) Double major. Adults with scoliosis often present with back pain and neurogenic pain (claudication or radicular) in addition to dissatisfaction with physical appearance. It is important to determine whether pain is the result of the deformity or related to neural compression. Axial pain can be related to muscle fatigue, degenerative disk disease, or facet arthrosis. Coexisting central or foraminal stenosis can cause neurogenic claudication or radicular leg pain. Symptoms of radiculopathy, if present, usually occur on the concave side of the lumbar curve. The patient is asked to stand straight and is viewed from four directions. From the anterior and posterior viewpoints, the balance of the head and trunk over the pelvis and the relative heights of the iliac crests and shoulders are noted. Viewed from the side, loss of lumbar lordosis and hip or knee flexion should be noted as signs of sagittal imbalance. The patient is then asked to bend forward, and the appearance of a thoracic hump or lumbar asymmetry is noted. A thorough neurologic examination completes the physical examination. To assess spinal deformity radiographically, standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the entire spine are taken on long 36-inch cassettes. Cobb angle measurements of all curves and pelvic obliquity are determined. Vertical plumb lines are drawn on the AP and lateral radiographs to determine coronal and sagittal plane balance (Fig. 41.2). Bending views to assess curve flexibility are helpful for surgical decision making and preoperative planning. The neutral and stable vertebrae are identified on standing and bending films. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or diskography can be used to assess the condition of the distal lumbar disks and to help define the proper level for ending the fusion construct. MRI is especially helpful in cases with coexisting neurogenic claudication or radiculopathic symptoms. Fig. 41.2 On a lateral radiograph of the spine balanced in the sagittal plane, a vertical plumb line from the center of the C7 body should fall through the L5–S1 disk. The deviation of the plumb line from the center of the L5–S1 disk represents the positive or negative sagittal imbalance (double arrow). Treatment for most adult patients with scoliosis consists of conservative measures to decrease symptoms. This includes activity modification, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and occasionally non-structural bracing. A systematic literature review showed very weak evidence of efficacy for physical therapy, chiropractic treatment, and bracing.4 Surgery is indicated for patients who continue to have severe pain despite adequate conservative therapy or who demonstrate significant curve progression with coronal or sagittal plane imbalance. hSeveral key principles should be kept in mind when treating adult scoliosis operatively.5 The stable and neutral vertebrae should be included in the caudal and cephalad extents of the fusion. In the sagittal plane, the fusion should never end at the apex of the thoracic kyphosis. to avoid progressive junctional kyphosis. Strong consideration should be given to anterior structural grafting when extending a long construct to the sacrum (spanning to above L3), to prevent pseudarthrosis. Patients with curves of less than 70° can usually be treated satisfactorily with posterior instrumentation and fusion. In larger curves with ankylosis or severe facet arthrosis, a combined procedure will likely produce a better correction, solid fusion, and achievement of balance. Anterior correction and segmental instrumention can provide optimal fusion rates and outcomes in relatively young patients with mild to moderate thoracolumbar and lumbar curves (< 50 degrees) and flexible compensatory curves above and below the deformity. A posterior-only approach is indicated if decompression is required for stenosis or radiculopathy. Combined approaches are indicated in patients with poor bone stock and rigid deformities > 50 degrees. Instrumentation should not stop at the thoracolumbar junction or the midthoracic spine due to the possibility of junctional kyphosis.6 Balanced curves less than 60 degrees can be treated with posterior-only instrumentation and fusion. With larger and more rigid curves, a combined approach should be strongly considered. In lumbar scoliosis with a significant rigid lumbosacral curve greater than 15 degrees, fusion to S1 is indicated. Correction of more cephalad curves can result in iatrogenic imbalance if a significant lumbosacral curve is not addressed. Iliac screws or an anterior structural graft may be necessary to obtain a biomechanically sound construct. Fusion to S1 can be avoided if the L5–S1 disk height is maintained, there is no stenosis at L5–S1, and the disk space opens both ways on bending films.7 Treatment of degenerative scoliosis is based on patient symptoms, curve magnitude and flexibility, presence of rotatory subluxation, and the presence of coronal or sagittal imbalance.8 In keeping with the principles of idiopathic scoliosis treatment, fusions should begin and end with the neutral and stable vertebra and not end at a level with junctional kyphosis or rotatory subluxation. Typically, adult degenerative scoliosis presents with L3–L4 rotatory subluxation, L4–L5 tilt, and L5–S1 disk degeneration producing lumbar back pain with or without leg pain (Fig. 41.3). Operative levels should include the end vertebrae used in determining the Cobb angle and extending to L5 when there is significant listhesis present. Fusion should be extended to S1 in the presence of L5–S1 spondylolisthesis, previous L5–S1 laminectomy, central or foraminal stenosis at L5–S1, oblique takeoff of L5, or severe degenerative disk changes at L5–S1. In long fusions, instrumentation with iliac screws or anterior structural grafting should be considered. Fig. 41.3 Degenerative scoliosis curves are usually lumbar and have a characteristic lateral tilt at L4–L5, rotatory subluxation at L3–L4, and sequelae of degenerative disk disease.

Adult Scoliosis

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Imaging

![]() Treatment

Treatment

![]() Treatment of Adult Idiopathic Scoliosis

Treatment of Adult Idiopathic Scoliosis

Single Thoracic Curves

Single Thoracolumbar and Single Lumbar Curves

Double Thoracic and Lumbar Curves

Lumbosacral Fractional Curves

![]() Treatment of Degenerative Scoliosis

Treatment of Degenerative Scoliosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree