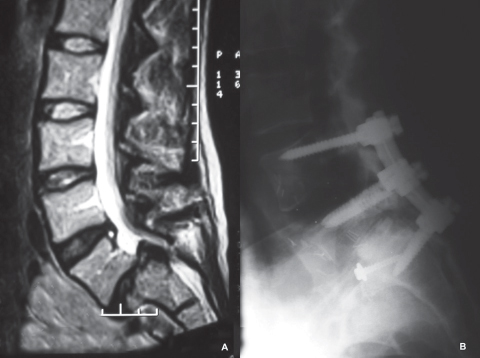

33 Adult isthmic spondylolisthesis (AIS), a subluxation of a vertebral body (VB) over a subadjacent VB, occurs in 6% of the general population.1 Although the etiology of AIS is unclear, a genetic basis for isthmic spondylolisthesis is supported by the observation that familial incidence is 25–30%.2 Acute fatigue-induced spondylolytic lumbosacral stress fractures are also implicated in isthmic spondylolisthesis. Pelvic lordosis correlates with both incidence of AIS and degree of vertebral slip. Regardless of the mechanism, an established defect in the pars interarticularis, or isthmus, progresses to a frank slippage as anatomic and biomechanical forces compromise bone repair. Biomechanical complications arise from forward forces on the spinal axis, and paraspinal muscle strain occurs from prolonged compensation of misaligned sagittal balance. The incidence of slip progression in the asymptomatic adult patient is 5%, with the overall likelihood of progression decreasing with age.1 Neurologic sequelae arise from changing spinal canal dimensions or compromise of the neural foramina. The most common location of a pars defect is at L5, which accounts for 90% of cases. This results in subluxation at the L5–S1 level.2 The incidence of spondylolysis in adult high-level athletes (8%) is comparable to that in the general population. Conversely, athletes who participate in throwing sports, gymnastics, rowing, weight lifting, and swimming are found to have higher incidences of spondylolysis.3 Three types of AIS have been described.2 Subtype A is the classic lytic-fatigue pars lesion. Subtype B is an elongated, but intact isthmus, representing a healed fracture. Subtype C is an acute fracture of the pars. Grading of spondylolisthesis on the lateral radiograph had been proposed by Myerding as follows: grade 1, 1–24% slip; grade II, 25–49% slip; grade III, 50–74% slip; grade IV, 75–99% slip; grade V, 100% to greater. Angular displacement, expressed as sagittal rotation or slip angle, determines the degree of lumbosacral kyphosis.2,4 Isthmic spondylolisthesis is commonly considered a pediatric condition; however, it is becoming more common in adults. Low back pain is typically the initial presenting symptom with adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. Individuals usually remain asymptomatic even with pars defects with or without low-grade spondylolisthesis. It is not until adulthood that some will become symptomatic and seek treatment. Pain may be discogenic or due to the hypermobility at the slip site. As the index disk degenerates and the slip progresses, associated symptoms such as radiculopathy or neurogenic claudication may develop. An extensive description of back pain should be captured, particularly the location, chronicity, severity, and quality. Neurogenic claudication or radicular symptoms may be present. Vascular insufficiency and peripheral neuropathy need to be ruled out as alternative causes for symptoms. Subluxation of grade II or greater may result in angular displacement and lumbosacral kyphosis. In such cases, patients present with lumbar hyperextension, pelvic rotation, and hamstring tightness. High-grade slips can also be associated with cauda equina symptoms or radicular complaints. Physical examination may reveal a palpable abnormality over the L4–L5 spinous process junction where the L5 arch is stationary and the L4 arch displaces anteriorly with the L5 VB. Plain-film radiographs for visualizing isthmic spondylolisthesis include lateral, anteroposterior, and oblique views to reveal pars architecture and the relative positions of vertebral bodies. Dynamic radiographs reveal the amount of translation and angulation. Axial computed tomography (CT) scans are the best for visualizing bony neural arch architecture. They are highly sensitive for spondylolysis and are very useful for assessing healing or chronic pars abnormalities. They can also help assess facet tropism and orientation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is less useful for identifying the pars defect. However, MRI allows for assessment of central canal and neural foraminal narrowing and is commonly used to determine the need for decompression and fusion. Bone scans are useful in identifying acute pars or acute stress fractures, which are characterized by increased contrast uptake at the affected sites. Single-photon-emission CT has been shown to be more sensitive and superior to MRI and technetium-99m bone scanning. It can be used as a tool to monitor healing during bracing.1 Nonsurgical options include activity modification, bracing, physical therapy, and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), selective nerve root blocks, or pars injections. Few studies have rigorously analyzed conservative care in the treatment of this population, and treatments generally follow recommendations for nonsurgical management of nonspecific low back pain. Flexible pelvic tilt (PT) has been shown to be superior to extension-based PT in achieving symptomatic relief. After 3–6 months of successful treatment with the use of antilordotic bracing and activity modification, over 75% of adults presenting with symptomatic grade I or grade II spondylolisthesis improve (Fig. 33.1).1 Surgical intervention criteria, following failure to respond to 6 months of nonsurgical treatment, include progression of slippage of greater than 30%, subluxation greater than grade II, progressive neurologic symptoms, and physical deformity. The goals of surgical intervention via fusion of the affected levels are restoration of disk height; reduction of slip angle and, if possible, forward translation; improvement in sagittal alignment; and improvement of functional outcome. Direct repair of the pars defect to arrest progression of low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis or spondylolysis in younger patients has been reported.5 In the presence of radicular symptoms only, neural decompression and mobilization of exiting nerve roots by removal of the floating posterior elements and cartilaginous tissue (the Gill procedure6) has been reported. However, this approach leads to increasing postoperative subluxation in ~ 27% of cases, though clinical symptoms may not be severe.7 Decompression alone is now rarely used and is reserved for older patients with stabilizing anterior osteophytes. Fig. 33.1 (A) T2-weighted MRI demonstrating grade II spondylolisthesis, degenerative disk disease, and spinal stenosis at L5–S1, and degenerative disk changes, annular tear, and stenosis at L4–L5. (B) Postoperative (day of surgery) plain-film lateral radiograph demonstrating anterior lumbar interbody fusion cage at L4–L5, femoral ring allograft at L5–S1, decompressive laminectomy at L5–S1 (Gill procedure), with instrumented posterior fusion at L4–S1, with reduction of spondylolisthesis.

Adult Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Spinal Imaging

![]() Treatment

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree