Ankle sprains are the most common sports-associated injury, accounting for as much as 40% of all athletic injuries. It has been estimated that ankle sprains account for up to 10% of all visits to the emergency department and have an incidence of up to one inversion injury of the ankle per 30,000 people each day and 2 million per year.

Epidemiology

Sprains of the ankle occur in many sports. The incidence of ankle injuries appears to be equal among males and females when compared within specific sporting activities. The peak ages of injury range between 10 and 19 years. They account for 45% of all basketball injuries and 31% of soccer injuries. In football, 10% to 15% of all time lost to injuries is attributable to ankle injuries. One-third of all military recruits sustain an inversion ankle injury that requires medical care during a 4-year tenure.

Long-term sequelae from lateral ankle sprains have been estimated to occur in up to 60% of patients. The grade of acute ankle sprains does not correlate well with chronic symptoms. Interestingly, the factor most predictive of residual symptoms, 6 months following an ankle injury, was a syndesmosis sprain and not mechanical instability. The most common complaints in patients with chronic ankle instability are swelling, giving way, frank instability, and pain.

Anatomy

The lateral ankle is supported by both static and dynamic restraints. The static restraints are provided by the bony configuration of the ankle and the ligaments. The dynamic restraints are the peroneal tendons—longus and brevis. The shape of the joint contributes about 30% of the resistance to rotational forces about the ankle, whereas the soft tissues provide the other 70%.

The configuration of the talus, with its flared anterior half, provides a bony restraint to lateral motion when the talus is engaged in the mortise in dorsiflexion. In plantarflexion, the narrowest surface of the talus is in the mortise, rendering less bony stability and an increased risk to inversion injury.

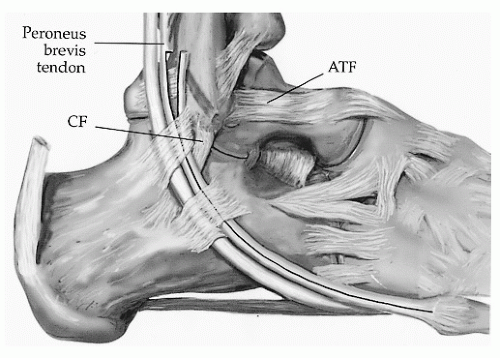

The lateral collateral ligaments of the ankle include (

Fig. 12.1) the following:

Anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) from the anterior border of the lateral malleolus to the lateral talar body

Calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) from the anterior tip of the lateral malleolus to the lateral posterior calcaneus

Posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL)

In neutral position, the ATFL runs parallel to the axis of the foot, whereas in plantarflexion, it is vertical and functions as a collateral ligament. The CFL is taut in dorsiflexion. The CFL works in concert with the ATFL and is rarely injured alone. The ATFL is the primary restraint to inversion throughout ankle plantarflexion and dorsiflexion.

At the lateral malleolus, the peroneal tendons run through a fibro-osseous tunnel under the superior peroneal retinaculum, and distally they pass deep to the inferior peroneal retinaculum. The superior peroneal retinaculum and CFL run parallel. Anteriorly, the peroneal tendons are stabilized by the posterior surface of the distal fibula in the retromalleolar sulcus. The peroneus brevis inserts on the base of the fifth metatarsal, and the peroneus longus courses under the cuboid to insert on the base of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform. The peroneals act primarily as evertors, with the peroneus brevis being the stronger of the two. The peroneal muscles work dynamically to stabilize both the ankle and the subtalar joint.