Treatment of Structural Instability in the Neuromuscular Hip

Lisa Berglund

John C. Clohisy

Perry Schoenecker

Hip instability in cerebral palsy is an acquired condition related to primary underlying muscle imbalance and secondary bony deformity (1,2,3). Patients have spasticity of their hip flexors and adductors and relative weakness of hip abductors and extensors. Weight bearing is delayed and the eventual ability for functional ambulation is variably limited. Secondarily, abnormal bony growth/remodeling about the hip joint is typically characterized by persistent relative increased femoral anteversion and/or coxa valgum (4,5). The acetabulum becomes dysplastic and the hip joint variably unstable. The incidence of hip stability is directly related to the severity of the neuromuscular involvement of the patient (1,2,3,4). In a review of over 2,000 (all with neuromuscular hip involvement) patients at the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS), the overall incidence of subluxation was 37% and dislocation 8%. In the quadriplegic patient, subluxation occurred in 38% and dislocation 15.5%. In the partially involved (hemiplegic, diplegic, monoplegic), 9.5% of the patients had subluxation and 1% dislocation (2).

In the treatment of neuromuscular hip dysplasia in the young child, soft tissue releases (adductor ± psoas recessions) can be effective in helping to re-establish relative muscle balance in hips at risk (1,2,3). For more established hip joint subluxation/dislocation, proximal femoral osteotomy (PFO), pelvic osteotomy, or both are typically necessary to correct the dysplastic hip deformities. Surgical goals are to maintain a located hip and a level pelvis to ensure the best chance for future hip stability as the patient enters adolescence and adulthood (7,8,9,10).

As patients with cerebral palsy (CP) enter adolescence/adulthood, hip instability predictably limits functional weight bearing and interferes with activities of daily life. Surgical intervention, may be indicated in the treatment of selected patients. Joint preservation surgery maintains the integrity of the native joint and minimizes risk for progressive joint degeneration. Successful neuromuscular hip joint preservation (improved flexibility and restored stability) potentiates restoration of function in ambulation and ease of performing activities of daily life. In contrast, nonambulatory CP patients may have decreased ability both in sitting and participating in transfers in part due to hip instability/subluxation. However, these patients are typically not good candidates for extensive joint preservation surgery. Rather, when indicated, a more appropriate surgical approach may include soft tissue releases, proximal valgus femoral osteotomy, and at times proximal femoral resection and/or prosthetic implant (11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19).

Clinical Presentation/Diagnosis

In the skeletally immature patient with cerebral palsy, hip instability is often painless and can present as a leg length discrepancy or limp. However, when hip instability persists into adulthood, hip deformity associated with neuromuscular hip instability often becomes painful. The presence of chronic joint subluxation, severe soft tissue contractures, and muscle spasticity all contribute to progressive and disabling hip pain even with sitting. In the ambulatory patient, early symptoms may include increasing limp secondary to abductor fatigue or mild to moderate general discomfort or ache in the region of the groin or lateral hip. As time progresses, patients often develop more localized groin pain and difficulty with weight-bearing activities even with assisted devices. Sitting also typically becomes more painful.

Examination

Physical examination should include a careful measurement of the hip range of motion (ROM), and an assessment of the severity of pain that may occur during this examination. The physical examination critical factors in determining which patients are or are not good candidates for joint preservation surgery. The hip examination in an ambulatory patient who is an appropriate candidate for joint preservation surgery is characterized by a relatively good ROM. The hip ideally will flex to 90 to 100 degrees. Internal and external rotation is assessed; typically there is excessive internal rotation deformity in association with a variable adductor contracture. A true assessment of the relative increased internal rotation (increased femoral anteversion) is best achieved with the patient examined prone (20). Passive hip abduction

and adduction motion is documented noting the degree of adductor contracture. On examination the patients should be relatively pain free with discomfort noted only at the extremes of flexion and abduction. A relative contraindication to joint preservation surgery can be noted in marked restriction in ROM and/or pain occurring throughout the ROM assessment. The hip and knee should be assessed for any flexion contractures. The spine and pelvis should be assessed for the presence of any scoliosis and associated pelvic obliquity.

and adduction motion is documented noting the degree of adductor contracture. On examination the patients should be relatively pain free with discomfort noted only at the extremes of flexion and abduction. A relative contraindication to joint preservation surgery can be noted in marked restriction in ROM and/or pain occurring throughout the ROM assessment. The hip and knee should be assessed for any flexion contractures. The spine and pelvis should be assessed for the presence of any scoliosis and associated pelvic obliquity.

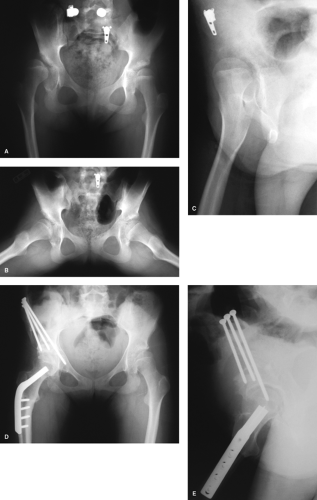

Image assessment should include anteroposterior (AP) erect pelvis, frog leg lateral, and false-profile views of both hips (Fig. 37.1A–C) (21). The AP pelvis should be assessed noting lateral head coverage (lateral center edge angle), acetabular inclination, and presence of subluxation (a break in Shenton’s line). The false profile should be used to assess the anterior femoral head coverage (anterior center-edge angle) (Fig. 37.1A–C). Often the patients have global (anterior, lateral, and posterior) acetabular deficiency. The proximal femur is assessed for both anteversion and coxa valga. The contour of the femoral head is carefully examined. Chronic subluxation of the femoral head is often associated with characteristic superior lateral femoral head notching deformity secondary to erosion into the head by the spastic gluteus minimus (22). For surgical planning, a functional AP pelvis radiograph is obtained with the patient in a supine position and an assistant holding the hips in a position of flexion, internal rotation, and abduction. This confirms the potential for both congruent reduction in the femoral head subluxation and improved femoral head coverage following either performing a redirectional pelvic or femoral (or both) osteotomy(ies). On occasion a CT scan may help quantify the pathoanatomy such as the extent and location of both the acetabular and femoral head pathomorphologies (4). Magnetic resonance imaging (specifically an MR arthrogram) usually is not part of the assessment in surgical planning as labral chondral pathology is typically not an issue.

Periacetabular Osteotomy in the Mature Neuromascular Patient

The correction obtained in skeletally immature hips with neuromuscular hip dysplasia with incomplete osteotomies relies on both an open triradiate cartilage and to some extent a relative elastic symphysis pubis (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). The same osteotomies are not consistently effective in obtaining correction of acetabular dysplasia in the skeletally mature patient. Rather, a complete cut of the pelvis is necessary to predictably obtain satisfactory redirection of the entire acetabulum.

Chiari’s single innominate osteotomy can be utilized in the skeletally mature patients in the treatment of hip instability secondary to acetabular deficiency. Several authors have noted satisfactory outcomes (resolution of pain and sustained improvement in ambulation) (23,24,25,26) following the utilization of the Chiari osteotomy, often combined with a PFO, in the treatment of patients with neuromuscular-associated hip dysplasia. Rotational acetabular osteotomies have been described to correct dysplasia in mature patients (27,28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree