Total Knee Replacement: Pearls of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Preservation

Indications

The posterior cruciate is present (although not necessarily normal) in 99% of arthritic knees undergoing total knee arthroplasty.1 The operating surgeon has the option to preserve this ligament as a biological stabilizer, or resect it and substitute for its function via a semiconstrained posterior stabilized articulating topography.

Each technique has advantages and disadvantages. The 10-year survivorship data are similar for both methods, and the choice is generally based on the operating surgeon’s training and experience. This author preserves the posterior cruciate ligament in approximately 98% of primary knee arthroplasties in both osteoarthritic and rheumatoid patients.2,3

Contraindications

The relative contraindications to posterior cruciate preservation include:

- Preoperative posterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur

- A severe flexion contracture persisting under anesthesia (greater than 45 degrees)

- A posttraumatic or postosteotomy deformity of the tibia resulting in an up-sloped joint line

- A chronically dislocated patella

- A patellectomized knee

- An ankylosed knee

- Inability of the surgeon to properly balance the flexion gap

Severe angular deformity is not a contraindication to posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) preservation unless it is associated with rotary subluxation of the tibia.

Surgical Procedure

Exposure of the knee for PCL preservation is similar to that used for cruciate substitution. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), if present, is resected and the anterior horn of the medial meniscus is removed. This gains access to the plane between the deep medial collateral ligament and the cortical rim of the medial tibial plateau. A curved 1-cm osteotome or periosteal elevator is introduced into this plane and passed posteriorly to the level of the semimembranosus bursa. The tibia can then be externally rotated and delivered in front of the femur for excellent exposure, the so-called Ransall maneuver.4 Intercondylar osteophytes are removed from the femur to define the origin of the PCL.

Bone Preparation

The kinematics of the knee are best preserved for proper PCL function by maintaining the joint line at the proper level. This is accomplished by performing measured resections from the distal and posterior femur as well as from the proximal tibia. The resection amount is based on the thickness of the prosthetic components being utilized.

Flexion/Extension Gap Balancing

In PCL preservation, it is important that bone preparation does not result in a flexion gap that is tighter than the extension gap. In such a case, one or more of the following four measures may be necessary to balance the gaps:

- Releasing the PCL

- Increasing the posterior slope of the tibial resection

- Downsizing the anteroposterior (AP) dimension of the femoral component to increase the flexion space, as long as notching the anterior femoral cortex is avoided

- Cementing the femoral component proud of the distal cuts to tighten the extension gap without affecting the flexion gap

The converse situation (tighter in extension than in flexion) is much easier to solve, usually with 2 extra millimeters of distal femoral resection.

To avoid this situation, surgeons who preserve the PCL should err toward a conservative initial distal femoral resection (unless a preoperative flexion contracture exists). Many total knee arthroplasty technique manuals are misleading when they call for 10 mm of distal femoral bone resection for a 10-mm-thick femoral component. They should specify 8 mm of bone or 10 mm if the thickness of cartilage is included in the measurement.

The above scenario with mismatched flexion and extension gaps is less likely to be a problem with cruciate substituting techniques because PCL resection increases the flexion gap relative to the extension gap.

Proximal Tibial Resection

In measured resection technique, restoration of the tibial joint line level is accomplished by removing the thickness (including cartilage) from the higher plateau that corresponds to the composite thickness of the tibial component being utilized. The higher side is almost always the periphery of the lateral plateau, even in a valgus deformity. In the presence of significant preoperative ligamentous laxity or joint line distortion from trauma or osteotomy, a more conservative initial resection is appropriate. Between 0 and 5 degrees of posterior slope is initially applied, depending on the patient’s anatomy.

Balancing the Posterior Cruciate Ligament

Once the femoral and tibial resections are completed at the appropriate angles, and the ligaments are balanced in extension, trials can be placed to assess the balance of the flexion gap and PCL with three possibilities:

- Too loose

- Too tight

- Just right

The so-called POLO test (pull out and lift off) has been suggested to accomplish PCL balancing.5

The trial components are inserted using a tibial tray with no stem and an AP curved sagittal tibial topography. Tibial tray rotational alignment is established in extension so that there is proper rotational congruity with the established femoral component rotation.

Flexion Space/Posterior Cruciate Ligament Too Loose

The knee is flexed 90 degrees and the surgeon attempts to pull out (the PO of POLO) the tray from underneath the femur. If this is easily accomplished, a thicker insert is required. Conversely, the surgeon should not be able to insert the trial femur first and slide a curved trial tibial component in underneath the femoral component.

Flexion Space/Posterior Cruciate Ligament Too Tight

Now that the flexion space is not too loose, it is tested for excessive tightness. With trials in place, the knee is flexed from 80 to 100 degrees to look for lift-off (the LO of POLO) of the anterior rim of the tibial trial. A tight PCL pulls the femur posteriorly on the tibia causing impingement with the posterior lip of the curved tibial insert pushing down in back with lift-off in front. The patella should be located in the trochlear groove for this test to avoid artificial lift-off caused when an everted tight quadriceps mechanism draws the tibia anteriorly and externally. False lift-off can also occur if the surgeon has left uncapped posterior condylar bone or retained posterior osteophytes that impinge on the posterior aspect of the tibial tray. If lift-off occurs and no initial posterior tibial slope was applied, the slope can be increased to a maximum of 5 to 7 degrees.

Recession of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament

Every PCL retaining arthroplasty should probably have an initial recession of the PCL tibial attachment by either removing the entire tibial spine in front of the ligament or dissecting the PCL fibers off the retained tibial spine to the level of the bone resections.5,6 With proper measured femoral and tibial bone resection, the PCL is balanced according to the POLO test in over 90% of routine primary knees.

Release of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament

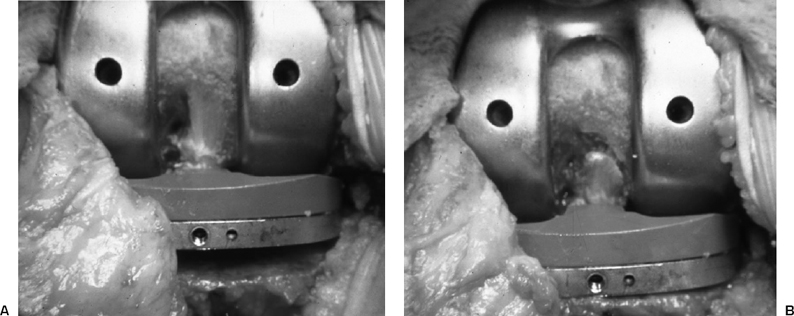

In 5 to 10% of routine knees and in a higher percentage of knees that require extensive medial-lateral ligament balancing, a formal PCL release is required to satisfy the POLO test. Some surgeons advocate further release from the tibia, but this precludes a graduated release that can be titrated accurately with the lift-off test. A femoral release of the PCL has this advantage. With the trial components in place and the knee in 90 degrees of flexion, the tight PCL fibers can be seen and palpated (Fig. 38–1A). They are usually the more lateral and more anterior fibers. The release is performed progressively until the lift-off disappears (Fig. 38–1B). In the rare case requiring complete release, the collaterals and capsule in conjunction with a curved insert will usually provide enough flexion stability so that substitution is not required. If secondary flexion laxity is created by the surgeon, PCL substitution can be considered.

Pitfalls and Pearls

- Maintain the joint line at its proper level.

- Err toward a more conservative initial distal femoral resection.

- Never leave the PCL too tight.

- Utilize the POLO test for PCL balancing.

- Recess the PCL from the tibia.

- Release the PCL from the femur.

- Increase posterior tibial slope if necessary to a maximum of 5 to 7 degrees.

- Assess and relieve posterior impingement due to retained femoral osteophytes or uncapped posterior condylar bone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree