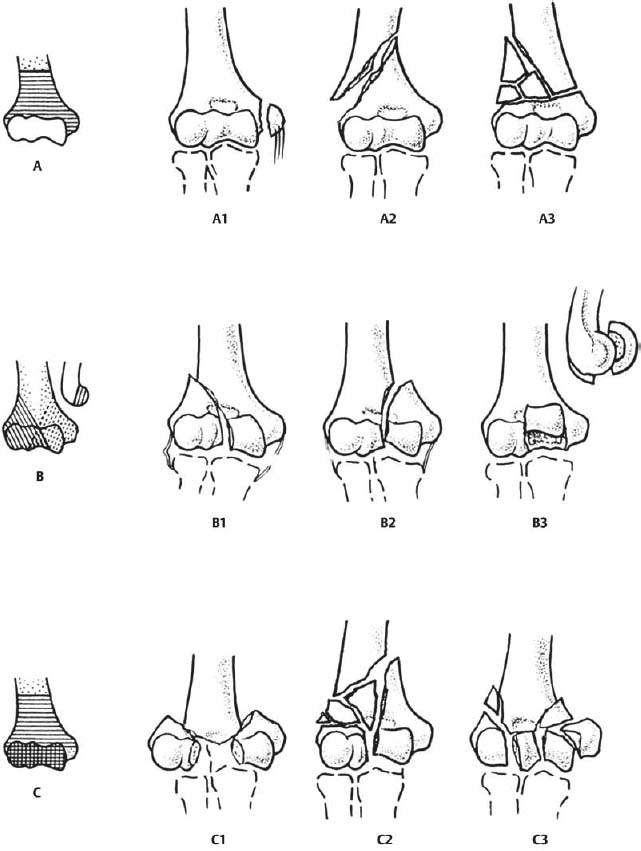

13 Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Distal Humeral Fractures As the populations of North America and Europe continue to age, the number of patients having comminuted displaced intraarticular distal humerus fractures is expected to increase. Palvanen et al1 reported an age adjusted increase in incidence of such fractures resulting from moderate trauma from 12 in 100,000 in 1970 to 28 in 100,000 in 1995. The study concluded that if this trend continued, a threefold increase in the number of distal humerus fractures would occur by 2030.1 Although fractures of the distal humerus account for only a small percentage of adult fractures (1 to 2%), traditional methods of fixation have been associated with a significant number of complications and poor outcomes.2,3 In addition, the greater the age, the worse the result of open reduction and internal fixation.4 Therefore, a difficult orthopedic problem may become increasingly common over the next 20 years. The most commonly used classification system for distal humerus fractures is the Association for the Study for Internal Fixation (ASIF).5 The principle is to divide the fracture type into three subsets based on the anatomic level of the fracture and relative involvement of the articular surface (Fig. 13–1). These fracture types are as follows: type A, completely extraarticular fracture; type B, intraarticular fracture involving only one condyle; and type C, intraarticular fracture with bicondylar disruption and loss of metaphyseal continuity with the humeral shaft. Each type can be further subdivided based on various fracture patterns and comminution.5 As with any classification system in orthopedics, this system has been used in an attempt to compare fracture patterns, the difficulties of their treatment, and the outcomes between various studies. Until the 1960s, most orthopedic surgeons believed that the preferred treatment for distal humerus fractures was nonoperative.2 This involved lengthy periods of immobilization and resulted in unacceptable outcomes. Nonoperative treatment often resulted in either a malunion with associated joint stiffness, chronic pain, and poor function, or nonunion of the fracture with a subsequent painful pseudarthrosis.3,6–8 Early attempts at open reduction and internal fixation also provided poor results. However, in the 1970s the AO group introduced instrumentation and surgical techniques that allowed accurate anatomic reduction and stable internal fixation of distal humerus fractures.9 The AO principles of anatomic reduction, rigid internal fixation, minimal soft tissue disruption, and early active range of motion (ROM) were shown to be critical in elbow fracture reconstruction.9 These principles eventually allowed early mobilization of the joint and provided for improved outcomes. Operative fixation in the elbow is a technically challenging endeavor. It requires knowledge of multiple surgical exposures, an understanding of the complex regional anatomy, and the ability to achieve fixation that allows early ROM. If adequate stability is not achieved, nonunion, malunion, posttraumatic arthritis, and stiffness of the elbow may result. The current data on internal fixation of distal humerus fractures indicate that complications such as failure of fixation, persistent pain and/or stiffness, heterotopic ossification, ulnar nerve entrapment, nonunion, malunion, and posttraumatic arthritis are common despite adhering to AO principles.6,10–12 The difficulties of anatomic reduction and internal fixation are compounded in elderly patients because of the increased comminution and osteopenia. Caja et al4 reported on a group of 22 patients with bicondylar fractures of the distal humerus treated with osteosynthesis and found that the ROM and functional outcome were most dependent on the age of the patient. They concluded that even if early mobilization was achieved the results were worse in older patients. It is not surprising that in the presence of osteopenia, internal fixation that is sufficiently stable to allow early mobilization is often the exception. Insufficient internal fixation for these fractures results in extensive immobilization and subsequent stiffness. Therefore, it is fair to conclude that the treatment of comminuted fractures of the distal humerus in elderly patients is associated with a high rate of complications and generally yields a poorer result than equivalent fractures in younger patients.2,3,7,8,13,14 Figure 13–1 The AO classification of distal humerus fractures. (From Muller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, et al. Comprehensive Classification of Fractures of Long Bones. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990. Reprinted by permission.) Jupiter and Morrey8 reviewed 846 procedures from 13 different reports on open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) for fractures of the distal humerus and found that 20% of patients had an unsatisfactory outcome. They concluded that in the elderly patients, osteopenic bone and increased comminution compounded the difficulties of achieving an anatomical reduction and stable fixation. John et al7 reported the results of surgical stabilization of 49 patients with supracondylar fractures of the humerus whose mean age was 80 years (75 to 90); 41 (84%) were intraarticular fractures, and 39 patients were evaluated at a mean follow-up of 18 months. A very good result was reported for 31% of patients, a good result for 49%, and a fair or poor result for 20%. Constant pain was reported in 5% of patients. Complications included fracture of the plate or screws in 4 patients, symptoms related to the ulnar nerve in 6, and nonunion at the site of the osteotomy of the olecranon in 2 patients. Ten patients assessed their result as fair or poor.7 Pereles et al15 performed a retrospective review of fractures of the distal humerus in 18 patients over the age of 60 years. They reported that at a minimum follow-up of 1 year, 12 patients had a good clinical outcome while 5 patients (28%) complained of moderate pain during activity for which medication was required. Helfet and Schmeling6 reviewed the results of nine published studies and reported less-than-good results in 25% of the patients. The complications included heterotopic ossification in 3 to 30% of the patients, infection in 3 to 7%, ulnar nerve palsy in 7 to 15%, failure of fixation in 5 to 15%, and nonunion in 1 to 11%.6 These reports showing a high rate of complications, residual pain, and limited function in a large percentage of patients has raised the question about the effectiveness of osteosynthesis in elderly patients and emphasized the need for better methods of treatment. It is in comparison to these outcome studies that total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) for fracture should be evaluated. The use of total hip arthroplasty in elderly patients who have a fracture of the femoral neck is well accepted. Total elbow replacement was thus suggested as an option for similarly comminuted elbow fractures in elderly patients.16 Elbow replacement has proven effective in traumatic conditions of the elbow including posttraumatic arthritis11 and in the salvage of distal humeral nonunions.10,12 As an extension of these successes, Cobb and Morrey reported their results of TEA for fractures of the distal humerus in a select patient population.16 Since then, total elbow arthroplasty has been used in cases of distal humerus fracture in the elderly. TEA has undergone numerous changes in the past 20 years. The marked improvement in the results are due to improvements in the design of the implants, the operative technique, and the selection of patients.12–14,16–25 The indications for TEA have likewise changed, and good results have been reported for carefully selected patients who have posttraumatic conditions of the elbow. Fracture classification is clearly an important factor when considering the appropriate treatment. A good rule of thumb is to expect more fracture comminution than that appreciated on preoperative radiographs. However, extensive intraarticular comminution is not the only determining factor. Extensive osteopenia and underlying inflammatory arthropathies are significant factors when considering TEA. Appropriate selection of ORIF or TEA at the time of primary treatment cannot be overstated. The decision to attempt fixation with the strategy of later converting to a TEA if the fixation fails often yields inferior results as compared with primary TEA. In a retrospective study of patients older than 65 years of age with complex elbow fractures, those who were treated with primary TEA had better results than those converted to TEA after the primary open reduction and internal fixation failed.13,18 As with any orthopedic problem, the assessment of every distal humerus fracture begins with a thorough history and physical examination. Specific details in the history should include age, handedness, mechanism of injury, prior level of function of the affected extremity, history of any inflammatory arthropathies, work demands, and associated medical comorbidities. Physical examination should include documentation of a careful baseline neurologic examination. The cervical spine, ipsilateral shoulder and wrist should be examined for associated injuries. A thorough evaluation of the skin and soft tissue around the elbow is critically important. A good soft tissue envelope is essential to being able to replace the elbow and prevent infection, stiffness, or early failure. In addition, an open fracture (particularly Gustilo types II and III) is a relative contraindication to an acute arthroplasty. However, an open fracture may benefit from arthroplasty once the soft tissue envelope has been appropriately managed. Radiographic evaluation involves orthogonal anteroposterior (AP) and lateral x-rays (Fig. 13–2). These are usually all you need for evaluating the fracture pattern and deciding on a surgical treatment plan. A computed tomography (CT) scan is occasionally ordered if a more detailed description of the intraarticular comminution is felt to be necessary. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally not needed in assessing these fractures. The physician needs to provide both patient and family with appropriate counseling about this injury and the prognosis. The presence of realistic patient expectations should be confirmed by the physician before any treatment recommendations are made. In our experience, this makes postoperative management much simpler for the patient and for the surgeon. In addition, in those patients in whom TEA is being considered, a clear understanding of the limitations imposed following surgery is necessary. Inform the patient that these prostheses do not tolerate the large mechanical stresses often associated with lifting and repetitive use of the arm and that lifelong activity restrictions will be required. Figure 13–2 (A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral radiographs of a comminuted intraarticular distal humerus fracture in a 72-year-old woman.

Classification

Outcomes of Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree