The anatomy of the spine varies from region to region. The cervical spine is light, small, and flexible; the thoracic spine is larger and relatively immobile because of its associated ribs. The lumbar spine, especially the lower part, has more mobility than the thoracic spine, but less than the cervical spine. Pathology is seen most commonly in the cervical and lumbar spines, which are the most mobile portions of the axial skeleton; they require surgery most frequently.

It is important to be able to reach the spine surgically through either an anterior or a posterior approach to treat pathology of its anterior and posterior elements. Pathologies such as vertebral body infection, fracture, and tumor often require anterior approaches. There are many anterior approaches to the spinal column; we present the basic ones that allow access to all the anterior parts of the spine.

Posterior approaches are used more often. The midline posterior approaches are the most common, permitting access to all the posterior spinal elements, as well as to the spinal cord and intervertebral discs.

Frequently, portions of the spine must be fused. Because the ilium is the best site from which to obtain bone graft material, this chapter concludes with the anterior and posterior approaches to the ilium that are used in conjunction with spinal approaches.

Posterior Approach to the Lumbar Spine

The posterior approach is the most common approach to the lumbar spine. Besides providing access to the cauda equina and the intervertebral discs, it can expose the posterior elements of the spine: the spinous processes, laminae, facet joints, and pedicles. The approach is through the midline, and it may be extended proximally and distally.

The uses of the posterior approach include the following:

Excision of herniated discs1

Exploration of nerve roots2

Spinal fusion3,4

Removal of tumors5

Position of the Patient

The posterior approach can be undertaken with the patient in either of two positions:

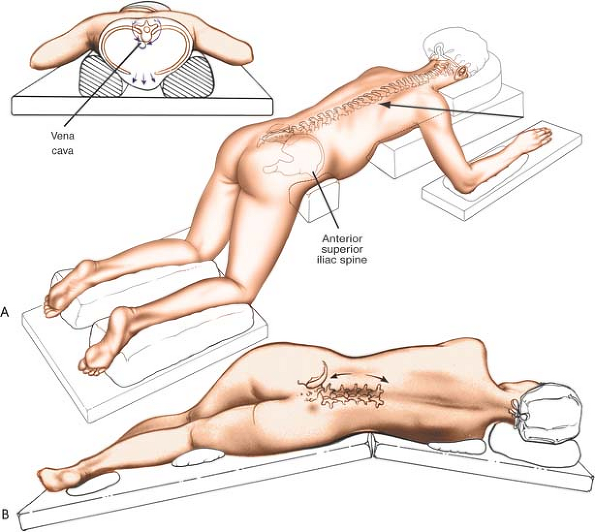

Logroll the patient into a prone position. Be sure that bolsters are placed longitudinally under the patient’s sides to allow the abdomen to be entirely free, reducing venous plexus filling around the spinal cord by permitting the venous plexus to drain directly into the inferior vena cava. The shoulders should be placed at no more than 90° of abduction and should be slightly flexed forward to relax the brachial plexus. Careful padding of the ulnar nerve at the elbow and median nerve at the wrist must be assured. Position the head and neck in a relaxed, neutral position and be sure that no pressure is applied to the eyes. The lower extremities should be padded carefully at the knees and feet. The hips are usually flexed for decompression, as it allows for an increase in interlaminar or interspinous distance and in neutral or slight extension for lumbar fusions to restore normal lordosis. The knees are flexed, and we must check that there is no pressure on the proximal fibula/common peroneal nerve region (Fig. 6-1A).

Place the patient on his or her side, with the affected side upward. Flex the patient’s hips and knees to flex the lumbar spine and open up the interspinous spaces. Make sure that the patient is positioned with the involved spinal level over the table break. Jackknifing the table can open further the intervertebral space on the upper side of the patient by putting the lumbar spine into lateral flexion. One advantage of this position is that it allows the surgeon to sit. Extravasated blood drains down, away from the operative field (see Fig. 6-1B).

For both positions, use a cold-light headlamp to illuminate the deepest layers around the spine.

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

The spinous processes are easily palpable. Note that a line drawn between the highest points on the iliac crest is in the L4-5 interspace. The line is only a rough guide, however; the best means of determining the exact level is either to insert a small needle into the spinous process and obtain a radiograph or to carry the dissection distally and identify the sacrum.

Incision

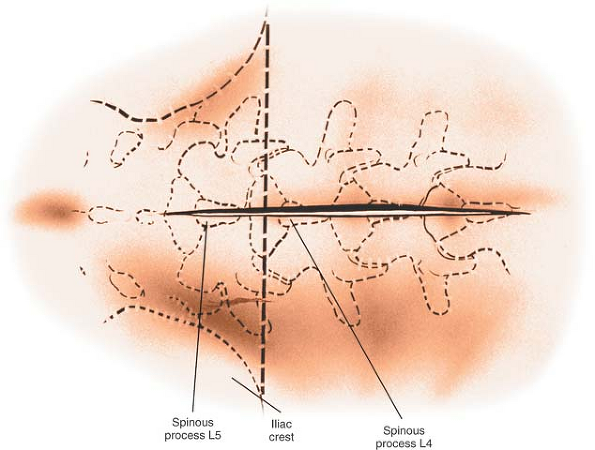

Make a midline longitudinal incision over the spinous processes, extending from the spinous process

above to the spinous process below the pathologic level. The length of the incision depends on the number of levels to be explored (Fig. 6-2).

P.259

above to the spinous process below the pathologic level. The length of the incision depends on the number of levels to be explored (Fig. 6-2).

|

Figure 6-1 (A) The position of the patient for the posterior approach to the lumbar spine. (B) Alternatively, place the patient in the lateral position with the affected side up. |

Internervous Plane

The internervous plane lies between the two paraspinal muscles (erector spinae), each of which receives a segmental nerve supply from the posterior primary rami of the lumbar nerves.

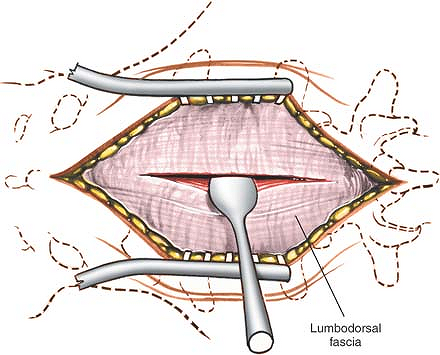

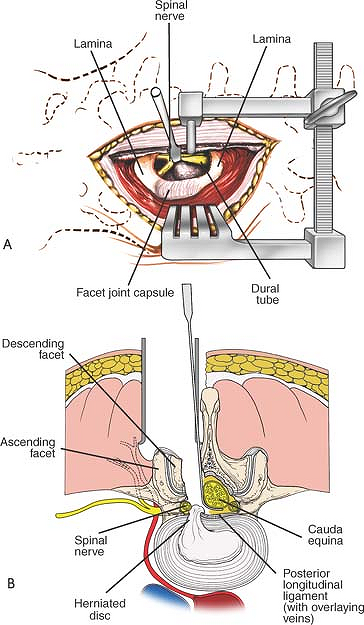

Superficial Surgical Dissection

Deepen the incision through fat and fascia in line with the skin incision until the spinous process itself is reached. Detach the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally as one unit from the bone, using a dissector, such as a Cobb elevator, or with cautery (Fig. 6-3). Dissect down the spinous process and along the lamina to the facet joint. In a young patient, the tip of the spinous process is a cartilaginous apophysis; it can be split in the midline, making subperiosteal muscle removal easier (Fig. 6-4).

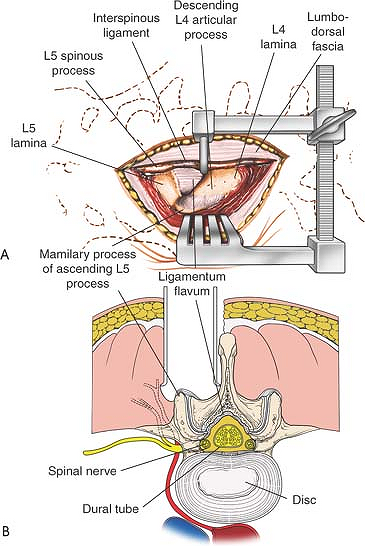

If necessary, dissection can be continued laterally, stripping the facet joint capsule from the descending and ascending facets. To do this, strip the joint capsule in a medial to lateral direction across the posterior aspect of the descending facet; then, continue over the tip of the mamillary process of the more lateral ascending facet. If the transverse processes must be reached, continue dissecting down the lateral side of the ascending facet and onto the transverse process itself (see Fig. 6-4).

Dangers

Close to the facet joints, in the area between the transverse processes, are the vessels supplying the paraspinal muscles on a segmental basis. These branches of the lumbar vessels frequently bleed as the dissection is carried out laterally. Vigorous cauterization of these

vessels may be necessary to stop the bleeding. Note that the posterior primary rami of the lumbar nerves, which also supply the paraspinal muscles segmentally, run with these vessels. Loss of some of these nerves does not totally denervate the paraspinal muscles, because they are innervated segmentally (see Fig. 6-4).

P.260

P.261

vessels may be necessary to stop the bleeding. Note that the posterior primary rami of the lumbar nerves, which also supply the paraspinal muscles segmentally, run with these vessels. Loss of some of these nerves does not totally denervate the paraspinal muscles, because they are innervated segmentally (see Fig. 6-4).

|

Figure 6-2 Make a longitudinal incision over the spinous processes, extending from the spinous process above to the spinous process below the level of pathology. A line drawn across the highest point of the iliac crest is in the L4-5 interspace. |

|

Figure 6-3 Deepen the incision through the fat and fascia in line with the skin incision until the spinous process itself is reached. Detach the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally. |

|

Figure 6-4 (A) Dissect the paraspinal muscles from the spinous process and lamina to the facet joint. Remove the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally as one unit from the bone. (B) Continue dissecting laterally, stripping the joint capsule from the descending and ascending facets. Note the branches of the lumbar vessels that bleed during stripping of the muscles. |

|

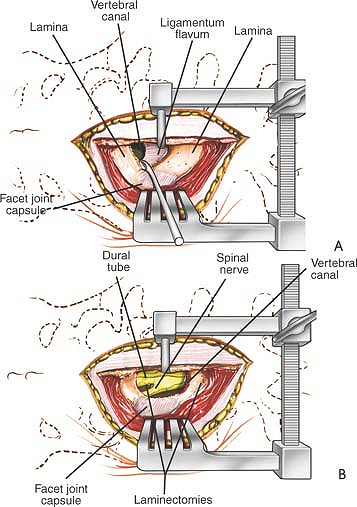

Figure 6-5 (A) Remove the ligamentum flavum by cutting its attachment to the superior or leading edge of the inferior lamina. (B) Immediately beneath the ligamentum flavum and epidural fat is the blue-white dura. Identify the nerve root. Note the overlying epidural veins. |

Deep Surgical Dissection

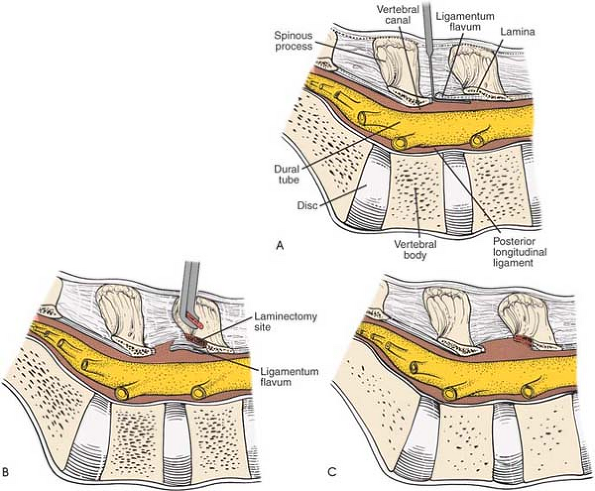

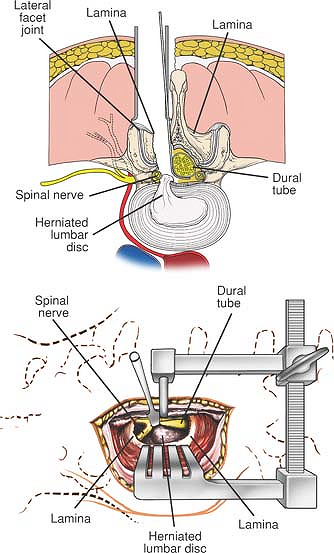

Remove the ligamentum flavum by cutting its attachments to the superior, or leading, edge of the inferior lamina using either a curette or sharp dissection. Immediately beneath are epidural fat and the blue-white dura. Using blunt dissection and staying lateral to the dura, carefully continue down to the floor of the spinal canal, retracting the dura and its nerve root medially (Figs. 6-5, 6-6, 6-7 and 6-8).

Dangers

Nerves

Each nerve root must be identified individually and protected. The more lateral the surgical field, the easier it is to identify the nerve root and retract it so the disc space can be seen. If a larger exposure is needed, incise part of the lamina on the distal portion of the involved vertebra.

Vessels

The venous plexus surrounding the nerves and the floor of the vertebra may bleed during the blunt dissection needed to reach the disc (see Fig. 6-7). The bleeding can be stopped with Gelfoam or cotton patties soaked in thrombin. Bipolar Malis cautery also may be used, although it must be done with

great care because of the proximity of the nerve roots.

P.262

great care because of the proximity of the nerve roots.

|

Figure 6-6 (A) Insert a blunt dissector under the cut edge of the ligamentum flavum. (B) Use a Kerrison rongeur to remove the distal end of the lamina. Note that the ligamentum flavum attaches halfway up the undersurface of the lamina. (C) Remove additional lamina and the remaining portion of the ligamentum flavum at its attachment to the undersurface of the lamina. |

The iliac vessels lying on the anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies may be injured if instruments pass through the anterior portion of the annulus fibrosus (see Fig. 6-21).6

How to Enlarge the Approach

Local Measures

To gain better exposure of the dura, nerve root, and disc, remove additional portions of the lamina, both from the leading edge of the lamina below and from the caudal edge of the lamina above. A portion of the facet joint itself even can be removed. Remember that it is safer to remove bone than to retract nerve roots or dura excessively. If the wound is tight, dissect the paraspinal muscles off the posterior spinal elements above and below the exposed level to make the muscles easier to retract.

To gain access to other parts of the posterior aspect of the spine, carry the dissection as far laterally as possible, onto the transverse processes. Complete lateral dissection exposes the facet joints and transverse processes, permitting facet joint fusion and transverse process fusion, if necessary (see Fig. 6-4).

Extensile Measures

To extend the approach, merely extend the skin incision proximally or distally and detach the posterior spinal musculature from the posterior spinal elements. The approach can be extended from C1 down to the sacrum.

P.263

|

Figure 6-7 (A) Using blunt dissection, carefully continue down the lateral side of the dura to the floor of the spinal canal; retract the dura and its nerve root medially. Reveal the posterior aspect of the disc. (B) Cross-section revealing the retraction of the dural tube and a herniated nucleus pulposus impinging on a nerve root. |

Minimal Access—Posterior Approach to the Lumbar Spine

Position of Patient

Place the patient in the prone position on a radiolucent table, with the abdomen free and the extremities padded.

Landmarks and Incision

Palpate the spinous processes to identify the midline. Fluoroscopy is used to determined the disc level.

Internervous Plane

The approach splits the fibers of the erector spinae muscle group that are innervated segmentally.

Superficial Surgical Dissection

The skin, subcutaneous adipose tissue, and the erector spinae fascia are sharply divided with a knife.

Deep Surgical Dissection

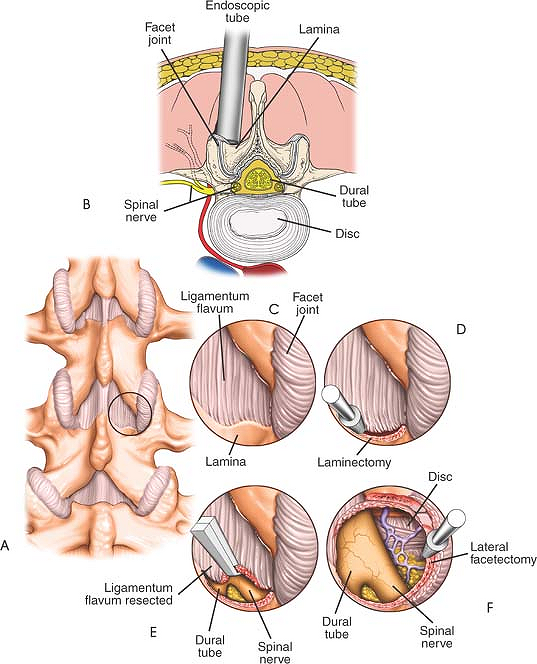

The erector spinae muscle fibers are split by the dilating/retracting tube and abutted against the lamina and medial facet joint.7 The distal lamina and ligamentum flavum are resected on the affected side to expose the nerve root over the disc. Some of the medial facet can be resected to decompress the lateral recess. The nerve root is then retracted medially to expose the pathologic disc (Fig. 6-9).

P.264

|

Figure 6-8 With the use of a microscope and retractor, a 3-cm incision can be used to expose the disc at a single level. |

Dangers

Meticulous positioning of the retractors must be done with landmarks and fluoroscopy because a very small incision is made. Any deviation from the planned course may make it difficult to find the pathology. If the incision is too medial, the spinous processes may impede the proper positioning of the retracting tube. A tube that is angled excessively will make it difficult to work and target the microscope. This can be mitigated by using a tilting operating table. Meticulous hemostasis is important, as the small access port can be obscured easily by excessive bleeding.

How to Enlarge the Approach

The tube/retractor can be repositioned or angled differently to address pathologies in different locations, for example, to access a sequestered disc, a far lateral disc, or to decompress a contralateral spinal stenosis. Larger tubes are available if more exposure is required. In the lordotic spine, a small change in the angle of the tube can permit access to an adjacent level.

P.265

|

Figure 6-9 (A) Localization of the level is performed with fluoroscopy. The starting point is 2 cm from the midline directly above the involved disc. (B) A 1- to 2-cm incision is made longitudinally. The fascia is incised. The erector muscles are split bluntly with dilating tubes. The retracting tube is positioned at the intersecting point of the lamina above the facet laterally and the ligamentum flavum medially and distally. (C) The proximal and distal lamina are thinned with a high speed burr. (D) The ligamentum flavum can be retracted medially or simply resected with a Kerrison rongeur is used to resect the caudad aspect of the lamina. (E) The ligamentum flavum can be retracted medially or simply resected with a Kerrison rongeur, exposing the dura. (F) The nerve root is exposed with the affected disc directly ventral to it. |

P.266

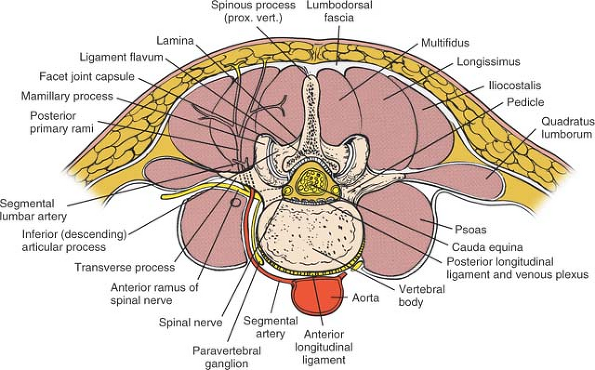

Applied Surgical Anatomy of the Posterior Approach to the Lumbar Spine

Overview

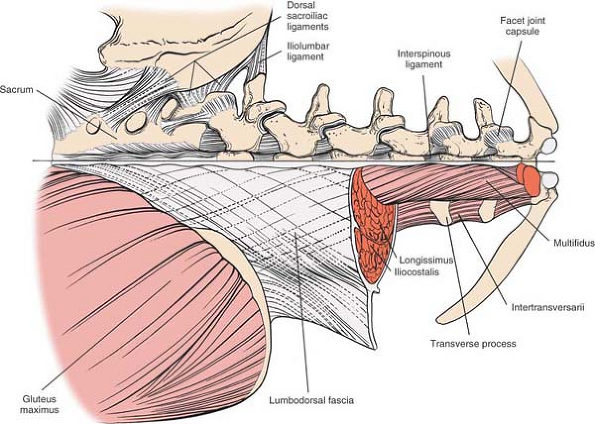

The muscles of the lumbar spine are made up of superficial and deep layers. The superficial layer consists of the latissimus dorsi, a powerful muscle of the posterior axillary wall that originates from the spinous processes and inserts into the intertubercular groove of the humerus. The surgically important deep layer consists of the paraspinal muscles and itself is divided into two layers: the superficial portion, which contains the sacrospinalis muscles (erector spinae), and the deep portion, which consists of the multifidus and rotator muscles (Fig. 6-10).

|

Figure 6-10 An overview of the musculature of the lumbosacral spine. In the lumbar spine, the sacrospinalis system is composed of the multifidi, longissimus, and iliocostalis muscles. Note the intertransversarii muscles located deeper. Note the dorsal sacroiliac ligaments. |

This arrangement is not apparent during surgery, because the approach involves detaching all these muscles in a single mass.

P.267

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

Spinous Processes. The spinous processes in the lumbar area are thick. The distal end of the tip of the spinous process is bulbous and extends slightly caudally. Each process separates the paraspinal muscles on each side. In a growing patient, the processes are capped by cartilaginous apophyses, which, when split, make it easier to remove the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally.

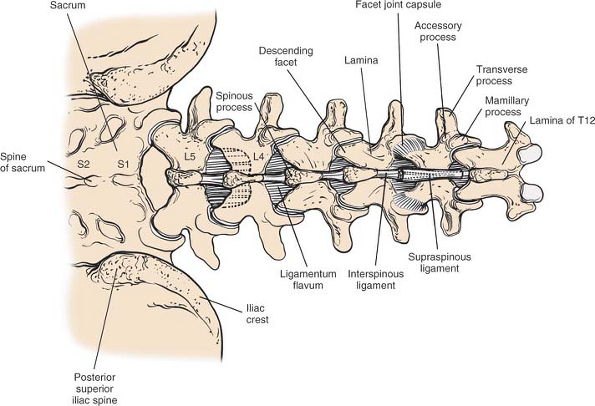

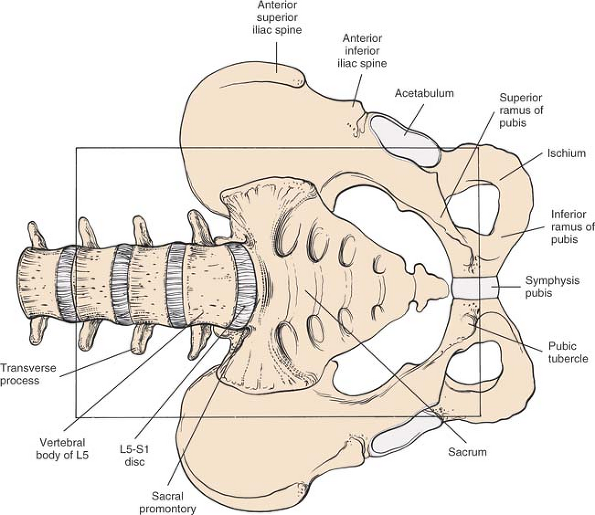

Posterior Superior Iliac Spine and Crest of the Ilium. The broad iliac crests run posteriorly at a 45° angle toward the midline. Because muscles either take origin from or insert into the crest (none cross it), it has a palpable subcutaneous border. The palpable, visible dimples over the buttocks lie directly over the posterior superior iliac spines. A line drawn between the two posterior superior iliac spines crosses the second part of the sacrum; a line drawn between the highest points of the iliac crest crosses between the spinous processes of L4 and L5 (Fig. 6-11).

|

Figure 6-11 The bony anatomy of the lumbosacral spine and the posterosuperior aspect of the pelvis. The facet joint capsules, ligamentum flavum, and interspinous ligaments are shown. A line drawn across the crest of the ilium intersects the L4-5 interspinous space. A line crossing the posterior superior iliac spine intersects the second part of the sacrum. |

Incision

The midline incision follows the course of the spinous processes. It tends to heal with a fine, thin scar, because it is not under tension after suturing and is attached firmly to underlying fascia. No major cutaneous nerves cross the midline.

Superficial Surgical Dissection and Its Dangers

The dorsal lumbar fascia and the supraspinous (supraspinal) ligaments lie between the skin and the

spinous processes. The fascia is a broad, relatively thick, white sheet of tissue that forms a sheath for the sacrospinalis muscles and attaches to the spinous processes (see Fig. 6-10). It extends to the cervical spine, where it becomes continuous with the nuchal fascia of the neck. Medially, it is attached to the spinous processes of the vertebrae, the supraspinous ligaments, and the medial crest of the sacrum. Inferiorly, it is attached to the iliac crests. Laterally, it is continuous with the origin of the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis and latissimus dorsi muscles.

P.268

spinous processes. The fascia is a broad, relatively thick, white sheet of tissue that forms a sheath for the sacrospinalis muscles and attaches to the spinous processes (see Fig. 6-10). It extends to the cervical spine, where it becomes continuous with the nuchal fascia of the neck. Medially, it is attached to the spinous processes of the vertebrae, the supraspinous ligaments, and the medial crest of the sacrum. Inferiorly, it is attached to the iliac crests. Laterally, it is continuous with the origin of the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis and latissimus dorsi muscles.

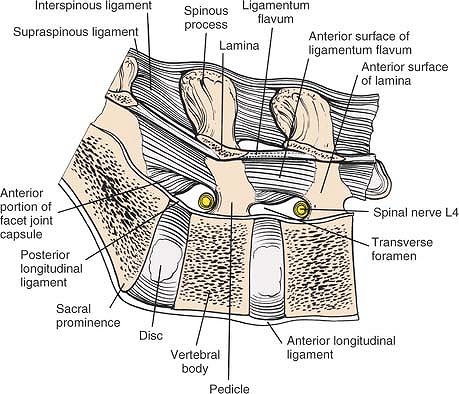

The supraspinous ligaments extend from vertebra to vertebra, connecting the spinous processes. They blend intimately with the attachment of the dorsal lumbar fascia to the spinous processes (Fig. 6-14).

Further dissection consists of detaching the two layers of muscle from bone. Because these muscles are detached in a single mass, their critical feature, in regard to their surgical anatomy, lies in their blood supply and not in their structure. The segmental lumbar vessels branch directly from the aorta. They wrap around the waist of each vertebral body and then ascend close to the pedicle, where they divide into two branches. One supplies the spinal cord; the other, larger branch then comes directly posteriorly to supply the paraspinal musculature. During the approach, these vessels appear between the transverse processes, close to the facet joints (see Fig. 6-11). They often bleed as dissection is carried out. In addition, the arteries branch within the muscle bodies, frequently creating a very vascular field. For this reason, the dissection should be kept as close to the midline as possible; no major vessels cross the midline, and the plane is safe for use (Fig. 6-13; see Fig. 6-11).

|

Figure 6-12 A sagittal section through the lamina of a lumbar vertebra. Note the origin and insertion of the ligamentum flavum as well as the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments. The nerve roots exit at the inferior aspect of the pedicle. |

Deep Surgical Dissection and Its Dangers

The ligamentum flavum is the most important structure in the deep layer. Consisting of yellow elastic tissue, the ligament takes origin from the leading edge of the lower lamina and inserts into the anterior surface of the lamina above, about halfway up onto a small ridge (Fig. 6-12). The two ligamenta flava, one from each side, meet in the midline, but generally do not fuse; the plane between the ligamentum flavum and the underlying dura fat can be entered most easily at that point. Because of its attachments, the ligamentum flavum is removed best from the leading edge of the lower lamina through sharp dissection or curettage (see Fig. 6-5A).

The major danger in the deep dissection involves damage to the dura. Once the ligamentum flavum is entered, a thin spatula should be placed beneath it to protect the underlying dura from being torn (see Fig. 6-6A). The cord itself and the nerve roots often are difficult to see as a result of bleeding from epidural veins. The veins, which are thin-walled and easy to rupture, even with blunt dissection, can be controlled by direct pressure using a pattie or by bipolar cautery.

P.269

|

Figure 6-13 Cross-section at the L3-4 disc space, looking distally. The segmental lumbar vessels branch directly from the aorta. They wrap around the waist of each individual vertebral body and then ascend close to the pedicle, where they divide into two branches. One branch supplies the cord; the other, larger branch proceeds directly posterior to supply the paraspinal musculature. During the surgical approach, these vessels appear between the transverse processes, close to the facet joints. Note that the posterior primary rami and the posterior branches of the lumbar vessels appear between the transverse processes close to the pedicle and descending facet. |

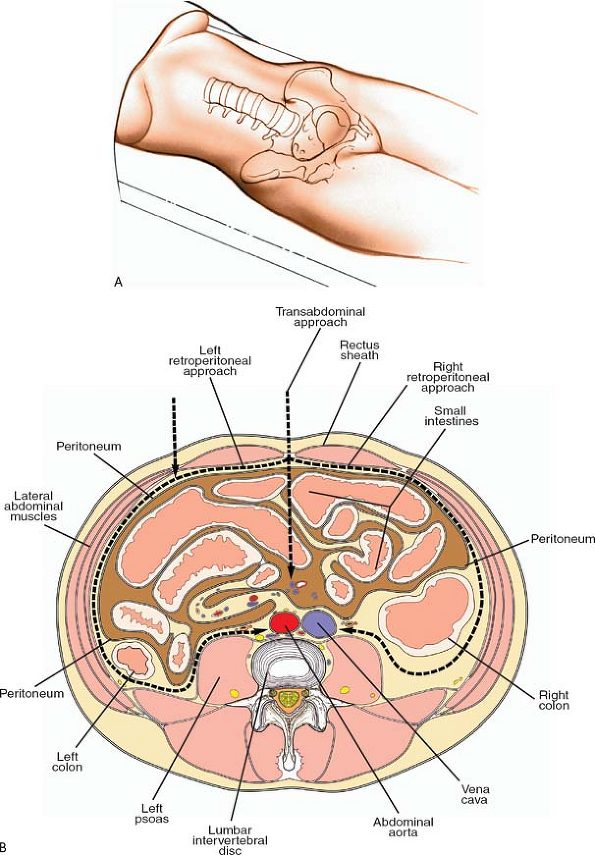

Anterior (Transperitoneal and Retroperitoneal) Approach to the Lumbar Spine

The transperitoneal anterior approach to the lumbar spine usually is reserved for fusing L5 to S1. It also may be used for fusing L4 to L5, although it then involves mobilization of the great vessels. Although the approach is simple in concept, the occasional user may appreciate the assistance of a general surgeon who is more familiar with the area exposed.8,9

Position of the Patient

Place the patient supine on the operating table (see Fig. 6-14). Make sure that two areas remain bare for incision: one for the abdominal incision, and one for harvesting an anterior iliac crest bone graft. Insert a urinary catheter to keep the bladder empty. Use of mechanical calf compression is recommended to decrease the risk of thromboembolism.

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

The umbilicus normally is opposite the L3-4 disc space, but varies in level depending on how heavy the patient is.

P.270

|

Figure 6-14 With the patient in the supine position (A), the anterior lumbar spine can be approached by a transperitoneal, left retroperitoneal, or right retroperitoneal path (B). |

P.271

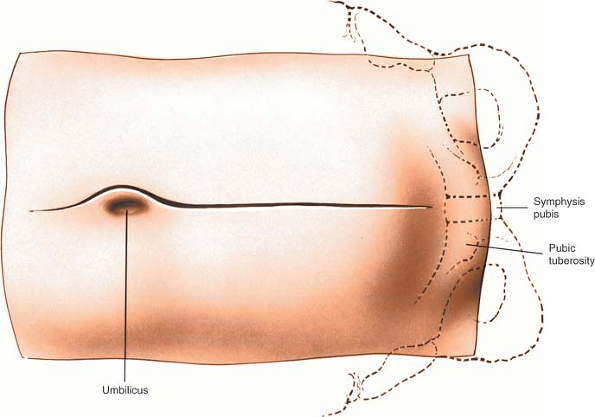

Palpate the pubic symphysis at the lower end of the abdomen through the fatty mons pubis. The pubic tubercle, on the upper border of the pubis just lateral to the midline, may be easier to palpate than the superior surface of the symphysis itself.

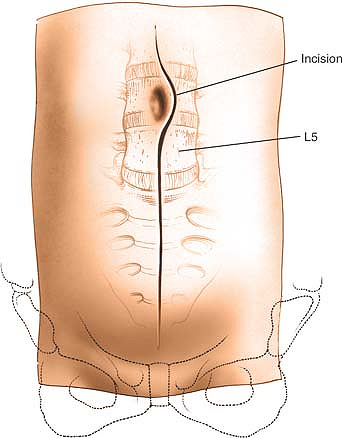

Incision

Make a longitudinal midline incision from just below the umbilicus to just above the pubic symphysis. Extend it superiorly, curving it just to the left of the umbilicus and ending about 2 to 3 cm above it. Heavier patients will require longer incisions (Fig. 6-15).

Internervous Plane

The midline plane lies between the abdominal muscles on each side, segmentally supplied by branches from the seventh to the 12th intercostal nerves. Therefore, this incision can be extended from the xiphisternum to the pubic symphysis.

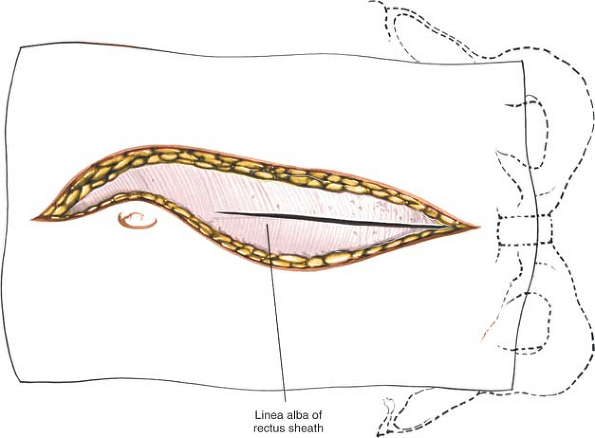

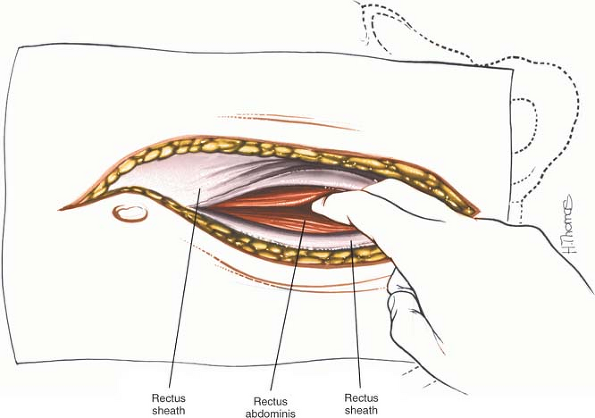

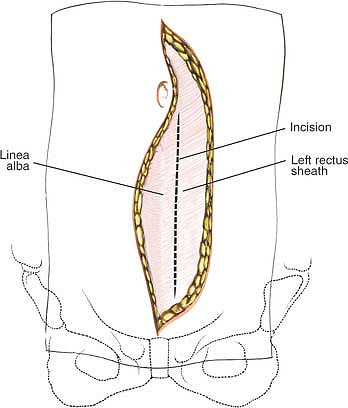

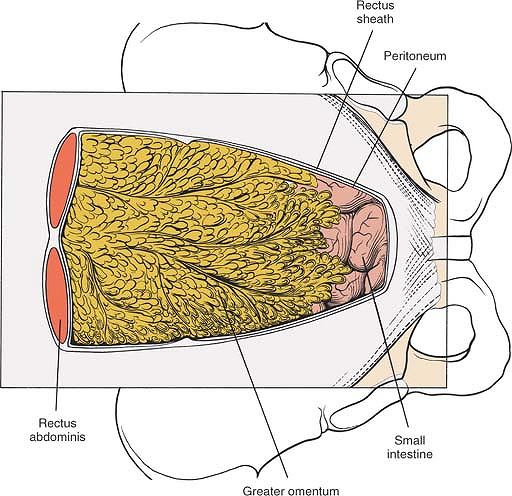

Superficial Surgical Dissection

Deepen the wound in line with the skin incision by cutting through the fat to reach the fibrous rectus sheath. Incise the sheath longitudinally, beginning in the lower half of the incision, to reveal the two rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 6-16). Separate the muscles with the fingers to expose the peritoneum (Fig. 6-17). Then, pick up the peritoneum carefully between two pairs of forceps and, after making sure that no viscera are trapped beneath it, incise it with a scissors (Fig. 6-18). Extend the incision distally, but take care not to incise the dome of the bladder at the inferior end of the wound. With one hand inside the abdominal cavity to protect the viscera, carefully deepen the upper half of the incision, staying in the midline and cutting through the linea alba, the band of fibrous tissue that separates the two rectus abdominis muscles in the upper half of the abdomen. Complete the exposure by cutting through the peritoneum in the upper half of the wound (Fig. 6-19).

|

Figure 6-15 Make a longitudinal midline incision from just below the umbilicus to just above the pubic symphysis. Extend it superiorly, to the left of the umbilicus. |

Deep Surgical Dissection

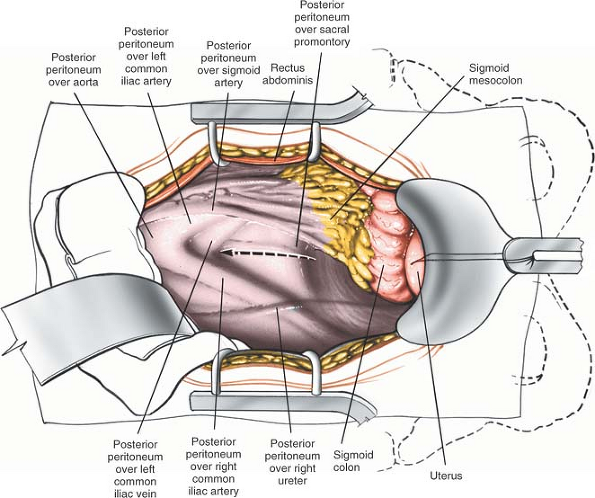

Use a self-retaining Balfour retractor to retract the rectus abdominis muscles laterally and the bladder distally (Fig. 6-20). Perform a routine abdominal exploration. Next, put the operating table in Trendelenburg’s position at 30° and carefully pack the bowel

in a cephalad position, keeping it inside the abdominal cavity. Spread a moist lap pad (swab) over it to prevent loops of bowel from slipping free. It is much safer to keep the bowel within the abdominal cavity, but do not pack it so tightly that vascular compromise is induced. In women, the uterus may be retracted forward with a 0 silk suture placed in its fundus and tied to the Balfour retractor.

P.272

in a cephalad position, keeping it inside the abdominal cavity. Spread a moist lap pad (swab) over it to prevent loops of bowel from slipping free. It is much safer to keep the bowel within the abdominal cavity, but do not pack it so tightly that vascular compromise is induced. In women, the uterus may be retracted forward with a 0 silk suture placed in its fundus and tied to the Balfour retractor.

|

Figure 6-16 Deepen the wound in line with the skin incision by cutting through the fat to reach the fibrous rectus sheath. Incise the sheath longitudinally. |

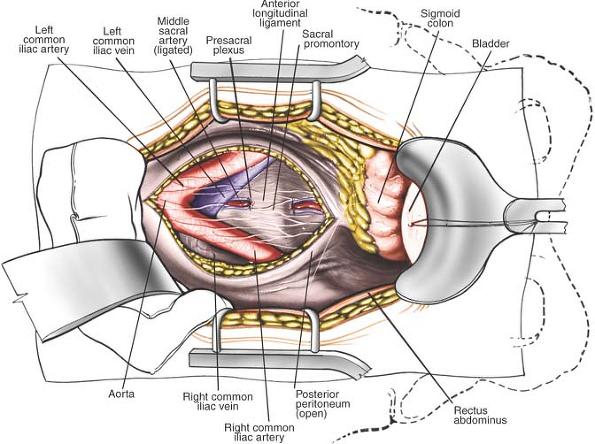

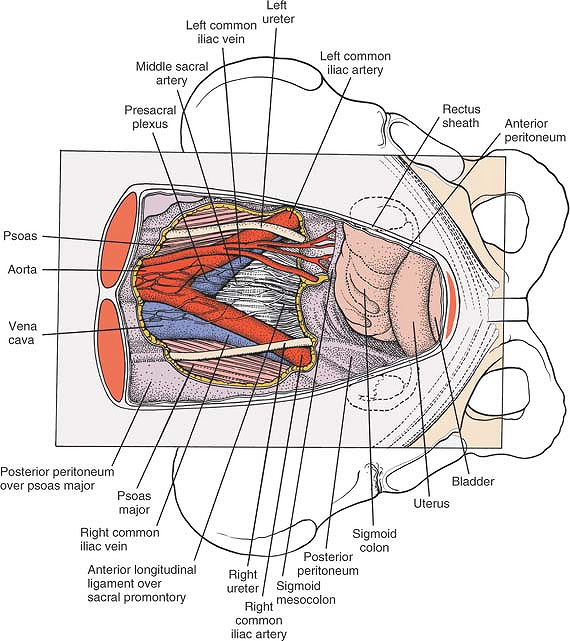

Infiltrate the tissue over the anterior surface of the sacral promontory with a few milliliters of saline solution to make dissection easier and to allow identification of the presacral parasympathetic nerves that run down through this area. For the L5-S1 disc space, incise the posterior peritoneum in the midline over the sacral promontory. The sacral artery runs down along the anterior surface of the sacrum and must be ligated or clipped. The ureters should be well lateral to the surgical approach.

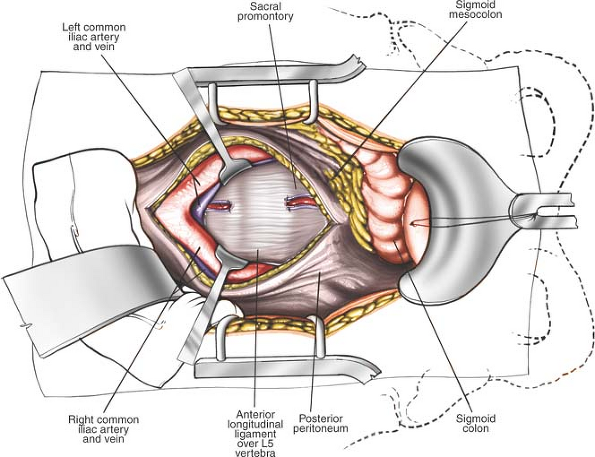

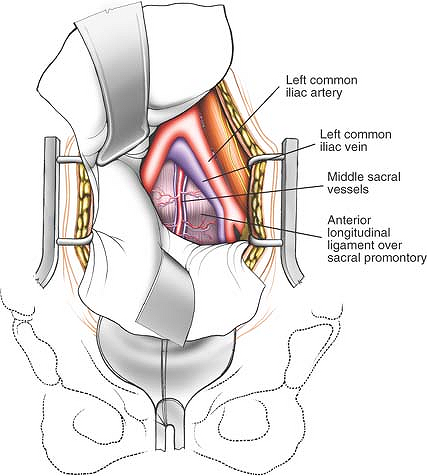

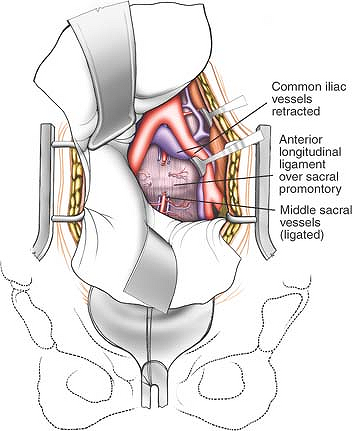

Preserve any small nerve fibers that are found. Identify the L5-S1 disc space either by palpating its sharp angle or by inserting a metallic marker and taking a radiograph. The L5-S1 disc space lies below the bifurcation of the aorta; it should be possible to expose it fully without mobilizing any of the great vessels (Figs. 6-21 and 6-22).

Operating on the L4-5 disc space requires a larger exposure; mobilizing the great vessels is necessary, unless the vascular bifurcation occurs much higher. Carefully incise the peritoneum at the base of the sigmoid colon and mobilize the colon upward and to the right to expose the bifurcation of the aorta, the left common iliac artery and vein, and the left ureter. Identify the aorta just above its bifurcation and gently begin blunt dissection on its left side. Identify and ligate the fourth and fifth left lumbar vessels, then divide them. Now, the aorta, vena cava, and left common iliac vessels can be moved to the right, exposing the L4-5 disc space. This exposure is difficult to achieve; a high incidence of venous thrombosis has been reported with anterior surgery at this level. Take care not to injure the left ureter, which crosses the left common iliac vessels roughly over the sacroiliac joint. The ureter may have to be moved laterally, but mobilize it only as much as necessary to reduce the risk of postoperative ischemic stricture formation.

An alternative method is to approach the L4-5 disc space from below, working upward into the apex of the vascular bifurcation. Isolate the left and right common iliac artery, placing umbilicus loops around them. Retract the two arteries cephalad and laterally

to expose the common iliac veins. Dissect into the confluence of the veins and isolate the left common iliac vein with a loop. Gently retract the venous structures to expose the disc space. Use only minimal retraction to avoid injuring the intima, which may lead to venous thrombosis (see Fig. 6-22).

P.273

P.274

to expose the common iliac veins. Dissect into the confluence of the veins and isolate the left common iliac vein with a loop. Gently retract the venous structures to expose the disc space. Use only minimal retraction to avoid injuring the intima, which may lead to venous thrombosis (see Fig. 6-22).

|

Figure 6-17 With your fingers, separate the rectus abdominis muscles in the midline to expose the peritoneum. |

|

Figure 6-18 Pick up the peritoneum with forceps and incise it. |

|

Figure 6-19 With one hand inside the abdominal cavity to protect the viscera, carefully deepen the upper half of the incision, staying in the midline and cutting through the linea alba. |

P.275

|

Figure 6-20 Use a self-retaining retractor to retract the rectus abdominis muscles laterally and the bladder distally. Carefully mobilize and retract the bowel in a cephalad position, keeping it inside the abdominal cavity. Observe the posterior peritoneum overlying the bifurcation of the great vessels and the promontory of the sacrum. Incise the peritoneum longitudinally. |

Dangers

Nerves

The presacral plexus is critically important to sexual function. Injury to the plexus at L5-S1 may cause retrograde ejaculation and injury more distal on the sacrum or deep in the pelvis may cause importance. Therefore, dissection should be carried out carefully, and only with a blunt peanut dissector. The incision over the anterior part of the sacrum should be made in the midline, and it should be long enough to allow for lateral mobilization of these nerves with minimal trauma. Injecting saline solution into the presacral tissue aids in identifying and preserving these nerves (see Figs. 6-21 and 6-34).10,11,12

Arteries and Veins

The middle sacral artery can be a troublesome bleeder in the region of the L5-S1 disc space and must be tied off (see Fig. 6-21).

The aorta and inferior vena cava are tethered to the anterior surface of the lumbar vertebrae by the lumbar vessels. These smaller vessels must be ligated and cut to allow the great vessels to be lifted forward off the lumbar vertebrae, exposing the L4-5 disc space (see Fig. 6-13). It is important to dissect these vessels out carefully without cutting them flush with the aorta.

If the vessels are cut flush, there will be, in effect, a hole in the aorta, and the bleeding may be extremely difficult to control. Mobilization of the venous structures should be undertaken very carefully, because they are fairly fragile and easily traumatized. Damage to these vessels may result in thrombosis; mobilization and retraction should be kept to a minimum.

P.276

If the vessels are cut flush, there will be, in effect, a hole in the aorta, and the bleeding may be extremely difficult to control. Mobilization of the venous structures should be undertaken very carefully, because they are fairly fragile and easily traumatized. Damage to these vessels may result in thrombosis; mobilization and retraction should be kept to a minimum.

|

Figure 6-21 Retract the posterior peritoneum to reveal the bifurcation of the aorta and vena cava. Ligate the middle sacral artery. Identify the presacral parasympathetic plexus overlying the aorta and the sacral promontory. |

Special Structures

The ureter must be mobilized laterally, particularly for exposure of the L4-5 disc space. It can be identified easily by gently pinching it with a pair of non-toothed forceps to induce peristalsis (see Fig. 6-34).

How to Enlarge the Approach

Local Measures

Packing the bowel away carefully is the key to adequate exposure in the pelvis. Careful mobilization of the great vessels is crucial to exposure higher up (see Figs. 6-20 and 6-22).

Extensile Measures

In theory, this exposure can be extended to the xiphisternum, but the exposure of higher discs almost always is performed better through a retroperitoneal approach.

P.277

|

Figure 6-22 Mobilize the great vessels as needed for additional exposure. Expose the L5-S1 disc space subperiosteally. |

Anterior Retroperitoneal Approach to the Lumbar Spine

Position of the Patient

Position the patient lying flat and supine on a radiolucent table.

Landmarks and Incisions

The landmark for access to the L5-S1 disc is usually distal to the midway mark between the umbilicus and symphysis. A more distal incision is required for the L5-S1 disc because of its downward orientation. The L4-5 disc is generally located a few centimeters from the umbilicus, and the incision is made directly over the disc. L3-4 is a few centimeters proximal to the umbilicus and is also approached with an incision directly over it. The incisions can be transverse if only one level is done or the more versatile incision for one or more level is a midline longitudinal or slight oblique incision (Fig. 6-23).13

Internervous Plane

An interval just medial to the rectus abdominus and under the rectus is developed. The rectus is innervated segmentally.

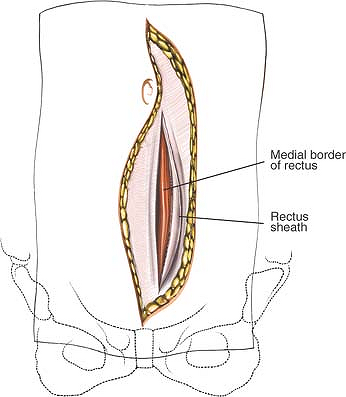

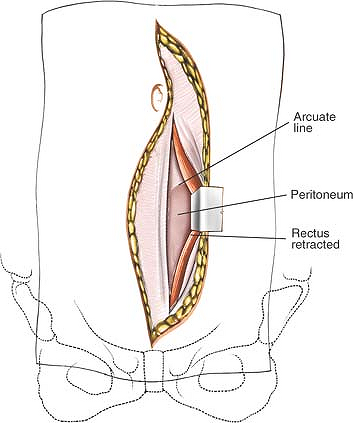

Superficial Surgical Dissection

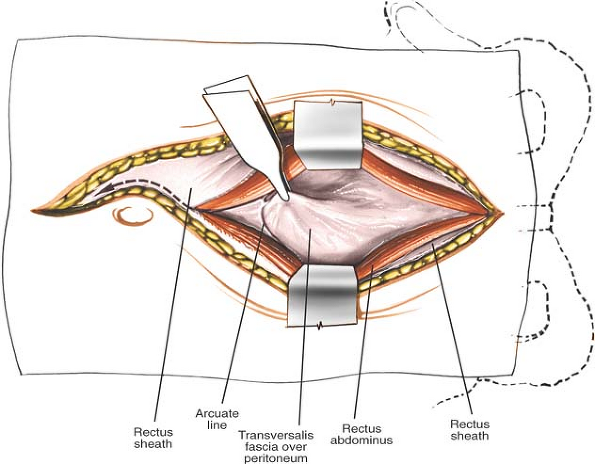

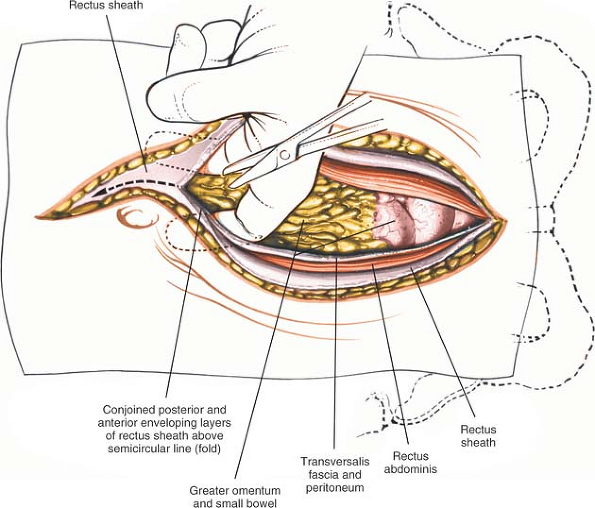

Continue the incision to the ventral rectus fascia (Fig. 6-24). The rectus fascia is cut longitudinally on the medial edge of the muscle (Fig. 6-25). The medial edge is identified, and the rectus is lifted up and retracted to expose the dorsal fascia and the arcuate line (Fig. 6-26). The inferior epigastric vessels are identified and preserved. Blunt dissection is used to develop a plane dorsal to the rectus abdominis and toward the lower quadrant. If exposing proximal to L5, the fascia of the arcuate line is divided (Fig. 6-27).

P.278

|

Figure 6-23 The landmarks for an anterior minimal access retroperitoneal approach are shown. The final localization should be done radiographically prior to the incision as the disc level may vary. The incisions can be transverse, longitudinal, or slightly oblique. The incisions for L3-4 and L4-5 are generally performed directly over the disc level, whereas the L5-S1 disc must be approached through a more distal incision given the downward orientation of the disc. |

Deep Surgical Dissection

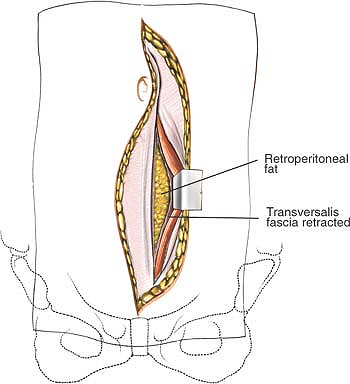

Continuing the blunt dissection toward the left lower quadrant, retroperitoneal fat is eventually encountered; underneath it, the psoas muscle can be seen. At this point, branches of the genitofemoral nerve are readily identified lying on the psoas and just medial is the common iliac artery. Retractors appropriate to the direction of the incision and size should be determined (Fig. 6-28). The ureter is generally seen on the underside of the peritoneum. The peritoneum and ureter are retracted medially and the common iliac vein is seen just dorsal to the artery and crossing from proximal-lateral to distal-medial. Caution must be used not to damage the thin walls of the vein, as it is easily the most fragile structure of this approach. The soft tissues in front of the L5-S1 disc and sacral promontory are bluntly pushed medially to expose the middle sacral vein(s) (Fig. 6-29). The veins require clipping, cauterizing, and ligating to divide them and mobilize the left iliac vein. To expose the L4-5 disc, the dissection is moved proximal to the iliac vessels. A plane between

the psoas and the iliac vessels is developed bluntly. The ascending iliolumbar vein should be identified and ligated/clipped before retracting the iliac vein.14

P.279

P.280

the psoas and the iliac vessels is developed bluntly. The ascending iliolumbar vein should be identified and ligated/clipped before retracting the iliac vein.14

|

Figure 6-24 The incision is continued to the ventral fascia of the rectus abdominus. The midline can be identified by the crisscrossing fibers of the fascia. |

|

Figure 6-25 The rectus fascia is cut longitudinally on the medial edge of the muscle. |

|

Figure 6-26 The medial edge is identified and the rectus is lifted up and retracted to expose the dorsal fascia and the arcuate line. |

|

Figure 6-27 The epigastric vessels are identified and preserved. Blunt dissection is used to develop a plane dorsal to the rectus abdominis and toward the lower quadrant. If exposing proximal to L5, the fascia of the arcuate line is divided. |

|

Figure 6-28 Continuing the blunt dissection toward the left lower quadrant, retroperitoneal fat is eventually encountered; underneath it, the psoas muscle can be seen. At this point, branches of the genitofemoral nerve are readily identified lying on the psoas and just medial is the common iliac artery. |

Dangers

Nerves

The presacral plexus of nerves is critically important to sexual function. Dissection should be gentle and blunt with all the soft tissues anterior to the disc moved as a unit with the retroperitoneum. Bipolar cautery should be used selectively.

The sympathetic chain can be found medial and deep to the psoas on the lateral vertebral body particularly when exposing proximal to L5.

Arteries and Veins

The middle sacral artery can be a troublesome bleeder in the region of the L5-S1 disc space and must be tied off (see Fig. 6-21).

The aorta and inferior vena cava are tethered to the anterior surface of the lumbar vertebrae by the lumbar vessels. These smaller vessels must be ligated and cut to allow the great vessels to be lifted forward off the lumbar vertebrae, exposing the L4-5 disc space (see Fig. 6-13). It is important to dissect these vessels carefully, without cutting them flush with the aorta. If the vessels are cut flush, there will be, in effect, a hole in the aorta, and the bleeding may be extremely difficult to control. Mobilization of the venous structures should be undertaken very carefully, because they are fairly fragile and easily traumatized. Damage to these vessels may result in thrombosis; mobilization and retraction should be kept to a minimum.

|

Figure 6-29 The soft tissues in front of the L5-S1 disc and sacral promontory are bluntly pushed medially to expose the middle sacral vein(s). |

Special Structures

The ureter can be mobilized lateral or medial with the retroperitoneal approach. It is generally easier to let the ureter be moved medially with the rest of the retroperitoneum. It can be identified by inducing peristalsis by gently pinching it with a pair of nontoothed forceps.

How to Enlarge the Approach

The retroperitoneal approach can expose from the distal aspect of T11 to S1. Exposing more proximal discs requires control and division of the segmental vessels to mobilize the aorta and vena cava.

P.281

Applied Surgical Anatomy of the Anterior Approach to the Lumbar Spine

Overview

The anterior approach to the lumbar spine involves three stages of dissection. The superficial stage consists of cutting the skin and subcutaneous tissues down to the bowel. Below the skin lies the linea alba, a fibrous structure in the midline that is identified most easily in the upper abdomen. Cutting the linea alba in the lower half of the abdomen exposes the rectus muscle, which can be separated by finger pressure. Beneath it is the posterior rectus sheath and peritoneum.

The anatomy of the intermediate stage, which involves packing away the bowel, is the anatomy of the bowel and is not included in this book.

The deep stage of dissection consists of mobilizing the retroperitoneal structures that lie anterior to the L4-5 and L5-S1 disc spaces. These structures include the aorta, vena cava, common iliac vessels, lumbar vessels, ureter, and presacral plexus.

|

Figure 6-30 Superficial aspect of the distal rectus sheath. Note that the fibers of the external oblique appear laterally. |

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

The umbilicus lies superficial to the linea alba. It usually is about halfway between the pubic symphysis and the infrasternal notch, although it may be pulled lower in obese patients.

The linea alba is marked externally by a groove in the midline of the abdomen. It divides one side of the rectus abdominis muscle from the other. In the upper abdomen, it actually separates the two muscles; cutting through it leads directly down to the peritoneum, with neither muscle being exposed. Below the umbilicus, the linea alba is less distinct; it does not separate the two rectus muscles.

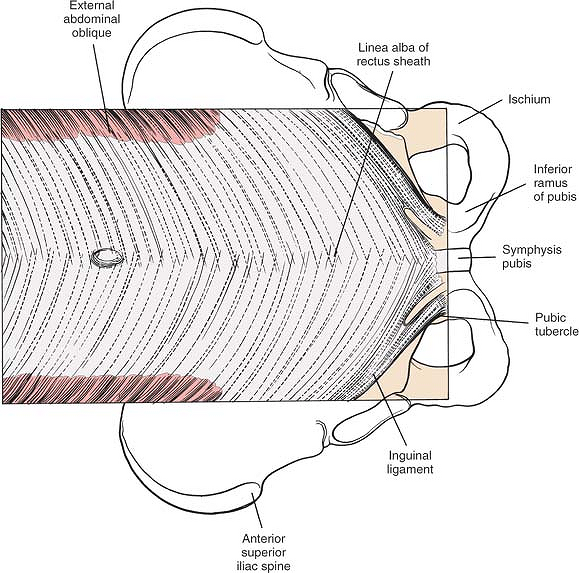

The pubic symphysis is the articulation between the two pubic bones in the midline of the body. It is a relatively immobile joint (diarthrodial; Fig. 6-30).

P.282

Incision

The midline longitudinal incision arches around the umbilicus. Because the skin is mobile and loosely attached to the tissues immediately beneath it, it heals with a thin scar. The cleavage or tension lines below the umbilicus appear in a chevron pattern, with the apex of the V in the midline.

The skin of the anterior abdominal wall is supplied segmentally from T7 in the region of the xiphoid to T12 just above the inguinal ligament. These segmental nerves do not cross the midline. Therefore, midline incisions do not cut any major cutaneous nerves.

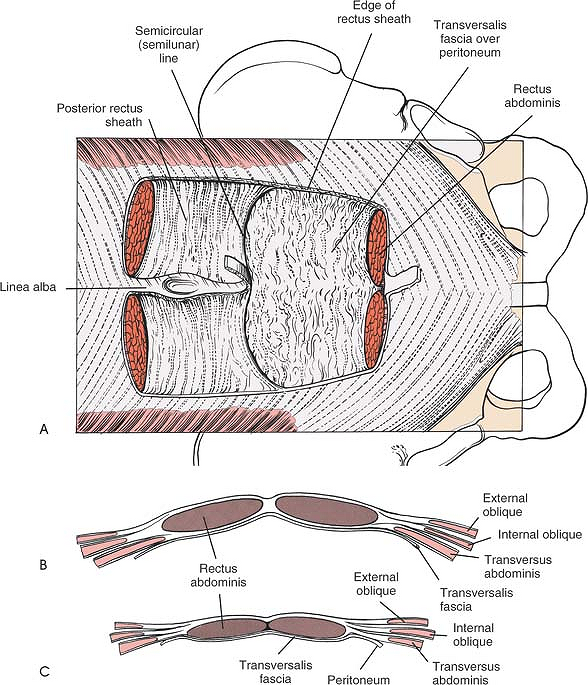

Superficial Surgical Dissection and Its Dangers

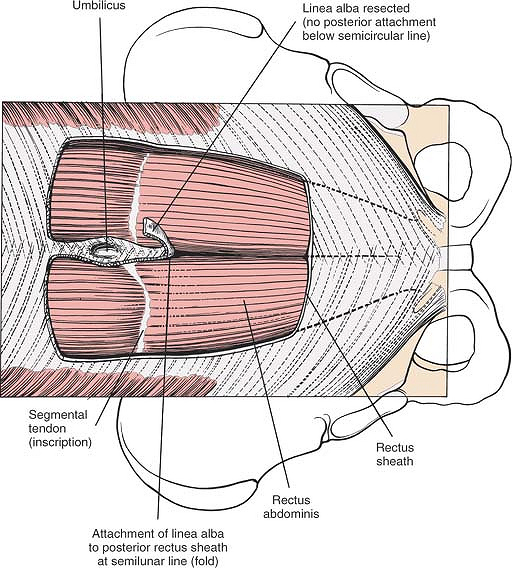

The long, flat rectus abdominis muscle extends along the length of the entire abdomen, split into two muscles in the upper half by the linea alba. The muscle is enclosed in a fascial sheath. Above the umbilicus, the sheath has three elements: the aponeurosis of the internal oblique splits to enclose the rectus muscle; the aponeurosis of the external oblique passes in front of the rectus to form part of the anterior sheath; and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis fascia passes behind to form part of the posterior sheath. The inferior margin of the posterior sheath is known as the semicircular line (semicircular fold of Douglas). Below the umbilicus, all three aponeuroses pass anteriorly, leaving a thin film of tissue posteriorly (Figs. 6-31 and 6-32).

|

Figure 6-31 The anterior portion of the rectus sheath is resected, revealing the fibers of the rectus abdominis muscle. Distal to the semicircular line, the linea alba (which is shown elevated by sutures) overlies the muscle fibers of the rectus abdominis but does not separate them. Proximal to the semicircular line, the linea alba separates the rectus abdominis muscles by attaching to the posterior rectus sheath, which begins at the semicircular line. |

The arrangement of the rectus sheath and the linea alba means that, in the upper half of the incision, the approach through fibrous tissue leads directly down to the peritoneum, whereas in the lower half, it leads to the rectus abdominis muscle. Because of this, it is easier to open the abdomen in the lower half of the incision (Fig. 6-33; see Fig. 6-32).

P.283

|

Figure 6-32 (A) The rectus abdominis muscle has been resected. The posterior aspect of the rectus sheath ends just distal to the umbilicus. Its distal edge is called the semicircular line. The linea alba attaches to the posterior rectus sheath, thus separating the rectus abdominis muscles proximal to the semicircular line. (B) Cross-section above the semicircular line. Note that the rectus abdominis muscles are enveloped by the posterior and anterior rectus sheaths and separated from each other by the linea alba. (C) Cross section below the semicircular line. The rectus sheath exists only anteriorly. Posteriorly is the transversalis fascia and peritoneum. |

P.284

|

Figure 6-33 The posterior rectus sheath has been removed to reveal the peritoneum and the abdominal viscera. |

The inferior epigastric artery supplies blood to the lower half of the rectus abdominis muscle. The artery lies between the muscle and the posterior part of the rectus sheath. If the surgical plane remains in the midline, this vessel should escape injury. If the artery is damaged when the rectus muscle is mobilized, it can be tied with impunity.

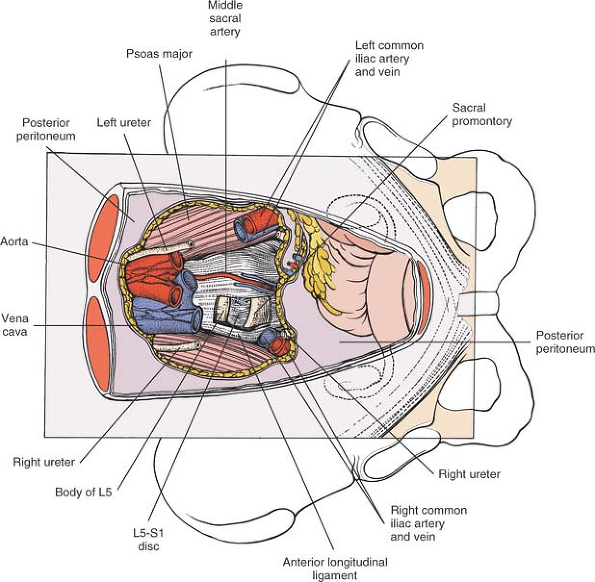

Deep Surgical Dissection and Its Dangers

Deep surgical dissection consists of freeing the distal ends of the aorta and the vena cava from the vertebrae in the L4-5 vertebral area. The aorta divides on the anterior surface of the L4 vertebra into the two common iliac arteries. Just below this bifurcation, the common iliac vessels divide in turn at about the S1 level into the internal and external iliac vessels. The internal iliac is the more medial of the two (Fig. 6-34).

The aorta and vena cava are held firmly onto the anterior parts of the lower lumbar vertebrae by the lumbar vessels. These segmental vessels must be mobilized to permit the aorta and vena cava to be moved (see Fig. 6-13). Because the arterial structures are easier to dissect and more muscular than are the thin-walled venous structures, the preferred approach to the L4-5 disc space is from the left, the more arterial side. The median sacral artery originates from the aorta at its bifurcation at L4 and runs in the midline, over the sacral promontory and down into the hollow of the sacrum (see Fig. 6-34). The lumbosacral disc usually lies in the V that is formed by the two common iliac vessels. Nevertheless, the level at which the vessels bifurcate may vary; on rare occasions, they may have to be mobilized to expose the L5-S1 disc space.

Note that the left common iliac vein lies below the left common iliac artery, whereas the right common iliac artery lies below and medial to the right common iliac vein. Therefore, special care must be taken

when mobilizing the left side of the vascular V, because the vessel closest to the surgery is the thin-walled vein, not the artery (Fig. 6-35; see Fig. 6-34).

P.285

P.286

when mobilizing the left side of the vascular V, because the vessel closest to the surgery is the thin-walled vein, not the artery (Fig. 6-35; see Fig. 6-34).

|

Figure 6-34 The abdominal viscera has been retracted proximally, and the retroperitoneum has been resected to reveal the great vessels at their bifurcation, the ureters, and the presacral plexus. |

A diffuse plexus of nerves exists in the presacral area. The nerves anterior to the L5-S1 disc are part of the superior hypogastric plexus which receives sympathetic innervation from T11 to L3 via the sympathetic chain and a plexus of nerves around the aorta. Injury to these nerves may cause ejaculatory dysfunction in men (retrograde ejaculation). More distally the plexus of nerve has parasympathetic contributions from the pelvic nerves (S2,S3,S4) which are important for erectile function in men. These nerves are more at risk with surgeries anterior to the mid and lower sacrum as well as low rectal and prostate procedures (see Figs. 6-34 and 6-35).15

|

Figure 6-35 Portions of the major vessels have been resected to reveal the underlying L5-S1 disc space, the sacral promontory, and its overlying presacral plexus. |

The ureter runs down the posterior abdominal wall on the psoas muscle. At the bifurcation of the common iliac artery over the sacroiliac joint, it clings to the posterior abdominal wall, held there by the peritoneum, and should be well lateral to the approach to the L5-S1 disc space. It may have to be mobilized for exposure of the L4-5 disc space (Fig. 6-36; see Fig. 6-35).

P.287

|

Figure 6-36 Osteology of the anterior aspect of the pelvis and lumbosacral spine. |

Anterolateral (Retroperitoneal) Approach to the Lumbar Spine

The retroperitoneal approach to the anterior part of the lumbar spine has several advantages over the transperitoneal approach. First, it provides access to all vertebrae from L1 to the sacrum, whereas the transperitoneal approach is difficult to use above the level of L4. Second, it allows drainage of an infection, such as a psoas abscess, without the risk of a postoperative ileitis. Because of the arrangement of the vascular anatomy of the retroperitoneal space, however, it is slightly more difficult to reach the L5-S1 disc space using the retroperitoneal approach.

The uses of this approach include the following:

Spinal fusion

Drainage of psoas abscess and curettage of infected vertebral body

Resection of all or part of a vertebral body and/or intervertebral disc and associated bone grafting

Biopsy of a vertebral body when a needle biopsy is either not possible or hazardous

P.288

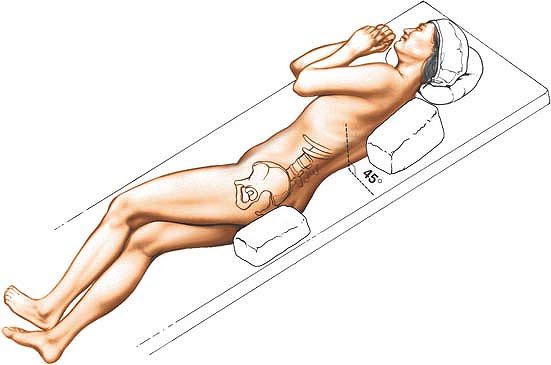

Position of the Patient

Place the patient on the operating table in the semilateral position. The patient’s body should be at about a 45° to 90° angle to the horizontal, facing away from the surgeon. Keep the patient in this position throughout the surgery by placing sandbags under the hips and shoulders or by using a kidney rest brace to hold the patient. The angle allows the peritoneal contents to fall away from the incision. Alternatively, place the patient supine on the operating table and tilt the table at 45° to the horizontal away from the surgeon. This position has the advantage of not putting the psoas muscle on stretch (Fig. 6-37).

The approach can be done with the left or right side up depending on whether the surgeon prefers to work on the “aortic side” or the “caval side.”

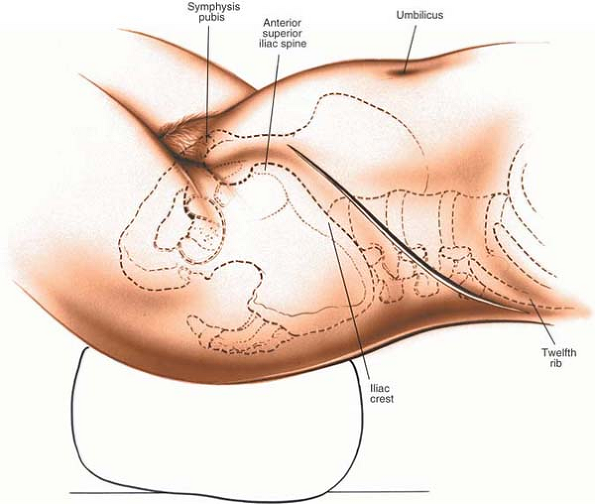

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

Palpate the 12th rib in the affected flank and the pubic symphysis in the lower part of the abdomen. Palpate the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle about 5 cm lateral to the midline.

|

Figure 6-37 Place the patient in the semilateral position for the anterolateral (retroperitoneal) approach to the lumbar spine. |

Incision

Make an oblique flank incision extending down from the posterior half of the 12th rib toward the rectus abdominis muscle and stopping at its lateral border, about midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis (Fig. 6-39).

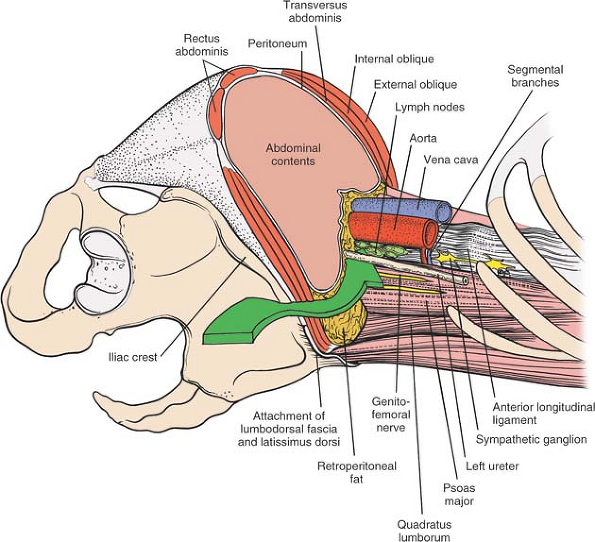

Internervous Plane

No internervous plane is available for use. The three muscles of the abdominal wall (the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis) are divided in line with the skin incision. Because all three muscles are innervated segmentally, significant denervation does not occur (Fig. 6-38).

Superficial Surgical Dissection

Deepen the incision through subcutaneous fat to expose the aponeurosis of the external oblique

muscle. Divide the aponeurosis of this muscle in the line of its fibers, which is in line with the skin incision. The muscle fibers of the external oblique rarely appear below the level of the umbilicus except in very muscular patients. If they are found there, the muscle should be split in the line of its fibers (Fig. 6-40).

P.289

P.290

muscle. Divide the aponeurosis of this muscle in the line of its fibers, which is in line with the skin incision. The muscle fibers of the external oblique rarely appear below the level of the umbilicus except in very muscular patients. If they are found there, the muscle should be split in the line of its fibers (Fig. 6-40).

|

Figure 6-38 The anterior abdominal musculature and viscera have been transected and removed at the level of the iliac crest. The arrow indicates the route of surgery between the peritoneum anteriorly and the retroperitoneal structures posteriorly. |

|

Figure 6-39 Make an oblique flank incision extending down from the posterior half of the 12th rib toward the rectus abdominis muscle. |

Next, divide the internal oblique muscle in line with the skin incision and perpendicular to the line of its muscular fibers. This division causes partial denervation, but if the muscle is closed properly, postoperative hernias can be avoided (Fig. 6-41). Under the internal oblique muscle lies the transversus abdominis muscle. It, too, should be divided in line with the skin incision to expose the retroperitoneal space (Figs. 6-42, 6-43, 6-47, and 6-48).

Using blunt finger dissection, develop a plane between the retroperitoneal fat and the fascia that overlies the psoas muscle (Fig. 6-44). Gently mobilize the peritoneal cavity and its contents and retract them medially (Fig. 6-45). Carry out this dissection from either the left lower quadrant or the right upper quadrant, depending on the side that needs to be exposed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree