1 The Medial Parapatellar Approach to the Knee

Patient Presentation and Symptoms

The medial parapatellar approach to the knee was first described by von Langenbeck1 in 1879. It is now often referred to as the “midline” approach, reflecting a modern modification placing the skin incision in the midline rather than medial to the patella.2 Patients who require the use of this approach present with myriad combinations of diagnoses and symptoms. In general, they may present with swelling, pain, deformity, limited range of motion, flexion contracture, instability, a mass lesion, or even a normal-appearing knee. Patients who present with fractures have obvious signs of acute trauma with swelling, crepitation, and false motion. Depending on the etiology of the patient’s complaints, presentation may include any or all of the above characteristics.

Indications

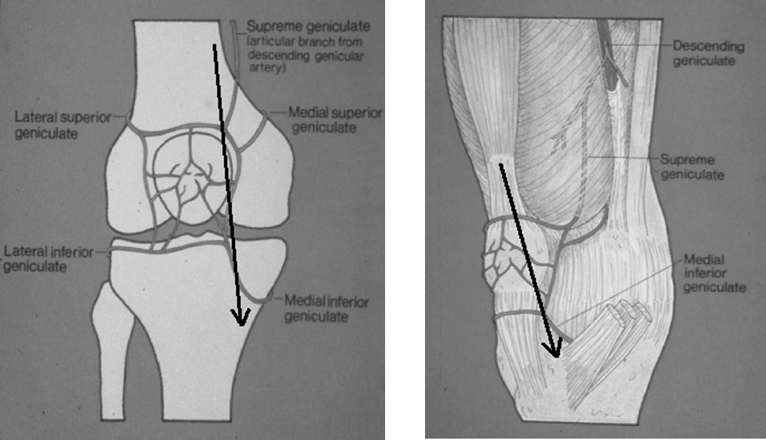

While this approach is considered primarily for total knee arthroplasty, it is suitable for many operations including open reduction and internal fixation of the distal femur, proximal tibia, or patella, and may also be used for femoral or tibial osteotomy. Surgery for recurrent dislocation of the patella as well as tibial tubercle osteotomy and anteriorizaion can also be performed through this approach. It is used for standard arthrotomy procedures including for infection, biopsy, chondrocyte resurfacing, allograft, and synovectomy. To perform a total synovectomy, however, accessory incisions may be necessary. In addition to the standard tricompartmental knee arthroplasty, variants of this procedure, like the unicompartmental knee replacement, can also be performed. A shorter version of this incision may be used for “minimal invasive” knee procedures. Surgical approaches differ in how they affect muscles, tendons, ligaments, and neurovascular structures (Fig. 1–1). Invariably some disruption of tissue occurs, and recently contemporary modifications of this approach have been developed, like the midvastus or subvastus variations, which are relatively more sparing to the muscles, nerves, and blood vessels and the extensor mechanism.3,4

To avoid problems with skin incision placement at future procedures, it is recommended that all reconstructive knee surgery be performed using an anterior midline skin incision if possible. At the very least, the incision should be compatible with a subsequent midline approach. Disastrous consequences such as skin ischemia, necrosis, or even full-thickness soft tissue loss are possible when a fresh incision is poorly placed near a prior, even very old incision. If the skin bridge between the two is too narrow or the blood supply is compromised, then wound-healing difficulties can be predicted and expected. Incision choices and plastic surgical options regarding skin coverage and potential hazards must be carefully considered.

Contraindications

Relative contraindications to the use of this incision would be loss of skin or subcutaneous tissue in the anterior and medial aspect of the knee in cases of burns, radiation, or skin loss that required extensive skin grafts. If the patient has had a myocutaneous flap, the midline skin incision may not be optimal. If the patient had prior medial and/or lateral parapatellar incisions that are vertical in nature and longer than 5 to 10 cm, then thought should be given to incorporating one of those incisions into either a medial or lateral skin incision. It is my practice to try to incorporate old incisions if they are longer than the above, no matter how many years in the past they may have been performed (Fig. 1–2). In general, the most lateral incision is safest because of the pattern of the blood supply. Prior horizontal incisions may be crossed or ignored without consequence. If the skin is tight, adherent, deficient, or otherwise compromised, a plastic surgery consult should be considered with the possible option of using a tissue expander,5 or a reconstructive procedure such as a myocutaneous flap. This approach is obviously contraindicated for procedures requiring access to the posterior region of the knee. After bony resection is performed during knee arthroplasty the posterior capsule and adjacent structures can be readily visualized.

Physical Examination

The surgeon must take a careful history and perform a thorough physical examination of the knee and the entire lower extremity including a detailed evaluation of the neurovascular status, motor and sensory function, pulses, and proprioception.6 Active and passive range of motion should be recorded as well as a thorough stability examination. The skin should be inspected for old incisions that may have faded and are not readily obvious. Patients often forget operations done many years in the past or as a child. Superficial varicosities, dermatologic lesions, and open ulcers must be looked for. Patients who exhibit severe flexion contractures may be candidates for a staged procedure. Patients with severe angular and rotational deformities may provide a challenge for the surgeon to close the skin and subcutaneous tissue. In these cases, a tissue expander might be considered.

Careful evaluation of the thigh and hip above, and leg and ankle below, must be performed to alert the surgeon to possible extraarticular deformities or prior surgery in these areas that may make exposure, stability, alignment, and the use of jigs difficult when performing arthroplasty.7 On rare occasions, a patient may present with an ipsilateral hip arthrodesis that can make the technical aspects of knee surgery difficult. If an acute fracture is present, then careful inspection for skin blisters and cellulitis must be performed. Patients with prior vascular surgery or vessel compromise may be at risk if a tourniquet is used.

Figure 1-2 A knee with prior incisions incorporated into the approach to avoid skin necrosis between the fresh incision and an old medial oblique incision.

Diagnostic Tests

The primary need for diagnostic testing prior to using a midline approach relates to skin viability. If other incisions are present, and doubt exists as to which one to use, a plastic surgery consultation should be obtained. At times angiography, duplex Doppler examination, or fluorescein dye examination may be needed.

Special Considerations

Most of these considerations have been addressed above. A patient with extraarticular deformities or severe intraarticular deformities can present problems with alignment, stability, and jig placement7 as well potential problems in wound closure and healing.5 Patients with periarticular scars or incisions should be evaluated for possible use of a tissue expander or an alternative incision to the anterior midline approach. Rarely, a “sham” incision can be considered, incising the skin down to the capsule, then closing to observe the wound and assess healing before doing a definitive procedure.8 Patients who have had old infections, radiation therapy, or prior plastic surgical procedures may also be candidates for these options. The very obese patient should be evaluated for neurovascular status, joint landmarks, and thigh girth size to determine whether tourniquet placement will be feasible. In the obese, patella eversion may be difficult or impossible unless a pocket is made in the subcutaneous tissue. Larger than normal retractors and extra surgical assistants can be helpful. This approach may not be suitable for the extremely stiff or ankylosed knee.

Preoperative Planning and Timing of Surgery

Patients must be screened before any anticipated surgery to rule out intercurrent adjacent or remote problems including infection, cellulitis, edema, and skin lesions such as pustules, ulcers, psoriasis, eczema, and superficial varicosities. Patients with acute inflammation around the knee with cellulitis or blisters such as seen following fractures should have surgery deferred until the condition is resolved. Surgery on patients who have been taking aspirin or other medications that can affect wound healing and bleeding times should be deferred until it is safe to proceed. Alternative incisions and special evaluations have been noted in sections above.

Special Instruments

Depending on the planned procedure, several devices, instruments, and retractors can be helpful. A bolster made of rolled sheets wrapped with an elastic bandage approximately 9 inches in diameter is placed under the knee for the incision (to stretch and shorten the incision) and under the Achilles region for other parts of the procedure that may require full or hyperextension. The bolster behind the knee is also helpful for closure to help position the patella and extensor mechanism. I prefer to use of blunt rakes in the subcutaneous tissue because they cause less damage to the adipose layer. In the obese patient, large finger-like “hay rakes” can be helpful. I have also used the Charnley initial incision hip retractor to help provide adequate exposure of deep and subcutaneous tissue. Once inside the joint, pointed 90-degree angled Hohmann retractors help to widely expose the joint margins when inserted medial to the medial meniscus and lateral to the lateral meniscus. If a medial ligament release is performed as in a total knee arthroplasty, the medial retractor is placed at the metaphyseal region of the tibia, retracting the deep and superficial medal collateral ligament (MCL), taking with it the medial meniscus. In cruciate retaining arthroplasty, a double- or singlepointed posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) retractor placed behind the tibia cradling the PCL is helpful to bring the tibia forward without injuring the ligament. Periosteal elevators can be useful to expose the fascia and quadriceps expansion before incising and also to expose the bone in the supracondylar region so that the femur can be adequately assessed for size, and to prevent notching if knee arthroplasty is being performed. Curved and straight osteotomes are helpful to remove overhanging and impinging osteophytes. They may also be used to strip the periosteum and aid in ligament releases. Curved chisels are especially helpful to remove posterior femoral condylar osteophytes and for releasing the posterior capsule if necessary in cases of severe flexion contracture. Electrocautery is helpful and may be used to subperisosteally strip the medial and lateral ligaments as well as the iliotibial band. Most surgeons use a tourniquet for reconstructive surgery, and all sizes including 24, 34, and 42 inches should be available. The tourniquet should be calibrated to ensure proper pressure. A 12- to 18-inch-long sandbag taped to the operating table on top of the mattress and sheet at a point between the tibial tubercle and the distal pole of the patella is helpful for controlling the flexed limb during the surgical procedure. Hyperflexion of the knee places the foot behind the sandbag, stabilizing the limb and freeing up a hand of an assistant. If the insertion of the patella tendon is at risk for avulsion, then a nail or pin should be inserted to prevent this serious complication.

Anesthesia

We perform virtually all reconstructive knee procedures using a regional block such as epidural or spinal anesthesia. If this is contraindicated or impossible to achieve, or if the patient so desires or if it is medically necessary, then general anesthesia is used. If epidural anesthesia is used, the catheter is often left in place for pain control. “Local” anesthesia, while effective for some procedures coupled with a monitored anesthesia care, is not suitable for major reconstructive surgery. While theoretically, reconstructive procedures can be performed under sciatic and femoral nerve block, we have had no experience with this technique. However, we do use femoral nerve block with or without an indwelling catheter postoperatively for pain control.

Patient and Equipment Positions

Using the anterior midline approach to the knee usually necessitates placing the patient in the supine position. The patient is appropriately padded and secured. Once the patient is surgically prepared and draped, the operating table is lifted to a comfortable height for the surgeon. Because the limb tends to lie in external rotation, the table is often tilted 5 to 10 degrees toward the contralateral side to allow the patella to point straight up. If a tourniquet is used, it is placed as high as possible, over several layers of cast padding. Tincture of benzoin or some other similar preparation may be applied first to the skin if the tourniquet tends to slip. After the benzoin is allowed to dry, the residual stickiness adheres to the cast padding. Certain procedures may also be performed with the leg hanging over the table as in an arthroscopic procedure. If needed, a sandbag and bolster are used as described above.

Surgical Procedure

If a tourniquet is to be used, it is usually applied before preparation and draping. It can be done afterward if a sterile tourniquet is used. The limb is surgically prepared by elevating the limb and washing it from the lower edge of the tourniquet to the toes. The limb is then dried and painted with a povidone—iodine solution. An impervious surgical stockinette is placed over the foot and ankle. A towel is placed snugly around the lower end of the tourniquet to isolate it. The stockinette is then rolled all the way up over the tourniquet and up into the groin. Plastic U-shaped drapes are placed from posteriorly and anteriorly distal to the tourniquet and snugly secured. An extremity drape with an aperture through a rubber dam is then applied. The foot and ankle is wrapped snugly with an adherent elastic bandage. The anterior and posterior portion of the stockinette is cut out from the midportion of the tibia to just below the towel surrounding the tourniquet. The skin is marked with a sterile marking pen with multiple horizontal lines from above the knee to below the knee to facilitate skin closure. Two clear adhesive skin drapes are used, one posteriorly and then one anteriorly. The redundant edges medially and laterally are removed with scissors. The elastic bandage is then wrapped to incorporate the lower portion of the adhesive drape. Another clear adhesive drape is then placed to cover the drapes below the limb to prevent fluid accumulation and possible penetration. The limb is then elevated and an Esmarch bandage is applied from the toes to the groin to exsanguinate the limb. The Esmarch would not be used if infection or tumor was present, in which case the limb would be simply elevated over 45 degrees for at least 5 minutes. The tourniquet is inflated. If the surgeon chooses, the knee can be fully flexed before inflation. In our experience the tourniquet is placed very high in the thigh and flexion of the knee before inflation has not been necessary. We have measured passive “drop” flexion with or without flexion of the knee prior to inflation and it has been virtually the same.

Now that the limb is completely prepared and draped and the tourniquet is inflated, the bolster is placed beneath the knee. This places the knee in approximately 45 to 60 degrees of flexion. An alternative method is to hyperflex the knee and make the initial incision in full

flexion. In this way, especially in the obese patient, the subcutaneous tissues fall away as the incision is developed. It also has the added benefit of shortening the length of the incision.

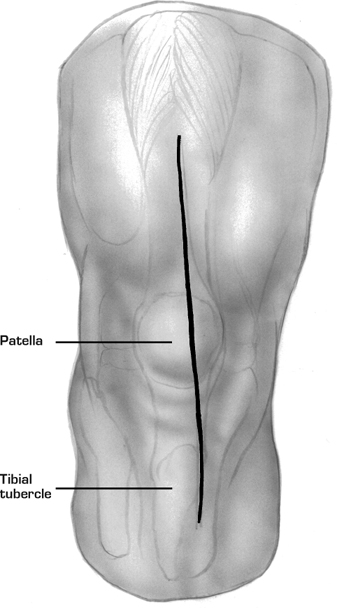

The anatomic landmarks including the patella, tibial tubercle, and patella tendon are marked. The classic incision begins approximately 4 to 6 fingerbreadths above the superior pole of the patella and ends approximately 2 fingerbreadths below the tibial tubercle. The incision is usually placed slightly to the medial aspect of the midline to avoid placement directly over the tibial tubercle (Fig. 1–3). The size of the incision should vary depending on the size of the patient and the anticipated exposure needed. So-called “minimal incision surgery” or “minimally invasive surgery” uses a shortened version of this approach. If a knee arthroplasty is being performed and the patient has a significant varus or valgus deformity, consideration is given to making the skin incision in the line of the deformity rather than straight to end up being straight after the arthroplasty is performed.

The skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised and hemostasis is achieved. Retractors are placed, but no undue tension should be placed on the skin or subcutaneous tissue. No flaps are created until the incision is carried below Scarpa’s fascia. If the incision has been made in flexion, once Scarpa’s fascia is incised and the quadriceps and rectus tendon is identified and dissected, the knee can be placed into extension with a bolster beneath the distal calf. Scarpa’s fascia is incised from the proximal portion of the incision down to the patella. At this point, the prepatellar bursa is encountered. I prefer to leave the bursa intact, but another option is to split the bursa longitudinally. If this is chronically inflamed or calcified such as in gout, then the bursa is excised. The bursa blends tightly with the fascia overlying the inferior patella and often cannot be completely dissected free. The paratenon of the patella tendon is identified and the subcutaneous tissue is bluntly or sharply dissected free from this. Often adhesions are present between the subcutaneous tissue and the quadriceps mechanism, especially with a valgus deformity on the lateral side that can tether the patella. These are incised if needed.

Once the superficial fascia is opened, there are usually blood vessels on the medial aspect on the upper tibia over the pes tendons, and these are cauterized. There can be several perforating vessels from the quadriceps itself and the rectus tendon to the subcutaneous tissue that must be cauterized as well. Appropriate retractors are placed in the subcutaneous tissue to expose the quadriceps expansion. In the obese patient, large, blunt “hay” rakes are used. The retinaculum and rectus tendon is cleansed with an elevator, and horizontal markings are made at intervals with a sterile marking pencil across the rectus tendon, across the medial edge of the patella, and at the edge of the patella tendon. These marks will help in reapproximating the tissues upon closure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree