The Evolution of Hip Arthroscopy

Giles H. Stafford

Ajay Malviya

Richard N. Villar

Introduction

Over a period of approximately 30 years, hip arthroscopy has evolved from an experimental technique performed by a handful of surgeons worldwide, to a widely recognized and increasingly popular procedure. The arthroscope may be used in the treatment of many disorders in and around the hip joint, the indications constantly expanding and being refined. This chapter describes the birth of arthroscopy as an entity, and then more specifically its use in the hip. We describe the various phases of the development of hip arthroscopy, with specific reference to technical advances and published literature. We have sought the memories of a few of the founding fathers of the procedure, plus those who have been involved in the design and manufacture of the hip-specific instrumentation. As a result, we hope that this chapter provides the reader with a comprehensive review, from the birth of hip arthroscopy through to its use in the present day.

A Brief History of Arthroscopy

Philipp Bozzini, who lived between 1773 and 1809, developed the very first endoscope in Germany (1). His instrument, named the “Lichtleiter” (light conductor), was presented in 1806. The Lichtleiter allowed inspection of many cavities such as the ear, urethra, rectum, female bladder, cervix, mouth, nasal cavity, or wounds. The development of endoscopy was limited, however, because of the poor quality of both lighting and optical technology. Different methods of illumination were tried in the mid 19th century, either by transmitting the light from burning turpentine via mirrors, or using a red-hot, glowing wire. The major breakthrough, however, came with the invention of the light bulb in 1880 by Thomas Edison. This allowed the development of endoscopes, which at the time were mainly used to visualize the bladder.

It is accepted that the first published report of looking inside a joint with an endoscope was by Severin Nordentoft, a Danish physician working in Aarhus (2). He presented his work in 1912, at the 41st Congress of the German Society of Surgeons in Berlin. He used a homemade “trokart-endoscope,” which had a 90-degree lens, and through this he presented a detailed description of the knee joint. As irrigation fluid, he used either saline or a boric acid solution. Nordentoft was the first man to use the phrase “arthroscopy.” His invention did not capture the imagination of the doctors of the time, and his presentation, although published, faded into obscurity.

Around the same time, another endoscope was being developed in Stockholm by Professor Hans Christian Jacobaeus. His design was broadly similar to Nordentoft’s, and published its use in 1913 (3). Jacobaeus used his device to divide pleural adhesions during the treatment of tuberculosis. He quickly became well known as a result, leading the “Jacobaeus endoscope” to go into mainstream production (4).

Professor Kenji Takagi was the next person to describe arthroscopic examination in 1918. Working from Tokyo, he used a cystoscope to examine tuberculous knees (5). At that time, tuberculosis in this joint resulted in an ankylosed knee, considered both a serious social and physical disability to patients in Japan. Takagi to refined a cystoscope so that by 1931 he had developed the 3.5-mm No. 1 arthroscope. Takagi created 12 different arthroscopes, No. 1 to No. 12, with varying angles of view, along with operative instruments small enough to perform rudimentary surgery, such as biopsy within the knee joint. Takagi’s progress was preempted, however, because of World War II.

In the Western world, a Swiss physician, Eugen Bircher, performed an arthroscopy in 1921 using a Jacobaeus endoscope. Bircher published his articles regarding arthroscopy of the knee, referring to this technique as “arthroendoscopy” (6). Bircher used arthroendoscopy as a prelude to arthrotomy. Comparable to laparoscopy, he filled the joint with nitrogen or oxygen primarily to visualize and diagnose such conditions as “internal derangement.” His articles published between 1921 and 1926 were based on approximately 60 arthroendoscopic procedures. However, by 1930, Bircher abandoned arthroendoscopy in favor of air arthrography, citing better visualization using contrast media with radiographic images (6).

Following this, in 1925, Professor Kreuscher (7) published his work on meniscal injuries, titled “Semilunar cartilage disease—A plea for the early recognition by means of the arthroscope.” Kreuscher worked in Chicago, but he may have been influenced by Nordentoft’s work, as he completed a fellowship in Berlin during 1912. It is thought that he may have used the Jacobaeus endoscope, as a colleague of his in the same hospital also published on its use in the abdomen the same year (8). Kreuscher experimented with different

methods of distending the knee using gases such as nitrogen or oxygen, and fluids such as formaldehyde.

methods of distending the knee using gases such as nitrogen or oxygen, and fluids such as formaldehyde.

In 1929, Burman (9) independently conceived the idea that it might be possible to view the interior of a joint with a special device. At the time, Burman was a resident at the Hospital for Joint Diseases in New York. He commissioned the design and fabrication of such an instrument from Reinhold Wappler at the American Cystoscope Manufacturing Institute (ACMI), who completed it in 1930. A description from Wappler follows, “the arthroscope consists of a sheath with a point serving as a trocar. An extremely small lens system with illuminator fits within the said sheath. It permits visualising of narrow spaces either air or water filled. The removal of the telescope permits washing out of opaque fluid contained in hollow bodies to be examined, until the distending fluid is clear and a good view can be had. The front lens is shaped so that the inlet pupil is on the periphery and the little lamp on the end is just on the outside of the field of vision.” He goes on to describe the diameter of the trocar as 4 mm, with a 3-mm telescope. “Note should be made of the space between the trocar and the telescope, which allows irrigation of the joint examined. The faucets are attached to the trocar and may be used as either as inlet or as an outlet.”

Unfortunately, there were not enough cadavers available at the New York Medical School, and so Burman set sail for Germany on a travelling scholarship. He resumed work at the Krankenhaus der Freidrichstadt-Dresden under the supervision of Dr Georg Schmorl. Following his return to New York, Burman published a comprehensive study describing the arthroscopic appearances of the hip, knee, ankle, shoulder, elbow, and wrist. Burman decided that arthroscopy of smaller joints was not advisable because of the diameter of the instrument. It was not until the completion of his study did he become aware of the work done previously by Bircher, and in his publication he concedes this.

Burman was, however, the first to describe hip arthroscopy. He stated “visualization of the hip joint is limited to the intracapsular part of the joint. It is manifestly impossible to insert a needle between the head of the femur and acetabulum.” Burman does not describe attempting distraction of the hip, but does say “we have found it difficult to move the joint because of rigor mortis fixing the joint solidly.” Burman also describes his preferred portal placement for hip arthroscopy as “anterior paratrochanteric,” a portal much used today. He also states that “a special long trocar, with a correspondingly long telescope” at least 15 cm in length, should be used for the hip joint. As such, Burman can undoubtedly be called the founder of hip arthroscopy. Michael Burman completed his residency, and subsequently worked as an orthopedic surgeon at the Hospital for Joint Diseases his entire career. He continued his work on arthroscopy, but this was unfortunately never published.

World War II delayed advancements in medical science, and it took 16 years after the end of the war to resume publication of articles reporting progress in arthroscopic surgery. In fact, after the work of Burman, interest in arthroscopy was lacking in North America until the 1960s. However, in Japan, a protégé of Takagi’s, Watanabe (10), established himself as the founder of modern arthroscopy by developing sophisticated endoscopic instruments, using electronics and optics, which became popular in Japan in the post–World War II era. Watanabe’s No. 21, developed in 1959, would be the instrument by which North American surgeons would develop their skills in surgical arthroscopy. Yet, in spite of increasing improvements, the No. 21 arthroscope had its disadvantages; the light carrier would short circuit and the bulb would occasionally shatter in the knee.

It would not be until the development of cold light fiber optics by Professor Harold H. Hopkins, that endoscopes would become safe and dependable. This led to the development of the “Hopkins rod-lens endoscope” first manufactured by Karl Storz in 1965. Watanabe’s design was also eventually mass produced, named the “Needlescope”; it was made widely available in 1971 by Dyonics (Dyonics, Andover, MA, USA).

Dr Robert Jackson, a Canadian surgeon working in Toronto, visited Watanabe in 1964 (11). Following his visit, Jackson started knee arthroscopy and followed on from this to present his work to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in the United States in 1968 (12). He was invited to give the first instructional course by the Association the following year. The interest in arthroscopy now gathered momentum, and the International Arthroscopy Association was founded in 1974. The development of instruments also began to pick up speed, with the first motorized shavers being developed by Dyonics in conjunction with Dr Lanny Johnson in 1977. Johnson started his own company in 1980, Instrument Maker, manufacturing other arthroscopic tools, and he eventually sold this to Smith & Nephew (Smith & Nephew, Andover MA, USA) in 2002.

Modern Hip Arthroscopy—Pre-1990, the Introductory Period

The introduction of hip arthroscopy as a clinical entity was gradual, but has recently expanded, as knowledge of pathology and advances in instrumentation make the procedure more attractive. It is difficult to ascertain who was the first to introduce an arthroscope to the hip, although the earliest publications are by Aignan (13), and describe arthroscopic synovial biopsy in the mid-1970s.

Two early pioneers of hip arthroscopy, Lanny Johnson and Ejnar Eriksson, were working independently of each other in the United States and Sweden in the mid-1970s (14). Dr Johnson was the first to put together a course on hip arthroscopy, held in Michigan in 1976. He used a knee arthroscope, with the patient in the supine position. Johnson discovered that by injecting fluid into the hip, less distraction was necessary to gain safe access. He also used methylene blue in the hip to better visualize degenerative articular cartilage. Johnson was mainly using the arthroscope for diagnostic purposes, and was able to visualize the whole hip, including the ligamentum teres. He did, however, perform some therapeutic procedures via a second portal, such as loose body removal, osteophyte debridement, chondroplasty, and iliopsoas debridement (personal communication).

However, the first English language publication in the modern era was by Gross (15), who described hip arthroscopy in children post slipped upper femoral epiphysis in 1977. This was followed by a paper by Shifrin and Reis (16),

who described the use of an arthroscope to remove a loose body in the acetabular component of an irreducible total hip replacement in 1980. Vakili, Salvati, and Warren (17) then described removal of a foreign body within the acetabular cup of a total hip replacement using an arthroscope later the same year. Holgersson et al. (18) followed this with diagnostic hip arthroscopy in children with juvenile chronic arthritis in 1981. Also in 1981, Johnson published “Hip joint in diagnostic and surgical arthroscopy,” where he described his technique (19).

who described the use of an arthroscope to remove a loose body in the acetabular component of an irreducible total hip replacement in 1980. Vakili, Salvati, and Warren (17) then described removal of a foreign body within the acetabular cup of a total hip replacement using an arthroscope later the same year. Holgersson et al. (18) followed this with diagnostic hip arthroscopy in children with juvenile chronic arthritis in 1981. Also in 1981, Johnson published “Hip joint in diagnostic and surgical arthroscopy,” where he described his technique (19).

Eriksson and Sebik (20) discussed the benefits of gas over fluid media in 1982, and were also the first to describe the “suction seal” of the hip joint. In 1986, Eriksson et al. (21) also measured the forces need to distract the hip to allow access to the area between the femoral head and acetabulum, between 300 and 500 Newtons (N) in an anesthetized patient, and up to 900 N if awake. In the same paper, Eriksson also again discussed gas and fluid media, concluding that gas was preferable for diagnosis, but fluid for operative procedures.

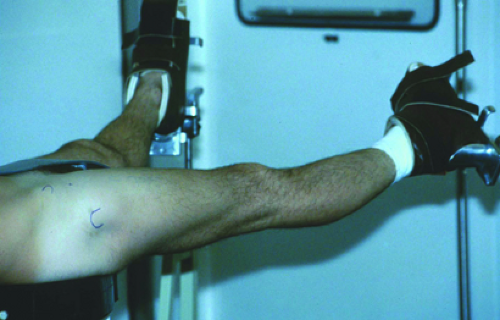

Both Johnson and Eriksson performed their hip arthroscopy procedures with patients supine, using a fracture table for distraction of the hip (Fig. 22.1). Dr James Glick, who had started hip arthroscopy in the supine position after discussion with Johnson in 1977, was the first to convert to the lateral position in 1982 with his colleague, Dr Thomas Sampson. One of the reasons for this was because of a particular case where they found the standard arthroscope insufficient length to enter the hip joint in a well-covered patient (personal communication). They hypothesized that in the lateral position, the skin-to-joint distance would decrease as a result of gravity. Glick used a combination of weights and pulleys for distraction, and as an evolution of this, went on to help design the first specific hip arthroscopy distractor, subsequently manufactured by Arthronix (Arthronix, New City, NY, USA) in 1986 (Fig. 22.2).

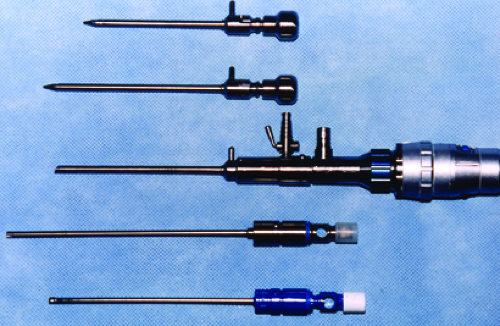

The first hip arthroscopists used the standard 30-degree knee arthroscope to visualize the inside of the hip joint. The introduction of the 70-degree arthroscope was not until later, and Glick attributes its development to J.W. Thomas Byrd. Byrd was also using the standard length arthroscope in his early days. The reasons for this was that it was not thought to be commercially viable to manufacture specific hip arthroscopes, as only a few surgeons of the time were performing the technique, and it was not until hip arthroscopy gained more momentum that specific instruments went into production. Glick et al. (22) described the special extra-long arthroscope manufactured for him by Dyonics, but also the extra-long instruments needed in some cases, which have now become the standard for arthroscopic access to the hip. He also went on to help design the first specific hip arthroscopy instruments, manufactured by Stryker (Stryker Endoscopy, San Jose, CA, USA) and known as the “Glick Hip Set.” Byrd was also involved in the design of hip–arthroscopy-specific instruments, and the “Byrd set” was manufactured by Smith & Nephew (Fig. 22.3).

Glick et al. (22) published their series of eleven hip arthroscopies with the patients in the lateral decubitus position in 1987. In this paper, they describe the anatomy and technique, as well as the instruments mentioned previously. However, there remains much good-humored debate among hip arthroscopists about the best approach, supine or lateral decubitus. Byrd (23) published a series of twenty cases in the supine position. He argues that in the supine position, the surgeon can still use the standard fracture table and the orientation is easier for surgeon and staff. There are merits and drawbacks of either approach, and the choice is down to the preference and training of the operating surgeon.

Hawkins (24) published a series of 12 cases of hip arthroscopy in 1989, following a mini-arthrotomy. At this time, the indications for hip arthroscopy were mainly diagnostic, with therapeutic procedures being largely limited to removal of loose bodies, biopsy, and synovectomy.

The Consolidation Period, 1990 to 2000

As interest in hip arthroscopy grew, as did the need for further understanding of the arthroscopic anatomy and pathology that may be seen. Dvorak et al. (25) published the arthroscopic anatomy of the hip in 1990, which described the views from the different portals in use at the time. This was followed by the first textbook describing hip arthroscopy and the conditions that may be treated at the time (26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree