Chapter 2 The Epidemiology of Lupus

The Fundamentals of Epidemiology

The earliest reports on SLE were based on clinical and pathologic experiences from relatively small numbers that distinguished the disorder from other connective tissue diseases and established a relationship to such factors as age and sex, photosensitivity, trauma, surgery, infection, and chemotherapy.1 Population studies of SLE were felt to be more feasible in the early 1950s with the advent of the LE cell test, a serologic test that was hoped to have the ability to identify cases uniformly or without characteristic features. Reliance on the LE cell test to diagnose SLE began to diminish after a few years as its poor specificity was better appreciated2 and its lack of sensitivity to identify the broad spectrum of SLE patients became evident. To this day, a widely available test that is both sensitive and specific for SLE on a population level does not exist. Nevertheless, many studies have attempted to define the frequency of disease.

Case Definition

Classification criteria are designed to provide consistency across study populations and are appropriate for epidemiologic purposes. Several exist for SLE.3 The most universally accepted criteria have been those endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). The former American Rheumatism Association, now known as the ACR, established the first classification criteria for SLE in 1971. These criteria, which included the LE cell test, allowed for standardized classification of patients. The earliest studies adhered generally to the 1971 criteria but did not strictly apply them.4 In 1982, the criteria were revised to include further advances in serologic testing—for antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA)—as well as improved biostatistical techniques. In 1997, the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the ACR reviewed the 1982 criteria and recommended that a positive result of LE cell preparation be removed and replaced with the finding of antiphospholipid antibodies. These updates were based on committee consensus but were never subjected to rigorous validation testing.

Although the use of ACR criteria enhances the comparability of research studies, there are also drawbacks. Notably, the sensitivity of the 1982 criteria has been shown to be only 83% in an external population compared with 96% in the test population. Additionally, the criteria tend to be skewed toward limited detection of mild cases of SLE, or incident cases at early stages of their prodrome. Not only would the population size be underestimated with the criteria but the cases would also be biased toward those of longer disease duration and greater severity. Four of the 11 ACR criteria are overly biased toward cutaneous manifestations of SLE, even though every other organ system has one. The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) group has revised the ACR SLE classification criteria and validated alternative criteria in order to improve clinical relevance, meet more stringent methodology requirements, and incorporate new knowledge in SLE immunology since 1982.4a It will be important to externally compare these and any new criteria with the existing ACR criteria. Cutaneous lupus does not have classification criteria. Biopsies of the skin may not be available and are not specific.

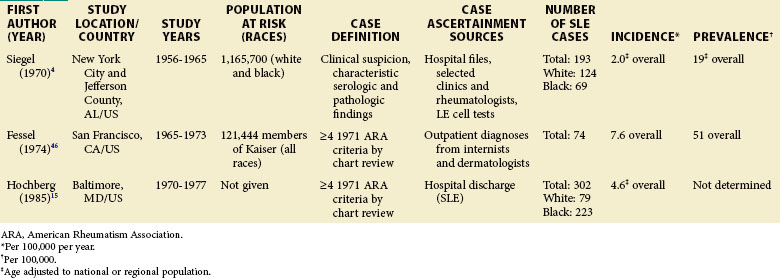

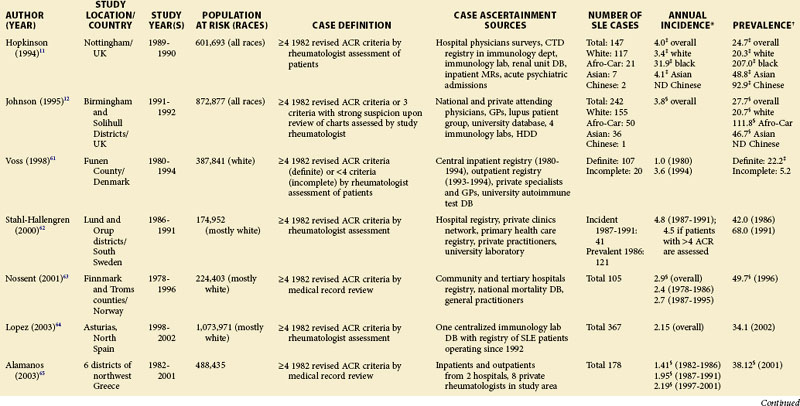

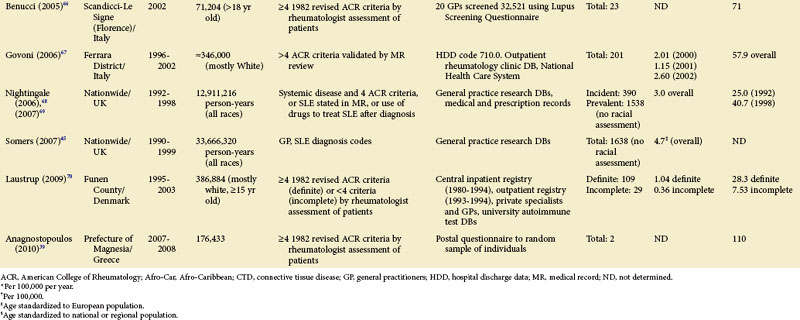

Each scientific advance that leads to improved laboratory techniques and/or any greater public awareness of the disease can make a profound impact on our ability to define and ascertain cases and, therefore, the rates of disease. Comparisons of earlier studies with later ones are difficult. Therefore, epidemiologic studies utilizing case definitions prior to the 1982 ACR criteria are presented separately (see Table 2-1).

Case Ascertainment

Administrative data are often used to find patients with potential lupus. Using such information can be an efficient way to ascertain cases throughout large health systems and different levels of care. However, the validity and accuracy of the data need to be better determined in different health systems. This can be achieved by utilizing multiple sources and adjusting for error in each.5 Self-reported physician diagnosis of SLE has been used but was found to be unreliable after a review of a sample of available medical records or asking whether the patients take lupus medications.6,7 With the advent of electronic medical records in certain countries, there may be ways to query large systems with improved accuracy.

Although a number of different sources may be utilized to find cases, the final result is likely to be an underestimate. Capture-recapture methodology of data analysis aims to correct for this by taking advantage of duplicate cases to mathematically determine the degree of overlap between the sources. The result is an alternative estimate that includes potentially missed cases and should be incorporated whenever possible.8

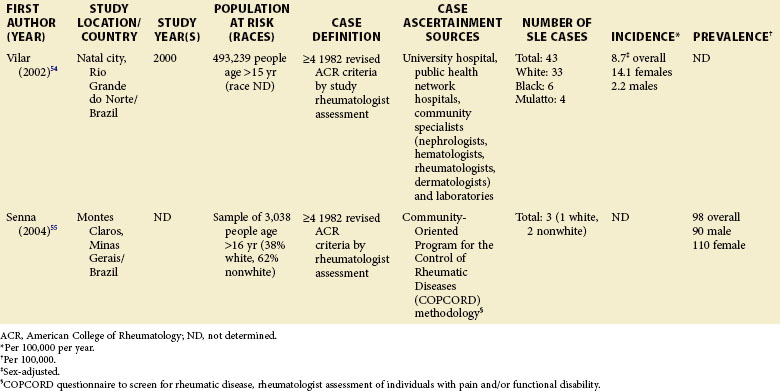

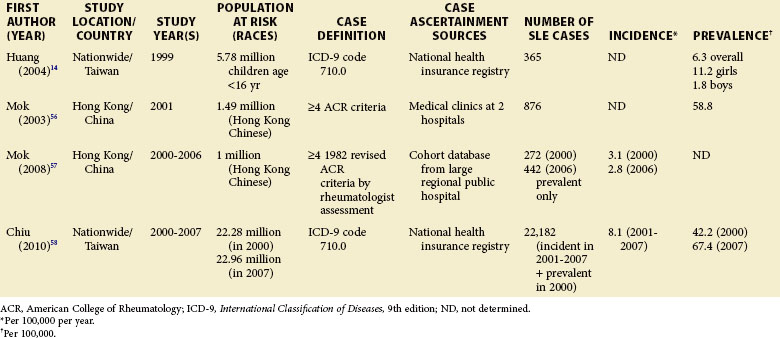

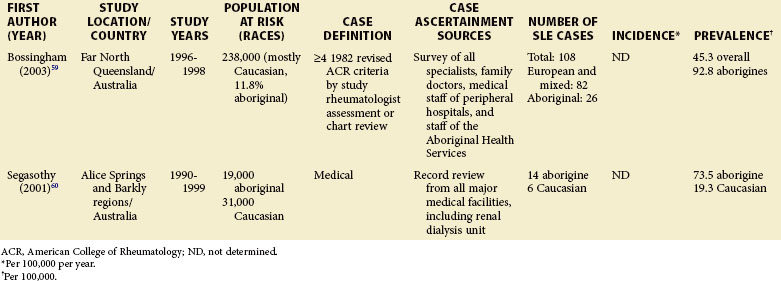

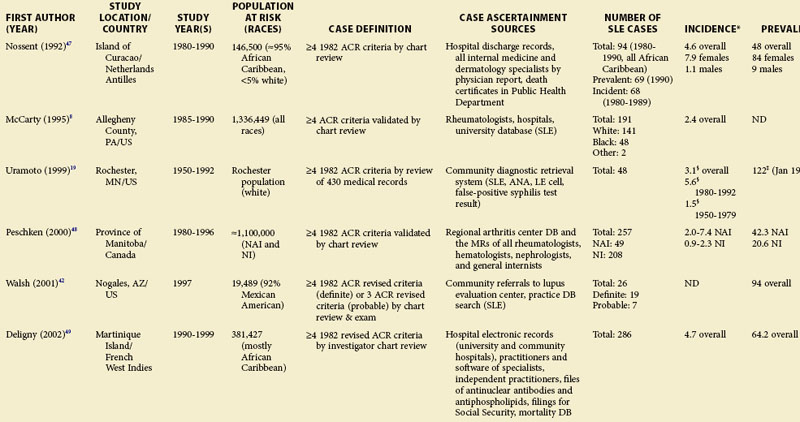

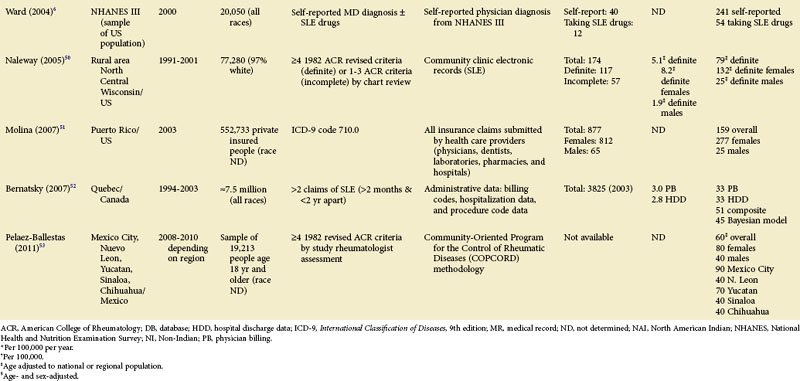

Although much of the epidemiologic data have been from the more developed Western nations, relatively little has been known about other countries (Tables 2-2 to 2-6). An enduring epidemiologic question is how African, Asian, and Hispanic ancestry influences the risk for SLE. There are no reports of significant rates of SLE in rural Africa or Asia, a situation that could, in part, be the result of underreporting due to a lack of health resources and expertise as well as other, more prevalent competing health issues. Further confirmation of the underlying indigenous rates of disease in these ethnic groups is needed. The strikingly increased rate in Americans of African ancestry has suggested that an SLE “prevalence gradient” exists,9 whereby genetic admixture and environmental factors are thought to raise the risk of SLE in people of African descent living in industrialized nations.

TABLE 2-2 Population-Based Studies of the Incidence and Prevalence of SLE in North America, Including the Caribbean and Puerto Rico

Population at Risk

Special attention should be given to different ethnic groups with appropriate stratified rates. Data summarized in the mid-2000s showed that some of the lowest rates are seen among Caucasian Americans, Canadians, and Spaniards with incident rates of 1.4, 1.6, and 2.2 cases per 100,000 people, respectively.10 In predominantly Caucasian populations, who tend to have less severe and longer duration of disease, prevalence rates may be underestimated if milder cases or patients in remission are not ascertained. The data from Northern European countries are excellent resources for understanding the burden of SLE in this group. Incident and prevalence rates are consistently higher among those of African, Hispanic, or Asian descent in studies from different countries. In England, for example, the annual incidence rate in people of Afro-Caribbean ethnicity has been reported to be 31.9/100,000 for both genders in Nottingham, and 25.8/100,000 for females in Birmingham, whereas whites showed rates of 3.4/100,000 and 4.3/100,000, respectively.11,12

Recent migration patterns may also introduce biases that are rarely accounted for in population-based studies. In most European countries, where the net migration rate is usually ±1% per year, the overall prevalence estimates may not appear to be affected significantly by migration. However, they may be susceptible to the “healthy migrant effect.”13 An area of south London showed much higher prevalence of SLE in recent immigrants from West Africa (110/100,000) than in European women (35/100,000), although the prevalence in West African women was lower than in Afro-Caribbean women living in the same area (177/100,000). Because most West Africans migrated as adults, individuals with SLE are thought to have been less likely to leave their countries. On the other hand, Afro-Caribbeans were predominantly either born in the United Kingdom or had migrated as children and so their migration patterns were less likely to have been influenced by the disease. Continued epidemiologic evaluation and surveillance of the prevalence rate of SLE in the second generation of West African immigrants could help confirm this migration bias. In the United States, the undocumented Hispanic population is mobile and may move depending on a variety of different factors (economic, legislative, etc.). Immigrants with SLE may cluster in areas with better access to medical care. On the other hand, their numbers may be underestimated because they have more barriers to health care in general than the native population. Evaluation of migration rates should be considered and, when possible, adjusted for.

Pediatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Although children have been identified in population-based epidemiologic studies of SLE, many have not been focused or consistent. Pediatric SLE represents an important subgroup of SLE that deserves special attention. One challenge is that there is no consensus age range. Depending on factors in each country, studies define pediatric patients anywhere from 14 to 18 years old. In general, they are found in pediatric hospitals and in specialist practices (pediatric rheumatologists, nephrologists, etc.). It is important that these sources are included in case ascertainment if pediatric rates are to be valid. Some studies from the United States and Europe included pediatric patients from a wide range of ages, whereas others only included those 15 years of age and older. A nationwide, prospective, population-based study from Taiwan reported a prevalence rate of 6.3/100,000 children younger than 16 years, and the at-risk population was 5.78 million.14 Though some U.S. studies do report pediatric SLE rates, either case ascertainment efforts have not been broad enough or the numbers have been too small to be considered valid. An early study of Alabama and New York City reported an incidence of 6.3/1,000,000 during a 10-year period for white girls younger than 15 years.4 This was based on only two hospitalized patients, with none being reported as black. A study of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, determined an incident rate of 3.0 and 3.4/100,000/year among white and black females between the ages of 12 and 19 years, respectively. This rate was based on 12 white and 3 black children with the disease. In a rural region of Wisconsin, only 2 new patients younger than 19 years were identified between 1991 and 2001. The lowest annual incidence rate, 0.5/100,000/year, was reported in Baltimore, where 10 black patients younger than 15 years old were identified from hospital discharge records.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree