Chapter 53 Novel Therapies for SLE

Biological Agents Available in Practice Today

Introduction

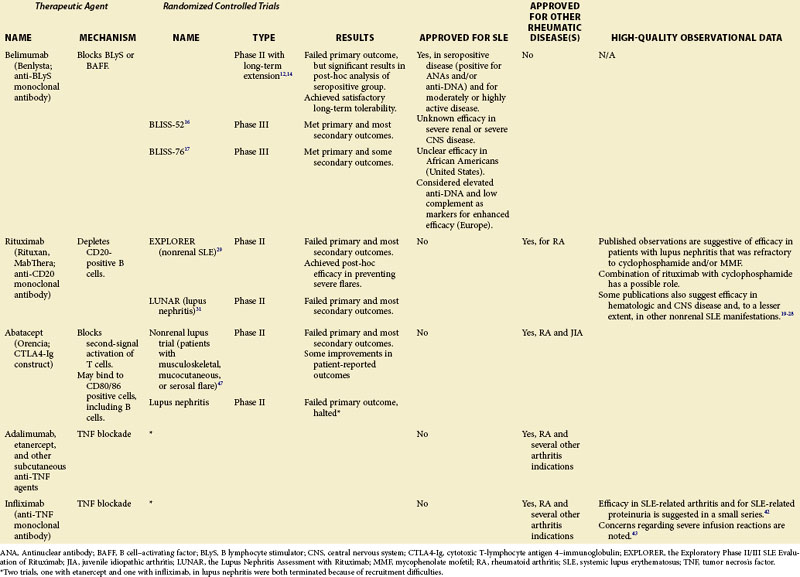

A number of therapeutic agents available to the clinician who is treating patients with SLE are reviewed in this chapter, including the newly approved biologic belimumab as well as several biologic medications that are not approved for the treatment of SLE, but whose off-label use is supported by some published observations or theoretical considerations or both. These data are summarized in Table 53-1. Agents currently in clinical development but not yet available are discussed separately in Chapter 56.

Belimumab

The development of belimumab was based on an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms leading to B-cell activation1–3 and the realization that some of the immune abnormalities in SLE might be reversed by the inhibition of the B-lymphocyte stimulator4 (BLyS); also known as the B cell–activating factor (BAFF), a member of the TNF-ligand family and a key survival cytokine for B cells.5 An overexpression of BLyS promotes the survival of B cells (including autoreactive B cells), whereas the inhibition of BLyS results in autoreactive B-cell apoptosis. Elevated circulating BLyS levels are common in SLE and correlate with increased SLE disease activity and elevated anti–double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody concentrations.6–9

Belimumab (Benlysta), formerly LymphoStat-B, is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds soluble human BLyS and inhibits its biologic activities.10,11 It is administered in the form of four-weekly infusions. In a phase II study of patients with active SLE who were receiving standard therapies, treatment with belimumab led to modest reductions in the number of circulating CD20+ B lymphocytes and significant reductions in anti-dsDNA antibody titers; in addition, safety and tolerability were good.12 Although the trial did not meet its prespecified primary endpoint, additional analyses determined that patients with either antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) of 1 : 80 or greater or anti-dsDNA antibodies of 30 IU/ml or greater had significantly reduced SLE disease activity and fewer flares with belimumab, compared with placebo. From a clinical perspective, focusing on such patients was quite logical, in that patients lacking both antibodies would not generally be considered typical SLE patients. It is also worth noting that from a clinical trials’ perspective, performing subanalyses on phase II data to determine the optimal design for phase III is perfectly legitimate.13

In a 5-year, open-label extension of the phase II study, improvement in SLE disease activity was sustained in the seropositive subset remaining on treatment, and rates of adverse events remained stable or decreased.14

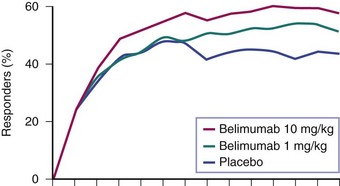

For a patient to be classified as a responder by SRI, he or she must have an improvement in the SLEDAI of at least 4 points, while simultaneously experiencing no worsening of the disease in other organ systems (defined as not having a new British Isles Lupus Assessment Group [BILAG] score of A and not having two new BILAG scores of B) or by physician judgment (defined as not having a worsening of the physician’s global assessment [PGA] by 0.3 or more).15 Both of these trials allowed for changes of glucocorticoid doses on the basis of the clinical course (i.e., increased doses in case of flare, decreased doses in stable situations) and, to a more limited degree, changes in other concomitant medications.

A 52-week randomized, controlled clinical trial with 867 patients—a study of Belimumab in Subjects with SLE (BLISS-52)—was conducted primarily in Asia, South America, and Eastern Europe. At several time points, the percentage of patients who achieved the SRI response was significantly greater for patients receiving belimumab, compared with placebo (Figure 53-1).16 This included the 52-week time point used for the primary outcome of the trial, at which time 44% of patients on placebo were SRI responders and 58% of those who were on belimumab 10 mg/kg (p = 0.0024). In addition, significant reductions in SLE disease activity, fewer flares, and reduced glucocorticoid use in patients on belimumab were observed, compared with placebo.

FIGURE 53-1 The effects of belimumab in active, seropositive systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).16 Patients were given fourweekly infusions of belimumab or placebo. Percentage responders at each time point were defined by the SLE Response Index (SRI), a compound of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG), and physician’s global assessment. The differences among patient groups were statistically significant at multiple time points, including at the 52-week assessment chosen as the primary outcome of the trial.

BLISS-76 was a 76-week randomized, controlled clinical trial with 819 patients conducted primarily in North America and Europe. Treatment continued through week 72 with the final evaluation at week 76. In this trial, the primary outcome was the SRI response at week 52, and it was again significantly greater for 10 mg/kg belimumab than for placebo (43% versus 34%, p = 0.017). However, in contrast to BLISS-52, the lower belimumab dose did not achieve a significant difference from placebo, and the differences at other time points were likewise not statistically significant. Other outcomes, such as the frequency of flare and the use of concomitant glucocorticoids, were also generally better for the belimumab-treated groups, but statistical significance was more variably achieved.17

Subsequent analyses of the pooled data from both trials revealed that the difference between belimumab and placebo was most notable in patients with additional evidence for immune activation in the form of anti-DNA antibodies and/or low complement, as well as in patients who were receiving glucocorticoids at baseline.18

1. In the trials, SLE was measured by complex indices (the SLEDAI and the BILAG) and assessed by a compound based on those indices (the SRI). These measurements are not realistic for clinical practice and, moreover, entail a significant amount of variability or noise. Therefore the noise possibly masked the effect of the intervention to some extent, and the true effect is, perhaps, more robust than it seems. In practice, physicians and patients need to have a very clear understanding, when initiating therapy, of what therapeutic goals are going to have to be achieved to motivate continued therapy.

2. Belimumab appears to be most effective in patients who have moderate- or high-clinical SLE activity, who have evidence for serologic immune activation, and who need glucocorticoid medications; each of these patient characteristics increases the likelihood of benefit. Consequently, it would seem sensible to consider belimumab in these types of patients at this time.

Rituximab

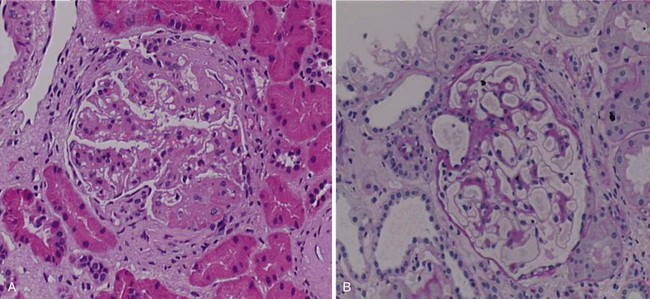

Rituximab (Rituxan, MabThera) is a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that was originally developed as a therapeutic agent for B-cell lymphoma in the 1990s. After its approval for use in this disease, it rapidly became one of the most widely used biologic agents worldwide, based on its ability to provide benefit for patients with low-grade non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas, a patient group for whom few other options are available. It has the ability to synergize with other antineoplastic therapies for the treatment of high-grade lymphoma and, perhaps most importantly for the clinician, it offers a relatively benign side-effect profile, considering the seriousness of the diseases under treatment. In the late 1990s, Dr. Jonathan Edwards in London suggested that rituximab might also benefit patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a suggestion that at the time was not at all intuitive, in that the role of B cells in RA pathogenesis was poorly defined. Despite that fact, subsequent large-scale, randomized clinical trials in RA clearly demonstrated that rituximab had important therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of that disease, and it was subsequently approved for use in patients who had failed anti-TNF agents. Largely based on these encouraging results, various groups of investigators began to explore the possibility of treating other autoimmune diseases with rituximab as well. Because SLE is characterized by a range of autoantibodies, some of which are clearly pathophysiologically important, considering the use of this B-cell agent in SLE was not illogical. Thus Leandro and others19 initially published data demonstrating important clinical improvements in a group of patients with moderate-to-severe and refractory SLE who were given a single course of rituximab in the dose approved for the treatment of lymphoma (four doses 375 mg/m2 at weekly intervals). In the author’s unit at the Karolinska University Hospital, a large number of patients were treated in this manner, and the results were reported in several publications. Specifically, an initial report of two cases demonstrated dramatic clinical improvements in patients with a prior manifest failure of treatment with cyclophosphamide (CyX)20 (Figure 53-2).20 Both patients suffered from lupus nephritis, and biopsies were taken before and after rituximab treatment in both cases, which demonstrated remarkable improvements in renal histologic findings. Later, a larger group of patients with refractory lupus nephritis demonstrated similar responses, all confirmed by biopsies.21 It should be noted that these patients were treated with the combination of rituximab in the previously referenced dose plus 500 mg CyX administered twice and glucocorticoids as intravenous boluses and/or a higher oral dose with subsequent tapering. In a separate report from this unit, patients were described with both renal and nonrenal lupus that had remained refractory to conventional immunosuppressive treatments and who were administered rituximab.22 After rituximab treatment, the vast majority of patients had improvements that were clinically meaningful and relatively long-lasting. The safety profile of rituximab appeared adequate throughout these uncontrolled observations. Additional groups of investigators also reported on the results of rituximab treatment in SLE. Among these reports are the dose-ranging studies in mild SLE by Looney and others,23 in which some improvements were observed; a large series of patients with lupus nephritis studied in Greece24; more follow-up on the large cohort of patients in London25; a large cohort of patients in France26,27; and other published case series that also supported these general impressions. In a recent metaanalysis, data on 188 cases were included.28

FIGURE 53-2 Effects of rituximab in a patient with refractory lupus nephritis. The patient, in whom a prior biopsy (not shown) revealed highly active membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, received six monthly infusions with cyclophosphamide (CyX) at 0.75 mg/m2. After this treatment, a repeat biopsy was performed and revealed ongoing highly active disease (panel A). On the basis of this finding, the patient was given a course of rituximab (four doses at 375 mg/m2) plus CyX (two doses at 500 mg) and methylprednisolone (two doses at 500 mg) over 4 weeks with no further therapy. Three months later, a third biopsy revealed almost complete resolution of the glomerular inflammation (previously unpublished biopsy images from this patient described in reference 18) (panel B). This patient has since remained in a renal remission for more than 8 years without further immunosuppressive therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree