Chapter 22 Overview and Clinical Presentation

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is considered the most clinically and serologically diverse autoimmune disease because it can affect almost any organ and display a broad spectrum of manifestations.1 It may manifest as a mild disease with skin or joint involvement only or may be severe, affecting vital organs such as the kidney, central nervous system (CNS), and heart. This is why SLE has been addressed as a constellation of different clinical variants, or better, as a galaxy,2 considering that clinical manifestations not only differ from patient to patient but also show considerable geographic and ethnic variation. This diversity is related to the role of genetic and environmental factors as well as abnormalities of the immune system that influence both susceptibility and clinical expression.3,4

History

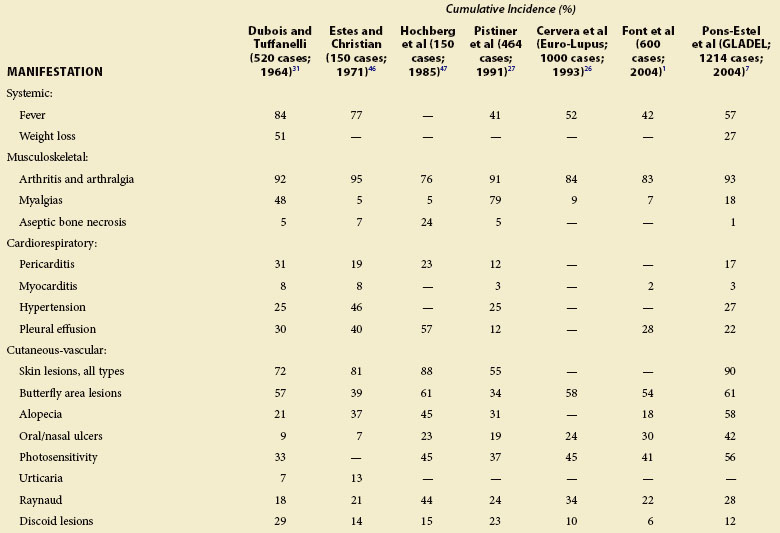

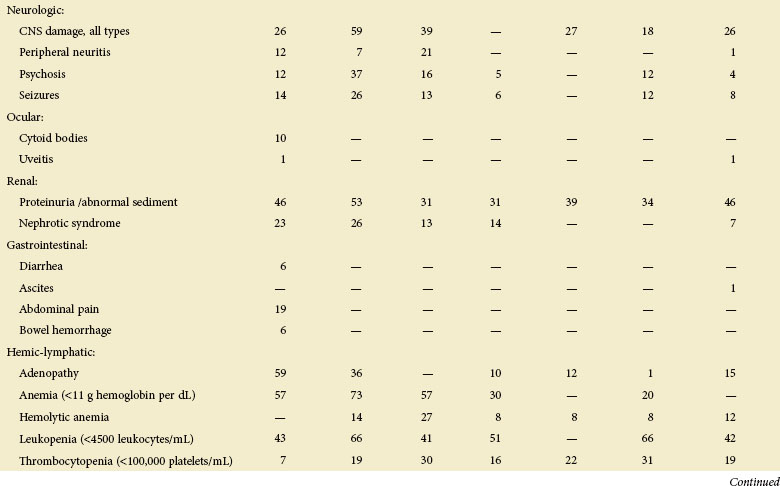

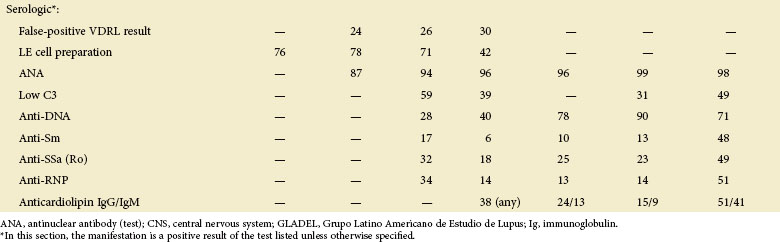

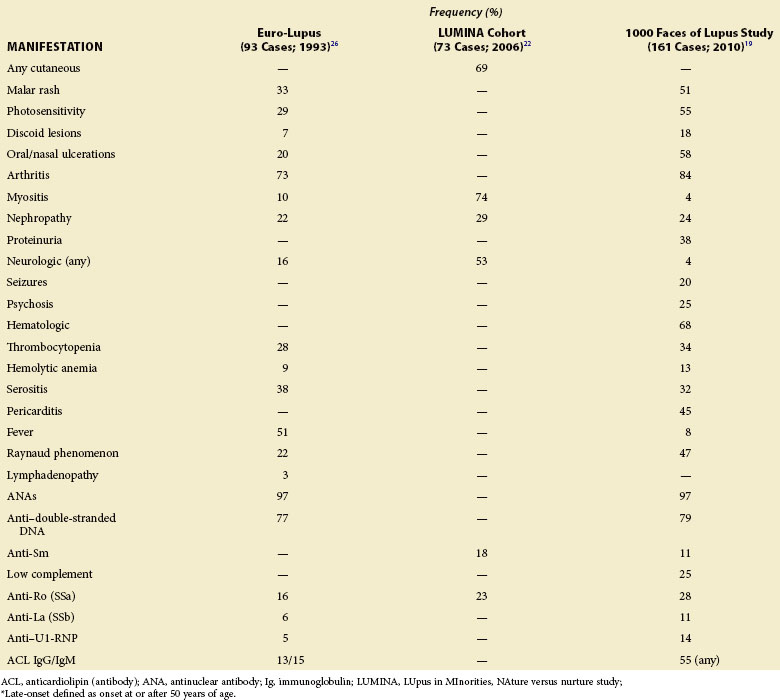

Considering the broad spectrum of clinical and immunologic manifestations displayed by patients with SLE, it is important to cover the items presented in Table 22-1, which reviews the cumulative incidence of clinical manifestations in several SLE cohorts.

Regardless of their age and gender, Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians tend to have more hematologic, serosal, neurologic, and renal manifestations and to accrue more damage and at a faster pace than Caucasians.5 Africans progress more commonly to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), show higher activity at diagnosis and in disease course, and are more commonly affected by discoid rash than Europeans (they present more frequently with malar rash and photosensitivity). Asian and Arab patients show higher frequency of renal disease and damage than Europeans.6 On the other hand, Hispanics are more heterogeneous in their disease manifestations, with their clinical profile depending on their African, European, or mestizo ethnicity.7 This heterogeneity reflects genetic, environmental, socioeconomic, and access to medical care differences.8

Chief Complaint

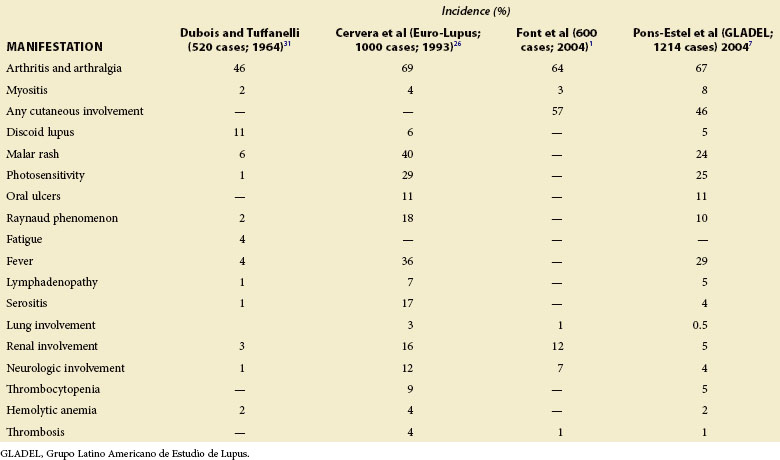

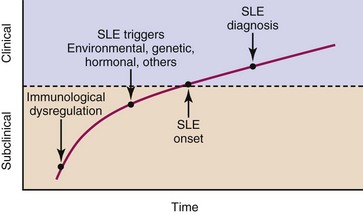

The presenting complaint varies in patients with SLE. Table 22-2 lists the manifestations noted at the diagnosis of SLE in several studies, and Figure 22-1 shows the preceding factors, onset, and progression of the disease.

In the LUpus in MInorities, NAture vs. Nurture (LUMINA) study’s multiethnic cohort, the most common initial manifestation of SLE was arthritis (34.5%), followed by photosensitivity (18.8%) and antinuclear antibody (ANA) positivity (14.2%).9 In addition, Cervera compared early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1000 patients and found that the majority of manifestations occurred more frequently during the first 5 years.10 It is useful to identify the initial SLE manifestations because the long-term prognosis differs with respect to them.11

One of the most challenging issues in attributing clinical manifestations to SLE is to define when the disease begins. The lag time between the onset of SLE and its diagnosis reported in major cohorts was almost 50 months before 1980, 28 months in the years 1980 to 1989, 15 months in the years 1990 to 1999, and 9 months after 2000.12 This difference results from the introduction of ANA testing and advances in the knowledge of autoimmune diseases over time.

Although currently there are no reliable clinical or serologic predictors that allow the identification of SLE at an early stage, there is evidence that at least one autoantibody (more frequently an ANA) is present during a mean time of 3.3 years before the diagnosis of SLE in 88% of patients.13

Mariz tested for ANAs in 918 healthy individuals and in 153 patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, and found positive results in 118 (13%) of the former group and in 138 (90%) of the latter group, with higher titers and distinctive patterns present in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases.14 When 40 of the ANA-positive healthy individuals were reevaluated after 3.6 to 5 years, all remained healthy and 73% continued testing ANA positive.

Variations in Clinical Presentation

Incomplete Lupus

It is common for rheumatologists to care for patients who are thought to have SLE but do not meet criteria. These patients are considered by some to have “incomplete,” “subclinical,” “incipient,” “possible,” “mild,” “latent,” or “variant” SLE.9,15 It is likely, however, that some of these cases are part of the disease spectrum.

In a multicenter European study involving 122 patients with incomplete lupus, SLE developed in 22 patients according to the ACR criteria in the first year, and in 3 additional patients within 3 years. These patients presented with cutaneous and musculoskeletal activity as well as leukopenia.16

Ganczarczyk followed 22 patients with latent lupus prospectively for at least 5 years and found that they differed from patients with SLE in the lack of renal and central nervous system involvement as well as the lower frequency of anti-DNA antibody and depressed complement levels.17 Seven patients (32%) eventually had SLE, and no predictive factors distinguished them from the 15 who did not.

In a Swedish study of 28 patients with incomplete lupus identified between 1981 and 1992, SLE developed in 16 patients (57%) in a median time of 5.3 years. Malar rash and anticardiolipin antibodies were predictors of SLE, and patients in whom the disease developed were more prone to organ damage.18

Late-Onset Lupus

Late-onset SLE, which has been defined as age of onset at or after 50 years, is an uncommon condition that occurs with a frequency of 12% to 18%.19 The less awareness of its occurrence, insidious onset, and fewer classic manifestations have led to a delay between the onset and diagnosis. Table 22-3 summarizes the main characteristics of patients with late-onset SLE in large studies.

Age is known to have an important effect on the clinical expression of the disease.20 Although it has been recognized that patients with late-onset SLE have lower levels of activity and less major organ involvement, other studies have identified increasing age as an independent factor for poor outcome in terms of damage accrual and mortality.5,20–23 Factors associated with age (i.e., comorbidities) may explain these findings, rather than true differences in disease phenotype.

Male Lupus

Data accumulated in the literature account for approximately 4% to 22% of male patients in lupus series, but up to 30% in studies considering familial aggregation. Lupus is 8 to 15 times more common in women at childbearing age than in age-matched men; before puberty this ratio is 2 : 1 to 6 : 1, and after menopause 3 : 1 to 8 : 1.24

In a cohort of 107 Latin American male patients with SLE, there was a higher prevalence of renal disease, vascular thrombosis, and anti-dsDNA antibodies, as well as a greater use of moderate to high doses of corticosteroids, in comparison with female patients.25 Other large studies have confirmed the finding of greater renal involvement in men.26–28 Furthermore, in the LUMINA study, men accrued damage early, predisposing them to accrue more damage subsequently.29,30 Additional clinical manifestations found to be more common among males with lupus include serositis, neurologic and cutaneous manifestations, hepatosplenomegaly, cardiovascular manifestations, fever and weight loss at onset, hypertension, and vasculitis.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree